PARENTS As Spiritual Guides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22Nd Day 433

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-FIFTH LEGISLATURE, REGULAR SESSION PROCEEDINGS TWENTY-SECOND DAY Ð THURSDAY, FEBRUARYi23, 2017 The house met at 10:06 a.m. and was called to order by the speaker. The roll of the house was called and a quorum was announced present (Recordi41). Present Ð Mr. Speaker(C); Allen; Alonzo; Alvarado; Anchia; Anderson, C.; Anderson, R.; AreÂvalo; Ashby; Bailes; Bell; Bernal; Biedermann; Blanco; Bohac; Bonnen, D.; Bonnen, G.; Burkett; Burns; Burrows; Button; Cain; Canales; Capriglione; Clardy; Coleman; Collier; Cook; Cortez; Cosper; Craddick; Cyrier; Dale; Darby; Davis, S.; Davis, Y.; Dean; Dutton; Elkins; Faircloth; Fallon; Flynn; Frank; Frullo; Geren; Giddings; Goldman; Gonzales; GonzaÂlez; Gooden; Guerra; Guillen; Gutierrez; Hefner; Hernandez; Herrero; Hinojosa; Holland; Howard; Huberty; Hunter; Isaac; Israel; Johnson, E.; Johnson, J.; Kacal; Keough; King, K.; King, P.; King, T.; Klick; Koop; Krause; Kuempel; Lambert; Landgraf; Lang; Larson; Laubenberg; Leach; Longoria; Lozano; Lucio; Martinez; Metcalf; Meyer; Miller; Minjarez; Moody; Morrison; MunÄoz; Murphy; Murr; Neave; NevaÂrez; Oliveira; Oliverson; Ortega; Paddie; Parker; Paul; Perez; Phelan; Phillips; Pickett; Price; Raney; Raymond; Reynolds; Rinaldi; Roberts; Rodriguez, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Romero; Rose; Sanford; Schaefer; Schofield; Schubert; Shaheen; Sheffield; Shine; Simmons; Springer; Stephenson; Stickland; Stucky; Swanson; Thierry; Thompson, E.; Tinderholt; Turner; Uresti; VanDeaver; Villalba; Vo; Walle; White; Wilson; Workman; Wray; Wu; Zedler; Zerwas. Absent, Excused Ð Gervin-Hawkins; Smithee; Thompson, S. Absent Ð Deshotel; Dukes; Farrar. The speaker recognized Representative Bailes who introduced Dalton Currie, associate pastor of evangelism and outreach, First Baptist Church, Coldspring, who offered the invocation as follows: Our dear heavenly Father, as we come to you today, we ask a hedge of protection around our state leaders. -

Still Drinking

Vol. 8 april2016 — issue 4 INSIDE: slow future - still drinking - line out: LUCA - priced outta b/cs - YOU’RE NOT PUNK & I’M TELLING EVERYONE - trauma Tuesday still poetry - Ask creepy horse - pedal pushing - QUITTING COFFEE - RICKSHAW HEART - record reviews concert calendar Priced outta b/cs I moved to College Station ten years ago. My family was somewhat unceremoni- ously kicked out of Seattle and needed somewhere to go. My wife found a job at Texas A&M so we loaded up the U-Haul and drove it 2000 979Represent is a local magazine miles in the July sun. We weren’t chased out of the for the discerning dirtbag. Emerald City because of crime or anything improper, we were chased out by the drastic increase in the cost of living and the continued stagnation of mid- Editorial bored dle class wages. We conducted a national search Kelly Minnis - Kevin Still for college towns with excellent schools to work at and communities attached that were inexpensive, low crime, and with excellent school systems. We got lucky when we landed in College Station. There Art Splendidness have been many times in recent years that we have Katie Killer - Wonko The Sane tried to move away but ultimately it did not come to fruition, most of the time because we’d say to our- Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us selves, “OK, where can we find a place in this new timOTHY danger - Mike e. downey - Jorge goyco - todd town that’s like here but not, you know, here?” and Hansen - chris Kirkpatrick - Jessica little - Amanda we could not find a satisfactory answer. -

