Ingleside Presbyterian Church & Community Center And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFBAPCC January 2019 Postcard Newsletter

See newsletters in color at www.postcard.org Our name re�ects our location not our only area of interest. San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club January 2019 Meeting: Saturday, January 26, 11 :00AM to 3:00 PM Vol. XXXIV, No. 1 Ebenezer Lutheran Church, Mural Hall Browsing and Trading, 11 :30AM to 1:30PM - Meeting begins at 1:30PM San Francisco • Cover Card: Entrance to Confusion Hill? Visitors and dealers always welcome. IN • Meetin g Minutes Meeting Schedule on back cover. THIS • Kathryn Ayers "Lucky Baldwin" Program ISSUE Omar Kahn "Paper Jewels" Program PROGRAM: The Saturday, January 26 San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club meeting is from 11am to 3pm at Ebenezer Lutheran Church, Mural Hall (entrance off lower parking lot), 678 Portola Drive, San Francisco 94127. The meeting will be called to order at 1pm and the program will follow. (club meetings will be back at Fort Mason in February. Postcards and Space-Time Defy gravity at MYSTERY SPOTS across the US! Santa Cruz vortex is just one of many. Physics and the space-time continuum are turned upside down as the enigma of multidimensional reality is revealed in Daniel Saks presentation. LOCATION INFORMATION: Ebenezer Lutheran Church in Mural Hall The entrance to Mural Hall is off of the lower parking lot. 2 CLUB OFFICERS President: Editor: ED HERNY, (415) 725-4674 PHILIP K. FELDMAN, (310) edphemra(at)pacbell.net 270-3636 sfbapcc(at)gmail.com Vice President: Recording Secretary: NANCY KATHRYN AYRES, (415) 583-9916 REDDEN, (510) 351-4121 piscopunch(at)hotmail.com alonestar(at)comcast.net Treasurer/Hall Manager: Webmaster: ED CLAUSEN, (510) 339-9116 JACK DALEY: daley(at)postcard.org eaclausen(at)comcast.net MINUTES, October 20, 2018 Call to Order: The club meeting was called to order by President Ed Herny at 1:30 pm on the 20th of Oct. -

Crime Wave Back Story Residents Nervous, City Plans More Police

10 Community 30 Real Estate 18 Calendar Supervisor: Mark Dreamhouse: A July Events: July is a month Farrell unveils the city’s Divisadero classic 25 for the Marina and all of the Bay next budgets 7 Area to shine. Find out about Pet Pages the concerts, food events, film Food & Wine Political Animal: festivals, children’s activities, The Tablehopper: Say America’s Dog’ and more that make summer goodbye to La Boulange 10 adoption event 30 so enjoyable in S.F. 18 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 31ST YEAR VOLUME 31 ISSUE 07 JULY 2015 Reynolds Rap City business Bureaucracy Inc. If you think getting around the city is tough, try working with them BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS ou hear a lot these days about how hard it is just getting around San Francisco between the construction, the traffic, and the congestion. The Ybottom line is that San Francisco is a small city, with just 47.355 square miles of land (if you include the water, it’s nearly 232 square miles), and for many years, left-leaning activists and legislators kept new residential building at a minimum. Then Mayor Ed Lee decided to welcome (or more accurately, bribe) the Silicon Valley with enormous Mary Chapin Carpenter will perform on Aug. 2. PHOTO: COURTESY MARY CHAPIN CARPENTER tax breaks. The problem is that Silicon Valley is much larger, much more spread out, and made up mostly of single-family homes with two-car garages and plenty of Summer Sundays at Stern Grove free parking everywhere else. San Francisco had a dotcom boom once before, which BY LYNETTE MAJER quartet DakhaBrakha (July 19). -

Corbett Heights, San Francisco (Western Part of Eureka Valley) Historic Context Statement

Corbett Heights, San Francisco (Western Part of Eureka Valley) Historic Context Statement Prepared for Corbett Heights Neighbors Funded by Historic Preservation Fund Committee For Submittal to San Francisco Planning Department Prepared by Michael R. Corbett Architectural Historian 2161 Shattuck Avenue #203 Berkeley, California 94704 (510) 548-4123 mcorbett@ lmi.net Adopted by the Historic Preservation Commission on August 16, 2017 Historic Contex t Statement Corbett Heights F inal (Western Part of E ureka V alley) S an F rancisco, California TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1 A. Project Purpose .................................................................................................................................. 1 B. Historic Context Statements ............................................................................................................ 1 C. Project History and Personnel ......................................................................................................... 2 Sponsoring Organization ................................................................................................................ 2 Fiscal Sponsor .................................................................................................................................. 2 Volunteers ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Planning -

