Urbanization in Viking Age and Medieval Denmark Medieval and Age Viking in Urbanization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Medieval Farming Communities in Northern Francia: Material Culture, Identity and Socio-Economic Structure of Rural Settlements, Ca

Early medieval farming communities in Northern Francia: material culture, identity and socio-economic structure of rural settlements, ca. 450-1000 AD Ewoud Deschepper and Wim De Clercq In stark contrast to the long-standing research history of early medieval cemeteries, it was only in 1973 that the first Merovingian settlement in Flanders was excavated at Kerkhove (ROGGE 1981; DE COCK 1996). After this it even took until the later 80’s and 90’s before new Merovingian rural settlements were examined, by Y. Hollevoet and B. Hillewaert in the region between Bruges and Oudenburg (see, for example, HOLLEVOET 2011; HOLLEVOET 2016). Since then, and with a marked increase because of development-led archaeology, several dozens of Merovingian and Carolingian sites have been discovered, not only in the western part of Flanders but also in Northern Belgium, in what is historically and geographically the southern part of the Campine region. The broader study and framing of these settlements with specific attention to their morphology and material culture as proxies for identity, socio-economic structure and the relations between different sub-regions both within Flanders and those neighboring it, has long been neglected. This is not the case for the coastal region, where important work has been conducted by D. Tys and P. Deckers (for example, TYS 2003; TYS 2004; LOVELUCK & TYS 2006; DECKERS 2014). However, a deeper inquiry into rural settlement, focusing on settlement structure and morphology, house building traditions, domestic pottery and the human-landscape interaction, is lacking for most of the actual territory of Flanders and for the coastal hinterland more specifically. -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

Rejseplan Talentcamp Svendborg 2020

REJSEPLAN TALENTCAMP SVENDBORG 2020 UDREJSE FREDAG D. 23. OKTOBER TalentCampDK vil sørge for, at der er rejseledere til stede. Rejselederne er med de tog, som er anført herunder og står på toget i hhv. Aalborg og København. Rejselederen fra København vil stå under uret på Hovedbanegården og rejselederen fra Aalborg vil stå i ankomsthallen på Aalborg St. (ved siden af 7Eleven). Tiderne er afgangstider. Sørg for at være i god tid, hvis du skal mødes med andre på stationen inden afgang. Ved aflysning af TalentCamps grundet COVID-19, refunderer TalentCampDK ikke togbilletterne. Derfor anbefaler vi, at man køber sin togbillet og pladsbillet i DSB-app eller DSB-netbutik, da disse billetter kan returneres af DSB uden gebyr indtil dagen før - læs evt. mere om dette på deres hjemmeside https://www.dsb.dk/. Alternativt kan kun en pladsbillet til nedenstående rejseplan købes, og selve rejsen betales med rejsekort på dagen. Vi gør også opmærksom på, at det er krav om mundbind i al offentlig transport og krav om pladsbillet i alle InterCity- og InterCityLyn-toge grundet COVID-19. Pladsbilletterne er for tiden gratis, og det er desuden pladsbilletten, der kan blive udsolgt, så derfor er det denne, som er vigtigst at bestille på forhånd. Vores rejseledere vil foruden hjælp med transporten, også være behjælpelige med at huske på at bruge mundbind, holde afstand osv. i den offentlige transport. KØBENHAVN H → SVENDBORG ICL 55 MOD STRUER ST. OG AALBORG ST. Rejselederne sidder i vogn 62 på plads 55 og 57. 14:56 København H. 16:07 Odense St. Bemærk at der kun er 6 min. -

Resultatliste - Paradisløbet 3

Resultatliste - Paradisløbet 3. maj 2015 Startgruppe 24 KM K2 Senior Herre K2 Jack Kristensen/Rune Kristensen Limfjorden 01:44:40 David Larsen/Lars Damgaard Silkeborg 01:45:25 Peter Jensen/Jeppe Glesner (DMC 35-39 år) Kolding 01:47:30 Joachim Umlauf/Thomas Brügge Preetzer TSV 01:54:28 Kent Jensen/Claus Thomsen (DMC 45-49 år) Kolding 02:13:45 Senior Mix K2 Jakob Lindbjerg Buthler/Christine Callesen Ålborg 01:58:56 Mette Grønborg/Max Jakobsen (DMC 40-44 år) MKC 02:01:55 Pia Jørgensen/Torben Lorentsen Horsens 02:12:22 Startgruppe 24 KM K1 Senior+U18 Senior Dame K1 Annemia Pretzmann Silkeborg 01:56:51 Anne-Sofie Winther (DMC U18) Silkeborg 01:57:36 Ditte Krogh Bak Skjold 02:14:21 Senior Herre K1 Nicolaj Blach Skanderborg 01:45:26 Mads Brandt Pedersen Silkeborg 01:46:27 Elias Ryom Kramer Limfjorden 01:47:03 Torben Thomsen Århus Kano og Kajak Klub 01:50:07 Dennis Möller ECST Raunheim 01:54:12 David Francis Kolding 01:54:35 Peter Larsen Sorø 01:57:01 Rasmus Hansen Odense 01:57:37 Daniel Svinth Storbjerg MKC 02:09:16 Julian Adsen Ålborg 02:29:59 Rasmus Frederiksen MKC 02:32:51 U18 Herre K1 Jonathan Dagnæs Silkeborg 01:45:28 Emil Skovgaard Silkeborg 01:50:12 Emil Kræmer Silkeborg 01:54:03 Adam Shiødt Maribo 02:08:39 3. maj 2015 Side 1 af 4 Startgruppe 24 KM K1 Masters 35-39 år Herre K1 Kasper Møller Skjold 01:59:07 Søren Hyttel Gladsaxe 02:00:57 Jimmy Buchmann (DMC 40-44 år) Vallensbæk 02:11:12 Kim Rubæk Ålborg 02:12:36 Jakob Færch Skjold 02:13:31 Mirko Milinkovic Sønderborg 02:20:44 Michael Gesellen (DMC 40-44 år) Gudenaa 02:28:40 40-44 år Dame -

