The Impact of the Oil Industry on Local Communities in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection Rapid Assessment Field Mission Report Rier, Koch County

Protection Rapid Assessment Field Mission Report Rier, Koch County February 2017 1 Topography and Background Rier is proximal to Thar Jath Oil Field which once hosts a thriving community with an active market and decent livelihoods base prior to the crisis. Rier has been destroyed in armed clashes since 2014 which went through intermittently until 2016 as it serves as a military base for certain armed factions seeing that it is at the centre of Koch County and strategically placed for any offensives from armed elements. The oil companies have left ever since as a result of the December 2013 crisis. According to local authorities1, IDPs from other areas of Unity State do not stay in Rier for long as it’s mostly used as a transit spot, as there is no food, no outlook for economic activity and no available services. According to local authorities, the general security situation in Rier is calm. No conflicts and disputes were reported. No NGOs or other service providers are currently present in Rier, though strong necessities exist. Facts and Figures: Village (s) Rier Payam Jaak County Koch State Northern Liech Population 2772 persons (Unconfirmed) Ethnicity Nuer (Leek) Economy Nomadic pastoralist, agriculture and fishing Methodology This assessment targeted multi sector assessments, assessment of the coping mechanisms of the community and PSN identification in Rier, Koch County. The DRC team comprising of 7 staff conducted data collection through the following methods: a. Direct observations: Safety audit with observation visits to service delivery points; b. Short Forum Meetings with 10 men; 15 women; 8 persons with specific needs; c. -

Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved

HUMAN “They Burned It All” RIGHTS Destruction of Villages, Killings, and Sexual Violence WATCH in Unity State, South Sudan Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America “They Burned It All” ISBN: 978-1-6231-32620 Destruction of Villages, Killings, and Sexual Violence Cover design by Rafael Jimenez in Unity State, South Sudan Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................1 investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................... 6 organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................10 Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 BACKGROUND .........................................................................................................13 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, INTERNATIONAL LAW VIOLATIONS .......................................................................... -

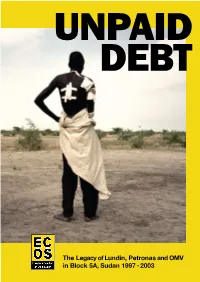

The Legacy of Lundin, Petronas and OMV in Block 5A, Sudan 1997 - 2003 the Legacy of Lundin, Petronas and OMV in Block 5A, Sudan 1997 - 2003 COLOPHON

The Legacy of Lundin, Petronas and OMV in Block 5A, Sudan 1997 - 2003 The Legacy of Lundin, Petronas and OMV in Block 5A, Sudan 1997 - 2003 COLOPHON Research and writing: European Coalition on Oil in Sudan Translations Swedish newspapers: Bloodhound Satellite images: PRINS Engineering ISBN/EAN 9789070443160 June 2010 Cover picture: wounded man, May 2002, near Rier, South Sudan. ©Sven Torfinn / Hollandse Hoogte. Contact details European Coalition on Oil in Sudan P.O. Box 19316 3501 DH Utrecht The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] This report is the copyright of ECOS, and may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ECOS, provided the integrity of the text remains intact and it is attributed to ECOS. This ECOS publication was supported by Fatal Transactions The European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS) is a large group of European organizations working for peace and jus- tice in Sudan. ECOS calls for action by Governments and the business sector to ensure that Sudan’s oil wealth contributes to peace and equitable development. www.ecosonline.org Fatal Transactions is a network of European and African NGO’s and research institutes. Fatal Transactions believes that if natural resources are exploited in a responsible way, they can be an engine for peace-building and contribute to the sustainable development of the country. www.fatal- transactions.org Fatal Transactions is funded by the European Union. The con- tents of this report can in no way be taken to reflect the views of either the European Union or the individual members of Fatal Transactions. -

Rapid Protection Assessment

Protection Assessment Buaw, Koch County, Unity State August 30 – September 10, 2014 Protection Assessment – Buaw Payam, Koch County, Unity State September 2014 Page 1 of 11 Table of Contents Protection Assessment ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 2. Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 4 To All Parties in Conflict ................................................................................................................................................ 4 To Protection Actors ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 To the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) .............................................................................. 4 To Other Humanitarian Actors ................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 4 4. Context Overview ....................................................................................................................... 5 5. Humanitarian Intervention....................................................................................................... -

Conflict Dynamics in Leer County, South Sudan: Issues, Barriers and Opportunities Towards Conflict Transformation

Conflict Dynamics in Leer County, South Sudan: Issues, Barriers and Opportunities Towards Conflict Transformation. November 2018 PREPARED BY: Coalition for Humanity South Sudan (CH) Buluk Area, Block III Plot 116,North of Falcon Hotel - Juba, South Sudan Tel: +211 (0) 917 094 299 E-mail: [email protected]. CONFLICT DYNAMICS IN LEER, SOUTH SUDAN 1 Acknowledgement Coalition for Humanity (CH) wishes to express its gratitude for the generous support by GIZ under the Strengthening Local Governance and Resilience Programme in South Sudan, which supported production of this report. Eric Momanyi - CH Consultant, provided technical Support in preparation of this report. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this discussion paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GIZ. 2 CONFLICT DYNAMICS IN LEER, SOUTH SUDAN Table of Contents Acknowledgement ............................................................................................ 2 Table of Contents ............................................................................................... 3 1. Background .................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Study objective ...................................................................................... 6 2. Literature Review ......................................................................................... 7 2.1. Background .......................................................................................... -

Oil Production in South Sudan: Making It a Benefit for All

CORDAID NAAM BU » SUMMARY REPORT MAY 2014 OIL PRODUCTION IN SOUTH SUDAN: MAKING IT A BENEFIT FOR ALL BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF OIL PRODUCTION ON COMMUNITIES IN UPPER NILE AND UNITY STATES OIL PRODUCTION IN SOUTH SUDAN: MAKING IT A BENEFIT FOR ALL FOREWORD This summary report introduces three county-specific reports, potential is significant in South Sudan, with oil and gas the full version of which will be published later this year. revenues estimated at more than 80 percent of gross domestic Together, the reports represent a first step towards helping product and more than 95 percent of South Sudan’s budget. South Sudan residents who live near oil and gas infrastructure from ensuring they are not negatively impacted by that Are there safety, environmental and reporting challenges development. The critical next step is to further build under- associated with oil and gas development? It is certainly the standing with host communities, their understanding of the perception of host communities that those challenges exist, nearby resource development and understanding by others of and in several cases, are significant. In our view, the opportu- their interests and needs in the context of the development. nities for engagement on mitigating the negative impacts, In the four months since this report was prepared, South improving the management of related risks and maximizing Sudan, the world’s newest country, continues to suffer from benefits for all are clear. Certainly, clear opportunities are not conflict, in the capital as well as in rural areas where there is simple to act on or even to discuss. -

S/2015/902 Security Council

United Nations S/2015/902 Security Council Distr.: General 23 November 2015 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on South Sudan (covering the period from 20 August to 9 November 2015) I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2241 (2015), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 December 2015 and requested me to report on the implementation of the mandate within 45 days. The present report provides an update to my previous report dated 21 August 2015 (S/2015/655) and covers developments from 20 August to 9 November. II. Political developments South Sudan peace process 2. Following the signing in Addis Ababa on 17 August of the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan by the leaders of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A in Opposition) and the former detainees, international and regional partners intensified efforts to persuade the President, Salva Kiir, to sign the peace agreement within the 15-day period granted for additional consultations. During a ceremony on 26 August in Juba, the President signed the agreement in the presence of regional leaders and other representatives of the international community. The Government distributed detailed reservations concerning 16 provisions of the agreement. 3. Subsequently, within the 72-hour deadline, the President and the former Vice- President, Riek Machar, each decreed a permanent ceasefire, instructing their forces to cease all military operations, to remain in their current positions and to return fire only in self-defence.