Triabunna and Orford Communities and Coastal Hazards Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Days out East Camping and 4 DAYS of CAMPING and DAYWALKS in the TASMANIAN WILDERNESS Walking Tour

FACTSHEET DURATION: 4 days 3 nights 4 Days Out East Camping and 4 DAYS OF CAMPING AND DAYWALKS IN THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS Walking Tour KEY TO INCLUDED MEALS BELOW: (B): Breakfast (L): Lunch (D): Dinner Over 4 days from Hobart to Launceston. Experiencing the amazing variety of Tassie’s mild side, exploring Tasmania’s scenic, sunny east coast. Visit the “must see” places as well some local secrets along the way. Camp in great locations This tour starts in Hobart and finishes in Launceston. In four adventurous days on the East coast we visit the Tasman Peninsula and its giant sea cliffs, Freycinet Peninsula where we’ll climb up through the Hazards to view magical Wineglass Bay, we will walk through the spectacular Blue Tier mountains and forests, famous for its giant ferns and eucalyptus before ending up to the north east coast with arguably some of the world’s best beaches at the Bay of Fires. If you really want to experience the amazing variety of Tassie’s mild side we recommend this 4-Day tour exploring Tasmania’s scenic, sunny east coast and hinterland. Stay away from the crowds, enjoy a hike and relax with a camp fire dinner under the stars... Each day we participate in bush walks from 1−5 hours and travel by four- wheel-drive troop carriers which are ideal to access remote areas. Each night we experience bush camping and delicious meals with campfire cooking. When we camp we use tents or you can sleep under the stars and we supply cosy swags. -

Freycinet Resort Development

FREYCINET RESORT Expansion and Development Plans DESCRIPTION Stylish, comfortable accommodation in a wilderness setting on Tasmania’s beautiful East Coast. Freycinet Resort is a ten-cabin ecofriendly resort situated at Mt. Paul on the edge of the Freycinet National Park near Coles Bay on Tasmania’s beautiful East Coast. The resort has received development approval from Glamorgan Spring Bay Council to build an additional 28 units as visitor accommodation, a redeveloped reception, restaurant, and amenities building as well as a number of additional units as staff accommodation. The resort aims to provide a luxury experience for a reasonable price, striving for superior customer service for its guests. Situated on top of Mt. Paul the resort boasts skylines to both Friendly Beaches and across the Freycinet Peninsula. It is peppered with high quality art – sculptures and installations for visitors to experience as they wander the property. We also have a license to operate a guided walking experience through the fire trails and tracks of the Freycinet National Park which will be operated with the Resort as its base. Once the resort is increased in size to 38 units and with the guided walking experience that resort will contribute to the goal of increased visitation. Once the Tasmanian borders are open to tourists once again this will be a key contribution to East Coast tourism visitation and yield and the recovery from the impact of COVID-19. Aligning strongly with the T21 Visitor Economy Action Plan 2020-2022 this development will contribute to the recovery from the effects of COVID-19 on our tourism sector. -

Wheelchair Tennis Coaching Rolls Onto the Eastern Shore

1 A FREE PUBLICATION FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF CLARENCE AND SORELL www.easternshoresun.com.au AUGUST 2017 Your community. Your backyard. Your newspaper. Wheelchair tennis coaching rolls onto the Eastern Shore From left , Andrew Etherington, John Playle, Mickey Conallin, Tennis Tasmania chief executi ve offi cer Darren Sturgess, Grand Slam champion Todd Woodbridge, David Dickson, Katherine Kelly and Trent Constance. WHEELCHAIR tennis athletes thanks to the expansion of Tennis include a new wheelchair develop- guided from a junior to elite level. Mr Niforfer, who is the club and on the Eastern Shore now have Australia’s Wheelchair Tennis Devel- ment coach program, will help to Among those involved in the junior development coach at Rosny increased access to a network of opment Program. increase participation in the sport new program is local coaches David Park Tennis Club, said he passionate and specialised coaches The new measures, which and ensure players are appropriately Dickson and Martin Nidorfer. CONTINUES PAGE 4 HUGE range of Read all about our August landscape products: gardening tips on page 4 ► PINEBARKS ► LOAMS ► DECORATIVE GRAVELS FIREWOOD NOW Stephen Hassett ► AGGREGATES Dental Prosthetist ► MANURES AVAILABLE For regular updates & ► LIMES Proven Quality Over 33 Years Facebook only specials! ► PLANTS 20%* DELIVERIES TO ALL AREAS ► BAG PRODUCTS OFF ALL PLANTS ► AND MUCH MORE! *conditions apply Phone: 6248 4994 TRADING HOURS 131 PITTWATER ROAD 6244 6564 Monday - Friday: 8am - 4.30pm, Saturday: 9am - 4.30pm, Sunday: 10am - 3pm www.dentas.com.au 9 Clarence Street Bellerive 7018 CAMBRIDGE Closed Public Holidays 2 2 Eastern Shore Sun August 2017 Community News Council News Clarence City Council •Fire Maintenance Management of natural areas as per the Council Meetings ParksFire Management and ReservesEvents • variousOngoingMaintenance natural parks of maintenance.areawalking management tracks in natural plans. -