SFAC Civic Art Collection Monuments and Memorials

Means of Acc # Artist Title Date Medium Dimensions Acquisition Credit Line Location Collection of the City and County of San Francisco; Gift to the City of San Francisco by Lotta 1875.1 Anonymous Lotta's Fountain 1875 cast iron, bronze, glass 226 x 76 x 76 in. Gift Crabtree in 1875 Public Display : Market and Kearny St. : NE corner : District 3 1879.1 Anonymous Benjamin Franklin (1706‐1790) 1879 Pot metal 204 x 40 x 40 in. Gift Collection of the City and County of San Francisco; Commissioned; Gift of Henry D. Cogswell Public Display : Washington Square : Filbert, Stockton, Union and Powell St. : central green : District 3 1885.1.a‐e Happersberger, Frank James A. Garfield (1831‐1881) 1885 Bronze 200 x 203 x 208 in. Gift Collection of the City and County of San Francisco; Acquired in 1885 by public subscription Public Display : Golden Gate Park : John F. Kennedy Drive : Conservatory Lawn : District 1 1886.1 Conrads, Carl H. General Henry W. Halleck (1815‐1872) 1886 Granite 190 x 72 x 72 in. Gift Collection of the City and County of San Francisco; Gift of the Major General C.W. Callum Public Display : Golden Gate Park : John F. Kennedy Drive : near Tennis Courts : District 5 1887.1.a‐f Story, William Wetmore Francis Scott Key (1780‐1843) 1887 Bronze, travertine and marble 480 x 275 x 275 in. Gift Collection of the City and County of San Francisco; Gift of James Lick Public Display : Golden Gate Park : Music Concourse Drive : Bowl Drive : northeast end of Music Concourse : District 1 1889.1 Tilden, Douglas Ball Thrower 1889 Bronze 131 1/4 x 69 x 54 in. -

Adolph Sutro Papers, 1853-1915

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p3002p0 No online items Finding Aid to the Adolph Sutro Papers, 1853-1915 Finding Aid written by Bancroft Library staff; revised by Alison E. Bridger The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Adolph Sutro BANC MSS C-B 465 1 Papers, 1853-1915 Finding Aid to the Adolph Sutro Papers, 1853-1915 Collection Number: BANC MSS C-B 465 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Bancroft Library staff; revised by Alison E. Bridger Date Completed: May 2007 © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Adolph Sutro papers Date (inclusive): 1853-1915 Collection Number: BANC MSS C-B 465 Creators : Sutro, Adolph, 1830-1898 Extent: Number of containers: 23 boxes, 9 cartons, 1 oversize folder, and 1 tubeLinear feet: 20.75 Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: The Adolph Sutro Papers consists of correspondence, much of it relating to the Sutro Tunnel Company and to the Funding Bill; records of the Sutro Tunnel Company including cipher books; documents relating to property holdings in San Francisco, Alameda, San Mateo and Napa Counties; payrolls and reports for the Cliff House, Sutro Railroad, San Miguel Ranch, Sutro Baths, Sutro Library, and Sutro Heights; papers relating to Sutro's term as San Francisco Mayor; papers relating to Sutro's estate; and financial records. -

Historical Perspectives Vol. 21 2016

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 21 Article 1 2016 Historical Perspectives Vol. 21 2016 Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation (2016) "Historical Perspectives Vol. 21 2016," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 21 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol21/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Historical Perspectives Vol. 21 2016 Historical Perspectives Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History September 2016 Series II, Volume XXI Published by Scholar Commons, 2016 1 Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II, Vol. 21 [2016], Art. 1 "A Nightclub Map of Harlem" (1932), E. Simms Campbell Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol21/iss1/1 2 et al.: Historical Perspectives Vol. 21 2016 The Historical Perspectives Peer Review Process Historical Perspectives is a peer-reviewed publication of the History Department at Santa Clara University. It showcases student work that is selected for innovative research, theoretical sophistication, and elegant writing. Consequently, the caliber of submissions must be high to qualify for publication. Each year, two student editors and two faculty advisors evaluate the submissions. -

The History and Significance of the Adolph Sutro Historic District: Excerpts from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form Prepared in 2000

