Exploring Systematics and Phylogenetic Reconstruction Using Biological Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Analysis

BIOL 101L: Principles of Biology Lab Classification & Phylogeny Humans classify almost everything, including each other. This habit can be quite useful. For example, when talking about a car someone might describe it as a 4-door sedan with a fuel injected V-8 engine. A knowledgeable listener who has not seen the car will still have a good idea of what it is like because of certain characteristics it shares with other familiar cars. Humans have been classifying plants and animals for a lot longer than they have been classifying cars, but the principle is much the same. In fact, one of the central problems in biology is the classification of organisms on the basis of shared characteristics. As an example, biologists classify all organisms with a backbone as "vertebrates." In this case the backbone is a characteristic that defines the group. If, in addition to a backbone, an organism has gills and fins it is a fish, a subcategory of the vertebrates. This fish can be further assigned to smaller and smaller categories down to the level of the species. The classification of organisms in this way aids the biologist by bringing order to what would otherwise be a bewildering diversity of species. (There are probably several million species - of which about one million have been named and classified.) The field devoted to the classification of organisms is called taxonomy [Gk. taxis, arrange, put in order + nomos, law]. The modern taxonomic system was devised by Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778). It is a hierarchical system since organisms are grouped into ever more inclusive categories from species up to kingdom. -

Assessing Phylogenetic Accuracy

Assessing Phylogenetic Accuracy A simulation study Theodoor Heijerman CENTRALE LANDBOUW CATALO GU S 0000067 0060 9 Promotor: Dr R. J. Post, hoogleraar in de diertaxonomie fiuoft-iof, \*iQy Assessing Phylogenetic Accuracy A simulation study Theodoor Heijerman Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de landbouw- en milieuwetenschappen op gezag van de rector magnificus, dr C. M. Karssen, in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 27 september 1995 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen 0 SVI a1 (H>^ LA2\!ï>(JüL",VLK'V;:F.>i^lïiT YY*/.-::^- i-'.N CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Heijerman, Theodoor Assessing phylogenetic accuracy : a simulation study / Theodoor Heijerman. - [S.I. : s.n.] (Wageningen : Ponsen & Looijen) Thesis Landbouw Universiteit Wageningen. - With réf. - With summary in Dutch. ISBN 90-5485-422-7 Subject headings: phylogenesis / animal taxonomy. Cover: 'n kroezen boom Stellingen Het getuigt van te veel optimisme ten aanzien van het prestatievermogen van numeriek taxonomische methoden, wanneer deze worden aangeduid als fylogenie-reconstructie-methoden. (dit proefschrift; F. J. Rohlf & M. C. Wooten, 1988. Evaluation of the restricted maximum-likelihood method for estimating phylogenetic trees using simulated allele-frequency data. — Evolution 42: 581-595). Het beschikbaar komen van steeds gebruikersvriendelijker programma's voor cladistische analyses, zal de gemiddelde kwaliteit van de resultaten van deze programma's doen afnemen. Het is sterk aan te bevelen om bij de presentatie van de resultaten van een cladistische analyse, niet alleen de meest parsimone, maar ook sub-optimale oplossingen te geven. De toepassing van fenetische technieken om verwantschapsrelaties te bepalen, is ten onrechte in onbruik geraakt. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Caminalcules. I

Society of Systematic Biologists A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Caminalcules. I. The Data Base Author(s): Robert R. Sokal Source: Systematic Zoology, Vol. 32, No. 2 (Jun., 1983), pp. 159-184 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. for the Society of Systematic Biologists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2413279 . Accessed: 26/01/2015 14:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and Society of Systematic Biologists are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Systematic Zoology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.101.61.40 on Mon, 26 Jan 2015 14:41:44 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Syst.Zool., 32(2):159-184, 1983 A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE CAMINALCULES. L. THE DATA BASE ROBERT R. SOKAL Departmentof Ecologyand Evolution,State Universityof New Yorkat StonyBrook, StonyBrook, New York 11794 Abstract.-The Caminalcules are a group of "organisms" generated artificiallyaccording to principles believed to resemble those operating in real organisms. A reanalysis of an earlier data matrixof the Caminalcules revealed some inconsistencies and errorswhich necessitated recoding of some characters.The resultingdifferences with earlier resultsare minor.The images of all 77 Caminalcules are featured,those of the 48 fossilspecies forthe firsttime. -

