The Last Adventure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

LUGGAGE Sometimes a Little Added Storage Capacity Is Just What You Need to Make Your Ride More Enjoyable

LUGGAGE Sometimes a little added storage capacity is just what you need to make your ride more enjoyable. Rain gear, extra clothing and basic supplies are easy to take along when you add luggage to your bike. NOT ALL PRODUCTS ARE AVAILABLE IN ALL COUNTRIES - PLEASE CONSULT YOUR DEALER FOR DETAILS. 733 734 LUGGAGE ONYX PREMIUM LUGGAGE COLLECTION Designed by riders for riders, the Onyx Premium Luggage Collection is constructed from heavy-weight, UV-stable ballistic nylon that will protect your belongings from the elements while maintaining their shape and color so they look as good off the bike as on. SECURE MOLLE MOUNTING SYSTEM The versatile MOLLE (Modular Lightweight Load- Carrying Equipment) mounting system allows for modular pouch attachment. Slip-resistant bottom UV-RESISTANT FINISH keeps the bag in place on your bike. Solution-dyed during fabric production for long-life UV-resistance even when exposed to the sun's harshest rays. 2-YEAR HARLEY-DAVIDSON® WARRANTY REFLECTIVE TRIM Reflective trim adds an extra touch of visibility to other motorists. DURABLE BALLISTIC NYLON 1680 denier ballistic polyester material maintains its sturdy shape and protects your belongings for the long haul. LOCKING QUICK-RELEASE MOUNTING STRAPS Convenient straps simplify installation and removal and provide a secure no-shift fit. Not all products are available in all countries – please consult your dealer for details. ORANGE INTERIOR OVERSIZE HANDLES GLOVE-FRIENDLY ZIPPER PULLS INTEGRATED RAIN COVER Orange interior fabric makes it easy to Soft-touch ergonomic handle is shaped Ergonomically contoured rubberized Features elastic bungee cord with a see bag contents in almost any light. -

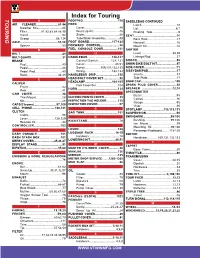

Index for Touring TOURING a FOOTPEG

Index for Touring TOURING A FOOTPEG...........................................125 SADDLEBAG CONTINUED AIR CLEANER...........................81-94 FORK Latch....................................10 Breather Kits..............................85 Cover........................................49 Lid..............................................6,7 Filter.................81,82,83,84,86,95 Dress Up Kit.................................46 Riveting Tool................................6 Insert.....................................92 Slider......................................48 SEAT.............................................16 Scoop.............................86,134 Tube/Slider Assembly..................48 Back Rest....................................17 AXLE..........................................55,56 FOOT BOARD............................117-124 Handrail......................................16 Spacer....................................55 FORWARD CONTROL.......................36 Mount Kit.....................................16 B FUEL CONSOLE DOOR..................101 SHIFTER BELT................................................41 H Lever.....................................38,39 BELT GUARD......................................31 HANDLEBAR.............................126-127 Linkage/Rod...............................37 BRAKE Control/Switch.............129,131 SHOCK........................................50 Pad........................................43 Cover..................................48,51 SHOW BIKE BOLT KIT........................97 Pedal........................................40 -

Luggage Sometimes a Little Added Storage Capacity Is Just What You Need to Make Your Ride More Enjoyable

