A Satire, Not a Sermon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kicking Off with Comedy Central's Roast of Rob Lowe

Media Release: Tuesday August 23, 2016 Get ready for a feast of Roasts on Foxtel Kicking off with Comedy Central’s Roast of Rob Lowe Tuesday September 6 at 8.30pm Express from the US on The Comedy Channel Hollywood heartthrob Rob Lowe is treated with his very own special Roast – and considering the skeletons in Lowe's closet, which include struggles with alcohol and an affair with Princess Stephanie of Monaco – the Roasters should have no problem finding topics to poke fun at. Comedy Central’s Roast of Rob Lowe will premiere Tuesday September 6 at 8.30pm Express from the US on The Comedy Channel. Known for his roles in St Elmo’s Fire, Wayne’s World, the Austin Powers franchise, The West Wing, Brothers & Sisters, Parks & Recreation, The Grinder and many, many more – Lowe has been a handsome fixture of our small and silver screens since the early 1980s. Get ready for Lowe’s dirty laundry to be aired when the Roasters spill the beans on his movie star lifestyle and brat pack antics. Comedy Central’s Roast of Rob Lowe will assemble a dais of comedians and celebrities, along with Roast Master David Spade (Saturday Night Live, Joe Dirt, Just Shoot Me!, Rules of Engagement), to take down the ageless sex symbol one burn at a time. The first round of Roasters confirmed include one of the UK's most distinctive comedians Jimmy Carr, Saturday Night Live’s Pete Davidson, actress and Lowe’s co- star Bo Derek, former NFL quarterback Peyton Manning, comedic actor Rob Riggle, and Roast alumni Jeff Ross. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Writing the Global: the Scottish Enlightenment As Literary Practice

Writing the Global: The Scottish Enlightenment as Literary Practice Yusuke Wakazawa PhD University of York English and Related Literature September 2018 2 Abstract This thesis presents the Scottish Enlightenment as a literary practice in which Scottish thinkers deploy diverse forms of writing---for example, philosophical treatise, essay, autobiography, letter, journal, and history---to shape their ideas and interact with readers. After the unsuccessful publication of A Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40), David Hume turns to write essays on moral philosophy, politics and commerce, and criticism. I argue that other representatives of the Scottish Enlightenment such as Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, and William Robertson also display a comparable attention to the choice and use of literary forms. I read the works of the Scottish Enlightenment as texts of eighteenth-century literature rather than a context for that literature. Since I argue that literary culture is an essential component of the Scottish Enlightenment, I include James Boswell and Tobias Smollett as its members. In diverse literary forms, Scottish writers refer to geographical difference, and imagine the globe as heterogenous and interconnected. These writers do not treat geography as a distinctive field of inquiry. Instead, geographical reference is a feature of diverse scholarly genres. I suggest that literary experiments in the Scottish Enlightenment can be read as responding to the circulation of information, people, and things beyond Europe. Scottish writers are interested in the diversity of human beings, and pay attention to the process through which different groups of people in distant regions encounter each other and exchange their sentiments as well as products. -

Comedy Central Roast of Justin Bieber Tuesday March 31 at 8.30Pm First on the Comedy Channel Express from the US

Media Release: Wednesday March 11, 2015 Comedy Central Roast of Justin Bieber Tuesday March 31 at 8.30pm first on The Comedy Channel Express from the US Hosted by Roast Master Kevin Hart, the Comedy Central Roast of Justin Bieber assembles a wide range of pop culture voices to hold one of the world's biggest teen idols over an open flame. The 20-year-old pop star has accepted the challenge to be roasted with ease and in a happy coincidence for audiences the event will fall on his 21st birthday. The Roast will be "no holds barred" and everything and anything is fair game. Actor and comedian Kevin Hart (Real Husbands of Hollywood) has been named the Roast Master and will be joined by Roast regular Jeffrey Ross – who is fast becoming Bieber’s worst nightmare. Comedian Hannibal Buress (Broad City), actor and stand up Chris D’Elia, rap royalty Snoop Dogg, actress Natasha Leggero, hip hop artist Ludacris, basketball legend Shaquille O’Neal, and controversial television personality Martha Stewart will also be stepping up onto the dais with Justin, with more names to be announced soon. Bieber, who is no stranger to being mocked and regularly cops flack in mainstream media like Saturday Night Live and on social media, is the first musician to get a roast since Flavor Flav had verbal shots fired at him in 2007. The most recent Comedy Central Roast was with James Franco who was skewered and burned in 2013. Whether you’re a diehard Belieber or not his biggest fan, you won’t want to miss this 90 minute special premiering on Foxtel’s The Comedy Channel Tuesday March 31 at 8.30pm Express from the US. -

