Deconstruction Ahead: How Urban Highway Removal Is Changing Our

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of New Orleans Residential Parking Permit (Rpp) Zones

DELGADO CITY PARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE FAIR GROUNDS ZONE 17 RACE COURSE ZONE 12 CITY OF NEW ORLEANS RESIDENTIAL PARKING E L Y PERMIT (RPP) ZONES S 10 I ¨¦§ A ES N RPP Zones Boundary Descriptions: PL F A I N E Zone 1: Yellow (Coliseum Square) AD L E D St. Charles Avenue / Pontchartrain Expwy / S AV Mississippi River / Jackson Avenue A T V S Zone 2: Purple (French Quarter) D North Rampart Street / Esplanade Avenue / A Mississippi River / Iberville Street O R TU B LA Zone 3: Blue NE ZONE 11 South Claiborne Avenue / State Street / V AV Willow Street / Broadway Street A C N AN O AL Zone 4: Red (Upper Audubon) T S LL T St. Charles Avenue / Audubon Street / O Leake Avenue / Cherokee Street R R A 10 Zone 5: Orange (Garden District) C ¨¦§ . S St. Charles Avenue / Jackson Avenue / ZONE 2 Constance Street / Louisiana Avenue Zone 6: Pink (Newcomb Blvd/Maple Area) Willow Street / Tulane University / St. Charles Avenue / South Carrollton Avenue Zone 7: Brown (University) Willow Street / State Street / St. Charles Avenue / Calhoun Street / Loyola University ZONE 18 Zone 9: Gold (Touro Bouligny) ZONE 14 St. Charles Avenue / Louisiana Avenue / Magazine Street / Napoleon Avenue ZONE 3 AV Zone 10: Green (Nashville) NE St. Charles Avenue / Arabella Street / ZONE 6 OR Prytania Street / Exposition Blvd IB LA C Zone 11: Raspberry (Faubourg Marigny) S. TULANE St. Claude Avenue / Elysian Fields Avenue / UNIVERSITY ZONE 16 Mississippi River / Esplanade Avenue ZONE 15 Zone 12: White (Faubourg St. John) DeSaix Blvd / St. Bernard Avenue / LOYOLA N North Broad Street / Ursulines Avenue / R UNIVERSITY A Bell Street / Delgado Drive ZONE 7 P O E L Zone 13: Light Green (Elmwood) E AV ZONE 1 Westbank Expwy / Marr Avenue / O ES V General de Gaulle Drive / Florence Avenue / N L ZONE 4 R Donner Road A HA I V . -

Facing the Future in St. Bernard Parish, Louisian: Planning and Development

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-1984 Facing the Future in St. Bernard Parish, Louisian: Planning and Development Gregory L. Chase University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Chase, Gregory L., "Facing the Future in St. Bernard Parish, Louisian: Planning and Development" (1984). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1718. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1718 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACING THE FUTURE IN ST. BERNARD PARISH, LOUISIANA: PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies In The School of Urban and Regional Studies by Gregory L. Chase Bachelor of General Studies University of New Orleans, 1978 August 1984 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincere thanks to the members of my thesis committee, Dr. -

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with Asterisks (**) Are Able to Vaccinate 16-17 Year Olds

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with asterisks (**) are able to vaccinate 16-17 year olds. Updated at 4:00 PM All sites are able to vaccinate adults 18 and older. Visit www.vaccinefinder.org for a map of vaccine sites near you. Parish Facility Street Address City Website Phone Acadia ** Acadia St. Landry Hospital 810 S Broadway Street Church Point (337) 684-4262 Acadia Church Point Community Pharmacy 731 S Main Street Church Point http://www.communitypharmacyrx.com/ (337) 684-1911 Acadia Thrifty Way Pharmacy of Church Point 209 S Main Street Church Point (337) 684-5401 Acadia ** Dennis G. Walker Family Clinic 421 North Avenue F Crowley http://www.dgwfamilyclinic.com (337) 514-5065 Acadia ** Walgreens #10399 806 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia ** Walmart Pharmacy #310 - Crowley 729 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walmart.com/covidvaccine Acadia Biers Pharmacy 410 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-3023 Acadia Carmichael's Cashway Pharmacy - Crowley 1002 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-7200 Acadia Crowley Primary Care 1325 Wright Avenue Crowley (337) 783-4043 Acadia Gremillion's Drugstore 401 N Parkerson Crowley https://www.gremillionsdrugstore.com/ (337) 783-5755 Acadia SWLA CHS - Crowley 526 Crowley Rayne Highway Crowley https://www.swlahealth.org/crowley-la (337) 783-5519 Acadia Miller's Family Pharmacy 119 S 5th Street, Suite B Iota (337) 779-2214 Acadia ** Walgreens #09862 1204 The Boulevard Rayne https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia Rayne Medicine Shoppe 913 The Boulevard Rayne https://rayne.medicineshoppe.com/contact -

