Caractérisation De La Macrofaune Épibenthique De L'estuaire Et Du

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

Diversity and Phylogeography of Southern Ocean Sea Stars (Asteroidea)

Diversity and phylogeography of Southern Ocean sea stars (Asteroidea) Thesis submitted by Camille MOREAU in fulfilment of the requirements of the PhD Degree in science (ULB - “Docteur en Science”) and in life science (UBFC – “Docteur en Science de la vie”) Academic year 2018-2019 Supervisors: Professor Bruno Danis (Université Libre de Bruxelles) Laboratoire de Biologie Marine And Dr. Thomas Saucède (Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté) Biogéosciences 1 Diversity and phylogeography of Southern Ocean sea stars (Asteroidea) Camille MOREAU Thesis committee: Mr. Mardulyn Patrick Professeur, ULB Président Mr. Van De Putte Anton Professeur Associé, IRSNB Rapporteur Mr. Poulin Elie Professeur, Université du Chili Rapporteur Mr. Rigaud Thierry Directeur de Recherche, UBFC Examinateur Mr. Saucède Thomas Maître de Conférences, UBFC Directeur de thèse Mr. Danis Bruno Professeur, ULB Co-directeur de thèse 2 Avant-propos Ce doctorat s’inscrit dans le cadre d’une cotutelle entre les universités de Dijon et Bruxelles et m’aura ainsi permis d’élargir mon réseau au sein de la communauté scientifique tout en étendant mes horizons scientifiques. C’est tout d’abord grâce au programme vERSO (Ecosystem Responses to global change : a multiscale approach in the Southern Ocean) que ce travail a été possible, mais aussi grâce aux collaborations construites avant et pendant ce travail. Cette thèse a aussi été l’occasion de continuer à aller travailler sur le terrain des hautes latitudes à plusieurs reprises pour collecter les échantillons et rencontrer de nouveaux collègues. Par le biais de ces trois missions de recherches et des nombreuses conférences auxquelles j’ai activement participé à travers le monde, j’ai beaucoup appris, tant scientifiquement qu’humainement. -

Hydrozoa of the Eurasian Arctic Seas 397 S

THE ARCTIC SEAS CI imatology, Oceanography, Geology, and Biology Edited by Yvonne Herman IOm51 VAN NOSTRAND REINHOLD COMPANY ~ -----New York This work relates to Department of the Navy Grant NOOOI4-85- G-0252 issued by the Office of Naval Research. The United States Government has a royalty-free license throughout the world in all copyrightable material contained herein. Copyright © 1989 by Van Nostrand Reinhold Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1989 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88-33800 ISBN-13 :978-1-4612-8022-4 e-ISBN-13: 978-1-4613-0677-1 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0677-1 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means-graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems-without written permission of the publisher. Designed by Beehive Production Services Van Nostrand Reinhold 115 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10003 Van Nostrand Reinhold (International) Limited 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE, England Van Nostrand Reinhold 480 La Trobe Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Nelson Canada 1120 Birchmount Road Scarborough, Ontario MIK 5G4, Canada 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data The Arctic Seas. Includes index. 1. Oceanography-Arctic Ocean. 2. Geology-ArctiC Ocean. 1. Herman, Yvonne. GC401.A76 1989 551.46'8 88-33800 ISBN-13: 978-1-4612-8022-4 For Anyu Contents Preface / vii Contributors / ix 1. -