Hree Sons, But

By:AARaymond H.R.ANo.A564 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, Pianist Bobbie Nelson has been playing music for 2 virtually her entire life, and today, after nearly eight decades as 3 a performer, she is continuing to enrich the proud musical legacy of 4 Texas; and 5 WHEREAS, Bobbie Nelson was born on New Year 's Day 1931 in 6 Abbott; her parents divorced early in her childhood, and she and her 7 younger brother, Willie, were raised by their grandparents, William 8 and Nancy Nelson, who instilled in both children a deep love of 9 music; at the age of five, she learned to play keyboards from her 10 grandmother, first on the family pump organ and later on a piano her 11 grandfather bought for $35; after her brother learned the guitar, 12 the siblings began performing gospel songs together at school 13 events and at the local Methodist church; and 14 WHEREAS, In her early teens, Ms.ANelson got her start as a 15 touring musician, playing piano on the revival circuit with a 16 traveling preacher; at 16, she married Bud Fletcher, who organized 17 and managed the Nelson siblings ' first band, Bud Fletcher and the 18 Texans; she and her husband became the parents of three sons, but 19 after their marriage ended, she lost custody of her children for a 20 time because the courts disapproved of her occupation of playing 21 music in honky-tonks; her career was put on hold as she fought to 22 reunite her family, though she was able to put her talents to use 23 after being hired as a demonstrator for the Hammond Organ Company; 24 following stints in Fort Worth and -

Willie Nelson the Troublemaker Mp3, Flac, Wma

Willie Nelson The Troublemaker mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Troublemaker Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1248 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1892 mb WMA version RAR size: 1554 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 108 Other Formats: AU AAC MP1 DMF WAV MMF AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Uncloudy Day 4:38 A2 When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder 2:46 A3 Whispering Hope 5:32 A4 There Is A Fountain 3:12 Will The Circle Be Unbroken A5 4:31 Written-By – A.P. Carter* The Troublemaker A6 2:50 Written-By – Bruce Belland, David Somerville In The Garden B1 4:07 Arranged By – C. Austin Miles B2 Where The Soul Never Dies 4:13 B3 Sweet Bye & Bye 2:39 B4 Shall We Gather 3:05 B5 Precious Memories 7:33 Credits Arranged By – Willie Nelson (tracks: A1 to A4, B2 to B5) Backing Vocals – Dee Moeller, Doug Sahm, Larry Gatlin, Sammi Smith Bass – Dan Spears* Drums – Paul English Fiddle – Doug Sahm Guitar – Larry Gatlin Lead Vocals, Guitar – Willie Nelson Organ – Jeff Gutcheon Pedal Steel Guitar, Dobro – James Clayton Day Piano – Bobbie Nelson Producer – Arif Mardin Written-By – Traditional (tracks: A1 to A4, B1 to B5) Notes Some copies carry a stickered label on rear stating "Final Mix by Mickey Raphael and Ben Tallent.", together with details of the Willie Nelson Fan Club. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Willie The Troublemaker (LP, S 81565 CBS S 81565 UK 1976 Nelson Album) Willie The Troublemaker (LP, Columbia, KC 34112 KC 34112 US 1976 Nelson Album, Promo) -

A Guide to the Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson

A Guide to the Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson 1974-2003 [Bulk Dates 1974-1988] Collection 103 Descriptive Summary Creator: Fischer, Jody Title: Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson Dates: 1974 – 2003 [Bulk Dates 1974-1988] Abstract: Jody Fischer’s collection of photographs, audio cassette tapes and VHS tapes relating to Willie Nelson are represented. The materials are arranged into the following series: Personal Papers, Ephemera, Posters, Photographs, Audio Cassette Tapes, Video Cassette Tapes, and Artifacts. Identification: Collection 103 Extent: 20 boxes plus oversize folders (13 linear feet) Language: English. Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, Special Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Biographical Sketch Jody Fischer was born December 21, 1949. During the 1970’s she lived in New York City, and was active with the music scene. She was a bit of a musician and writer herself. According to a 1991 Texas Monthly article, she started following Willie Nelson in the early 1970’s helping wherever she could. When he purchased the Pedernales Country Club in 1979, she was hired on as his personal secretary. Her job was to schedule studio time for Willie and his musician friends, assist Lana Nelson with charitable work, and generally assist in managing the property. She also had a small part in his movie, Red-Headed Stranger, which was filmed on the property. When Willie Nelson began the Farm Aid movement, Jody took calls coming in from famers and their families, and is often quoted as being a compassionate listener. She was very close to the extended Nelson family, as well as involved in diverse causes such as Farm Aid and Native American civil rights. -