The History and Significance of the Adolph Sutro Historic District: excerpts from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form prepared in 2000. James P. Delgado Denise Bradley Paul M. Scolari Stephen A. Haller I. SIGNIFICANCE The area located on point Lobos and Lands End overlooking the Pacific Ocean in the westernmost portion of San Francisco has since the 1850s been developed and used by San Franciscans and visitors to the city to experience the scenery and recreational opportunities associated with the shoreline, beach, and ocean. Characteristics of this cultural landscape have combined activities related to the natural features of the area — scenic panoramic views, access to the beach and ocean for hiking and swimming, opportunities to see plant and animal communities — with “tourist” activities — restaurants, swimming, museums, buying souvenirs, and “having been there.” The foundation of this cultural landscape has always been the natural features — ocean, beach, cliffs, views, plant materials, animal life, and the sites, sounds, smells of the ocean. These have provided the reasons that people wanted to come to site and have wanted to shape it to reflect recreational attitudes of the specific time. Through the years the landscape has evolved, specific structures built to provide recreational- related activities have come and gone or changed, but the Sutro Historic Landscape District continues to be a vital place for San Franciscans and regional, national, and international visitors to the city to come and do all the things people have always done in this landscape by the sea. The Sutro Historic Landscape District is located just west of the Golden Gate, on a dramatic promontory overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where the rugged Point Lobos coastline turns abruptly south. -

The Haight & the Hierarchy: Church

The Haight & the Hierarchy: Church, City, and Culture in San Francisco, 1967-2008 Sarah Anne Morris Dr. Thomas A. Tweed, Advisor Dr. Kathleen Sprows Cummings, Second Reader Department of American Studies University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana March 16, 2016 CONTENTS List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………………….………..ii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….………… iii Abstract…………..…………………………………………………………………………………….…..v Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Methods and Sources…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………….….… 8 Significance of the Project……………………………………………………………….….……11 1. 1967 | Unity: The Trial of Lenore Kandel’s “The Love Book”…………………..…………………15 Church and City Take on “The Love Book:” Institutions Join Forces…………..…………….…19 The Trial: Defending Catholic Clean Culture………………………………………………….…22 An Unnerving Future: Catholicism and the City after the Love Book Trial……………….…….27 2. 1987 | Tension: Pope John Paul II Visits the City………………………………………..….……… 29 Majority without Authority: The Church Adjusts to Its New Status…………………………..….30 Church and City Navigate New Waters: Episodic Discomfort………………………………….. 34 Task Force on Gay/Lesbian Issues & AIDS: Sustained Conflict………………………..…..……37 Preparing for the Pope: Diplomacy Amidst Anger……………………………………….……… 41 A City Holds Its Breath: Pope John Paul II Visits San Francisco……………………….………. 44 A Mixed Bag: San Francisco Catholics Reflect on a Symbolic Visit…………………………… 47 3. 2008 | Division: Proposition 8 Tears Church and City -

The Fabulous Fior OVER 100 Years in an Italian Kitchen

THE FABULOUS FIOR OVER 100 YEARS IN AN ITALIAN KITCHEN By Francine Brevetti The History of San Francisco’s Fior d’Italia America’s Oldest Italian Restaurant, Established 1886 Second Edition THE FABULOUS FIOR Over 100 Years in Italian Kitchen by Francine Brevetti Second Edition Copyright © 2006 by San Francisco Bay Books 13966 Beitler Road Nevada City, CA 95959 www.fabulousfior.com ISBN 0-9753351-0-3 Printed in South Korea (?) Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written premission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact San Francisco Bay Books. To my mother Tecla Brevetti, my grandparents, Alberto Puccetti, who worked at the Fior d’Italia over 100 years ago, and his wife, Gemma Lenci Puccetti and Chef Gianfranco Audieri TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . 3 Introduction . 5 Acknowledgments . .7 CHAPTER I: The Gold Rush to 1900 . .9 Veal scaloppine . .16 CHAPTER 2: The Fior Presents Its Cuisine . 17 Osso buco . 21 Risotto with saffron . 22 CHAPTER 3: Shaking in 1906 . 23 Pasta and bean soup . .28 CHAPTER 4: From the Depths to the Heights . .29 Brown stock . .36 CHAPTER 5: Red Coffee . .37 Potato croquettes . .42 CHAPTER 6: Prohibition Be Damned. Celebrities Revel. .43 Eva Biagini’s Italian fried cream . .49 CHAPTER 7: The Great Depression . 51 Pavian soup . .56 CHAPTER 8: I Clienti (The Customers) . .57 Poached salmon . .64 CHAPTER 9: Lock the Doors. Lock the Windows. 1940-50 . -

