“Beach People” Take Flight: Inventing the Airplane and Modernizing the Outer Banks of North Carolina, 1900-1932 Bryan E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Index Books

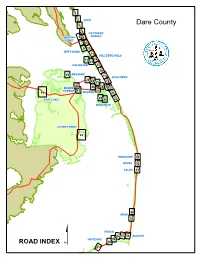

1 2 DUCK 3 Dare County 4 SOUTHERN SHORES MARTINS 5 6 POINT 7 8 9 10 KITTY HAWK 11 KILL DEVIL HILLS 14 12 13 COLINGTON 15 16 45 MASHOES 17 NAGS HEAD 23 24 25 18 42 MANNS 26 28 19 20 HARBOR 43 27 46 MANTEO 21 EAST LAKE 29 30 22 WANCHESE STUMPY POINT 44 RODANTHE 31 WAVES 32 SALVO 33 34 AVON 35 FRISCO 38 37 36 BUXTON HATTERAS 39 ROAD INDEX $ 40 41 N BAUM TRL S BAUM TRL DUCK RD - NC 12 A B STATIONBAY DRIVE MARTIN LANE VIREO WAY QUAIL WAY GANNET WAXWING LANE LANE WAXWING GANNET COVE COURT HERON LN BLUE RUDDY DUCK LN PELICAN WAY TERNLN ROYAL LANE BUNTING SHEARWATER WAY BUNTING BUNTINGLN WAY C D SKIMMER WAY WAY SKIMMER OYSTER CATCHER LN SANDPIPERCOVE OCEAN PINES DRIVE FLIGHT DR OCEAN BAY BLVD CLAY ST ACORN OAK AVE SOUND SEA AVE MAPLE WILLOW DRIVE ELM DRIVE CYPRESS DRIVE DRIVE CEDAR DRIVE HILLSIDE COURT CARROL DR - SR 1408 ° Duck 1 CYPRESS CEDAR DRIVE WILLOW DRIVE DRIVE MAPLE DRIVE CARROL DR - SR 1408 CAFFEYS HILLSIDE COURT COURT SEA TERN DRIVE QUARTERDECK DRIVE TRINITIE DR MALLARD DRIVE COURT RENE DIANNE ST FRAZIER COURT A OLD SQUAW DRIVE SR 1474 BUFFELL HEAD RD - SR 1473 SPRIGTAIL DRIVE SR 1475 CANVAS BACK DRIVE SR 1476 WOOD DUCK DRIVE SR 1477 PINTAIL DRIVE SR 1478 WIDGEON DR - SR 1479 BALDPATE DRIVE WHISTLING B SWAN DR N SNOW GEESE DR S SNOW GEESE DR SPYGLASS ROAD SANDCASTLE SPINDRIFTLANE COURT COURT PUFFER NOR BANKS DR SAILFISH SNIPE CT COURT WINDSURFER COURT SUNFISH COURT DUCK ROAD - NC 12 C § DUCK VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPT D SANDY RIDGE ROAD 2 TOPSAIL COURT SPINNAKER MAINSAILCOURT COURT FORESAIL COURT WATCHSHIPS DR BARRIER ISLAND STATION Duck -

