Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

What Are the Different Types of Armorial Bearings?

FAQ Grants of Arms Who may apply for a Grant of armorial bearings? All Canadian citizens or corporate bodies (municipalities, societies, associations, institutions, etc.) may petition to receive a grant of armorial bearings. What are the different types of armorial bearings? Three categories of armorial bearings can be requested: coats of arms, flags and badges. A coat of arms is centred on a shield and may be displayed with a helmet, mantling, a crest and a motto (see Annex 1). A grant of supporters is limited to corporate bodies and to some individuals in specific categories. What is the meaning of a Grant of Arms? Grants of armorial bearings are honours from the Canadian Crown. They provide recognition for Canadian individuals and corporate bodies and the contributions they make both in Canada and elsewhere. How does one apply for Arms? Canadian citizens or corporate bodies desiring to be granted armorial bearings by lawful authority must send to the Chief Herald of Canada a letter stating the wish "to receive armorial bearings from the Canadian Crown under the powers exercised by the Governor General." Grants of armorial bearings, as an honour, recognize the contribution made to the community by the petitioner (either individual or corporate). The background information is therefore an important tool for the Chief Herald of Canada to assess the eligibility of the request. What background information should individuals forward? Individuals should forward: (1) proof of Canadian citizenship; (2) a current biographical sketch that includes educational and employment background, as well as details of voluntary and community service. They will also be asked to complete a personal information form protected under the Privacy Act, and may be asked for names of persons to be contacted as confidential references. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

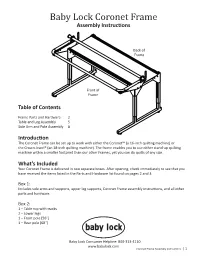

Coronet (BLCT16) Frame Assembly Instructions REVISED

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 REVISIONS ECO REV. DESCRIPTION DATE APPROVED A INITIAL RELEASE D D Baby Lock Coronet Frame Assembly Instructions Back of Frame C C Front of Frame Table of Contents Frame Parts and Hardware 2 BILL OF MATERIALS ENG-10007 Table and Leg Assembly 5 ITEM PART NUMBER DESCRIPTION QTY. Side Arm and Pole Assembly 8 1 QF05300-300 TABLE ASSY, TACONY FRAME 1 2 QF05300-402 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, A 2 B Introduction 3 QF05300-403 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, B 2 B The Coronet Frame can be set up to work with either the Coronet™ (a 16-inch quilting machine) or 4 QF05300-401 END LEG STAND 2 the Crown Jewel® (an 18-inch quilting machine). The frame enables you to use either stand-up quilting 5 QF09318-303 SCREW-M6x12 SWH 6 machine within a smaller footprint than our other Frames, yet you can do quilts of any size. 6 QF09318-07 Screw-M8x16 SBHCS 16 7 QF09318-108 LEVELING GLIDE 4 What’s Included 8 ENG-10005 ASSY-SIDE ARM RIGHT LF 1 Your Coronet Frame is delivered in two separate boxes. After opening, check immediately to see that you 9 ENG-10006 ASSY-SIDE ARM LEFT LF 1 have received the items listed in the Parts and Hardware list found on pages 2 and 3. 10 QF10005 POLE FRONT LF 1 11 QF10009 POLE REAR LF 1 Box 1: 12 QF10011 END CAP-REAR POLE LF 2 Includes side arms and supports, upper leg supports, Coronet Frame assembly instructions, and all other UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED: NAME DATE parts and hardware. -

2.2 the MONARCHY Republican Sentiment Among New Zealand Voters, Highlighting the Social Variables of Age, Gender, Education

2.2 THE MONARCHY Noel Cox and Raymond Miller A maturing sense of nationhood has caused some to question the continuing relevance of the monarchy in New Zealand. However, it was not until the then prime minister personally endorsed the idea of a republic in 1994 that the issue aroused any significant public interest or debate. Drawing on the campaign for a republic in Australia, Jim Bolger proposed a referendum in New Zealand and suggested that the turn of the century was an appropriate time symbolically for this country to break its remaining constitutional ties with Britain. Far from underestimating the difficulty of his task, he readily conceded that 'I have picked no sentiment in New Zealand that New Zealanders would want to declare themselves a republic'. 1 This view was reinforced by national survey and public opinion poll data, all of which showed strong public support for the monarchy. Nor has the restrained advocacy for a republic from Helen Clark, prime minister from 1999, done much to change this. Public sentiment notwithstanding, a number of commentators have speculated that a New Zealand republic is inevitable and that any move in that direction by Australia would have a dramatic influence on public opinion in New Zealand. Australia's decision in a national referendum in 1999 to retain the monarchy raises the question of what effect, if any, that decision had on opinion on this side of the Tasman. In this chapter we will discuss the nature of the monarchy in New Zealand, focusing on the changing role and influence of the Queen's representative, the governor-general, together with an examination of some of the factors that might have an influence on New Zealand becoming a republic. -

Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing

The UK Linguistics Olympiad 2018 Round 2 Problem 1 Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing Heraldry is the study of rank and heraldic arms, and there is a part which looks particularly at the way that coats-of-arms and shields are put together. The language for describing arms is known as blazon and derives many of its terms from French. The aim of blazon is to describe heraldic arms unambiguously and as concisely as possible. On the next page are some blazon descriptions that correspond to the shields (escutcheons) A-L. However, the descriptions and the shields are not in the same order. 1. Quarterly 1 & 4 checky vert and argent 2 & 3 argent three gouttes gules two one 2. Azure a bend sinister argent in dexter chief four roundels sable 3. Per pale azure and gules on a chevron sable four roses argent a chief or 4. Per fess checky or and sable and azure overall a roundel counterchanged a bordure gules 5. Per chevron azure and vert overall a lozenge counterchanged in sinister chief a rose or 6. Quarterly azure and gules overall an escutcheon checky sable and argent 7. Vert on a fess sable three lozenges argent 8. Gules three annulets or one two impaling sable on a fess indented azure a rose argent 9. Argent a bend embattled between two lozenges sable 10. Per bend or and argent in sinister chief a cross crosslet sable 11. Gules a cross argent between four cross crosslets or on a chief sable three roses argent 12. Or three chevrons gules impaling or a cross gules on a bordure sable gouttes or On your answer sheet: (a) Match up the escutcheons A-L with their blazon descriptions. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Town Unveils New Flag & Coat of Arms

TOWN UNVEILS NEW FLAG & COAT OF ARMS For Immediate Release December 10, 2013 Niagara-on-the-Lake - Lord Mayor, accompanied by the Right Reverend D. Ralph Spence, Albion Herald Extraordinary, officially unveiled a new town flag and coat of arms today before an audience at the Courthouse. Following the official proclamation ceremony, a procession, led by the Fort George Fife & Drum Corps and completed by an honour guard from the 809 Newark Squadron Air Cadets, witnessed the raising of the flag. The procession then continued on to St. Mark’s Church for a special service commemorating the Burning of Niagara. “We thought this was a fitting date to introduce a symbol of hope and promise given the devastation that occurred exactly 200 years to the day, the burning of our town,” stated Lord Mayor Eke. “From ashes comes rebirth and hope.” The new flag, coat of arms and badge have been granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, Dr. Claire Boudreau, Director of the Canadian Heraldic Authority within the office of the Governor General. Bishop Spence, who served as Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Niagara from 1998 - 2008, represented the Chief Herald and read the official proclamation. He is one of only four Canadians who hold the title of herald extraordinary. A description of the new coat of arms, flag and badge, known as armorial bearings in heraldry, is attached. For more information, please contact: Dave Eke, Lord Mayor 905-468-3266 Symbolism of the Armorial Bearings of The Corporation of the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake Arms: The colours refer to the Royal Union Flag. -

The Interface Between Aboriginal People and Maori/Pacific Islander Migrants to Australia

CUZZIE BROS: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND MAORI/PACIFIC ISLANDER MIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA By James Rimumutu George BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Newcastle March 2014 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor John Maynard and Emeritus Professor John Ramsland for their input on this thesis. Professor Maynard in particular has been an inspiring source of support throughout this process. I would also like to give my thanks to the Wollotuka Institute of Indigenous Studies. It has been so important to have an Indigenous space in which to work. My special thanks to Dr Lena Rodriguez for having faith in me to finish this thesis and also for her practical support. For my daughter, Mereana Tapuni Rei – Wahine Toa – go girl. I also want to thank all my brothers and sisters (you know who you are). Without you guys life would not have been so interesting growing up. This thesis is dedicated to our Mum and Dad who always had an open door and taught us to be generous and to share whatever we have. -

Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential. by Jack Carlson

Third Series Vol. V part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 218 Price £12.00 Autumn 2009 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume V 2009 Part 2 Number 218 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor +John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Noel COX, LL.M., M.THEOL., PH.D., M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam INTERNET HERALDRY Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential Jack Carlson In 1996, the Cambridge University Heraldic & Genealogical Society declared that 'genealogy and heraldry have both caught up with the latest computer technology' and that heraldists would soon prefer the internet to books: searchable heraldic databases and free, high-quality electronic articles and encyclopedias on the subject were imminent.1 Over the past thirteen years the internet's capabilities have likely surpassed what CUH&GS could have imagined. At the same time, it seems, the reality of heraldry's online presence falls somewhat short of the society's expectations.