Lecture 11: Phylogenetic Tree Inference: Introduction Evolution

Evolution: inheritance and mutation COSC 348: Computing for Bioinformatics • Organisms (animals or plants) produce a number of offspring which are almost, but not entirely, Lecture 11: like themselves: – Variation is due to sexual Phylogenetic tree inference: introduction reproduction (offspring have some characteristics from each parent, alleles from 2 parents Lubica Benuskova combine randomly) Prepared according to the notes of Dr. Richard O’Keefe – In addition, variation is due to mutation (random changes) in the fertilised egg. http://www.cs.otago.ac.nz/cosc348/ 1 2 Evolution: natural selection Mutations drive evolution • If a mutation happens in the DNA of a fertilised • Some of these offspring survive egg, then all the cells of an offspring carry this to produce offspring of their mutation because this mutation is replicated by DNA replication during cell division. own—some won’t: – The offspring with bigger • If that offspring survives, every offspring of his fitness are more likely to own will carry the same mutation. That’s how survive and reproduce mutations are preserved over evolution. – Over time, later generations become better and better • Mutations that result in an improved trait, drive evolution. adapted to a given – E.g., bigger claws, better eyesight, opposing environment because only the thumb, bigger brains, etc. fittest individuals have a higher chance to survive and Charles Darwin • Mutations that accumulate over time lead to reproduce. appearance of new species through intermediate 4 3 forms. What is a phylogeny? Basic terms from dictionary • A phylogeny is a tree showing • Taxonomy: The classification of items in an ordered system ancestor/descendant relationships that indicates natural relationships. -

Pre-Lab Homework Lab 9: Tracing Phylogeny

Biology 102 PCC - Cascade Lab Section: ____________________ Name: ______________________________________ Pre-lab Homework Lab 9: Tracing Phylogeny 1. What are the 3 domains and 6 kingdoms of living organisms? 2. Define the following terms in your own words : • Phylogeny: • Taxonomy: • Derived trait: 2. Figure 14.16 in your text shows how structural differences can be used to determine evolutionary relationships. Structures that developed from a common ancestor are called homologous structures . One difficulty in identifying homologous structures is that sometimes structures are similar but are not due to common ancestry. These are analogous structures. What are analogous structures and why do they occur? 3. Upon comparing sharks and dolphins you notice that both have dorsal fins that stick up out of their backs. Do you think these dorsal fins are homologous or analogous? Why? Recall: dolphins are mammals like us. 1 Biology 102 PCC - Cascade 2 Biology 102 PCC - Cascade Name: _______________________________________ Date/Lab time: ___________________ Lab 9: Tracing Phylogeny LAB SYNOPSIS: • We will develop a taxonomic classification and phylogenetic tree for a group of imaginary organisms called Caminalcules . • We will construct a phylogenetic tree of vertebrates from data given. • We will be answering questions while watching a video on the evolution of whales. OBJECTIVES: After successfully completing this lab, a student will be able to: • Explain the connection between an organism’s taxonomy and its evolutionary history. • Describe the process used to develop evolutionary trees. • Distinguish between analogy and homology when examining traits on evolutionary trees. This exercise is modified from that of Robert P. Gendron, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. -

Systematics and Taxonomy by Dana Krempels and Julian Lee

Evolution and Biodiversity Laboratory Systematics and Taxonomy by Dana Krempels and Julian Lee Recent estimates of our planet's biological diversity suggest that the species number between 5 and 50 million, or even more. To effectively study the myriad organisms that inhabit the biosphere, we attempt to classify organisms into groups that reflect evolutionary relationships. I. Taxonomy Strictly speaking, taxonomy is the science of sorting and classifying living organisms into groups called taxa (singular = taxon). Taxonomy also includes describing and naming the members of those taxa. A scientist who engages in taxonomy is a taxonomist. A taxon is a group of organisms that a taxonomist has judged to represent a cohesive unit. The criteria used to sort specimens into various taxa are not fixed, and the science of taxonomy is not without its internal controversies. Taxonomists often distinguish between natural and artificial taxa. A natural taxon is constructed on the basis of evolutionary relationships. While not all taxonomists insist that taxa be natural, most believe that taxonomic groups should consist of evolutionarily related units. The science of determining evolutionary relationships among taxa is known as systematics, and its practitioners are systematists. (Most systematists are also taxonomists, and vice versa.) Since systematists are concerned not only with the ability to sort and identify organisms, but also with determining their evolutionary relationships, taxonomy is used as a tool within systematics. Biological nomenclature is the application of names to organisms recognized as part of a particular taxon. From most to least inclusive, the major taxonomic ranks are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1. -