A Preliminary Inventory of the Willie Nelson Recording Collection 1954

A Preliminary Inventory of the Willie Nelson Recording Collection 1954-2010 Collection 066 Descriptive Summary Creator: Artificial Collection Title: The Willie Nelson Recording Collection Dates: 1954-2010 Abstract: The Willie Nelson Recording Collection spans 1954-2010, chronicling the career of renowned Texas singer, songwriter, and bandleader. The collection contains 877 recordings, including LPs, 45 rpms, audio cassettes, compact discs, VHS cassettes, and DVDs. Identification: Collection 066 Extent: 33 boxes (13 linear feet) Language: English. Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, The Wittliff Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Scope and Contents Note The Willie Nelson Recording Collection spans 1954-2010, chronicling the career of renowned Texas singer, songwriter, and bandleader. The collection contains 877 recordings, including LPs, 45 rpms, audio cassettes, compact discs, VHS cassettes, and DVDs. Included in the collection are recordings under Nelson’s leadership as well as recordings on which he is a guest musician, producer, or songwriter. Highlights from the collection include Nelson’s first 45 rpm record released under his name, “No Place For Me” b/w “Lumberjack” (pictured above), numerous live recordings, studio demos, and deluxe-edition CDs with rare and previously unreleased material. Some of Nelson’s earliest recordings as a guest musician and songwriter are featured in the collection that represents the bulk of Nelson’s official discography. The collection is arranged chronologically by publication date. Not every recording is dated, and some are listed with an approximate date of release. Some recordings are listed by their original release date, not the date of production of that particular disc, cassette, etc. For example, The Troublemaker was originally released on LP in 1976. -

Columbia Union Visitor for 1967

, t„, 4.; is 154445 . 4 U M B I 4, tr•445 N 15 ;SEPTEMBER 21, 196L s so 0•,,,,,,, , -,. ,,. hues ad on a plane abuse ourselves. It 5nge ",,o4`, ,- % as a "hat God is not to be treated merely '..,,st: .,,,,. ; 015 Further. .,„ 05010 --- Q5 as a the tart vita, try ,dbie YOU Olt THOU? ses re,s,C,t, a:7e La' "Si it odais,Tketsr, • 5iliICl Ski duct ,`044,,, 4,0 and rhoO h at this question has See 4,0 „.. alu,sns,oin oi US OFFER The ieeinsI„isrg it lie•" i‘41, IC tW prayer is nut • with this hi e zVZ oven orn 55, us, • •040.. be. he entered alooty- 40'" 4 ft 04 05 441.4, t4 k5, :, 'is a. ton INDISPIENSAIBLEI N eui "The Good JaireReview"—Our General Church Paper A • „.„fina ..11 lot 000 0o. too,. \ Sao ' a-7.4 ' I .5, la" di' a„, • dr 04 ‘/%4 sa LOP 1.41 , 1 As SI Last Minute News Items PS"41 As We Go To Press... Nipourr WILMINGTON, DEL.--Members of the newly formed National Adventist Choral Society presented a 45-minute sacred concert Saturday night, September 9. The meeting, held in the I.O.O.F. hall, was part of a three-week series being conducted by Elder Pierson, President of the General Conference, and Elder Griffin, Pastor of the Wilmington Church. Francisco de Araujo is the director of the chorale. LA SIERRA, CALIF.--Elvin Benton, Religious Liberty Secretary of the Columbia Union Conference and a member of the Maryland Bar, attended the four-day convention of the Seventh-day Adventist Lawyers' Association held at La Sierra College, August 24 to 27. -