State Historic Preservation Office Peter B

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Peter B. Sandbeck, Administrator Beverly Eaves Perdue, Governor Office of Archives and History Linda A. Carlisle, Secretary Division of Historical Resources Jeffrey J. Crow, Deputy Secretary David Brook, Director March 20, 2009 MEMORANDUM To: Mary Pope Furr Historic Architecture Group, HEU, PDEA NC Department of Transportation From: Peter Sandbeck Re: Mid-Cm-rituck Bridge Project, R-2576, Currituck and Dare Counties, CH 94-0809 We are in receipt of the March 11, 2009, letter from Courtney Foley, transmitting her Historic Architectural Resources Survey Report Addendum for the above referenced undertaking. Having reviewed the addendum, we offer the following comments. As noted in the report, the State Historic Preservation Office concurred on April 30, 2008 that the following properties are listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Girrituck Beach Light Station (CK1 — NR) Whalehead Club (CK5 — NR) Corolla Historic District (CK97 — DOE) Ellie and Blanton Saunders Decoy Workshop (CK99 — DOE) Dr. W. T. Griggs House (CK 103 — DOE) Currituck Sound Rural Historic District (DOE) Cle-01 09- Daniel Saunders House (DOE) (2,140 101 Samuel McHorney House (DOE) G4-00111 Coinjock Colored School (DOE) Oy_011,, On June 2, 2008, after further discussion with your staff, we also concurred that the Center Chapel A_ME Zion Church is eligible for the National Register. We also concur that the five properties in the subject addendum are eligible for listing in the National Register. They are: (Former) Grandy School (CK 40 — NR 1998) Jarvisburg Colored School (CK 55 — SL 1999) Dexter W. -

BUILDING Bridges to a Better Economy Viewfinder Ll 2007 Fa Eastthe Magazine of East Carolina University

2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy BUILDING BrIDGes to a better economy vIewfINDer 2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 feaTUres BUilDing BriDges 12 Creating more jobs is the core of the university’s newBy Steve focus Tuttle on economic development. From planning a new bridge to the Outer Banks to striking new partnerships with relocating companies, ECU is helping the region traverse troubled waters. TUrning The PAGE 18 Shirley Carraway ’75 ’85 ’00 rose steadily in her careerBy Suzanne in education Wood from teacher to principal to superintendent. “I’ve probably changed my job every four or five years,” she says. 18 22 “I’m one of those people who like a challenge.” TeaChing sTUDenTs To SERVE 22 Professor Reginald Watson ’91 is determined toBy walkLeanne the E. walk,Smith not just talk the talk, about the importance of faculty and students connecting with the community. “We need to keep our feet in the world outside this campus,” he says. FAMILY feUD 26 As another football game with N.C. State ominouslyBy Bethany Bradsher approaches, Skip Holtz is downplaying the importance of the contest. And just as predictably, most East Carolina fans are ignoring him. DeParTMeNTs froM oUr reaDers 3 The eCU rePorT 4 26 FALL arTs CalenDar 10 BookworMs PiraTe naTion Dowdy student stores stocks books 34 for about 3,500 different courses and expects to move about one million textbooks into the hands of students during the hectic first CLASS noTes weeks of fall semester. Jennifer Coggins and Dwayne 37 Murphy are among several students who worked this summer unpacking and cataloging thousands of boxes of new books. -

Capsizing of U.S. Small Passenger Vessel Taki-Tooo, Tillamook Bay Inlet, Oregon June 14, 2003

National Transportation Safety Board Washington, D.C. 20594 PRSRT STD OFFICIAL BUSINESS Postage & Fees Paid Penalty for Private Use, $300 NTSB Permit No. G-200 Capsizing of U.S. Small Passenger Vessel Taki-Tooo, Tillamook Bay Inlet, Oregon June 14, 2003 Marine Accident Report NTSB/MAR-05/02 PB2005-916402 Notation 7582B National National Transportation Transportation Safety Board Safety Board Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C. Marine Accident Report Capsizing of U.S. Small Passenger Vessel Taki-Tooo, Tillamook Bay Inlet, Oregon June 14, 2003 NTSB/MAR-05/02 PB2005-916402 National Transportation Safety Board Notation 7582B 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Adopted June 28, 2005 Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2005. Capsizing of U.S. Small Passenger Vessel Taki-Tooo, Tillamook Bay Inlet, Oregon, June 14, 2003. Marine Accident Report NTSB/MAR-05/02. Washington, DC. Abstract: This report discusses the June 14, 2003, accident in which the U.S. small passenger vessel Taki- Tooo capsized while attempting to cross the bar at Tillamook Bay, Oregon. A master, deckhand, and 17 passengers were on board the charter fishing vessel when it was struck broadside by a wave and overturned. The master and 10 passengers died in the capsizing; the deckhand and 7 passengers sustained minor injuries. The Taki-Tooo, with a replacement value of $180,000, was a total loss. From its investigation of the accident, the Safety Board identified the following major safety issues: decision to cross the bar, Tillamook Bay operations, and survivability. On the basis of its findings, the Safety Board made recommendations to the U.S. -