Larvae of Marine Bivalves and Echinoderms

V.L. KflSVflNOV>G.fl. KRVUCHKOVfl VAKUUKOVfl-LAIVICDVCDevn Scientific Cditor Dovid L pQiuson LARVAE OF MARINE BIVALVES AND ECHINODERMS V.L. KASYANOV, G.A. KRYUCHKOVA, V.A. KULIKOVA AND L. A. MEDVEDEVA Scientific Editor David L. Pawson SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIBRARIES Washington, D.C. 1998 Smin B87-101 Lichinki morskikh dvustvorchatykh moUyuskov i iglokozhikh Akademiya Nauk SSSR Dal'nevostochnyi Nauchnyi Tsentr Institut Biologii Morya Nauka Publishers, Moscow, 1983 (Revised 1990) Translated from the Russian © 1998, Oxonian Press Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lichinki morskikh dvustvorchatykh moUiuskov i iglokozhikh. English Larvae of marine bivalves and echinodermsA^.L. Kasyanov . [et al.]; scientific editor David L. Pawson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Bivalvia — Larvae — Classification. 2. Echinodermata — Larvae — Classification. 3. Mollusks — Larvae — Classification. 4. Bivalvia — Lar- vae. 5. Echinodermata — Larvae. 6. Mollusks — Larvae. I. Kas'ianov, V.L. II. Pawson, David L. (David Leo), 1938-III. Title. QL430.6.L5313 1997 96-49571 594'.4139'0916454 — dc21 CIP Translated and published under an agreement, for the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C., by Amerind Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 66 Janpath, New Delhi 110001 Printed at Baba Barkha Nath Printers, 26/7, Najafgarh Road Industrial Area, NewDellii-110 015. UDC 591.3 This book describes larvae of bivalves and echinoderms, living in the Sea of Japan, which are or may be economically important, and where adult forms are dominant in benthic communities. Descriptions of 18 species of bivalves and 10 species of echinoderms are given, and keys are provided for the iden- tification of planktotrophic larvae of bivalves and echinoderms to the family level. -

Preliminary Mass-Balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center December 2013 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Whitehouse, G. A. 2013. A preliminary mass-balance food web model of the eastern Chukchi Sea. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-262, 162 p. Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse1,2 1Alaska Fisheries Science Center 7600 Sand Point Way N.E. Seattle WA 98115 2Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean University of Washington Box 354925 Seattle WA 98195 www.afsc.noaa.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Penny. S. Pritzker, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. -

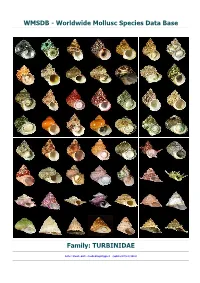

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

BEHAVIOURAL RESPONSE of NORTHERN BASKET STAR GORGONOCEPHALUS ARCTICUS to MECHANICAL STIMULATIONS J.-F Hamel, a Mercier

BEHAVIOURAL RESPONSE OF NORTHERN BASKET STAR GORGONOCEPHALUS ARCTICUS TO MECHANICAL STIMULATIONS J.-F Hamel, A Mercier To cite this version: J.-F Hamel, A Mercier. BEHAVIOURAL RESPONSE OF NORTHERN BASKET STAR GOR- GONOCEPHALUS ARCTICUS TO MECHANICAL STIMULATIONS. Vie et Milieu / Life & En- vironment, Observatoire Océanologique - Laboratoire Arago, 1993, pp.197-203. hal-03045834 HAL Id: hal-03045834 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-03045834 Submitted on 8 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. VIE MILIEU, 1993, 43 (4): 197-203 BEHAVIOURAL RESPONSE OF NORTHERN BASKET STAR GORGONOCEPHALUS ARCTICUS TO MECHANICAL STIMULATIONS J.-F. HAMEL and A. MERCIER Département d'océanographie, Université du Québec à Rimouski, Centre Océanographique de Rimouski, 310 allée des Ursulines, Rimouski (Québec), Canada G5L 3A1 GORGONOCEPHALUS RÉSUME - L'Ophiure ramifiée Gorgonocephalus arcticus, retrouvée dans les eaux OPHIURE profondes de l'estuaire du Saint-Laurent, montre une capacité de discrimination COMPORTEMENT tactile qui lui permet de répondre proportionnellement à diverses intensités de sti- MECANO-SENSIBILITE mulation. Une stimulation ponctuelle du disque provoque l'enroulement général des bras et la couverture du disque par les radii. Une comparaison de la vitesse du mouvement des bras, induite par différents niveaux de stimulation, montre que G. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 615:31