903 luggage Sometimes a little added storage capacity is just what you need to make your ride more enjoyable. Rain gear, extra clothing and basic supplies are easy to take along when you add soft luggage to your bike. 904 LUGGAGE PREMIUM TOURING LUGGAGE COLLECTION Designed by riders, for riders. The Premium Luggage Collection features everything you ever wanted in a bag and more. Formed of superior heavy-weight ballistic nylon, these sturdy bags will maintain their shape and protect your belongings over the long haul and are tastefully styled to feel at home when carried into a nice hotel. 3M™ SCOTCHLITE™ REFLECTIVE TRIM SECURE SPANDEX MOUNTING SYSTEM Retrorefl ection technology enhances low- Smooth band slips over the passenger backrest light and nighttime visibility by bouncing for a snug fi t, eliminating the belts and fasteners light directly back to the source. that poke you in the back. UV-RESISTANT FINISH Coated to fi ght the sun’s harshest rays and maintain the rich black color. 2-YEAR HARLEY-DAVIDSON® WARRANTY QUICK-RELEASE MOUNTING STRAPS DURABLE BALLISTIC NYLON Convenient straps simplify installation and removal and provide a secure CONSTRUCTION no-shift fi t. Heavy-weight formed ballistic nylon helps bag retain its shape. INTERLOCKING D-RINGS OVERSIZE HANDLES GLOVE-FRIENDLY ZIPPER PULLS INTEGRATED RAIN COVER Multipurpose D-Rings simplify attach- Soft-touch ergonomic handle is shaped Large ergonomic-contoured pulls Ripstop nylon cover is coated to shed ment of other luggage, bungee cords for effortless transport to and from are easy to grip for quick on-the-go water and features 3M™ Scotchlite™ or cargo nets. -

Brand Building

BRAND BUILDING inside the house of cÉline Breguet, theinnovator. Classique Hora Mundi 5717 An invitation to travel across the continents and oceans illustrated on three versions of the hand-guilloché lacquered dial, the Classique Hora Mundi is the first mechanical watch with an instant-jump time-zone display. Thanks to apatented mechanical memorybased on two heart-shaped cams, it instantlyindicates the date and the time of dayornight in agiven city selected using the dedicated pushpiece. Historyisstill being written... BREGUET BOUTIQUES –NEW YORK 646 692-6469 –BEVERLY HILLS 310860-9911 BAL HARBOUR 305 866-10 61 –LAS VEGAS 702733-7435 –TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 –WWW.BREGUET.COM Haute Joaillerie, place Vendôme since 1906 Audacious Butterflies Clip, pink gold, pink, mauve and purple sapphires, diamonds. Clip, white gold, black opals, malachite, lapis lazuli and diamonds. Visit our online boutique at vancleefarpels.com - 877-VAN-CLEEF The spirit of travel. Download the Louis Vuitton pass app to reveal exclusive content. 870 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK H® AC CO 5 01 ©2 Coach Dreamers Chloë Grace Moretz/ Actress Coach Swagger 27 in patchwork floral Fluff Jacket in pink coach.com 800-457-TODS 800-457-TODS april 2015 16 EDITOR’S LETTER 20 CONTRIBUTORS 22 COLUMNISTS on Failure 116 STILL LIFE Mike Tyson The former heavyweight champion shares a few of his favorite things. Photography by Spencer Lowell What’s News. 25 The Whitney Museum of American Art Reopens With Largest Show Yet 28 Menswear Grooming Opts for Black Packaging The Texas Cocktail Scene Goes -

Pendragon Horse Breeding: Step 1: Lay out Expectation Pair Two

Pendragon Horse Breeding: Step 1: Lay out Expectation Pair two Classes of Horses (may be the same Class) together. The unmodified result will be the average of the Classes, rounded down. Breeding two horses more than 4 Classes apart is impossible. Dave wants to breed his prized Frisian Destrier with his Charger herd to produce a superior breed of warhorses. The Frisian Destrier is Class 9, while the Charger is Class 6. The expected result will be a Class 7 (9+6=15. 15/2 = 7.5, rounded down to 7). HORSE CLASSES 10: Shire Destrier 4: Courser 9: Frisian destrier 3: Palfrey 8: Destrier 2: Rouncy 7: Andalusian destrier 1: Sumpter 6: Charger 0: Nag 5: Poor Charger ______________________________________________________________ Step 2: During the following Winter Phase, roll both stewardship and horsemanship to determine the result. STEWARDSHIP HORSEMANSHIP CRITICAL SUCCESS FAILURE FUMBLE CRITICAL 1 2 3 4 SUCCESS 2 3 4 5 FAILURE 3 4 5 6 FUMBLE 4 5 6 7 BREEDING RESULT 1: Unusual horse of Exceptional quality 6: Disease: no birth, make extra survival roll for 2: Unusual horse or superior quality each horse involved in Breeding this foal. 3: Regular horse of regular quality 7: Bad disease: no new horses, make 2 extra 4: Regular horse of lower quality Survival rolls for *each* horse owned by the 5: No birth or stillbirth player. QUALITY Exceptional Quality: Add +2 to the foal’s Class Superior Quality: Add +1 to the foal’s Class Regular Quality: Add +0 to the foal’s Class. Lower Quality: Subtract 1d3 from the foal’s Class. -