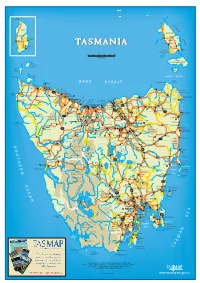

Tasmania.Pdf

Cape Wickham F U R N E A KING U X FLINDERS ISLAND Naracoopa Emita G Currie ISLAND R O Whitemark U P Yarra Creek Lackrana Grassy Strzelecki Lady Barron National Park 0 10 20 30 40 50 kilometres truwana CAPE BARREN ISLAND Three Hummock Island Hunter lungtalanana Island Clarke I Robbins Cape Grim BANKS STRAIT Island Swan BASS Cape Portland Island Stanley STRAIT Wiltshire SMITHTON Rocky Cape Tomahawk Black Port National Park Mt William Marrawah River Latta A2 National Park West Boat Harbour Point Table Cape Edith Creek Gladstone Mawbanna WYNYARD Bridport Eddystone Point Somerset Low Arthur River BURNIE Narawntapu Greens Head Ansons Bay National Park Beach GEORGE Arthur River Sulphur Creek Penguin Hawley Kelso TOWN Pipers Beach Derby Bay DEVONPORT Clarence Pt A8 River Yolla ULVERSTONETurners Beach 1 Beauty Pt SCOTTSDALE of Ridgley Port Nabowla Branxholm Sorell Beaconsfield Kayena Bangor Weldborough Fires Riana Forth A7 Ringarooma Deviot Lalla A3 larapuna Hampshire LATROBE Lilydale Binalong Bay Mersey Gravelly takayna Gunns Plains Exeter Beach B18 Dilston Tarkine Savage River Barrington Railton Rosevears Patersonia Frankford Grindelwald ST HELENS National Park Legana Nietta Sheffield North Wilmot Bridgenorth Nunamara Loongana River Lake Beaumaris Sandy Cape Waratah Roland HadspenBreadalbane Barrington Elizabeth Town LAUNCESTON Mathinna Gowrie Hagley Carrick Esk River Scamander Moina Park Falmouth A10 DELORAINE Savage River Ben Lomond Westbury 1 PERTH Western Junction Four Mile Creek Mole Creek Evandale National Park Ironhouse Point Golden Longford -

SWANSEA: the Hub of the East Coast Unpack Once and Explore the East Coast

SWANSEA: The Hub of the East Coast Unpack once and explore the East Coast P a g e | 1 A Leisurely Day in Swansea Locals love coming home to Swansea – we crest the hill near Kelvedon Beach and can feel the tension start to leave us. We want you to do the same – enjoy the slower pace, allowing yourself the time to relax and recharge! If you’re an early riser, this might mean catching a beautiful sunrise whilst walking along one of our many beaches all of which look out across Great Oyster Bay toward the Hazards at Coles Bay; soak up the peace and quiet and stop to take in the beauty. Swansea was settled in the 1820’s as Waterloo Point, and is one of Tasmania’s oldest towns. In fact many families living in Swansea today are descedants of these original settlers. Pop into the Visitor Information Centre and get a copy of the Heritage Walk booklet and you’ll be able to take a self-directed walk around town to learn about historical businesses, homes and iconic landmarks. You might even come across one of our older locals who’s willing to have a chat. You could also visit the East Coast Heritage Museum; there’s always a great display and passionate staff to share their knowledge. Stroll along Franklin Street (the main street) to find your perfect breakfast spot: - Barkmill Bakery, Artifakt Café & Gallery, Saltshaker. After breakfast, why not take a gentle walk right in the heart of Swansea; a walk that offers stunning coastal scenery. -

Canberra Bushwalking Club Newsletter Canberra Bushwalking

Canberra g o r F e e r o b o r r o Bushwalking C it Club newsletter Canberra Bushwalking Club Inc GPO Box 160 Canberra ACT 2601 Volume: 52 www.canberrabushwalkingclub.org Number: 11 2016 year in review December 2016 016 saw the continuation of great walks In reciprocation, in October, members of In this issue 2and great talks, a new walks challenge, the Hobart Walking Club visited Canberra Step up and Step out: an incentive program and were treated to many local walks to 2 Canberra Bushwalking that encouraged walking with at least give them an experience of the walks 20 different walk leaders, plus an informal enjoyed by the CBC. Floriade, was of Club Committee personal challenge of the Percies: an course included. 2 President’s prattle incentive program to visit many of the 2 Stan Marks – CBC’s new vantage points in the ACT. Some are not Sean Sunley gave us the challenge of as easy as you might think, as a ‘bag’ putting together an overnight camping life member requires you to touch the highest point of trip for under $50 and challenged walkers 2 Membership matters to do better. the feature. 3 Training Trifles This year also highlighted an exchange This year also saw some great enthusiasm 3 Review: CBC trip to from a walker of (hopefully) the next ‘program’ with the Hobart Walking Club. Tasmania March 2016 In March, CBC members travelled to generation. Isaac de Raadt not only went Tasmania to walk with their hosts, The on many trips, but wrote some reports on 6 Walks Waffle Hobart Walking Club. -

7 Days up the Tasmanian East Coast Day 1. Hobart

www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental 7 Days up the Tasmanian East Coast Hobart Hobart to Port Arthur Port Arthur to Triabunna (Maria Island) Triabunna to Bicheno Bicheno to St Helens St Helens to Scottsdale Scottsdale to Launceston Distance: 582km Day 1. Hobart Pick up your campervan in Hobart today. Allow at least 1 – 1.5 hours in order to familiarise yourself with the vehicle before you leave the depot. Hobart is the capital city of Tasmania, which means that there is a wide variety of activities and attractions suited to everyone. Mount Wellington is about a 30-minute drive west of Hobart, and is a must-see when you visit Hobart. Journey to the summit of the mountain, and if it’s a clear day, you can sometimes see all the way to the Tasman Sea. For something a little more active, you can trek along one of the many paths or even bring your bike. The natural environment is perfect for adventurous explorers. Stay: Discovery Holiday Parks, Hobart. www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental Day 2. Hobart to Port Arthur Depart this morning and take the A3 towards Bellerive. Turn right and follow Cole St/ A9 until you reach Port Arthur. Travel back to colonial Australia and visit the Port Arthur Historic Site, a World Heritage-listed attraction. Port Arthur was a penal settlement established in the 1830s, and was the home for many of the convicts that arrived from Britain. -

Candidate Information Pack

CANDIDATE INFORMATION PACK Considering Employment in Glamorgan Spring Bay Municipality Updated: August 2020 West Shelley Beach by H Chapman CONTENTS Our Region ............................................................................ 4 Our Municipality ............................................................... 6 Our ultimate vision of long-term success ........................ 7 Our guiding principles ....................................................... 7 Sunset in Swanwick by V Kay Triabunna Marina by J Goodrick Whales in the Bay by S Masterman Sheep auction by S Dunbabin Bluethroat Wrasse by J Smith Cambria Windmill by K Gregson PAGE 3 GSBC CANDIDATE INFORMATION PACK Our Region… The Municipal Environment build upon. Of the total number of interstate and The municipality of Glamorgan Spring Bay is international visitors coming to Tasmania, 30% situated amongst some of the most beautiful come to Glamorgan Spring Bay. Intrastate visitation coastal scenery in Tasmania. It has an area of is also strong, with 53% of dwellings across the 2,522 square kilometres and is bounded by municipality being holiday homes. During holiday the Denison River in the North and the base periods the overall population more than doubles and this has implications for infrastructure and of Bust Me Gall Hill in the South. The western boundary essentially follows the ridgeline of the service provision. The highest numbers of holiday Eastern Tiers. It is 160 kilometres from end to homes are in Coles Bay and Orford. end and contains two significant National Parks, Schools and Childcare Freycinet and Maria Island. Each of the main townships is serviced by a state Glamorgan Spring Bay Council provides a owned primary school (Kindergarten to Grade 6). wide range of services including roads and Triabunna has a district school years 7-10. -

Seaspeak GLAMORGAN SPRING BAY COUNCIL NEWS

SeaSpeak GLAMORGAN SPRING BAY COUNCIL NEWS A WORD FROM THE MAYOR ear Reader, DCouncil welcomes Keith Pyke as your elected representative, after a ballot-paper countback, following the sad passing of Councillor Michael Kent in December. Council welcomes Daniel Smee as the Acting General Manager whilst General Manager David Metcalf is on leave. The Glamorgan Spring Bay Citizen Award recipients this year were Gavan Barber and David Kirk. The Triabunna Community Hall was filled to capacity to celebrate and thank Gavan and David for their contribution to the community. In March I had the privilege of conducting a Citizenship Ceremony. Congratulations to our new Australian Citizens, Anne Held and Ryan Hodson. Your Council has been busy over the past few months as we, your elected members, work collaboratively on a number of local issues and opportunities. Paddy’s Paddock In January I was taken on a tour of the Spring Bay Mill site and nearby Paddy’s Paddock by Graeme Wood, Anna Cerneaz and Marcus Ragus. There is a great deal of work that has been completed on site with innovative, fun and exciting plans being put in to action. I was so impressed by Paddy’s Paddock that I asked Graeme to share the story of the garden with SeaSpeak readers. The article “All things good and delicious” is included in this edition! Council will continue to bring you articles showcasing local businesses working with community in positive and inspiring ways. Cranbrook In February Council held a Community Connect Session at the Cranbrook Hall which was followed by a workshop delivered by DPIPWE Water Management regarding the Swan River. -

Parent Handbook 2019

TRIABUNNA DISTRICT SCHOOL PARENT HANDBOOK 2020 WELCOME On behalf of our staff, students and wider school community I extend our warmest welcome. Triabunna District School is situated in spacious grounds at the gateway to the township of Triabunna. The school has a combination of modern and historic buildings overlooking beautiful Spring Bay and majestic Maria Island in the distance. Our school has a long history; the Triabunna State School being continuously open since 1863. With many modifications over the years, the school now provides a co-educational facility for K- 6 students and a Birth to 4 program for children from our township and for 7-12 students from across our Municipality including Swansea, Little Swanport, Triabunna, Orford and Buckland. There are approximately 155 students in the school, equally divided across the Primary and Secondary sections. Our K–12 facility provides a unique context where whole school approaches have been adopted to ensure the best learning opportunities to meet the educational needs of all students. Our vision is underpinned by the Department Of Education values of Aspiration, Growth, Resilience and Courage as well as our school values of Respect, Resilience and Growth. We encourage creative thinking and work to develop problem solving skills. We strive to develop preparedness for life-long learning that fosters a positive attitude by valuing and celebrating achievement in its many forms. These aims and objectives can only be achieved by establishing close, three-way partnerships between parents, staff and students. As such, we welcome our new students and their whole family to our school community and look forward to our ongoing collaborative work that ensures that learners are first – connected and inspired. -

EAST COAST SERVICES Triabunna, Orford, Swansea

EAST COAST SERVICES Triabunna, Orford, Swansea (Including out of area services which can be accessed by phone or online) May 2016 The Triabunna School Community Hub project, Beyond Random Acts, is supported by Primary Health Tasmania under the Primary Health Networks program – an Australian Government initiative, and the Community Support Levy through the Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services. The project partners Colony 47, Triabunna District School, EastCoast Regional Development Organisation (ERDO) and Glamorgan Spring Bay Council in delivering a program between the school, community and families to identify support needs and connect with services which reduce barriers to community participation. The involvement of the Spring Bay Medical Centre and Sandra (Harry) Higgs is central to program delivery. Index Section Page Health and Allied Services ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Emergency Shelters, Accommodation and Support ............................................................ 14 Education, Training, Employment ....................................................................................... 16 Student Accommodation and Financial Support ................................................................ 21 Financial .............................................................................................................................. 25 Community and General Assistance ................................................................................... 25 Child Care .......................................................................................................................... -

Draft of Great Oyster Bay Plan

GREAT OYSTER BAY AND MERCURY PASSAGE MARINE FARMING DEVELOPMENT PLAN OCTOBER 1998 (REVIEWED NOVEMBER 2007) (MODIFIED 17 MAY 2010) Primary Industries and Water Division 1 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Some comments expressed in this document have arisen out of discussions with marine farmers in the study area and an examination of departmental files. To the best knowledge of the DPIWE, the views of the marine farmers have been correctly incorporated. However, the words describing the operation of each farm in the document are the views of the DPIWE and do not necessarily reflect the views of the operators. Contents Introduction Environmental Impact Statement 2 1.General Introduction 2 2.Characteristics of Great Oyster Bay and Mercury Passage 2 2.1 Geographic Description 2 2.2 Land Description 3 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Human Settlements 9 2.5 Social and Economic Description 9 2.6 Early Oyster Exploitation 12 3 Existing Marine Uses 13 4 Marine Farming in Great Oyster Bay and Mercury Passage Area 17 4.1 Suitability for Marine Farming 17 4.2 Existing Marine Farms 18 4.3 Existing Infrastructure and Service Facilities 24 4.4 Tasmanian Scallops Pty Ltd 24 5 General Impacts of Marine Farming 25 5.1 Ecological Impacts 25 5.2 Visual Impacts 33 5.3 Access Restrictions 34 5.4 Other Impacts 34 5.5 Predicted Impacts of Increased Marine Farming in the Plan Area 35 Development Proposals 36 1 Marine Farming Zones 36 2 Zone Plans 39 Zone 1 (Lachlan Island) 44 Zone 2 (Spring Bay West) 48 Zone 3 (Spring Bay - Horseshoe Shoal) 52