A Concert by Willie Nelson at Four Winds New Buffalo's Silver Creek Event Center Has Been Rescheduled for April 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A CONCERT BY WILLIE NELSON AT FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO’S SILVER CREEK EVENT CENTER HAS BEEN RESCHEDULED FOR APRIL 2021 Previously purchased tickets are valid for the rescheduled concert NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – June 24, 2020 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi’s Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce that the concert by Willie Nelson at Four Winds New Buffalo’s Silver Creek® Event Center has been rescheduled for Friday, April 23, 2021, at 8 p.m. Ticket prices for the show range from $99 to $179, plus applicable fees, and can be purchased online at www.fourwindscasino.com. Previously purchased tickets are valid for the rescheduled concert, and for those guests who are unable to attend, refunds will be available at the point of purchase. Hotel rooms are available on the night of the concert and can be purchased with event tickets. With a six-decade career, Willie Nelson has earned every conceivable award as a musician and amassed reputable credentials as an author, actor, and activist. He continues to thrive as a relevant and progressive musical and cultural force. In recent years, he has delivered more than a dozen new albums, released a Top 10 New York Times’ bestsellers book, again headlined Farm Aid, an event he co-founded in 1985, and was honored by the Library of Congress with their Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. He has also received his 5th degree black belt in Gong Kwon Yu Sul, headlined the annual Luck Reunion food and music festival during SXSW, launched his cannabis companies “Willie’s Reserve” and “Willie’s Remedy,” and graced the covers of Rolling Stone and AARP The Magazine. -

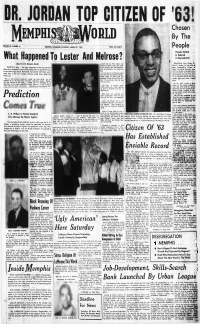

Prediction Tling up the Stars from Memphis

ï Chosen Memphi By The « i < VOLUME 32, NUMBER 41 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, MARCH 21, 1964 PRICE TEN CENTS Popular Dentist Is Selected In Citywide Poll v: ■ r? Memphians have chosen Dr. (Special to the Memphis World) another beef too They believe the Sas Lester ace. Richard Jones, lost some .* John E. Jordan for the title of NASHVILLE, Tenn. - So, what happened to the two hot-shot of his stamina and determination Most Outstanding Citizen of teams from Memphis? Experts had picked Lester to go all the way after he protested a foul called on 1963. The North Memphis den him. in the State High School Basketball Tournament and there were tist, civic leader and well-known In the case of the defeated Mel more than a few who thought Melrose would have made the tennis player moved to the front finals, loo. rose five, their star. Robert (Bobby) Smith, pulled up lame again but of the Memphis World poll three, managed to limp through the con weeks ago and never looked But. by now you know Lester got turned the trick, 59-58. In the test. It was obvious that he was knocked off in the semi-finals by other semi-final contest Melrose back. not up to par the tiny margin of one point. A trailed Pearl of Nashville by 20 He was given a total of 20,740 newcomer to the state basketball points, losing by a score of 63-43. And, there is another angle. points by his ardent supporters, scene, Riverside from Cattanooga, Memphians In the stands of Ten- "I»» « ' »? i There's some pretty good coaching more titan three times the number up here in Nashville and over at received by the first runnerup, Mrs. -

Arlingtongton APRIL 2014 Connectionconnection

TheThe Inside Senior Living ArlinArlingtongton APRIL 2014 ConnectionConnection Sara Melendez enjoys a moment in boot camp class, which takes place at the Walter Reed Senior Center, in Arlington. /The Connection The Veronica Bruno Veronica ArlinArlingtongton Connection Photo by Photo www.ConnectionNewspapers.comLocal Media Connection LLC onlineArlington at www.connectionnewspapers.com Connection ❖ Senior Living April 2014 ❖ 1 ArtFest SeniorSenior LivingLiving News, Page 2 Sports page 13 ❖ Classified, page 14 Classified, ❖ Entertainment, page 10 Fifteen Candidates For Congress JeanJean MooreMoore andand MegMeg MackenzieMackenzie withwith News, Page 3 Kristi Provasnik, standing, with art on exhibit as part of the 12th annual ArtFest Week at Fort C.F. Smith Park. Arlington’s Frothy Past News, Page 3 Helping Ex-Offenders Adjust News, Page 3 Photo by Keith Waters/Kx Photography online at www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.comApril 2-8, 2014 Arlington Connection ❖ April 2-8, 2014 ❖ 1 News ArtFest The 12th annual ArtFest Week is a week-long celebra- tion of visual art through April 4 at Fort C.F. Smith Park. Rusty Lynn (left) and Dennis Crayon, members of the Arlington Artists Alliance, with their art- work. Photos by Keith Waters Kx Photography Some of the artwork on exhibit through April 4. Fire Victims Special Election Identified The victims of a March 15 fire on South Next Tuesday Langley Street have been identified by the A special election to fill the County medical examiner. Firefighters found Board seat vacated by Chris Yvonne Barrie, 73, and Bobbie Nelson Zimmerman — for his unexpired term Goins, 77, dead in a second floor bedroom. to end Dec. -

