I Reading As Participating: a Study of Embodied Experiences of Reading and Writing by Ninette Pace Balzan This Thesis Is Submitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Property Transactions: April 2021

11 May 2021 | 1100 hrs | 087/2021 The number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property during April 2021 amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier. In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year. Residential Property Transactions: April 2021 Cut-off date: Final Deeds of Sale 4 May 2021 In April 2021, the number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier (Table 1). The value of these deeds totalled €228.4 million, 91.6 per cent higher than the corresponding value recorded in April 2020 (Table 2). With regard to the region the property is situated in, the highest numbers of fi nal deeds of sale were recorded in the two regions of Mellieħa and St Paul’s Bay, and Ħaż-Żabbar, Xgħajra, Żejtun, Birżebbuġa, Marsaskala and Marsaxlokk, at 150 and 143 respectively. The lowest numbers of deeds were noted in the region of Cottonera, and the region of Mdina, Ħad-Dingli, Rabat, Mtarfa and Mġarr. In these regions, 13 and 32 deeds respectively were recorded (Table 3). Chart 1. Registered fi nal deeds of sale - monthly QXPEHURIUJLVWHUHGILQDOGHHGV - )0$0- - $621' - )0$0- - $621' - )0$ SHULRG Compiled by: Price Statistics Unit Contact us: National Statistics Offi ce, Lascaris, Valletta VLT 2000 1 T. +356 25997219, E. [email protected] https://twitter.com/NSOMALTA/ https://www.facebook.com/nsomalta/ Promise of Sale Agreements In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year (Table 4). -

Our 2020 Beneficiaries

Our 2020 Beneficiaries (excluding Erasmus+ and European Solidarity Corps R 3) Beesmart Child Care Centre & Kindergarten Bishop's Conservatory Secondary School De La Salle College, Malta - Senior School Gozo College Rabat Primary Maria Regina College SPB Primary Maria Regina College, Naxxar Middle School Secretariat for Catholic Education KA 101 SMC Verdala St Albert the Great College St Theresa College, Lija-Balzan-Iklin Primary St Benedict College - OCP St Joseph, Mater Boni Consilii Paola St Nicholas College Rabat Middle School The Archbishop's Seminary Zejtun Primary A Dental Association of Malta Esplora Interactive Science Centre Ghaqda Kazini tal-Banda ITS Erasmus+ Malta Environmental Health Officers Association Malta Tourism Authority KA 102 MCAST Ministry for Health MITA Nature Trust NCFHE Planning Authority ITS MCAST KA 103 St. Martin's Institute UOM Inspire - Eden and Razzett Foundation KA 104 Jobsplus B'kara Youth Group Changemakers Malta Creative Youth KA 105 Cross Culture International Foundation Ccif CSR Malta Association Fgura United F.C. G.F. Abela University Of Malta Junior College Genista Research Foundation International Alliance for Integration and Sustainability Isla Local Council Malta Erasmus+ Network MALTA LGBTIQ RIGHTS MOVEMENT Network for European Citizenship and Identity - NECI Prisms Russian Maltese Cultural Association TERRA DI MEZZO (TDM) 2000 MALTA Upbeat Music House YOUNG EUROPEAN FEDERALISTS (JEF MALTA) Youth For A United World Malta Youtheme Foundation Zghazagh Azzjoni Kattolika ITS KA 107 MCAST UOM DDLTS -

PO Box. 42, Malta International Airport, Luqa LQA 5001 T : (+356)

Response Document to Notices of Proposed Amendment No. 2008-17A and NPA No. 2008-17B Comments Prior to an examination of the proposed amendments to Part FCL as proposed in NPA No. 2009-17B, due regard must be had to the contents of the Draft Opinion [NPA No. 2008-17A]. It is clearly understood, as declared in paragraph 2 of the Draft Opinion, that : “The European Aviation Safety Agency (the Agency) is directly involved in the rule -shaping process” in accordance with the functions set out in the Basic Regulation 1. The European Aviation Safety Agency, being an Agency of the European Union, does not have the function to enact law, however it is understood to be a duty of the Agency to present to the institution of the European Union a view of the matter being addressed which is correct and to forward proposals which are coherent with EU policy, in particular that any measures adopted are in conformity with the principle of proportionality. The aims pursued are the subject of the Basic Regulation – in a generic manner – as well as the Terms of Reference ToR FCL.001 reproduced in the Draft Opinion [NPA No. 2008-17A].These terms of reference are, inter alia : - “to establish in the form of essential requirements, high level safety objectives to be achieved by the regulations of pilot licensing” - “to require all pilots operating in the Community to hold a licence attesting compliance with common safety requirement covering their theoretical and practical knowledge, as well as they physical fitness” Whereas AOPA Malta agrees with the adoption of a harmonized approach to regulation on a European level to address the issue of pilot licensing in accordance with the terms of reference, it emphasis that all such regulation must conform with the principle of proportionality. -