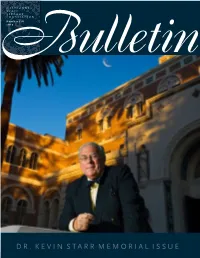

Bulletin Is 44 ��������Recent Contributors Published When We Are Able

CALIFORNIA S T A T E LIBRARY FOUNDATION Number 118 2017 DR. KEVIN STARR MEMORIAL ISSUE CALIFORNIA S T A T E LIBRARY FOUNDATION Number 118 2017 EDITOR 2 . .Kevin Starr Will Never Be Replaced: A Remembrance of the Gary F. Kurutz Historian and Author By Dr. William Deverell EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Kathleen Correia & Marta Knight 6 . .Reminiscences, Recollections, and Remembrances of Dr. Kevin O. Starr, 15th State Librarian of California COPY EDITOR M. Patricia Morris By Cameron Robertson BOARD OF DIRECTORS 12 ����������“A Letter to Dr. Kevin Starr, a.k.a. Dr. Feelgood” By Andrew St. Mary Kenneth B. Noack, Jr. SIDEBAR: A Letter from Dr. Starr to Taylor St. Mary President Donald J. Hagerty 16 ����������A Tribute to Dr. Kevin Starr Delivered at the 2017 Annual Vice-President Meeting of the Society of California Archivists By Mattie Taormina Thomas E. Vinson Treasurer 17 ����������California: An Elegy By Arthur Imperatore III Marilyn Snider 19 ����������Recollections of Kevin Starr By Marianne deVere Hinckle Secretary Greg Lucas 27 ����������When Kevin Starr Ran for the San Francisco State Librarian of California Board of Supervisors: 1984 By Michael S. Bernick JoAnn Levy Marilyn Snider 29 . .Celebrating Dr. Starr’s Genius, Generous Spirit and Phillip L. Isenberg Thomas W. Stallard Astonishing Vision By Dr. C. L. Max Nikias Mead B. Kibbey Phyllis Smith Gary Noy Angelo A. Williams 30 . .Eulogy of Dr. Kevin Starr Highlighting His Ten Years as Jeff Volberg State Librarian of California, 1994—2004 By Gary F. Kurutz Gary F. Kurutz Marta Knight 34 ����������The Sutro Library: Mirror for Global California, March 13, 2013 Executive Director Foundation By Dr. -

FALL 2011 Cole Fair Returns, Flags Flying Summer Social Is August 27 Sunday, September 25Th — 10 A.M

COLE VALLEY IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION CVolume XXIV VIASERVING ALL RESIDENTS NEWSOF THE GREATER HAIGHT ASHBURY FALL 2011 Cole Fair Returns, Flags Flying Summer Social is August 27 Sunday, September 25th — 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. This year’s Summer Social and Annual Meeting will be held at The Cole Valley Fair, renown among San Francisco street the Kezar Bar (corner of Cole and Carl) and will feature appetizers fairs for its appeal to families, is returning for its ninth year. Cole along with the usual choice of beverages. This is the time to meet Street between Grattan and Carl will be lined with tented booths, your neighbors. This is also the event at which we elect new officers. You will have an opportunity to bring up neighborhood issues in an informal setting. We who live in the Greater Haight Ashbury in 2011 share a particular set of benefits and challenges. Because of this we have more in common than we think. Please come be part of it. Kezar Bar and Restaurant Saturday, August 27, 1 - 4 p.m. RSVP: [email protected] $10 per person at door Members and their guests only Check Out Mayor Wannabees A candidate forum on September 22 will provide rare opportu- nity to see the mayoral candidates side by side discussing important For one day a year, it’s all about Cole Valley. issues at Cole Hall (UCSF) at 7 p.m. There are also plans to have a representative from the Department of Elections give a brief primer delicious food, beautiful crafts, some of the city’s most popular musicians, political candidates working the crowd, pets vying for “smartest,” and neighbors rediscovering each other. -

Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society

J OURNAL OF THE S AN F RANCI O S C M U S E M AND H I ORICAL S T S OCIETY V OL . 31 31 . N O . 1 . Volume 31 No. 1 Summer 2020 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Joe Barkett Chris O’Sullivan Rodger Birt David Parry Noah Griffin Christopher A. Patz Richard S. E. Johns Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Brent Johnson Darlene Plumtree-Nolte Rick Lenat Adriene Roche Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS DIREctOR OF EDUcatION AND PUBLIcatIONS Lana Costantini CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER Darlene Plumtree-Nolte The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TA FC BLE O ONTENTS THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE GERMAN-SPEAKING COMMUNITY in San Francisco, 1850–1924 by Stefanie E. Williams ..........................................................................................................................6 SUTRO’S SAN FRANCISCO— What’s Left? by William R. Huber ...........................................................................................................................52 WORLD WAR I AND THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO by Alan Ziajka ......................................................................................................................................72 Cover photo: Adolph Sutro.