463-6666 [email protected] Martin, Dale

Martin, Dale – Matthews, Sherry 151 Dale Martin, Music Writer Mas Distributors • Houston Masterpiece Mastering P.O. Box 311200, New Braunfels, TX 78131 819 Hogan, Houston, TX 77009 P.O. Box 2130 (830) 626-3424; Fax (830) 626-0825 (713) 228-7773 Wimberley, TX 78676-2130 [email protected] Matias Ramirez, Owner (512) 842-1431; Fax (512) 842-1431 [email protected] Michael Martin Mason Country Opry at the Odeon Theater www.masterpiecemastering.com P.O. Box 10662, Austin, TX 78766-1662 1701 South Bridge Street, Brady, TX 76825-7031 Billy Stull (512) 454-1135; (512) 462-2219; Fax (512) 454-5483 (325) 597-1895; (325) 597-2119; Fax (325) 597-0515 Mastering • Audio engineers [email protected] Compact disc manufacturers • Record producers Martin Professional, Inc. Tracy Pitcox, Producer National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences 7120 Rufe Snow Drive, Bldg. 106, Suite 303 Established: 1997 North Richland Hills, TX 76148 Mason Studio Established in beautiful Wimberley TX in 1997, the (817) 577-8404; (800) 200-1210; Fax (817) 577-8604 216 Forest Drive, Lake Jackson, TX 77566 tuned mastering laboratory now features an incredible Jeff Dougherty, Regional Sales Manager (979) 297-8924; [email protected] custom Analog Mastering System designed by Rodney Mason, Owner legendary audio designer Rupert Neve and conceived Narciso Martinez Cultural by veteran mastering engineer Billy Stull. This System Masquerade Entertainment dubbed Masterpiece is produced and marketed Arts Center 2186 Jackson Keller, Suite 412, San Antonio, TX 78213 worldwide by Legendary Audio P.O. Box 471 (210) 377-3535; Fax (210) 342-2568 www.legendaryaudio.com. Masterpiece empowers the San Benito, TX 78586 Ernest Calderon, Coordinator audio engineer to enhance, restructure, or repair stereo (956) 361-0110; (956) 425-9552; Fax (956) 361-0767 audio masters-digital or analog. -

PACAD280-ALL ACCESS/Issue 6

Unless you’ve been living under a manhole cover for the past year, you know about the spectacular success of singer/pianist Norah Jones. Come Away With Me , her 2002 debut album, won eight GRAMMY ® awards and has sold more than nine mil - lion copies—an astonishing feat for any new artist, let alone “With a really popular cover one whose stylistic hallmark is quiet understatement. song, you want to respect the person who did it, or the person Jones’ success proves that the world still hungers for who wrote it. I really do respect strong, simple songs, performed with honesty and taste. these songs, otherwise I wouldn’t sing them!” Norah spoke to us from a cavernous rehearsal hall in Florida, where she and her band were preparing to embark on their sum - mer tour. She talked candidly about her music and gave us an update on her most important project: the breathlessly awaited fol - Norlowa-up to Come Awh ay With Me. COME AWAY WITH Jones You’ve spoken often about the singers you admire. But which piano play - ers are closest to your heart? Ahmad Jamal and Oscar Peterson are two of my favorite jazz people. They swing in very different ways. Like, Oscar Peterson is just so swingin’! That sounds corny—“swingin’”— but he really does swing so hard. And Jamal always had these cool arrangements. But Bill Evans is probably my very favorite jazz player— he’s so unique, and his touch is so lyrical and beautiful. I was a big Bill Evans fan all through high school.