Chambers Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Difficulty in the Origins of the Canadian Avant-Garde Film

CODES OF THE NORTH: DIFFICULTY IN THE ORIGINS OF THE CANADIAN AVANT-GARDE FILM by Stephen Broomer Master of Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Fine Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2006 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Joint Program in Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Stephen Broomer, 2015 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Codes of the North: Difficulty in the Origins of the Canadian Avant-Garde Film Stephen Broomer Doctor of Philosophy in Communication and Culture, 2015 Ryerson University and York University Abstract This dissertation chronicles the formation of a Canadian avant-garde cinema and its relation to the tradition of art of purposeful difficulty. It is informed by the writings of George Steiner, who advanced a typology of difficult forms in poetry. The major works of Jack Chambers (The Hart of London), Michael Snow (La Region Centrale), and Joyce Wieland (Reason Over Passion) illustrate the ways in which a poetic vanguard in cinema is anchored in an aesthetic of difficulty. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

Speaking Clown to Power: Can We Resist the Historic Compromise of Neoliberal Art? GREGORY SHOLETTE

03_Cronin pg27-54 11/19/10 12:48 PM Page 27 Speaking Clown to Power: Can We Resist the Historic Compromise of Neoliberal Art? GREGORY SHOLETTE Clowns always speak of the same thing, they speak of hunger; hunger for food, hunger for sex, but also hunger for dignity, hunger for identity, hunger for power. In fact, they introduce questions about who commands, who protests.1 he transformation of the postwar welfare or “Keynesian” state economy into its current, neoliberal form has dramatically altered the relationship Tbetween labour, capital, and the state. As noted in the introduction to this book, globalization, privatization, flexible work schedules, financial schemes, and hyper-deregulated markets have plunged many individuals into a world of precarious labour, in which one’s very sense of “being” is in a constant, yet indeterminate state of risk. In one stroke, the 2008 global financial meltdown illuminated the details of risk society—painfully for many (profitably for a small group of others). Not surprisingly, some look to culture for a modicum of critical insight if not an entirely different vision of life and labour. The work of artists, it is alleged, provides self-knowledge and sometimes utopian alter- natives precisely because cultural creativity is said to be a unique form of sen- suous, nonproductive, self-directed, and therefore “autonomous,”labour. Art appears to exist separately from the “cultural pollution”of everyday commerce. But given that art is also a form of labour, is it not also affected by the recent changes in -

Annual Report 12

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 THE MUSEUM 2013 Samantha Roberts volunteers her time in our library archives. Happy visitors tour the exhibition L.O. Today during the opening reception. 2013 was a year of transition and new growth for London, our tour guides, board and committee Museum London. As we entered 2013, we were members, Museum Underground volunteers, and guided by our new Strategic Plan, which had the many others—who have done exceptional work to succinct focus of attracting “Feet, Friends, and support the Museum this past year and over the Funds” and achieving the goals of creating many years of the Museum's history. opportunities for dialogue—about art and history, about our community, and indeed, about our 2013 also saw us transition our membership organization through a wide variety of program into a “supporters” program that has experiences and opportunities for engagement. enabled the Museum to engage and connect with a much larger segment of our community. All We also embarked on a new model of volunteerism Londoners are now able to enjoy the benefits of that provided new and diverse opportunities for a participating in and supporting the Museum. The wide variety of people interested in supporting art continued commitment of our supporters has and heritage in the community. The reason for our enabled us to maintain Museum London as an renewed approach is the changing face of important cultural institution with a national volunteerism: today young people volunteer to reputation for excellence. support their professional and educational goals, new Canadians volunteer as a way to connect with The City of London chose to create a separate their new home and with potential employers, and board to manage Eldon House beginning January seniors offer up their years of experience and 1, 2013. -

Inanna Fall 2021 Catalogue

Smart books for people who want to read and think about real women’s lives. Inanna Fall 2021 Inanna Publications & Education Inc. is one of only a very few independent feminist presses in Canada committed to publishing fiction, poetry, and creative non-fiction by and about women, and complementing this with relevant non-fiction. Inanna’s list fosters new, innovative and diverse perspectives with the potential to change and enhance women’s lives everywhere. Our aim is to conserve a publishing space dedicated to feminist voices that provoke discussion, advance feminist thought, and speak to diverse lives of women. Founded in 1978, and housed at York University since 1984, Inanna is the proud publisher of one of Canada’s oldest feminist journals, Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. Our priority is to publish literary books, particularly by fresh, new Canadian voices, that are intellectually rigorous, speak to women’s hearts, and tell truths about the vital lives of a broad diversity of women—smart books for people who want to read Smart books for people who and think about real women’s lives. Inanna books are important resources, widely used in university courses across the country. Our books are essential for any want to read and think about curriculum and are indispensable resources for the feminist reader. A real women’s lives. 210 Founders College, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON M3J 1P3 Phone: 416.736.5356 | Fax: 416.736.5765 [email protected] | www.inanna.ca CONTENTS FALL 2021 FALL 2021 FRONTLIST: FICTION SERIES 2 FALL 2021 FRONTLIST: YOUNG FEMINIST SERIES 7 FALL 2021 FRONTLIST: SIGNATURE SERIES 8 FALL 2021 FRONTLIST: MEMOIR SERIES 9 FALL 2021 FRONTLIST: POETRY SERIES 12 SPRING 2021 POETRY AND FICTION SERIES 15 SPRING 2021 BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR 18 SPRING 2021 INANNA NON-FICTION 19 Inanna Publications & Education Inc. -

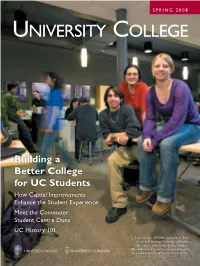

Building a Better College for UC Students

SPRING 2008 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Building a Better College for UC Students How Capital Improvements Enhance the Student Experience Meet the Commuter Student Centre Dons UC History 101 Front to Back: 2007/2008 Commuter Student Centre Don Madeline MacKenzie, 2007/2008 Off-Campus Commissioner Arman Hamidian, 2007/2008 Commuter Student Centre Don Deena UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Dadachanji in the UC Commuter Student Centre 54748-1 UC_08_SPRING_R16.indd 1 3/5/08 3:16:41 PM UC NOW CONTENTS A Message from UC Principal 2 A Message from UC Principal Sylvia Bashevkin A Message Sylvia Bashevkin 4 In Touch from UCAA Faculty and Staff News This edition of the University Recently Published President College magazine highlights Nicholas efforts to improve student life 6 Spotlight that we’ve undertaken during Meet Commuter Student Centre Dons Deena Dadachanji and Holland (UC ‘93) recent years, and hope with Madeline MacKenzie your help to pursue in the Let me begin with an ending. This is, with some sad- future. Our theme of building Come Back for Spring Reunion 2008 ness, my final message as the President of the UCAA 7 a better College draws inten- Welcoming all graduates of years ending in 3 and 8 as my wife, Tracy Hazlewood (a UC alumna), and tionally on the word building I are leaving Canada at the end of March for the – since so many of the fond Cayman Islands. And so, farewell! memories treasured by our alumni relate directly to the 8 Feature The focus for this edition of the magazine is building physical spaces at the heart of the St. -

Jack Chambers Fonds CA OTAG SC055

E.P. Taylor Research Library & Archives Description & Finding Aid: Jack Chambers Fonds CA OTAG SC055 Finding aid prepared by Judith Rodger, 1995–1996 Finding aid modified and description prepared by Amy Marshall With assistance from Gary Fitzgibbon, 2002/2009 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1G4 Canada Reference Desk: 416-979-6642 www.ago.net/research-library-archives Jack Chambers fonds Jack Chambers fonds Dates of creation: [ca. 1920]–1991, predominant 1961–1978 Extent: 5323 photographs 1.66 m of textual records and graphic materials 147 drawings 6 segments of film 3 audio discs 2 boxes of objects 1 model Biographical sketch: John Richard Chambers (1931–1978) was a Canadian painter and experimental filmmaker. Born in London, Ontario, he received his first art training there at H.B. Beal Technical School. After graduation in 1949 he left to study art in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. He returned to London in 1952 to study at the University of Western Ontario before leaving to travel in Europe the following year. During his travels in France, Jack Chambers met Picasso, who advised him to continue his studies in Spain. In 1957 he spent the summer in England where he met Henry Moore. Soon afterward he began his studies at the Escuela Central de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, graduating in 1959. His first exhibition was at the Lorca Gallery in Madrid in 1960. The following year he returned to London, Ontario. In Spain he had met Olga Sanchez Bustos, whom he married in Canada in 1963. They had two children, John (b. -