Closure Closing Branch* Accounts Nearest Branches Automated Services in the Vicinity Date Transferred to 15-Feb Msida Gωira G

Closure Closing Branch* Accounts Nearest Branches Automated services in the vicinity Date transferred to 15-Feb Msida GΩira GΩira Óamrun branch Óamrun Msida (same premises) Msida (Junior College) GΩira branch 15-Feb Sta Venera B'Kara B'Kara Qormi Head office Óamrun Qormi branch Qormi Sta Venera (same premises) B'Kara branch Óamrun branch 15-Feb Naxxar Mosta Mosta Naxxar (same premises) San Ìwann Mosta branch B'Kara San Ìwann branch 15-Feb Attard Balzan Balzan Attard (same premises) Rabat Balzan branch Rabat branch Mdina 15-Feb Nadur Agency* N/A Rabat Gozo Nadur Agency (same premises) - to be installed Xag˙ra Agency Rabat branch 15-Feb Xag˙ra Agency* N/A Rabat Gozo Xag˙ra Agency (same premises) Nadur agency - to be installed Rabat branch 15-Mar Sliema, Manwel Sliema High Street Sliema High Street Sliema, Manwel Dimech Street Dimech Street GΩira Sliema High Street Branch GΩira branch The Point The Plaza Carlton Hotel 15-Mar Luqa Paola Paola Luqa (same premises) Ûejtun Paola branch Ûurrieq MCAST - Corradino Ûejtun Branch Ûurrieq Branch MIA arrivals lounge Tarxien Gudja outskirts - to be installed 30-Jun Campus ** San Ìwann ÌΩira Campus (same premises) San Ìwann Msida ex-branch Msida (Junior College) GΩira branch Mater Dei * These branches will offer a reduced service by appointment ** This branch will offer a reduced service Data tal- Ferg˙a li ser Kontijiet ser ji©u L-eqreb ferg˙at Servizzi awtomatizzati g˙eluq ting˙alaq* trasferiti lejn fil-qrib 15-Frar L-Imsida Il-GΩira Il-GΩira Ferg˙a tal-Óamrun Il-Óamrun L-Imsida (fl-istess post) L-Imsida -

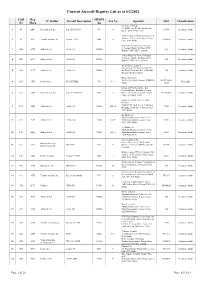

To Access the List of Registered Aircraft As on 2Nd August

Current Aircraft Registry List as at 8/2/2021 CofR Reg MTOM TC Holder Aircraft Description Pax No Operator MSN Classification No Mark /kg Cherokee 160 Ltd. 24, Id-Dwejra, De La Cruz Avenue, 1 41 ABW Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-28-160 998 4 28-586 Aeroplane (land) Qormi QRM 2456, Malta Malta School of Flying Company Ltd. Aurora, 18, Triq Santa Marija, Luqa, 2 62 ACL Textron Aviation Inc. Cessna 172M 1043 4 17260955 Aeroplane (land) LQA 1643, Malta Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 3 1584 ACX Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 544 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 4 1583 ACY Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 582 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Air X Charter Limited SmartCity Malta, Building SCM 01, 5 1589 ACZ Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 4th Floor, Units 401 403, SCM 1001, 590 Aeroplane (land) Ricasoli, Kalkara, Malta Nazzareno Psaila 40, Triq Is-Sejjieh, Naxxar, NXR1930, 001-PFA262- 6 105 ADX Reno Psaila RP-KESTREL 703 1+1 Microlight Malta 12665 European Pilot Academy Ltd. Falcon Alliance Building, Security 7 107 AEB Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-34-200T 1999 6 Gate 1, Malta International Airport, 34-7870066 Aeroplane (land) Luqa LQA 4000, Malta Malta Air Travel Ltd. dba 'Malta MedAir' Camilleri Preziosi, Level 3, Valletta 8 134 AEO Airbus S.A.S. A320-214 75500 168+10 2768 Aeroplane (land) Building, South Street, Valletta VLT 1103, Malta Air Malta p.l.c. -