US Life Saving Service

A Publication of Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes Copyright 2015, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, P.O. Box 545, Empire, MI 49630 www.friendsofsleepingbear.org [email protected] This booklet was compiled by Kerry Kelly with research assistance from Lois Veenstra, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes and edited by Autumn Kelly. Information about the Life-Saving Service and its practices came primarily from the following two sources: The U.S. Life-Saving Service: Heroes, Rescues, and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard, by Ralph Shanks, Wick York, and Lisa Woo Shanks, Costano Books, CA 1996. Wreck Ashore: U.S. Life-Saving Service Legendary Heroes of the Great Lakes, by Frederick Stonehouse, Lake Superior Port Cities Inc., Duluth, MN, 1994. Information about the Sleeping Bear Point Life-Saving station came from the following two U.S. Government reports: Sleeping Bear Dunes Glen Haven Coast Guard Station Historic Structure Report, by Cornelia Wyma, John Albright, April, 1980. Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore Sleeping Bear Point Life-Saving Station Historic Furnishings Report, by Katherine B. Menz, July 20, 1983 Information about the North Manitou Island USLSS Station came primarily from Tending a Comfortable Wilderness: A History of Agricultural Landscapes on North Manitou Island, by Eric MacDonald and Arnold R. Alanen, 2000. Information about the South Manitou Island USLSS Station came primarily from Coming Through with Rye: An Historic Agricultural Landscape Study of South Manitou Island, Brenda Wheeler Williams, Arnold R. Alanen, William H. Tishler, 1996. Information about the rescues came from Wrecks, Strandings, and the Life-Saving Service/Coast Guard in the Manitou Passage Area by Neal R. -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

It'selementary

Fall 2021 Calendar of School Events September October • Library Card Sign Up Month • Child Awareness National Bully Prevention Month Month • Hispanic Heritage Month • National Book Month • National Principals’ Month Labor Day ........................... Sept. 6 World Smile Day ..................... Oct. 1 National Read A Book Day.............. Sept. 6 Fire Prevention Week ................. Oct. 3-9 National Teddy Bear Day . .Sept. 9 Columbus Day ...................... O ct. 11 Patriot Day .......................... S e pt. 11 Indigenous Peoples’ Day .............. O ct. 11 Citizenship Day ...................... Sept. 17 National School Lunch Week........ O c t . 1 1 - 1 5 Constitution Week................. Sept. 17-23 National Character Counts Week ..... O c t . 1 7 - 2 3 First Day of Autumn ................... Sept. 22 National School Bus Safety Week .... O c t . 1 8 - 2 2 National Punctuation Day ............. Sept. 24 Red Ribbon Week ................. Oct. 23-31 Halloween .......................... Oct. 31 November December • National Inspirational Role Models Month • Read a New Book Month • National Pear Month • Academic Writing Month • American Indian & Alaska • National Handwashing Awareness Month • Love Your Native Heritage Month Neighbor Month • Learn a Foreign Language Month National STEM/STEAM Day ............. Nov. 8 National Special Education Day .......... Dec. 2 Veterans Day ........................ N ov. 11 National Cookie Day ................... Dec. 4 National Young Readers Day........... Nov. 14 Letter Writing Day ....................... Dec 7 American Education Week .......... Nov. 14-20 Pearl Harbor Day........................ Dec 7 America Recycles Day ................ Nov. 15 Human Rights Day ..................... Dec. 10 I Love To Write Day.................... Nov. 15 Dewey Decimal System Day.............. Dec. 10 National Educational Support Bill Of Rights Day ....................... Dec. 15 Professionals Day..................... Nov. 17 Wright Brothers Day..................... Dec. 17 Thanksgiving Day ................... -