Activity: Constructing a Phylogeny by Dana Krempels and Julian Lee

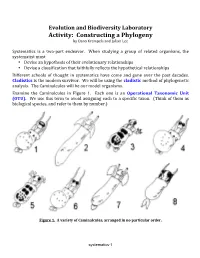

Evolution and Biodiversity Laboratory Activity: Constructing a Phylogeny by Dana Krempels and Julian Lee Systematics is a two-part endeavor. When studying a group of related organisms, the systematist must • Devise an hypothesis of their evolutionary relationships • Devise a classification that faithfully reflects the hypothetical relationships Different schools of thought in systematics have come and gone over the past decades. Cladistics is the modern survivor. We will be using the cladistic method of phylogenetic analysis. The Caminalcules will be our model organisms. Examine the Caminalcules in Figure 1. Each one is an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU). We use this term to avoid assigning each to a specific taxon. (Think of them as biological species, and refer to them by number.) Figure 1. A variety of Caminalcules, arranged in no particular order. systematics-1 I. Example: Using Synapomorphies to Construct a Phylogeny OTUs are grouped together on the basis of synapomorphies. The presence (or absence) of a synapomorphy in two or more OTUs is inferred to be the result of common ancestry. Results of a cladistic analysis are summarized in a phylogenetic tree called a cladogram (from the Greek clad meaning "branch"), an explicit hypothesis of evolutionary relationships. Following is an example of how to create a cladogram of our Figure 1 OTUs. Step One. Select a series of binary (i.e., two-state) characters. For example: character a: "eyes present" (+) versus "eyes absent" (-) character b: "body mantle present" (+) versus "body mantle absent" (-) character c: "paired, anterior non-jointed appendages present" (+) versus "paired, anterior non-jointed appendages not present" (-) character d: "anterior appendages flipperlike" (+) versus "anterior appendages not flipperlike" (-) character e: "eyes stalked" (+) versus "eyes not stalked" (-) character f: "body mantle posterior bulbous" (+) versus "body mantle posterior not bulbous" (-) character g: "eyes fused into one" (+) versus "eyes separate" (-) character h. -

Willi Henning's Impact on Taxonomic Thought

Annual Reviews www.annualreviews.org/aronline by CAPES on 03/19/09. For personal use only. Willi Hennig (1913-1976) in his fifties. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984.15:1-25. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org Annual Reviews www.annualreviews.org/aronline Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984. 15:1-24 Copyright@ 1984 by AnnualReviews lnc, All rights reserved WILLI HENNIG’S IMPACT ON TAXONOMIC THOUGHT C. Dupuis MusrumNational d’Histoire Naturelle et l~cole Pratique des Hautesl~tudes, 75005 Paris, France The present review is neither bibliographical nor historical. I hope merely to overview the methodological strengths and weaknessesof Hennigian taxonom- ical thought and of somerecent worksdevoted to theoretical questions that have been revived by an increasing interest in that thought. A FASCINATING EPISTEMOLOGICAL VENTURE Willi Hennig (1913-1976) was a Germaninsect taxonomist who was known during his life time amongDiptera specialists for numerous monographs by CAPES on 03/19/09. For personal use only. assignable at first sight to alpha systematics (100). Althoughhe published major work on theoretical taxonomy in Germanas early as 1950 (74), becamefamous only after the publication in 1966of the English translation of a second book (77), which was not published in its original languageuntil 1982 (82). Initially, his workengendered fierce attacks on his "phylogenetic sys- tematics" by membersof other taxonomic schools (41). Recently, however, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984.15:1-25. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org Hennig’s ideas have cometo form the foundation of the fashionable cladistic school. The epistemological analysis of this venture will be a task for the future, provided that the original worksare not forgotten. -

Exploring Systematics and Phylogenetic Reconstruction Using Biological Models

Tested Studies for Laboratory Teaching Proceedings of the Association for Biology Laboratory Education Vol. 33, 123-144, 2012 Exploring Systematics and Phylogenetic Reconstruction Using Biological Models Hans Lemke and Jeffrey Jensen Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 ([email protected], [email protected]) Systematics and phylogenetic reconstructions are among the most difficult concepts for students to understand in introductory biology. They are also fundamental to understanding how biologists view the evolutionary history of the world around us. This exercise uses models of Caminalcules to teach basic tree construction and interpretation. Students first construct a tree of by hand, and then they then use the computer program Mesquite to construct and analyze a more complex tree. Keywords: Phylogenetics, Systematics, Tree Thinking, Caminalcules, Mesquite, Teaching Models, Mold Making Introduction Tree thinking is one of the most fundamental concepts construction of a tree. With that in mind, the exercise takes needed to understand evolutionary theory. This lab exercise the students step-by-step through the processes of creating uses models to provide students with a basic knowledge and and interpreting trees. The students use 3D models of five understanding of systematics and phylogenetic reconstruc- species of Caminalcules (imaginary organisms) to first build tion. It is designed for use in an introductory biology course a tree by hand. They then use the computer program Mes- for majors. For most first-year students, this will be their ini- quite to build a more complex tree with 10 species. For both tial exposure to these techniques and ideas. In our course, of these exercises, there are questions to help students inter- the lecture and lab are tightly integrated and the basics of pret their trees. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Caminalcules. I. the Data Base Author(S): Robert R

Society of Systematic Biologists A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Caminalcules. I. The Data Base Author(s): Robert R. Sokal Reviewed work(s): Source: Systematic Zoology, Vol. 32, No. 2 (Jun., 1983), pp. 159-184 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. for the Society of Systematic Biologists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2413279 . Accessed: 02/04/2012 22:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and Society of Systematic Biologists are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Systematic Zoology. http://www.jstor.org Syst.Zool., 32(2):159-184, 1983 A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE CAMINALCULES. L. THE DATA BASE ROBERT R. SOKAL Departmentof Ecologyand Evolution,State Universityof New Yorkat StonyBrook, StonyBrook, New York 11794 Abstract.-The Caminalcules are a group of "organisms" generated artificiallyaccording to principles believed to resemble those operating in real organisms. A reanalysis of an earlier data matrixof the Caminalcules revealed some inconsistencies and errorswhich necessitated recoding of some characters.The resultingdifferences with earlier resultsare minor.The images of all 77 Caminalcules are featured,those of the 48 fossilspecies forthe firsttime. The characters of the Caminalcules are defined and a data matrixis furnishedfor all Recent and fossil species. -

Parsimony.Pdf

Parsimony (and a little bit of the history of phylogenetics) Paul O. Lewis ~ Phylogenetics, Spring 2020 Cladistics 1950: Willi Hennig published Grundzüge einer Theorie der Phylogenetischen Systematik, which was later (1966) fly frog human translated into English as Phylogenetic Systematics. - - Emphasized that phylogenetic groups should be defined on vertebrae the basis of shared, derived characters (synapomorphies), not on the basis of shared, ancestral characters (symplesiomorphies) fern lily moss Although widely considered to be the father of cladistics, Hennig never described an algorithm based on the parsimony criterion, nor did he suggest what to do in the case of character conflict. ⑤vascular tissues Hennig, W. 1966. Phylogenetic systematics. University of Illinois Press, Urbana Photo: Frontispiece of Wiley, E. O. 1981. Phylogenetics: the theory and practice of Paul O. Lewis ~ Phylogenetics, Spring 2020 phylogenetic systematics. John Wiley & Sons, New York. Photo by George W. Byers, Univ. Kansas Changing terminology Oglabrous Otomentose glabrous tomentose tomentose tomentose Transformation series: Character: leaf pubescence leaf pubescence Characters: Character states: glabrous glabrous IEtomentose # tomentose Photo (tomentose): http://www.sbs.utexas.edu/bio406d/images/pics/eup/croton_capitatus.htm Paul O. Lewis ~ Phylogenetics, Spring 2020 Photo (glabrous): http://www.lhccrems.nsw.gov.au/CPR/CPR/glossary/glabrous.htm First computed phylogeny 1957: Charles Michener and o s Robert Sokal published the first phylogeny estimated using a computer (but not using parsimony). Robert Sokal, 1959 “...the computation of a 97 species X 97 species matrix of correlation coefficients presents serious technical difficulties. An operation of this magnitude cannot be reasonably undertaken without punched card or electronic computing equipment.”- - Michener, C. -

Constructing Student Problems in Phylogenetic Tree Construction

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 227 SE 059 945 AUTHOR Brewer, Steven D. TITLE Constructing Student Problems in Phylogenetic Tree Construction. PUB DATE Mar 97 NOTE 33p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Chicago, IL, March 24-28, 1997). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biology; *Concept Teaching; *Evolution; Fundamental Concepts; Higher Education; Instructional Development; Knowledge Base for Teaching; Models; *Problem Solving; Schematic Studies; Science Education; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Phylogenetics ABSTRACT Evolution is often equated with natural selection and is taught from a primarily functional perspective while comparative and historical approaches, which are critical for developing an appreciation of the power of evolutionary theory, are often neglected. This report describes a study of expert problem-solving in phylogenetic tree construction. Results from that study are then used to describe problems in this domain and factors that govern problem difficulty. A problem-based approach to the teaching and learning of evolution was considered. Three series of research problems were constructed that varied the numbers of solutions, taxa, and characters. Each problem consisted of a matrix of coded and polarized phylogenetic data organized by taxa and characters. Nine expert phylogenetic systematists participated in the research project by thinking aloud while constructing phylogenetic trees to account for the problem data matrices. All of the experts agreed that the problems were a realistic characterization of the concepts and processes central to their discipline. Simple tree construction problems such as these allow students to become familiar with the processes used by scientists to explain evolutionary history.