Following in the Footsteps of St. Paul

YOUTH PILGRIMAGE TO MALTA JULY 26th - 31st 2020 Following in the footsteps of St. Paul WHY PILGRIMAGE Pilgrimage could be described as a meaningful journey to a sacred place. It provides the opportunity to step out of the non-stop busyness of our lives, to seek a time of quiet and reflection. It is a time of simply ‘being’ rather than always ‘doing’. For Christians, the reasons for going on pilgrimage include setting aside time for God; to help discern his plan; to be strengthened in our faith; and to feel inspired by the communion of saints who have gone before us. Pilgrimage can also be a highly sociable activity, allowing us to enjoy the company of others we meet. It gives us the chance re-energise mentally, physically and spiritually. WHY A PILGRIMAGE TO MALTA In between international World Youth Days, the Diocesan Youth Service runs a pilgrimage. In recent years, we have taken groups to York, Iona, and Santiago de Compostela. In this ‘Year of the Word’ we will be going to Malta to follow in the footsteps of one of the great writers of the epistles in the New Testament – St. Paul. It was in 60 AD, that St. Paul was on the way to Rome, to be tried when he was shipwrecked just off the coast of Malta during a storm. The people of Malta looked after the crew and St. Paul until they could continue with their journey. During this time, St. Paul preached the Gospel to the locals, who at the time were under Roman rule. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

A Newsletter of the Malta Study Center the MALTA STUDY CENTER at The

Fall 2017 A Newsletter of the Malta Study Center THE MALTA STUDY CENTER at the Dear Melitensians, Valletta houses some of the richest archival collections in the Mediterranean. Although the Archives of the Order of Malta in the National Library stand out as the preeminent example of this wealth in documents and history, several other smaller, less well-known archives detail this history of Malta and the Mediterranean in intimate detail. Chief among these are the confraternal archives found in Valletta. Th ese repositories record the charitable works and donations of their members dating back to the 16th century. I am happy to report that we began our project at the Archives of the Confraternity of Charity in May, 2017. Th e archive resides in a hidden tower within Saint Paul’s Shipwreck Church in Valletta. Th is preliminary work successfully digitized 90 manuscripts, focusing on the registers, account books, and confraternal foundations. More than half the collection remains to be digitized. Our success at the Confraternity of Charity led to greater interest in the Center from other confraternities of Malta, including the Archconfraternity of the Holy Rosary. Th anks to our partners in Malta, we will soon begin digitizing the Archconfraternity of the Holy Rosary as part of the private archive project co-sponsored by the Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti. Above: Digitizing the Archives of the We were fortunate to have two distinguished guests from Malta visit the Malta Study Confraternity of Charity in Valletta, Malta. Center in August and October. Francesca Balzan, Curator of the Palazzo Falson Historic House Museum, provided insights into the history of jewelry in Malta as part of our continued series of joint events with the Mediterranean Studies Collaborative at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. -

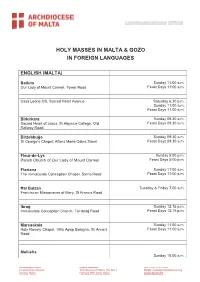

Holy Masses in Malta & Gozo in Foreign Languages

HOLY MASSES IN MALTA & GOZO IN FOREIGN LANGUAGES ENGLISH (MALTA) Balluta Sunday 11:00 a.m. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Tower Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Casa Leone XIII, Sacred Heart Avenue Saturday 6:30 p.m. Sunday 11:00 a.m. Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Birkirkara Sunday 09:30 a.m. Sacred Heart of Jesus, St Aloysius College, Old Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Railway Road Birżebbuġa Sunday 09:30 a.m. St George’s Chapel, Alfons Maria Galea Street Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Fleur-de-Lys Sunday 5:00 p.m. Parish Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Feast Days 5:00 p.m. Floriana Sunday 11:00 a.m. The Immaculate Conception Chapel, Sarria Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Ħal Balzan Tuesday & Friday 7:00 a.m. Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, St Francis Road Ibraġ Sunday 12:15 p.m. Immaculate Conception Church, Tal-Ibraġ Road Feast Days 12:15 p.m. Marsaskala Sunday 11:00 a.m. Holy Rosary Chapel, Villa Apap Bologna, St Anne’s Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Road Mellieħa Sunday 10:00 a.m. Shrine of Our Lady, Pope’s Visit Square Feast Days 10:00 a.m. Msida Sunday 10:00 a.m. Dar Manwel Magri, Mgr Carmelo Zammit Street Naxxar Sunday 11:30 a.m. Church of Divine Mercy, San Pawl tat-Tarġa Feast Days 11:30 a.m. The Risen Christ Chapel, Hilltop Gardens Sunday 11:30 a.m. Retirement Village, Inkwina Road Paceville Sunday 11:30 a.m. -

Local Government White Paper and Interrelated Regions and Districts

LOCAL GOVERNMENT WHITE PAPER AND INTERRELATED REGIONS AND DISTRICTS Perit Joseph Magro B.Sc.(Eng.)(Hons.), B.A.(Arch.) Update Note to the Addendum “Interrelated Regions and Districts for Malta and Gozo” Annexed to the Study Paper “Proposals For An Improved Malta Electoral System” This note proposes another solution of interrelated regions and districts, now based on the six regions as detailed in the Local Government White Paper. It also serves as a comparative study to the one put forward in the Addendum where a similar organizational structure of interrelated regions and districts for Malta and Gozo was proposed, with the districts also serving as electoral divisions. October 2018 LOCAL GOVERNMENT WHITE PAPER AND INTERRELATED REGIONS AND DISTRICTS Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 1.1 Reference to the Local Government White Paper 1.2 Reference to the Addendum 1.3 Main Objectives of This Update Note to the Addendum 1.4 Parameters Governing this Exercise 2. THE REGIONS AS ESTABLISHED IN THE WHITE PAPER ……………………………..…..………………………… 4 2.1 Maps of the Regions 3. ESTABLISHING THE DISTRICTS ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 3.1 Hamlets 3.2 Numbering of Regions and Districts 4. COMPARATIVE CASE STUDIES …………………………………………….……………..………………………………….. 6 4.1 Proposed Organizational Structure and Registered Voter Changes 4.2 District Seat Value 4.3 Registered Voter Changes between October 2007 and April 2018 5. CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Appendix 1: Map of the (White Paper) Regions and Proposed Districts …..…..….………………….……… 9 Appendix 2: Map of the Existing Regions of Malta ……………………………………………………………….…… 10 Appendix 3: Map of the Regions as Proposed in the White Paper ………………………………………….…. 11 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Reference to the Local Government White Paper The Local Government White Paper, published on 19th October 2018, refers to the existing five Regions of Malta as established by Act No. -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

Malta 2017 Crime & Safety Report

Malta 2017 Crime & Safety Report Overall Crime and Safety Situation U.S. Embassy Valletta does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The ACS Unit cannot recommend a particular individual or location and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE HAS ASSESSED VALLETTA AS BEING A MEDIUM- THREAT LOCATION FOR CRIME DIRECTED AT OR AFFECTING OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT INTERESTS. Please review OSAC’s Malta-specific webpage for proprietary analytic reports, Consular Messages, and contact information. Crime Threats Malta is a generally safe country that receives numerous foreign tourists on a yearly basis. However, crimes of opportunity and violent crime do occur. Most street crimes are non-violent and non-confrontational and range from scams to petty theft. Theft of cell phones, computers, money, jewelry, and iPods is common. Visitors should keep these items out of sight and only use them in safe locations. Most street criminals are unarmed and are not prone to gratuitous violence. Victims of street crime are often inattentive targets of opportunity. Women should keep purses zipped and in front of them. Wear the shoulder straps of bags across your chest. Keep your money, credit cards, wallet, and other valuables in your front pockets. In 2016, crime statistics revealed that theft was the predominate criminal offense, making up over half of the crimes committed in Malta. Assaults numbered under 1,000, with the peak being June, July, and August (height of tourism season). Nationwide crime rates are higher in areas frequented by tourists to include: St.