Constructing British Identity : Tobias Smollett and His Travels Through France and Italy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2011 Constructing British identity : Tobias Smollett and his Travels through France and Italy Michael Anthony Skaggs 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Skaggs, Michael Anthony 1987-, "Constructing British identity : Tobias Smollett and his Travels through France and Italy" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1336. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1336 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTING BRITISH IDENTITY: TOBIAS SMOLLETT AND HIS TRA VELS THROUGH FRANCE AND ITALY By Michael Anthony Skaggs B.A., Indiana University, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY August 2011 Copyright 2011 by Michael Anthony Skaggs All rights reserved I j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j J CONSTRUCTING BRITISH IDENTITY: TOBIAS SMOLLETT AND HIS TRAVELS THROUGH FRANCE AND ITALY By Michael Anthony Skaggs B.A., Indiana University, 2005 A Thesis Approved on June 13, 2011 By the following Thesis Committee: John McLeod, Ph.D. -

Lisa Lampanelli

DVD | CD | DMD Lisa Lampanelli Long Live The Queen x 2 “Lisa Lampanelli says dreadful and appalling things for a living.… She is a cartoon of unsuppressed hatreds.… She’s SELECTIONS Standup Show (70 minutes) also as foul-mouthed as a Marine. HOMETOWN The Makeup F**k Up People love her for it. Like her idol, Don Trumbull, CT The Gorilla Joke Rickles, Lampanelli has elevated— The entire 70-minute show with probably the wrong verb—insult and DIRECTOR American Sign Language (ASL) shock to its own kind of comic art.” Dave Higby —Washington Post, January 24, 2009 PRODUCERS = Lisa Lampanelli, aka The Queen of Eileen Bernstein Mean, hilariously insults everyone and Dave Higby DISCOGRAPHY anyone on Long Live The Queen, spun FILE UNDER Dirty Girl (CD: 2-43271; DVD: 2-38711) Comedy (PA) off from her first HBO comedy special. Take It Like A Man (CD: 2-49441; Coming off two hit albums, sold-out gigs RADIO FORMAT DVD: 2-38644) (PA) at Radio City Music Hall and Carnegie Comedy Hall, appearances with Howard Stern, ON THE WEB and shockingly positive press (New York wbrnashville.com Times: “Fearlessly Foul, And On The insultcomic.com Verge Of Respectability”), Lampanelli is myspace.com/lisalampanelli the hottest female comedian in America. STREET DATE 3/31/09 I TELEVISION: Long Live The Queen debuted January 31 on HBO, with multiple airings to follow into March. I RECENT SUCCESS: 2007’s Dirty Girl was Grammy® nominated for Best Comedy Album and went Top 10 on the Comedy chart. The CD and DVD of her 2005 Comedy Central special “Take It Like A Man” peaked at #6 Comedy. -

Final Draft of Dissertation

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Victorian Talk: Human Media and Literary Writing in the Age of Mass Print Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3kb3d4xc Author Wong, Amy Ruei Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Victorian Talk: Human Media and Literary Writing in the Age of Mass Print A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Amy Ruei Wong 2015 © Copyright by Amy Ruei Wong 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Victorian Talk: Human Media and Literary Writing in the Age of Mass Print by Amy Ruei Wong Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Jonathan H. Grossman, Co-Chair Professor Joseph E. Bristow, Co-Chair “Victorian Talk: Human Media and Literary Writing in the Age of Mass Print” investigates a mid- to late-Victorian interest in the literary achievements of quotidian forms of talk such as gossip, town talk, idle talk, chatter, and chitchat. I argue that such forms of talk became inseparable from the culture of mass print that had fully emerged by the 1860s. For some, such as Oscar Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, this interdependence between everyday oral culture and “cheap literature” was “destroy[ing] beauty, grace, style, dignity, and the art of conversation,” but for many others, print’s expanded reach was also transforming talk into a far more powerful “media.” Specifically, talk seemed to take on some aspects of print’s capacity to float free from the bodies of individual speakers and endlessly reproduce across previously unimaginable expanses. -

Romance Tradition in Eighteenth-Century Fiction : a Study of Smollett

THE ROMANCE TRADITION IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FICTION: A STUDY OF SMOLLETT By MICHAEL W. RAYMOND COUNCIL OF A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA FOR THE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 197^ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express heartfelt appreciation to a few of the various multitude who provided incalculable tangible and intangible assistance in bringing this quest to an ordered resolution. Professors Aubrey L. Williams and D. A. Bonneville were most generous, courteous, and dexterous in their assist- ance and encouragement. Their willing contributions in the closing stages of the journey made it less full of "toil and danger" and less "thorny and troublesome." My wife, Judith, was ever present. At once heroine, guide, and Sancho Panza, she bore my short-lived triumphs and enduring despair. She did the work, but I am most grate- ful that she came to understand what the quest meant and what it meant to me. No flights of soaring imagination or extravagant rhetoric can describe adequately my gratitude to Professor Melvyn New. He represents the objective and the signifi- cance of the quest. He always has been the complete scholar and teacher. His contributions to this work have been un- tiring and infinite. More important to me, however, has been and is Professor New's personal example. He embodies the ideal combination of scholar and teacher. Professor Melvyn New shows that the quest for this ideal can be and should be attempted and accomplished. TABLE OE CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ±±± ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 NOTES 15 CHAPTER 1 15 I. -

Sacramental Woes and Theological Anxiety in Medieval Representations of Marriage

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Elizabeth Churchill University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Churchill, Elizabeth, "When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2229. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Abstract This dissertation traces the long, winding, and problematic road along which marriage became a sacrament of the Church. In so doing, it identifies several key problems with marriage’s ability to fulfill the sacramental criteria laid out in Peter Lombard’s Sentences: that a sacrament must signify a specific form of divine grace, and that it must directly bring about the grace that it signifies. While, on the basis of Ephesians 5, theologians had no problem identifying the symbolic power of marriage with the spiritual union of Christ and the Church, they never fully succeeded in locating a form of effective grace, placing immense stress upon marriage’s status as a signifier. As a result, theologians and canonists found themselves unable to deal with several social aspects of marriage that threatened this symbolic capacity, namely concubinage and the remarriage of widows and widowers. -

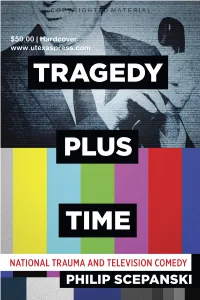

Hardcover C O P Y R I G H T E D M a T E R I a L

C O P Y R I G H T E D M A T E R I A L $50.00 | Hardcover www.utexaspress.com C O P Y R I G H T E D M A T E R I A L tragedy plus time MAY NOT BE COPIED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED C O P Y R I G H T E D M A T E R I A L MAY NOT BE COPIED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED C O P Y R I G H T E D M A T E R I A L National Trauma TRAGEDY PLUS TIME and Television Comedy philip scepanski university of texas press Austin MAY NOT BE COPIED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED C O P Y R I G H T E D M A T E R I A L Copyright © 2021 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2021 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713-7819 utpress.utexas.edu/rp-form The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48- 1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Scepanski, Philip, author. Title: Tragedy plus time : national trauma and television comedy / Philip Scepanski. Other titles: Tragedy + time : national trauma and television comedy Description: First edition. | Austin : University of Texas Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020032962 ISBN 978-1-4773-2254-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-4773-2255-0 (library ebook) ISBN 978-1-4773-2256-7 (non-library ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Television comedies—Social aspects—United States. -

The Cover Design of the Penguin English Library

The Cover Design of the Penguin English Library The Cover as a Paratext and as a Binding Factor in Canon Formation Jody Hunck S4056507 MA Thesis English Literature First reader: dr. Chris Louttit Second reader: dr. Dennis Kersten Penguin Pie by Mary Harvey Sing a song of sixpence A pocket full of dough Four and twenty Penguins Will make your business go! Since the Penguins came along The public has commenced To buy (instead of borrow) books And all for twenty cents The Lanes are in their counting house Totting up the gold While gloomy book trade prophets Announce it leaves them cold! From coast to coast the dealers Were wondering ‘if it paid’ When DOWN came the Penguins And snapped up the trade. (Quill & Quire, Toronto, May 1938) SAMENVATTING Het kaftontwerp van de Penguin English Library, een serie van honderd Engelse literaire werken gepubliceerd in 2012, heeft een bijzonder effect op de lezer. De kaft heeft twee verschillende functies. Ten eerste geeft het de lezer een idee van wat er in de kaft gevonden kan worden door het verhaal van de roman terug te laten komen in de kleur van de kaft en de gebruikte illustraties. De kaft zorgt er dus voor dat de lezer een idee krijgt van wat voor soort roman hij oppakt. Daarnaast zorgt de kaft ervoor dat de lezer de honderd boeken herkent als deel van een samenhangende serie. Deze honderd boeken zijn honderd werken waarvan uitgever Penguin vindt dat iedere fanatieke lezer ze gelezen moet hebben, maar deze romans hebben niet per se veel gemeen. -

THE ECCENTRICS of TOBIAS SMOLLETT's NOVELS Lajor

THE ECCENTRICS OF TOBIAS SMOLLETT'S NOVELS APPROVED» lajor Professor (d- Minor Profassor Director of the^ Department of ing'l'iah' Dean of the Graduate School THE ECCENTRICS OP TOBIAS SMOLLETT'S NOVELS THESIS O "> 1^""^ ^ Presented td""tht@ Graduate Council of the North Texas Stat® College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Qlenn E. Shookley, B. A, Denton, Texas August, 1961 TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Pag@ 1. SMOLLETT'S HKROSS ..... X II. SMOLLETT'S HBROINBS 20 III. SMOLLETT'S ECCENTRICS g8 General Observations The Important Sccantrlcg IV. SOUK CSS OF SMOLUSTT'SJ BCCEIJTRICS. ....... 73 ¥. CONCLUSION. ........... gg BIBLIOGRAPHY # 99 ill CHAPTER 2 SMOLLETT'S H£RGK5 fhe vitality and richness of Smollett's novels emanate not from his protagonist® or the picaresque plots contained therein but from the great variety of eooentrlos who populate the pages of the books. fhey are the .lole de vivre of Smollett's readers and prove to be both fine entertainment and objects deserving examination# Although the emphasis of this research lies In uncovering the prototypes of Smollett's eooentrlos, the method of characterization, and the author's techniques in transferring them to the pages of the novels, the analyst must consider the protagonists of the novels. Kven though these principal figures are not actually eccentrics, they are the only serviceable threads which hold together the multiple and unrelated episodes, plots, subplots, and character© in his novels. The major eccentrics are always linked with the hero and, like the hero, usually turn up in each of Smollett's novels, possessing new names but having essentially the same sets of character traits# Hence, the male protagonists are first considered here, to give the reader a useful image of Smollett's fictional milieu before they encounter the eccen- tric s • 2 Critics who class Smollett as a picaresque novelist and his "heroes" as pioaroa do 30 without defining the terms and without realizing that their use of them is quite often a® inaccurate as it is handy.