Wright Brothers Day, 2013

Proc. 9071 Title 3—The President Proclamation 9071 of December 16, 2013 Wright Brothers Day, 2013 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation On December 17, 1903, decades of dreaming, experimenting, and careful engineering culminated in 12 seconds of flight. Wilbur and Orville Wright’s airplane soared above the wind-blown banks of Kitty Hawk, North Caro- lina, pushing the boundaries of human imagination and paving the way for over a century of innovation. On Wright Brothers Day, our Nation com- memorates this once unthinkable achievement. We celebrate our scientists, engineers, inventors, and all Americans who set their sights on the impos- sible. America has always been a Nation of strivers and creators. As our next gen- eration carries forward this proud tradition, we must give them the tools to translate energy and creativity into concrete results. That is why my Ad- ministration is dedicated to improving education in the vital fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). We are working to broaden participation among underrepresented groups, and through Race to the Top, we are raising standards and making STEM education a pri- ority. Last year, we announced plans to create a national STEM Master Teacher Corps—a group of the best STEM teachers in the country, who will receive resources to mentor fellow educators, inspire students, and cham- pion STEM education in their communities. As we remember the Wright brothers, let us not forget another Wright who took up the mission of powered flight. Orville and Wilbur’s sister, Kath- arine, used her teacher’s salary to support the family and ran the Wrights’ bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, while her brothers worked in Kitty Hawk. -

December 2019

December 2019 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Happy Birthday to Hanukkah Read A New Set a reading goal International Mitten Tree Day Pearl Harbor Author Jan Brett! for December! Think Collect mittens from Begins Book Month 12! Volunteer Day Day Learn about the Give yourself the Get involved by family and friends to Read about how Jewish holiday by gift of reading by helping others. donate! this event forced the reading a book! reading new books! U.S. into war. 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 National Create a family Human Rights Is it cold outside? National Cocoa Day International traditions book! Warm up with a Brownie Day Day Gingerbread Sip on a warm cup Monkey Day "hot" book! of cocoa and read Brownies from a What are Human House Day Swing into some box or scratch, Rights and do you about Snow famous Monkey Make a Monsters! what's your have them? Gingerbread house books! favorite? you would love to 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Bill Of Rights Los Posadas Wright Brothers Learn about Arctic Happy Birthday to Happy Birthday to Winter Solstice Read and learn animals at the North Author Eve Bunting! Author Lulu It's the first day of Day Day and South poles. Delacre! What rights are you about this 9 day Design, build and fly Winter, can you spot most thankful for? Mexican a new kind of paper the signs? celebration! airplane. 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Sit back and watch Give the gift of time Take a train ride on Christmas Day Kwanzaa Begins Make cut out Card Playing your favorite stories to your family and the Polar Express! snowflakes! Read about the first Grab a drum and Day be read aloud to friends. -

Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place

ABSTRACT LEE, GABRIEL FRANCIS. Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place. (Under the direction of Matthew Morse Booker.) This thesis is an environmental history of the North Carolina Outer Banks that combines cultural history, political economy, and conservation science and policy to explain the entanglement of constructions, uses, and claims over the land that created by the late 20th century a complex, contested, and national place. It is in many ways a synthesis of the multiple disparate stories that have been told about the Outer Banks—narratives of triumph or of decline, vast potential or strict limitations—and how those stories led to certain relationships with the landscape. At the center of this history is a declension narrative that conservation managers developed in the early 20th century. Arguing that the landscape that they saw, one of vast sand-swept and barren stretches of island with occasional forests, had formerly been largely covered in trees, conservationists proposed a large-scale reclamation project to reforest the barrier coast and to establish a regulated and sustainable timber industry. That historical argument aligned with an assumption among scientists that barrier islands were fundamentally stable landscapes, that building dunes along the shore to generate new forests would also prevent beach erosion. When that restoration project, first proposed in 1907, was realized under the New Deal in the 1930s, it was followed by the establishment of the first National Seashore Park at Cape Hatteras in 1953, consisting of the outermost islands in the barrier chain. The idea of stability and dune maintenance continued to frame all landscape management and development policies throughout the first two decades after the Park’s creation. -