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-Playing Games

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-playing Games Throughout the Middle Ages the horse was a powerful symbol of social differences but also a tool for the farmer, merchant and fighting classes. While the species varied considerably, as did their names, here is a summary of the main types encountered across Medieval Europe. Great Horse - largest (15-16 hands) and heaviest (1.5-2t) of horses, these giants were the only ones capable of bearing a knight in full plate armour. However such horses lacked speed and endurance. Thus they were usually reserved for tourneys and jousts. Modern equivalent would be a «shire horse». Mules - commonly used as a beast of burden (to carry heavy loads or pull wagons) but also occasionally as a mount. As mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses, they were particularly useful for strenuous support tasks, such as hauling supplies over difficult terrain. Hobby – a tall (13-14 hands) but lightweight horse which is quick and agile. Developed in Ireland from Spanish or Libyan (Barb) bloodstock. This type of quick and agile horse was popular for skirmishing, and was often ridden by light cavalry. Apparently capable of covering 60-70 miles a single day. Sumpter or packhorse - a small but heavier horse with excellent endurance. Used to carry baggage, this horse could be ridden albeit uncomfortably. The modern equivalent would be a “cob” (2-3 mark?). Rouncy - a smaller and well-rounded horse that was both good for riding and carrying baggage. Its widespread availability ensured it remained relatively affordable (10-20 marks?) compared to other types of steed. -

Galloping Onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse

Heidegger 1 Galloping onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse University of California, San Diego, Department of History, Undergraduate Honors Thesis By: Hannah von Heidegger Advisor: Ulrike Strasser, Ph.D. April 2019 Heidegger 2 Introduction As she prepared for the impending attack of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I of England purportedly proclaimed proudly while on horseback to her troops, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”1 This line superbly captures the two identities that Elizabeth had to balance as a queen in the early modern period: the limitations imposed by her sex and her position as the leader of England. Viewed through the lens of stereotypical gender expectations in the early modern period, these two roles appear incompatible. Yet, Elizabeth I successfully managed the unique path of a female monarch with no male counterpart. Elizabeth was Queen of England from the 17th of November 1558, when her half-sister Queen Mary passed away, until her own death from sickness on March 24th, 1603, making her one of England’s longest reigning monarchs. She deliberately avoided several marriages, including high-profile unions with Philip II of Spain, King Eric of Sweden, and the Archduke Charles of Austria. Elizabeth’s position in her early years as ruler was uncertain due to several factors: a strong backlash to the rise of female rulers at the time; her cousin Mary Queen of Scots’ Catholic hereditary claim; and her being labeled a bastard by her father, Henry VIII. -

RGP LTE Beta

RPG LTE: Swords and Sorcery - Beta Edition Animals, Vehicles, and Hirelings Armor: - Armor Rating 7 Small 80 Medium 170 There may come a time when the party of adventurers has more to carry or defend Large 300 than they can on their own or are traveling in land foreign to them. In these cases Heavy – Armor Rating +2 +30 the purchasing of animals and vehicles, and the hiring of aid may be necessary. The Saddlebag 5 following charts should serve as a general guide for such scenarios. Bridle and Reigns 15-25 For animals the price refers to the average cost the animal would be at a trader, Muzzle 7-14 while the upkeep refers to the average price of daily supplies the animal needs to be Harness 20-30 kept alive and in good health (the average cost of stabling for a night). Blinders 6-13 Horses Whip 6 Type Price Upkeep Cage 10-100 Packhorse (Pony) 50 1 Sled 20 Riding Horse (Rouncey*, Hackney**) 75 1 Smooth Hunting/Riding Horse (Palfrey) 250 2 Carts – 2-wheeled vehicles Swift Warhorse (Courser) 100 2 Item Cost Strong Warhorse (Destrier) 300 3 Small (Push) Handcart 25 Draft Horse (Percheron) 75 1 Large (Pull) Handcart 40 * General purpose ** Riding specific Animal (Draw) Cart 50 Riding Cart – 2 Person 50 Pony – A small horse suitable for riding by Dwarves, Paulpiens, and other smaller Chariot 130 folk, or carrying a little less than a human riders weight in items. Rouncey – A medium-sized general purpose horse that can be trained as a warhorse, Wagons – 4-wheeled vehicles, 2-4 animals to pull. -