Danish Isles

Denmark – Danish Isles Trip Summary Island hop through gently rolling countryside laced with extensive bike paths, historic ruins, royal castles, thatch-roofed farmhouses, and colorful fishing villages on this seven-day Danish Isles adventure. Itinerary Day 1: Helsingør We meet in the morning in Copenhagen • After a briefing, a bike safety talk and fitting, set out on your first ride • From Copenhagen we follow the Danish Riviera along a picturesque coastline dappled with small fishing villages • Explore the town of Klampenborg, a popular beach resort • In Helsingør, marvel at the old guns still intact at the Kronborg castle, admire the handsome half- timbered houses in the town center and stand before Hamlet’s memorial grave at Marienlyst Castle • Cool off with a dip on Julebaek beach before our welcome dinner and a comfortable night’s sleep at the Hotel Marienlyst • Overnight at Hotel Marienlyst (L, D) Day 2: Helsingør Wake up to stunning ocean views and a day spent exploring the sights in and around Helsingør • Stroll the beautiful statue-studded alleyways and gardens of Fredensborg Castle, the summer residence of the Danish Royal Family • This afternoon, enjoy a tasty lunch before touring the museum, chapels and gardens of Hillerød Castle, the most splendid achievement of the Danish Renaissance • Continue exploring on your own tonight and feel free to dine at any place that looks enticing • Overnight at Hotel Marienlyst (B, L) Day 3: Svendborg Morning transfer to Svendborg on the island of Funen, with a stop along the way in Roskilde -

Roskilde University (Ruc)

ROSKILDE UNIVERSITY (RUC) Roskilde Denmark Exchanges Portfolio V26/07/17 10:40 KEY FACTS Subject Area Biological Sciences Language Danish or English but Exchange students should select modules taught in English, B2 is required in English. Academic Calendar Semester 1 Early September to Late January Semester 2 Early February to Late June Module Catalogue Have a look through the module catalogue for modules available to exchange students. Fiancial Support As a UK Erasmus student, you are entitled to receive an Erasmus Grant for your time away at a participating Erasmus institution. 4 The City 5 The University 7 Accomodation & Living 8 TENT Contacts 9 Student Experiences CON ROSKILDE, DENMARK Roskilde, which is one of Denmark’s oldest cities, has Viking ships, a cathedral, a university, a national laboratory, and of course, Roskilde Festival. Roskilde was a Viking trading place more than 1000 years ago. At the Viking Ship Museum you can see remains of Viking ships from the 11th century and sail like a Viking out on the fjord. In the centre of Roskilde is Roskilde Cathedral, the burial place of Danish kings and queens. The church is an early example of French-influenced gothic architecture and features on UNESCO’s list of world cultural heritage. Roskilde also offers a modern cultural life with pedestrianised shopping streets and squares. During the summer, Roskilde Festival, which is northern Europe’s largest culture and music festival, attracts thousands of people. In July, fans pour into town for the four-day Roskilde Festival, which vies with Glastonbury for the title of Europe’s biggest rock festival. -