Vol. 615: 31–49, 2019 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published April 18 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12923 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Food sources of macrozoobenthos in an Arctic kelp belt: trophic relationships revealed by stable isotope and fatty acid analyses M. Paar1,5,*, B. Lebreton2, M. Graeve3, M. Greenacre4, R. Asmus1, H. Asmus1 1Wattenmeerstation Sylt, Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Hafenstraße 43, 25992 List/Sylt, Germany 2UMR 7266 Littoral, Environment and Societies, Institut du littoral et de l’environnement, CNRS-University of La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympes de Gouges, 17000 La Rochelle, France 3Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany 4Department of Economics and Business, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Barcelona Graduate School of Economics, Ramon Trias Fargas, 25-27, 08005 Barcelona, Spain 5Present address: Biologische Station Hiddensee, Universität Greifswald, Biologenweg 15, 18565 Kloster, Germany ABSTRACT: Arctic kelp belts, made of large perennial macroalgae of the order Laminariales, are expanding because of rising temperatures and reduced sea ice cover of coastal waters. In summer 2013, the trophic relationships within a kelp belt food web in Kongsfjorden (Spitsbergen) were determined using fatty acid and stable isotope analyses. Low relative proportions of Phaeophyta fatty acid trophic markers (i.e. 20:4(n-6), 18:3(n-3) and 18:2(n-6)) in consumers (3.3−8.9%), as well as low 20:4(n-6)/20:5(n-3) ratios (<0.1−0.6), indicated that Phaeophyta were poorly used by macro- zoobenthos as a food source, either fresh or as detritus. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM VoL 109 WMhington : 1959 No. 3412 MARINE MOLLUSCA OF POINT BARROW, ALASKA Bv Nettie MacGinitie Introduction The material upon which this study is based was collected by G. E. MacGinitie in the vicinity of Point Barrow, Alaska. His work on the invertebrates of the region (see G. E. MacGinitie, 1955j was spon- sored by contracts (N6-0NR 243-16) between the OfRce of Naval Research and the California Institute of Technology (1948) and The Johns Hopkins L^niversity (1949-1950). The writer, who served as research associate under this project, spent the. periods from July 10 to Oct. 10, 1948, and from June 1949 to August 1950 at the Arctic Research Laboratory, which is located at Point Barrow base at ap- proximately long. 156°41' W. and lat. 71°20' N. As the northernmost point in Alaska, and representing as it does a point about midway between the waters of northwest Greenland and the Kara Sea, where collections of polar fauna have been made. Point Barrow should be of particular interest to students of Arctic forms. Although the dredge hauls made during the collection of these speci- mens number in the hundreds and, compared with most "expedition standards," would be called fairly intensive, the area of the ocean ' Kerckhofl Marine Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. 473771—59 1 59 — 60 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. los bottom touched by the dredge is actually small in comparison with the total area involved in the investigation. Such dredge hauls can yield nothing comparable to what can be obtained from a mudflat at low tide, for instance. -

Trivialnamen Für Mollusken Des Meeres Und Brackwassers in Deutschland (Polyplacophora, Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Scaphopoda Et Cephalopoda)

> Mollusca 27 (1) 2009 3 3 – 32 © Museum für Tierkunde Dresden, ISSN 1864-5127, 15.04.2009 Trivialnamen für Mollusken des Meeres und Brackwassers in Deutschland (Polyplacophora, Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Scaphopoda et Cephalopoda) FRITZ GOSSELCK 1, ALEXANDER DARR 1, JÜRGEN H. JUNGBLUTH 2 & MICHAEL L. ZETTLER 3 1 Institut für Angewandte Ökologie GmbH, Alte Dorfstraße 11, D-18184 Broderstorf, Germany [email protected] 2 In der Aue 30e, D-69118 Schlierbach, Germany PROJEKTGRUPPE MOLLUSKENKARTIERUNG © [email protected] 3 Leibniz-Institut für Ostseeforschung Warnemünde, Seestraße 15, D-18119 Rostock, Germany [email protected] Received on July 11, 2008, accepted on February 10, 2009. Published online at www.mollusca-journal.de > Abstract German common names for marine and brackish water molluscs. – A list of common names of German marine and brackish water molluscs was compiled for the German coastal waters and the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the North and Baltic Seas. Main aim of this compilation is to give interested non-professionals better access to and understanding of sea shells and squids. As often long-lived and relatively stationary species, molluscs can provide a key function as water quality indicators. The taxonomic classifi cation was based on the Mollusca databases CLEMAM and ERMS (MARBEF). The list includes 309 species. > Kurzfassung Eine Liste deutscher Namen der marinen und Brackwasser-Mollusken der deutschen Küstengewässer und der Ausschließlichen Wirtschaftszone (AWZ) der Nord- und Ostsee wurde erstellt. Ziel der Zusammenstellung ist es, mit den Trivialnamen dem interessierten Laien die marinen Schnecken, Muscheln und Tintenfi sche etwas näher zu bringen. -

Soft Bottom Macrofauna of an All Taxa Biodiversity Site: Hornsund (77°N, Svalbard)

vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 309–326, 2010 doi: 10.2478/v10183−010−0008−y Soft bottom macrofauna of an All Taxa Biodiversity Site: Hornsund (77°N, Svalbard) Monika KĘDRA1*, Sławomira GROMISZ2, Radomir JASKUŁA3, Joanna LEGEŻYŃSKA1, Barbara MACIEJEWSKA1, Edyta MALEC1, Artur OPANOWSKI4, Karolina OSTROWSKA1, Maria WŁODARSKA−KOWALCZUK1 and Jan Marcin WĘSŁAWSKI1 1 Instytut Oceanologii, Polska Akademia Nauk, Powstańców Warszawy 55, 81−712 Sopot, Poland (*corresponding author) <[email protected]> 2 Morski Instytut Rybacki, Kołłątaja 1, 81−332 Gdynia, Poland 3 Katedra Zoologii Bezkręgowców i Hydrobiologii, Uniwersytet Łódzki, Banacha 12/16, 90−237 Łódź, Poland 4 Zakład Biologicznych Zasobów Morza, Zachodniopomorski Uniwersytet Technologiczny, K. Krolewicza 4, 71−550 Szczecin Abstract: Hornsund, an Arctic fjord in the west coast of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), was se− lected as All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI) site under EU 5th Framework Concerted Action BIOMARE (2000–2002), especially due to its pristine, undisturbed natural charac− ter. On the base of large material (89 stations located throughout the fjord and 129 Van Veen grab samples) collected during cruises of RV Oceania in July in 2002, 2003, 2005 and 2007 and literature search a comprehensive list of species recorded within Hornsund area, on the soft bottom with depth range of 30–250 m is provided. Over 220 species were identified in− cluding 93 species of Polychaeta, 62 species of Mollusca and 58 species of Crustacea. Spe− cies list is supported by information on the zoogeographical status, body length and biologi− cal traits of dominant species. Need for further research on Hornsund soft bottom fauna with more sampling effort is highlighted. -

Anatomy of Zetela Alphonsi Vilvens, 2002 Casts Doubt on Its Original Placement Based on Conchological Characters

SPIXIANA 40 2 161-170 München, Dezember 2017 ISSN 0341-8391 Anatomy of Zetela alphonsi Vilvens, 2002 casts doubt on its original placement based on conchological characters (Mollusca, Solariellidae) Enrico Schwabe, Martin Heß, Lauren Sumner-Rooney & Javier Sellanes Schwabe, E., Heß, M., Sumner-Rooney, L. H. & Sellanes, J. 2017. Anatomy of Zetela alphonsi Vilvens, 2002 casts doubt on its original placement based on con- chological characters (Mollusca, Solariellidae). Spixiana 40 (2): 161-170. Zetela is a genus of marine gastropods belonging to the family Solariellidae (Vetigastropoda, Trochoidea). The species Zetela alphonsi Vilvens, 2002 was origi- nally described using classical conchological characters from samples obtained from deep water off Chiloé, Chile, but no other features were recorded in the original description. In the present paper, taxonomically relevant characters such as the operculum, radula, and soft part anatomy are illustrated and described for the first time from a specimen of Zetela alphonsi from a new locality, a methane seep area off the coast of central Chile. We find that many features differ substantially from other members of the genus, including several which deviate from characters that are diagnostic for Zetela. Zetela alphonsi also lacks retinal screening pigment, giving the appearance of eyelessness from gross examination. Although pigmenta- tion loss has been reported in other deep sea genera, this feature has not been re- ported in any other members of Zetela. We reconstructed a tomographic model of the eye and eyestalk, and demonstrate that a vestigial eye is still present but exter- nally invisible due to the loss of pigmentation. Based on these new morphological characters, particularly observations of the radula, we suggest that the current placement of this species in the genus Zetela should be reconsidered.