Final Staff Report

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Summary of Uptown and Carrollton Local Historic District Proposals: The Historic Preservation Study Committee Report of April 2016, recommended the creation of the Uptown Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by the Mississippi River, Lowerline Street, South Claiborne Avenue and Louisiana Avenue, and the creation of the Carrollton Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by Lowerline Street, the Mississippi River, the Jefferson Parish line, Earhart Boulevard, Vendome Place, Nashville Avenue and South Claiborne Avenue. These partial control districts would give the Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC) jurisdiction over demolition. Additionally, it would give the HDLC full control jurisdiction over all architectural elements visible from the public right-of-way for properties along Saint Charles Avenue between Jena Street and South Carrollton Avenue, and over properties along South Carrollton Avenue between the Mississippi River and Earhart Boulevard. Recommendation: The City Planning Commission staff recommends approval of the Carrollton and Uptown Local Historic Districts as proposed by the Study Committee. Consideration of the Study Committee Report: City Planning Commission Public Hearing: The CPC holds a public hearing at which the report and recommendation of the Study Committee are presented and the public is afforded an opportunity to consider them and comment. City Planning Commission’s recommendations to the City Council: Within 60 days after the public hearing, the City Planning Commission will consider the staff report and make recommendations to the Council. -

Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been

Geographies of New Orleans Fifty Years After Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been Richard Campanella Geographer, Tulane School of Architecture [email protected] Published in the New Orleans Picayune-Advocate, August 12, 2019, page 1. Fifty years ago this summer, reports from Washington D.C. reached New Orleans that John Volpe, secretary of the Department of Transportation under President Richard Nixon, had cancelled the Riverfront Expressway—the high-speed, elevated interstate slated for the French Quarter. The stunning news, about a wildly controversy plan that had divided the community for years, was met with elation by the city’s growing preservationist movement, and head-shaking disappointment by local leaders in both the public and private sectors. A half-century on, the cancellation and the original proposal invite speculation —part mental exercise, part cautionary tale—about what greater New Orleans might look like today had the Riverfront Expressway gone forward. And it very nearly did: conventional wisdom at the time saw the new infrastructure as an inevitable step toward progress, following the lead of many other waterfront cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. But first, a recap on how the New Orleans plan got to Volpe’s desk. Rendering from Robert Moses' Arterial Plan for New Orleans, 1946, page 11, courtesy collection of R. Campanella The initial concept for the Riverfront Expressway emerged from a post-World War II effort among state and city leaders to modernize New Orleans’ antiquated regional transportation system. Toward that end, the state Department of Highways hired the famous—many would say infamous—New York master planner Robert Moses, who along with Andrews & Clark Consulting Engineers, released in 1946 his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. -

General Parking

NINE MINUTES FROM PARKING POLICIES FOR GENERAL PARKING MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME There is no general parking for vehicles, • 1000 Poydras Street MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME RVs, buses and limousines for the • 522 S Rampart Street PASS HOLDERS National Championship Game. All lots The failure of any guests to obey the surrounding the Mercedes-Benz 10 MINUTES FROM instructions, directions or requests of Superdome will be pass lots only. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME event personnel, stadium signage or Information regarding additional • 1000 Perdido Street management’s rules and regulations parking near the Mercedes-Benz Additional Parking lots can be found may cause ejection from the event Superdome can be found below. at parking.com. parking lots at management’s discretion, and/or forfeiture and cancellation of the parking PREMIUM PARKING LOTS RV RESORTS pass, without compensation. FIVE MINUTES FROM FRENCH QUARTER RV RESORT MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME 10 MINUTES FROM TAILGATING • 1709 Poydras Street MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME Tailgating in Mercedes- Benz 500 N. Claiborne Avenue Superdome lots is prohibited for the NINE MINUTES FROM New Orleans, LA 70112 National Championship Game. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME Phone: 504.586.3000 • 400 Loyola Avenue Fax: 504.596.0555 TOWING SERVICE Email: [email protected] For towing services and assistance, 10 MINUTES FROM Website: fqrv.com please call 504-522-8123. Please raise MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME your car hood and/or notify an officer • 2123 Poydras Street THREE OAKS AND A PINE RV PARK at any lot entrance. • 400 S Rampart Street 15–20 MINUTES FROM • 415 O’Keefe Avenue MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME DROP-OFF AND 7500 Chef Menteur Highway • 334 O’Keefe Avenue PICK UP AREAS New Orleans, LA 70126 Guests can utilize the drop off and pick Additional parking lots can be found Phone: 504.779.5757 up area at the taxi drop off zone on at premiumparking.com. -

Department Name

Infrastructure & Operations Team Six Month Check-In City of New Orleans November 7, 2018 Capital Projects Administration City of New Orleans Gert Town Natatorium (Pre-Katrina) Gert Town Natatorium (New Facility) Gert Town Natatorium – Ribbon Cutting on 10/11/18 . Location: 3411 Broadway Street . Funding -- $7.9 million (Council District B) – FEMA -- $6.2 million . Project Team – Bonds -- $1.7 million – Grace Hebert (formerly HMS), Architects – Landis Construction, GC Gert Town Natatorium The project scope included construction of a new, 15,000 square foot natatorium with a 25-yard, 6-lane pool, ranging depths from 3.5’ to 10’-0”. City of New Orleans 3 Gert Town Police Station (NOPD District 2) -- Ribbon Cutting on 10/11/18 . Location: 3411 Broadway Street . Funding -- $8.3 million (Council District B) – FEMA -- $6.6 million . Project Team – Bonds -- $1.7 million – Concordia Architects – Kevin J. Smith Construction, GC Gert Town Police Station (NOPD 2nd District) The project scope included construction of a new, 2-story, 17,000 square foot police station with 1st & 2nd floor lobby areas, roll call room, conference room (that can be used for community meetings), men's and women's locker rooms, break room, exercise room and office spaces. City of New Orleans 5 Low Barrier Shelter – Ribbon Cutting on 9/18/2018 . Location: 1503 Gravier Street . Funding -- $2.6 million (Council District B) – City -- $1 million . Project Team – DDD -- $1 million – Other -- $600k – Mathes Brierre, Architects – K.J. Smith Construction, GC Low Barrier Shelter The project scope includes renovations at the 2nd floor of the old VA Hospital, Gravier St. -

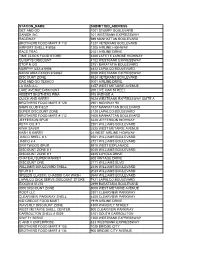

Station Name Submitted Address Get And

STATION_NAME SUBMITTED_ADDRESS GET AND GO 1001 STUMPF BOULEVARD DANISH INC 101 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY RACEWAY 989 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD BROTHERS FOOD MART # 113 1227 VETERANS BOULEVARD AIRPORT SHELL # 8058 1205 AIRLINE HIGHWAY RACE TRAC 2101 AIRLINE DRIVE TIME CLOCK FOOD STORE 4400 LAFITTE LAROSE HIGHWAY QUICKYS DISCOUNT 4102 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY STOP N GO 3751 BARATATIA BOULEVARD MURPHY USA # 6906 4822 LAPALCO BOULEVARD BARATARIA EXXON # 58087 5000 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY DISCOUNT ZONE 8824 VETERANS BOULEVARD GAS AND GO TEXACO 5001 AIRLINE DRIVE LA GAS LLC 4457 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE LAKE AVENUE DISCOUNT 200 LIVE OAK STREET HEBERT BROTHERS FINA 978 AVENUE A QUICK AND KARRY 9528 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY SUITE A BROTHERS FOOD MART # 128 2901 HIGHWAY 90 SAMS CLUB # 8221 1527 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD SUPER DISCOUNT ZONE 2120 LAPALCO BOULEVARD BROTHERS FOOD MART # 112 1600 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD JEFFERSON SPUR 3220 JEFFERSON HIGHWAY RETIF OIL # 1 2201 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD KWIK SAVER 2525 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE KASH N KARRY 22 WEST AIRLINE HIGHWAY JASCO SHELL # 3 3501 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD JASCO # 4 2721 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD DRIFTWOOD SPUR 8910 WEST ESPLANADE DISCOUNT ZONE # 1 4045 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD DISCOUNT ZONE # 1 2845 LOYOLA DRIVE CHATEAU SUPER MARKET 600 VINTAGE DRIVE DISCOUNT ONE 2111 WILLIAMS BLVD WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SHELL 2436 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SPUR # 1 2023 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SPEEDS CLASSIC CHASSIS CAR WASH 3940 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD LAPALCO QICK SERVE DISCOUNT STORE 7421 LAPALCO BOULEVARD EXXON # 51275 2699 BARATARIA BOULEVARD 8000 DISCOUNT ZONE 8000 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE -

Restoring Claiborne Avenue Alternatives for the Future of Claiborne Avenue

Restoring Claiborne Avenue Alternatives for the Future of Claiborne Avenue A Report to the Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition and Congress for the New Urbanism Prepared by Smart Mobility Inc. and Waggonner & Ball Architects 15 July 2010 CLAIBORNE CORRIDOR IMPROVEMENT COALITION The mission of the Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition is to plan and advocate for the transformation of the Claiborne Corridor into a healthy, vibrant boulevard that will not only serve as an anchor for the Corridor’s neighborhoods, but for the whole city of New Orleans. This report is the result of the efforts of the Coalition to gather information and inform the community about the alternatives for the Claiborne Avenue/I‐10 Corridor. The Coalition was formed by NEWCITY Neighborhood Partnerships, a coalition of developers, funders, neighborhood organizations, service providers, churches & faith‐ based groups, schools & universities, and government agencies focused on educational, economic, health, and housing development in the Tremé/Lafitte and Tulane/Gravier neighborhoods. The report has been prepared for the Coalition by the Congress for the New Urbanism, a national leader in promoting walkable, neighborhood‐based development as an alternative to sprawl, with assistance from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Ford Foundation. Members: Vaughn Fauria, NewCorp Inc., Co‐Chair, Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition (CCIC) Lisa Amoss, Broad Community Connections Bill Borah, Smart Growth for Louisiana Arianne Cousin, Urban Development Research Center Jack Davis, Smart Growth for Louisiana, Co‐Chair, CCIC Clifton James, Urban Development Research Center, Co‐Chair, CCIC Jim Kelly, Providence Community Housing/Catholic Charities, Co‐Chair, CCIC Nick Roosevelt, NEWCITY Neighborhood Partnership Daniel Samuels, Architect John Norquist, Congress for the New Urbanism Nora Beck, Congress for the New Urbanism Report Prepared for: Consultant Team: Lucy Gibson, P.E. -

May 2018 Transactions

MAY 2018 TRANSACTIONS OFFICE LEASES TENANT BUILDING SIZE CR BROKER(S) A1 Absolute Best Care Oakwood Corporate Center (Gretna, La.) 4,198 SF B. Sossaman (Landlord Rep) Arthur J. Gallagher Heritage Plaza (Metairie, La.) 12,765 SF J. Cohn (Tenant Rep) Automotive Experts LLC One Canal Place (New Orleans, La.) 2,926 SF A. Huseman (Landlord Rep) Bankers Insurance Company Interstate II (Metairie, La.) 5,015 SF C. Lewis (Landlord Rep) Betsy A. Fischer, LLC 3636 S I-10 Service Road (Metairie, La.) 1,814 SF C. Lewis (Landlord Rep) Bradley Murchison Energy Centre (New Orleans, La.) 13,225 SF M. Carrone (Landlord Rep) Branch Banking and Trust Company Causeway Plaza II (Metairie, La.) 8,273 SF J. Cohn (Landlord Rep) Delta Fiinancial Advisors, LLC One Shell Square (New Orleans, La.) 3,006 SF B. Sossaman (Landlord Rep) Doyle Land Services Inc. 400 Poydras Tower (New Orleans, La.) 11,101 SF H. Wren (Tenant Rep) ECAD 3939 N Causeway Blvd (Metairie, La.) 2,966 SF C. Lewis (Landlord Rep) Future Factory Louisiana, LLC Exchange Center (New Orleans, La.) 1,382 SF D. Whalen (Tenant Rep) Gregg May DDS 3939 N Causeway Blvd (Metairie, La.) 1,555 SF C. Lewis (Landlord Rep) Gulf South Development 3939 N Causeway Blvd (Metairie, La.) 475 SF C. Lewis (Landlord Rep) Gulf South Lithotripsy Causeway Plaza I (Metairie, La.) 964 SF J. Cohn (Landlord Rep) Lagniappe Travel Inc. Energy Centre (New Orleans, La.) 1,495 SF M. Carrone (Landlord Rep) Mississippi Valley Trade & Transport Council One Canal Place (New Orleans, La.) 895 SF A. Huseman (Landlord Rep) Patrick Dembrun CPA 3445 N Causeway Blvd (Metairie, La.) 1,539 SF J. -