6030017 Denmark Danmark Kongerigst 6054053 Denmark G.S

Country County Title Film/Fiche # Item # Denmark Danish-Norwegian Research (Paleography) 6030017 Denmark Danmark Kongerigst 6054053 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 10 6030010 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 8 6030008 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 9 6030009 Denmark Genealogy Society Papers Series D16 6030017 Denmark Genealogy Society Papers Series D5 6030005 Denmark Maps, 1845-1916 68814 Denmark Military & Maritime Records 6039347 Denmark Pharmacists & Pharmacies, Catalogue, 1890 1440085 It 18 Denmark Postal Guide 6030021 Denmark Scandanavian Mission Emmigration 1852-1920 25696 Denmark WCOR-Danish Emigration 897215 It 15 Denmark WCOR-Danish Military Records 897215 It 13 Denmark WCOR-Danish Research 897215 It 14 Denmark WCOR-Denmark Emmigration 897215 It 1 Denmark WCOR-Town Records of Denmark 897215 It 12 Denmark Alborg Army Levying Rolls LAGD#56-116 1849 40418 Denmark Alborg Bislev Parish Records 1740-1883 43578 Denmark Alborg Blare Parish Records 1877-1916 408173 Denmark Alborg Census 1801 Nibe 39020 It 3 Denmark Alborg Census 1801 pt 39024 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Ars Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Fleskum Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Gislum Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Hansted Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Hellen Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Conscription Records, Military, 1811 40328 Denmark Alborg Ejdrup Parish Records 1813-1866 43349 Denmark Alborg Ejdrup Parish Records 1867-1891 408173 Denmark Alborg Flejsborg Parish Records 1725-1860 43571 Denmark Alborg Lundby -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

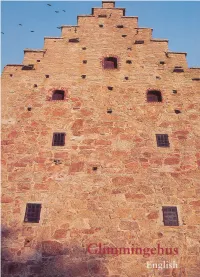

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

Varde-Januar-2020-Jobcenterindbliksrapport.Pdf

Varde kommunes Jobcenterindbliksrapport for Januar 2020 INDHOLD 1. Overblik 2. Borgere på offentlig forsørgelse 3. Tidlig indsats 4. Indsats for langvarige ydelsesmodtagere 5. Skærpet tilsyn det seneste år INDLEDNING Denne rapport er udarbejdet af Styrelsen for Arbejdsmarked og Rekruttering (STAR) og giver et indblik i kommunens resultater og indsatser på beskæftigelsesområdet samt kommunens status i forhold til skærpet tilsyn. Rapporten viser kommunens resultater på beskæftigelsesområdet ved at vise kommunens faktiske og forventede andel og antal offentligt forsørgede. Rapporten viser også, i hvilket omfang kommunens ydelsesmodtagere har modtaget en tidlig indsats, og i hvilket omfang langvarige ydelsesmodtagere har modtaget en indsats i form af samtaler og beskæftigelsesrettede tilbud i løbet af det seneste år. Rapporten er en del af udmøntningen af den politiske aftale om en forenklet beskæftigelsesindsats, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2020. Med aftalen får kommunerne større mulighed for fleksibelt at tilrettelægge omfang og timing af den aktive indsats efter den enkelte borgers behov. Den øgede frihed følges af en styrket monitorering og opfølgning på kommunernes indsats for at sikre, at ingen kommuner efterlader borgere passive uden indsats og kontakt med jobcenteret i længere perioder. Rapporten opdateres månedligt med nye data for samtaler og beskæftigelsesrettede tilbud. Tallene der vedrører kommunens resultater opdateres halvårligt. Bemærk, at data kan påvirkes af efterregistreringer mv indtil 3 måneder efter observationsmåneden. -

Lev Det Gode Liv I Kerteminde Kommune 2 Kerteminde Kommune

Lev det gode liv i Kerteminde Kommune 2 Kerteminde Kommune Velkommen til Kerteminde Kommune En kommune, hvor livet leves Hans Luunbjerg | Borgmester Kerteminde Kommune 3 Kerteminde Kommune har meget at byde på. Her er den smukkeste natur, et rigt kulturliv, historie, idyl, et sprudlende foreningsliv og ikke mindst et erhvervsliv i rivende udvikling. Takket være en infrastruktur, som skaber god forbindelse til resten af Danmark, samt muligheden for at placere sig tæt på motorvejen i Langeskov har flere større erhvervsvirksomheder valgt at få base i kommunen. Ifølge prognoserne vil denne udvikling fortsætte, og derfor er vi glade for, at der er blevet etableret en togforbindelse, som skal gøre det nemmere for både medarbejdere og forretningsforbindelser at komme til og fra Kerteminde Kommune. I byerne kommer flere specialbutikker til, som sælger unikke og nøje udvalgte råvarer til både borgerne og turisterne, der kommer hertil på grund af vores smukke beliggenhed. KERTEMINDE – HAVEN VED HAVET Kerteminde Kommune ligger helt ud til havet, og takket være vores unikke natur og nogle af landets bedste badestrande, kan vi årligt byde velkommen til tusindvis af besøgende, som både sejler og kører hertil. Borgerne i Kerteminde nyder også godt af vores smukke natur, hvilket kommer til udtryk i vores rige foreningsliv, hvor mange af aktiviteterne udfolder sig på vandet. Mange er født og opvokset her – en del er flyttet hertil, men fælles for alle borgere er et helt exceptionelt engagement for at drive foreninger og mødes på tværs – i Kerteminde Kommune vil vi nemlig fællesskabet! Vi glæder os til at byde dig, din familie og/eller din virksomhed velkommen til en kommune, hvor livet leves. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities.