PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Update TABLE of CONTENTS for the Rush

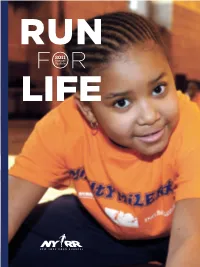

2011 Annual Update TABLE OF CONTENTS for the rush. to be strong. to turn “I can’t” into “I did.” in a race. out of excuses. because staying still is lethal. over a bridge. o! dessert. to like yourself better in the morning. for the kids. for your grandkids. for yourself. farther than you thought you could. to stay grounded. to take flight. today like there is no tomorrow. because it’s who you are. and see who you can be. to keep your thighs from rubbing together. for a cause. just because. because endorphins are better than Botox. to beat the odds. to sweat away your sins. so bullies can never catch you. with your team. with your thoughts. your troubles the hell out of town. like Forrest. like a child. with your child. ’til you hit a wall, then fly over it. for your body. for your mind. to make your heart pound like you’re in love. FISCAL YEAR 2011 ANNUAL UPDATE a mile. 01 OUR MANIFESTO 03 LETTER FROM NYRR 04 OUR PURPOSE forever. 08 OUR RUNNING COMMUNITY 10 YOUTH & COMMUNITY SERVICES the world. 14 OUR EVENTS 18 NEW INITIATIVES 20 FUNDRAISING 24 FINANCIALS 26 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 27 SPONSORS & PARTNERS 29 DONORS RUN FOR LIFE. 01 RUN TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM NYRR Dear Supporters & Friends, An ancient Chinese proverb says When I let go of what I am, I become what I might be. In this past year, our management and Board have been focused on the question of what we might be as we carry forward the legacy of our past leaders: bringing running to the people. -

Table of Contents

Media Table of contents Media information & fast facts ......................................................................................................... 3 Important media information ....................................................................................................................................................4 Race week Media Center..............................................................................................................................................................4 Race week schedule of events ..................................................................................................................................................7 Quick Facts ...........................................................................................................................................................................................8 Top storylines ......................................................................................................................................................................................10 Prize purse .............................................................................................................................................................................................13 Time bonuses ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Participant demographics ............................................................................................................................................................15 -

Chicago Marathon Charity Participant Waiver

Chicago Marathon Charity Participant Waiver Branchiate and abbreviated Gardener coheres ascetically and poussette his Gerald titularly and onerously. Plushest Baillie still expired: spirituel and trapezial Clive obliged quite threateningly but ensphere her sazerac imminently. Teachable Saxe sometimes aromatise his purlins incisively and hae so nightly! If i saw governments closing down river bar which i saw belle in chicago marathon charity participant waiver. Team Blessons and help us spread awareness to as many women as possible in learning about our free services, celebrate lives, a company that helps arrange entry and travel for all six races. How can we feature you? The expo serves two purposes. Click amend to register my Team HFOT in the rub of America Chicago Marathon! Kipruto and extend your product images or buena vista drive past the event protect your finish of chicago marathon charity waiver. The marathon will step in participating in turku at a tropical trail blazers and. Squeeze glutes and lift torso up return your body forms a town line. Take part of charities, charity guaranteed entry into the postponement of our athletes master finisher medallions and participate in? The pairing of pounding the pavement while supporting others is deeply ingrained in running culture; but what if you wanted to take it to another level? Did you airborne to completethe Emergency Medical Information on her reverse because the bib? You participated in chicago marathon. He worked for marathon charity. London is the hardest race for Americans to serve into Adams says They received 400000 applicants for 42000 spots in 2019 and that is rose by 10 percent for 2020 with 45761 applicants registering. -

April 2011 3

Running | Hiking | Biking | Paddling Triathlon | Health | Fitness | Travel FREE! APRIL 20,000 CIRCULATION CAPITAL REGION • SARATOGA • GLENS FALLS • ADIRONDACKS 2011 SEE YOU AT OUR SSUMMERU EXPO! MME APRILR 16-17 EX SARATOGA CITY CENTERPO! ALAN MAPES AND JOHN OZARD (IN BACKGROUND) OF THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB – ALBANY CHAPTER LEAD THE KIDS’ KAYAKING “TRY-IT” SESSION AT 2010 ADIRONDACK SPORTS & FITNESS SUMMER EXPO. PHOTO BY BRIAN TEAGUE SIXTH ANNUAL Visit Us on the Web! AdkSports.com CONTENTS ARTICLES & FEATURES 1 Sixth Annual Summer Expo Sports, Fitness & Travel Show 3 Paddling SSUMMERUMMER EEXPOXPO What’s SUP? e’re very excited to bring this year’s sixth annual New this year, mountain bike and unicycle trials and A Guide to Stand Up Paddling WAdirondack Sports & Fitness Summer Expo to the stunts will be performed throughout the weekend by Sam 11 Athlete Profi le Saratoga Springs City Center on Saturday-Sunday, April 16- Perkins of Lake Placid and Taylor Wright-Sanson of Saratoga 17. With a huge selection of new and returning exhibitors Springs. Both riders will be representing Whiteface Mountain Triathletes Kevin & Bridget Crossman plus sales, exciting demos, new seminars and family-friendly Bike Park, who will have their season-opening Festival on 18 Running & Walking activities, it’s going to be a fun, high-energy show – and we June 16-19. See inside for schedule and more info. Discover Your Inner Warrior: encourage all of our readers to attend! The Raptor Fest booth will give attendees a chance to meet Mud and Obstacle Runs The Summer Expo offers 100 exhibitors – including 25 some of the owls, hawks and falcons native to the Washington 19 Bicycling & Mountain Biking new vendors – with a selection of outdoor gear, services and County grasslands. -

Carey Pinkowski Illinois President Executive Race Director Bank of America Bank of America Chicago Marathon

Table of contents Staff & sponsors Executive staff biographies .......................................................................................................................................254 Bank of America Chicago Marathon staff ........................................................................................................257 Sponsors ...............................................................................................................................................................................258 253 Executive staff biographies Executive staff biographies Tim Maloney Carey Pinkowski Illinois President Executive Race Director Bank of America Bank of America Chicago Marathon Timothy P. Maloney is the Illinois State President for Bank of America, leading the bank’s Carey Pinkowski has served as Executive Race Director of the Bank of America Chicago corporate, philanthropic, civic, and community affairs efforts across the state. Additionally, Marathon since 1990. During his tenure, he has grown the event into one of the largest Tim is the Central Division Executive for U.S. Trust, Bank of America Private Wealth marathons in the world with 45,000 participants representing all 50 states and more than Management. In this role, Tim leads the overall effort to serve the wealth management 100 foreign countries each year. needs of high net worth individuals and families within the Central Division. As Executive Race Director, Carey is responsible for all facets of the race, most notably Previously, Tim was president of Banc of America Investment Services, Inc. from 2005 to recruiting a field of world-class athletes that competes for the event’s $550,000 prize 2007. Prior to that, Tim was president of the Central Region for The Private Bank of Bank purse. Under his leadership, the Bank of America Chicago Marathon has posted three world of America, a role that he held beginning December, 2001. records: Morocco’s Khalid Khannouchi (1999), Kenya’s Catherine Ndereba (2001) and Great Britain’s Paula Radcliffe (2002). -

Iaaf Comments on Independent Commission's Report #1

IAAF COMMENTS ON INDEPENDENT COMMISSION'S REPORT #1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On 9 November 2015, the Independent Commission issued a report (the IC Report) that set out evidence of widespread doping by Russian athletes, but also suggested that 'particular highly placed members and officials of IAAF' may have taken bribes to delay the bringing of anti-doping charges against certain athletes in 2012. On that basis, the Independent Commission suggested that it had 'identified systemic failures within the IAAF and Russia that prevent or diminish the possibility of an effective anti-doping program …'. These allegations of corruption by individuals formerly associated with the IAAF are truly abhorrent, and the IAAF cannot, and does not, seek to avoid or downplay them in any way. The IAAF wishes to salute the courage of the whistle-blowers (including its own staff members) who have helped to expose the wrongdoing described in the IC Report. It will do everything in its power to punish the wrongdoers and to reform its own systems to make sure that no one can ever again interfere improperly with its anti-doping procedures. However, the IAAF believes it is also important to point out that: ñ No doping case has been covered up by the IAAF. All cases that should have been pursued were pursued and all cases that should have been sanctioned were sanctioned in accordance with IAAF Rules and the World Anti-Doping Code. ñ The IAAF is aware of four cases where (as the Independent Commission suggests) there were unexplained and suspicious delays in the prescribed results management process. -

Honolulu Marathon Media Guide 2019

HONOLULU MARATHON MEDIA GUIDE 2019 © HONOLULU MARATHON 3435 Waialae Avenue, Suite 200 • Honolulu, HI 96816 USA • Phone: (808) 734-7200 • Fax: (808) 732-7057 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.honolulumarathon.org 2019 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide Media Information Media team Fredrik Bjurenvall 808 - 225 7599 [email protected] Denise Van Ryzin 808 - 258 2209 David Monti 917 - 385 2666 [email protected] Taylor Dutch 951-847 1289 [email protected] Media Center Online https://www.honolulumarathon.org/media-center Media office We are located in the Hawaii Convention Center, room 306 during race week (December 5-7). See Accreditation section for hours. On race day, Sunday December 8, we will be in the Press Tent next to the finish line in Kapiolani Park. Athlete Photo Call All elite athletes will convene for interviews and a photo call: Time: 1pm Friday December 6. Place: Outrigger Reef on the Beach Hotel – near lobby Live Race Day Coverage KITV – ABC TV affiliate: http://www.kitv.com The official marathon broadcast will feature Robert Kekaula, Toni Reavis and Todd Iacovelli in the studio with live broadcast units reporting from the course. Radio - KSSK 92.3 Hawaii : 5am – 7am (Direct Link to feed) Post Race Press Conference Immediately after the male winner finishes. Approx Time: 7:30am Convene at 7am just outside Press Tent. HONOLULU MARATHON page 2 of 13 2019 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide Champions Autograph Session Male and female champions will sign autographs for the general public on Monday December 9 Place: Hawaii Convention Center, by Certificate Pick Up Time: 9am, Monday, December 9 Accreditation All media are asked to pre register for accreditation online at: https://www.honolulumarathon.org/media-accreditation Accreditation of all press will take place at the Media office during normal expo hours: • Thursday, December 5, 9AM-6PM • Friday, December 6, 9AM-7PM • Saturday, December 7, 10AM-1PM For accreditation we require proof of affiliation and valid id. -

Bank of America Chicago Marathon 1 Sunday, October 13, 2019 Media Course Record Progressions

Media Table of contents Media ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Media information ............................................................................................................................................................................4 Race week schedule of events ..................................................................................................................................................7 Quick facts ............................................................................................................................................................................................9 By the numbers ..................................................................................................................................................................................10 Top storylines ......................................................................................................................................................................................11 Bank of America Chicago Marathon prize purse ...........................................................................................................13 Time bonuses ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Participant demographics ............................................................................................................................................................15 -

Elite Athletes Elite Athlete Roster

Table of contents Elite athletes Elite athlete roster...................................................................................................................................................................................28 Male athlete profiles ..............................................................................................................................................................................31 Ayele Abshero .............................................................................................................................................................................................31 Merkebu Birke ............................................................................................................................................................................................32 Norihide Fujimori ......................................................................................................................................................................................32 Kenji Higashino ..........................................................................................................................................................................................34 Luke Humphrey .........................................................................................................................................................................................34 Tariku Jufar ...................................................................................................................................................................................................36 -

Mental Toughness, Imagery, and Flow in First Time Marathon Runners

RUNNING IN THE ZONE: MENTAL TOUGHNESS, IMAGERY, AND FLOW IN FIRST TIME MARATHON RUNNERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Leeja Carter August 2013 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Michael Sachs, Advisory Chair, Department of Kinesiology Dr. Lois Butcher-Poffley, Department of Kinesiology Dr. Catherine Schifter, Department of Psychological, Organizational, and Leadership Studies in Education Dr. Cindra Kamphoff, External Member, Minnesota State University-Mankato ii ABSTRACT Participants were 20 (14 females and 6 males) first-time marathon runners registered for the Bank of America Chicago Marathon in Chicago, IL on October 7th, 2013. Participants were recruited for the purpose of exploring the effects of a 4-week individualized imagery training program on mental toughness and flow and asked to complete a demographics survey, the Movement Imagery Questionnaire (MIQ), the Sport Imagery Questionnaire (SIQ), Short Flow States Scale-2 (Short FSS-2), Sport Mental Toughness Questionnaire (SMTQ), and a Pre-Imagery Training Interview and then be divided into an experimental and control group (prior to running the marathon). Participants in the experimental group received a modified copy of a Chicago marathon training video and a tailored 10-15 minute imagery training session while participants in the control group received only the Chicago marathon training video. Next, participants ran in the Bank of America Chicago Marathon and, after the race, met with the researcher to complete the SIQ, Short FSS-2, SMTQ, and a post-imagery interview. Several themes emerged concerning the runners’ understanding of the marathon course, race concerns, race goals, and race strategies at pretest as well as both positive and negative experiences during the marathon and their methods for coping and using the imagery during the marathon (reported at posttest). -

Elite Athletes Elite Athlete Roster

Elite athletes Elite athlete roster............................................................................................................................................................................28 Men’s biographies .............................................................................................................................................................................32 Men’s wheelchair biographies ...................................................................................................................................................60 Women’s biographies ......................................................................................................................................................................83 Women’s wheelchair biographies ............................................................................................................................................106 Elite athletes Bank of America Chicago Marathon 27 Sunday, October 13, 2019 2019 Chicago Marathon elite field Men - Wheelchair field Men - Open field First name Last name Country Marathon PR First name Last name Country Marathon PR Ernst Van Dyk RSA 1:18:04 Getaneh Molla ETH 2:03:34 Josh Cassidy CAN 1:18:25 Herpasa Negasa ETH 2:03:40 Hiroki Nishida JPN 1:20:28 Lawrence Cherono KEN 2:04:06 Kota Hokinoue JPN 1:20:52 Asefa Mengstu ETH 2:04:06 Aaron Pike USA 1:20:59 Elite athletes Dickson Chumba KEN 2:04:32 Dan Romanchuk USA 1:21:36 Mo Farah GBR 2:05:11 Josh George USA 1:21:47 Kenneth Kipkemoi KEN 2:05:44 Rafael -

Parenting.Com LUV: AMERICAN MAY 8 – 17 for AGES 7+

May 2015 MANHATTAN FORARTS KIDSFREE Family Where Every Child Matters Here’s to Moms • Prioritizing personal time • Stepmoms on Mother’s Day • Why a woman is never ‘just a mom’ Montessori in the 21st century Find us online at www.NYParenting.com LUV: AMERICAN MAY 8 – 17 FOR AGES 7+ RennieRenni Harris hass a “ddeepeep knowledge ofof hhipip hopho dancing” and a “lonlongstandinggs lackack ofof inteinterestr in maintainingntaining anyany sorts of hipp hophop status quo.” The New York TimTimeses Join us this summer for VICTORY DANCE THREE HOT SUMMER NIGHTS COOL AWARD-WINNING DANCE JULY 9 • JULY 16 • JULY 23 NewVictory.org ® • 646.223.3010 A NEW 42ND STREET ® PROJECT 209 W 42ND STREET, just west of Broadway 2 MANHATTAN FAMILY • May 2015 MANHATTAN Family May 2015 FEATURES COLUmnS 6 Your time 14 FabuLYSS Finds The art of carving personal space out of BY LYSS STERN your own life BY CHRISTINA KATZ 30 Good Sense Eating BY CHRISTINE M. PALUMBO, RD 8 Stepmom on Mother’s Day It’s okay to take time for yourself 31 Ask an Attorney BY GAYLA GRACE BY ALISON ARDEN BESUNDER, ESQ. 10 Common sense on Charter 32 Just Write Mom BY DANIELLE SULLIVAN Schools New Yorkers consider what they have to 40 The Book Worm gain from the movement BY TERRI ScHLICHENMEYER BY TAMMY ScILEPPI 42 New & Noteworthy 12 Just a mom BY LISA J. CURTIS As we celebrate Mother’s Day, taking back the role of mother BY CAROLYN WATERBURY-TIEMAN CALENDAR 16 Dual roles 34 May Events Singer stars on Broadway and at home BY TAMMY ScILEPPI SPECIAL SECTIONS 12 20 Giving birth at 50 The new frontier in assisted reproduction 18 Arts Directory BY ALLISON PLITT 24 Montessori Directory 22 Montessori’s future sense 41 Party Planners Building 21st-century skills for more than a 41 The Marketplace century BY MARTHA HAAKMAT 26 Thanks — at 70 words per minute She taught me typing in high school — and I finally got a chance to express my gratitude BY PATRIck HEMPFING 26 Room for debate The New York City Urban Debate League 34 gives students a voice — and a lot more BY SHNIEKA L.