Saddlebags and Supports

Section 16A Manuals, Bags, Lubricants Bungee Cords .................................... 3 Gasoila Sealant Available in hard setting red varnish or soft set blue/white with Cycle Covers .......................................1 teflon. Red sealant is the original sealer for sealing holes on po- rous surfaces and for use on the inside of crank cases and cam Goggles .............................................. 3 covers. Blue-white seals threaded joints on pipe threads and fittings. Both types are insoluble in oil, gas and solvents. Sold in 1/4 pint can that includes brush. Locks .................................................. 3 59474 Red varnish 59475 Blue/white Lubricants ............................................1 Manuals/Books.....................................2 Pouches .............................................10 Saddlebags and Supports ............ ..4-9 Self Adhesive Flame Trim 45134 8” chrome (each) 45133 6” chrome (each) Dow ‘Super Cover’ Motorcycle Cover Heavy weight polyester covers feature waterproof undercoating, Spectro Heavy Duty Fork Oil scratch resistant, aluminized panel reinforced grommets for use Type ‘E’ and ‘Heavy’ for superior damping and long lasting lubri- with a cable or bar lock and an elastic corded hem that ensures cation with anti-foaming, anti-rust and anti-corrosion additives. It a secure fit. PCP# 91701 and 91702 also include a flannel liner offers extreme temperature stability, minimizes fluid leakage and for added windshield protection. resists fading over a wide range of temperatures. Sold each -

LUGGAGE Sometimes a Little Added Storage Capacity Is Just What You Need to Make Your Ride More Enjoyable

747 LUGGAGE Sometimes a little added storage capacity is just what you need to make your ride more enjoyable. Rain gear, extra clothing and basic supplies are easy to take along when you add luggage to your bike. 748 LUGGAGE ONYX PREMIUM LUGGAGE COLLECTION Designed by riders for riders, the Onyx Premium Luggage Collection is constructed from heavy-weight, UV-stable ballistic nylon that will protect your belongings from the elements while maintaining their shape and color so they look as good off the bike as on. SECURE MOLLE MOUNTING SYSTEM The versatile MOLLE (Modular Lightweight Load- Carrying Equipment) mounting system allows for modular pouch attachment. Slip-resistant bottom UV-RESISTANT FINISH keeps the bag in place on your bike. Solution-dyed during fabric production for long-life UV-resistance even when exposed to the sun's harshest rays. 2-YEAR HARLEY-DAVIDSON® WARRANTY REFLECTIVE TRIM Refl ective trim adds an extra touch of visibility to other motorists. DURABLE BALLISTIC NYLON 1680 denier ballistic polyester material maintains its sturdy shape and protects your belongings for the long haul. LOCKING QUICK-RELEASE MOUNTING STRAPS Convenient straps simplify installation and removal and provide a secure no-shift fi t. ORANGE INTERIOR OVERSIZE HANDLES GLOVE-FRIENDLY ZIPPER PULLS INTEGRATED RAIN COVER Orange interior fabric makes it easy to Soft-touch ergonomic handle is shaped Ergonomically contoured rubberized Features elastic bungee cord with a see bag contents in almost any light. for eff ortless transport to and from zipper pulls are large and glove-friendly barrel lock tensioner to keep cover the bike. for on-the-go bag access.