Cultural & Religious Calendar 2021 (PDF)

Cultural & Religious Calendar 2021 Dean of Students Office University of Illinois Springfield One University Plaza, MS FRH 178 Springfield, IL 62703-5407 https://www.uis.edu/deanofstudents Phone: (217) 206-8211 Office Hours Monday thru Friday 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. 1 Cultural & Religious Calendar 2021 May 1 Saturday First Day of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month May 1 Saturday Law Day May 1 Saturday Loyalty Day May 1 Saturday National Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Day May 1 Saturday Orthodox Holy Saturday May 2 Sunday Orthodox Easter May 3 Monday Orthodox Easter Monday May 5 Wednesday Cinco de Mayo May 6 Thursday National Day of Prayer May 6 Thursday National Nurses Day May 7 Friday Military Spouse Appreciation Day May 8 Saturday Lailat al-Qadr (Muslim) May 9 Sunday Mother's Day May 13 Thursday Ascension Day (Christian) May 13 Thursday Eid al-Fitr (Muslim) May 15 Saturday Armed Forces Day May 15 Saturday Peace Officers Memorial Day May 17 Monday Shavuot (Jewish Holiday) May 17 Monday Tax Day May 21 Friday National Defense Transportation Day May 22 Saturday National Maritime Day May 23 Sunday Pentecost (Christian) May 24 Monday Whit Monday (Christian) May 25 Tuesday National Missing Children's Day May 30 Sunday Trinity Sunday (Christian) May 31 Monday Memorial Day Jun 3 Thursday Corpus Christi (Christian) Jun 6 Sunday D-Day Jun 14 Monday Army Birthday Jun 14 Monday Flag Day Jun 19 Saturday Juneteenth Jun 20 Sunday Father's Day 1 Cultural & Religious Calendar 2021 Jun 20 Sunday June Solstice Jul 4 Sunday Independence Day Jul 16 -

December 16 Newsletter Good Morning Yavapai County!

December 16 Newsletter Good morning Yavapai County! I hope that everyone is enjoying their holiday season and not getting too stressed over holiday shopping! For any new members, my name is Sidney and I work at Yavapai County Community Health Services as the Exceptional Child Health Resource Coordinator. Welcome to the Yavapai Special Needs Support Network. My job is trying to help people feel more connected during these trying times. So again welcome! Today we are going to take a deeper dive into Kwanzaa. Kwanzaa began in the United States in 1966, therefore it is a relatively new holiday. One of the main goals in its creation was to create pride and unity around all African culture. The holiday is modeled after harvest festivals. Seven is a super important number when it comes to Kwanzaa. There are seven symbols, seven principles, and Kwanzaa is celebrated over seven nights. The seven symbols of Kwanzaa are mazao (the crops), mkeka (the mat), kinara (the candle holder), muhindi (the corn), mishumaa saba (the seven candles), kikombe cha umoja (the unity cup) and zawadi (the gifts). And the seven principles are unity (umoja in Swahili), self-determination (kujichagulia), collective work and responsibility (ujima), cooperative economics (ujamaa), purpose (nia), creativity (kuumba) and faith (imani). Like Hanukkah, lighting candles is a large part of Kwanzaa. Each candle represents one principle of Kwanzaa and one day. The colors of Kwanzaa have very specific meanings. The green symbolizes hope and the future and the red symbolizes the struggle of the people. Kwanzaa gifts are often homemade. Kwanzaa itself is not a religious holiday, so many people celebrate it along with Christmas or Hanukkah.