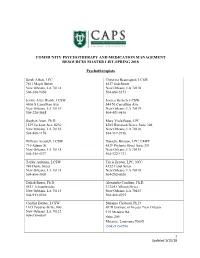

CAPS Spring 2018 Referral List.Pdf

COMMUNITY PSYCHOTHERAPY AND MEDICATION MANAGEMENT RESOURCES MASTER LIST-SPRING 2018 Psychotherapists Sarah Albert, LPC Christina Beauregard, LCSW 7611 Maple Street 8237 Oak Street New Orleans, LA 70118 New Orleans, LA 70118 504-300-9050 504-684-5373 Jennie Allee Walsh, LCSW Jessica Bertsch, LCSW 4616 S Carrollton Ave 644 N. Carrollton Ave. New Orleans, LA 70119 New Orleans, LA 70119 504-220-5865 504-453-9430 Stephen Anen, Ph.D. Mary Viola Bopp, LPC 1539 Jackson Ave. #230 8200 Hampson Street, Suite 306 New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70118 504-408-1170 504-717-2916 William Arendell, LCSW Danielle Brinson, LPC, LMFT 716 Adams St. 4829 Prytania Street Suite 201 New Orleans, LA 70118 New Orleans, LA 70115 504-358-0377 504-322-1721 Taylor Aultman, LCSW Tricia Brown, LPC, NCC 744 Dante Street 4322 Canal Street New Orleans, LA 70118 New Orleans, LA 70119 504-866-3003 504-252-0026 Daliah Bauer, Ph.D. Alexandra Casalino, Ph.D. 5521 Tchoupitoulas 3134A Calhoun Street New Orleans, LA 70115 New Orleans, LA 70125 504-913-0510 504-408-0795 Cynthia Baxter, LCSW Suzanne Chabaud, Ph.D. 1615 Poydras St Ste 900 OCD Institute of Greater New Orleans New Orleans, LA 70112 315 Metairie Rd 904-318-0567 Suite 200 Metairie, Louisiana 70005 (504) 915-9590 1 Updated 1/10/18 Mark Cheramie, LCSW Stacey Duarte, LPC-S 740 Dante Street 137 N. Clark St. New Orleans, LA 70118 New Orleans, Louisiana 70119 504-208-9554 504- 315-1037 Judy Barnes Cochran, Ph.D. Melissa Dufrene, PsyD 1426 Amelia Street 3520 General DeGaulle Dr. -

Commercial Real Estate + 504.301.1002 Commercial Real Estate

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE + 504.301.1002 COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE LARGE ST. CLAUDE COMMERCIAL ASSEMBLAGE 3014-32 St. Claude Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70117 LARGE ST. CLAUDE COMMERCIAL ASSEMBLAGE 3014-32 St. Claude Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70117 COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE DESCRIPTION A must-see, majestic property in the heart of St. Claude. Nestled in between some of the Bywater’s finest establishments, this gem, with over 150’ of commercial frontage, is ripe for a new life. Red’s Chinese, The Domino Lounge, Bywater Framing, N7, The Saturn Bar, The NOLA Bark Market, Galaxie Tacos, St. Germain, Sea Cave Arcade, The Get Down Lounge, and Junction are ALL located less than a block away. The backyard is enormous and forest-like. All buildings have most of their architectural antiques intact (original hardwood floors, fireplaces, windows, doors, etc) and all buildings qualify for state and federal historic tax credits. 3014 St. Claude: 3020-22 St. Claude: • 1,693 SF (bldg) • 2,694 SF (bldg) • 4,805 SF (land) • 14,821 SF (land) • 2 br/2 ba SFH • 2 br/1.5 ba each duplex • Central air, hardwood floors, great • Front and rear porch, rear shed, condition excess land, good condition 3024-26 St. Claude: 3030-32 St. Claude: • 2,000 SF (bldg) • 1,950 SF (bldg) • 3,990 SF (land) • 7,552 SF (land) • 2 br/1 ba & 1 br/1 ba raised duplex • 1 br/1 ba each raised duplex • Central air, front porch, rear shed, • Front and rear porch, rear shed, good condition excess land, great condition LAND SIZE: 31,168 SF ZONING: HMC-2/HMR-3 BLDG SIZE: 8,192 SF TOTAL # OF BLDGS: 4 EXCESS LAND: 22,831 SF PRICE: $1,900,000 DEMOGRAPHICS 2020 DEMOGRAPHICS 3 minutes 5 minutes 10 minutes ESTIMATED POPULATION 13,068 31,118 105,454 AVERAGE HH INCOME $54,142 $52,108 $52,357 COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE St.