Artario 72” Curated by Noor Bhangu

Once A Total Art Happening: Revisiting “artario 72” Curated by Noor Bhangu November 24 - December 20, 2018 Curator’s Tours: December 8, 1 P.M.; December 14, 11:30 A.M. Kim Ondaatje, dom-tar with train, 1972. Photolitho/Serigraph in colour. Collection of the School of Art. “I’ve always felt that art has had too much mystique attached to it. It shouldn’t be something hidden away in art galleries. It should be a natural part of our everyday experience. Makes no difference who you are – whether you’re a Toronto art snob or a pulp worker in Kapuskasing – you should be able to go out and look at it and buy it if you like it. Cheaply. Just like books or records.”1 So began Peeter Sepp’s experiment of democratizing the arts in Canada. Using the model of the Multikonst, a Swedish travelling exhibition, artario 72 was designed as an “exhibition in a box” to be toured across Canada. Situated in an era of economic prosperity and cultural democratization, the exhibition focused on industrial means of production and dissem- ination, which promised to bring art cheaply and effectively to the Canadian people. On the evening of October 12, 1972, artario 72 opened simultaneously at nearly 500 different locations across Canada, including the School of Art at the Uni- versity of Manitoba.2 At its core, the project aimed to generate a pan-Canadian, visually-literate public that would learn to appreciate and support the Canadian arts in due time. Once an Art Happening prompts us to return to this historical exhibition and unpack the social life of visual arts in Canadian society of the late 60s and early 70s. -

The ART of LONDON 1830-1980 by Nancy Geddes Poole

The ART of LONDON 1830-1980 by Nancy Geddes Poole. e-Book Published by: Nancy Geddes Poole 2017 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Poole, Nancy Geddes, 1930- The Art of London, 1830-1980 Bibliography: p. ISBN 978-0-9959283-0-5 1. Art, Canadian – Ontario – London – History. 2. Art, Modern – Ontario – London – History. 3. Artists – Ontario - London. I. Title. N6547. L66P6 1984 709’.713’26 C85-098067-4 II Table of Contents Forward ......................................................................................................................III Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................ IX Chapter 1 The Early Years 1830-1854 ........................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Art in the Young City ....................................................................... 19 Chapter 3 Judson and Peel ................................................................................. 38 Chapter 4 Art Flourishes in the 1880s ........................................................ 56 Photograph Collection One ..................................................................................... 73 Chapter 5 London Women and Art ................................................................ 97 Chapter 6 The Turn of the Century ............................................................ 113 Chapter 7 Two Art Galleries for London ................................................. 123 Photograph Collection Two .................................................................................... -

Kazimir Glaz, the Centre for Contemporary Art and the Printmakers at Open Studio As Two Aspects of Printmaking Practice in the 1970S in Toronto

KAZIMIR GLAZ, THE CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART AND THE PRINTMAKERS AT OPEN STUDIO AS TWO ASPECTS OF PRINTMAKING PRACTICE IN THE 1970S IN TORONTO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY: ART AND ITS INSTITUTIONS BY ILONA JURKIEWICZ, BFA, HONOURS CARLETON UNIVERSITY OTTAWA, ONTARIO 1 DECEMBER, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87772-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87772-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A

JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham 1 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham Contents 03 Biography 09 Key Works 28 Significance & Critical Issues 33 Style & Technique 39 Where to See 44 Notes 45 Glossary 48 Sources & Resources 54 About the Author 55 Copyright & Credits 2 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham Critically and financially, Jack Chambers was one of the most successful Canadian artists of his time. Born in London, Ontario, in 1931, he had an insatiable desire to travel and to become a professional artist. Chambers trained in Madrid in the 1950s, learning the classical traditions of Spain and Europe. He returned to London in 1961 and was integral to the city’s regionalist art movement. Chambers was diagnosed with leukemia in 1969 and died in 1978. 3 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham EARLY YEARS John Richard Chambers was born in Victoria Hospital, London, Ontario, on March 25, 1931. (He signed his name “John” until around 1970, and he is often referred to as John Chambers.) His parents, Frank R. and Beatrice (McIntyre) Chambers, came from the area. His mother’s family farmed nearby; his father was a local welder. He had one sister, Shirley, less than a year older than he was. Chambers vividly related memories of his very happy childhood in his autobiography.1 Chambers’s mother, Beatrice (née McIntyre), and his father, Frank R. Chambers. Chambers’s art education started early and well. In 1944 at Sir Adam Beck Collegiate Institute in London, he was taught by the painter Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979), who encouraged Chambers to exhibit his early paintings.