Steve Clark and David Worrall, Eds., Blake in the Nineties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Introduction

Introduction The notes which follow are intended for study and revision of a selection of Blake's poems. About the poet William Blake was born on 28 November 1757, and died on 12 August 1827. He spent his life largely in London, save for the years 1800 to 1803, when he lived in a cottage at Felpham, near the seaside town of Bognor, in Sussex. In 1767 he began to attend Henry Pars's drawing school in the Strand. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver, making plates from which pictures for books were printed. He later went to the Royal Academy, and at 22, he was employed as an engraver to a bookseller and publisher. When he was nearly 25, Blake married Catherine Bouchier. They had no children but were happily married for almost 45 years. In 1784, a year after he published his first volume of poems, Blake set up his own engraving business. Many of Blake's best poems are found in two collections: Songs of Innocence (1789) to which was added, in 1794, the Songs of Experience (unlike the earlier work, never published on its own). The complete 1794 collection was called Songs of Innocence and Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. Broadly speaking the collections look at human nature and society in optimistic and pessimistic terms, respectively - and Blake thinks that you need both sides to see the whole truth. Blake had very firm ideas about how his poems should appear. Although spelling was not as standardised in print as it is today, Blake was writing some time after the publication of Dr. -

The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake's Poetry

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry Audrey F. Lytle Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation Lytle, Audrey F., "The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1026. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1026 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~ THE AMBIGUITY OF "WEEPING" IN WILLIAM BLAKE'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Audrey F. Lytle August, 1968 LD S77/3 I <j-Ci( I-. I>::>~ SPECIAL COLL£crtoN 172428 Library Central W ashingtoft State Conege Ellensburg, Washington APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ H. L. Anshutz, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Robert Benton _________________________________ John N. Terrey TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 Method 1 Review of the Literature 4 II. "WEEPING" IMAGERY IN SELECTED WORKS 10 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10 Songs of Innocence 11 --------The Book of Thel 21 Songs of Experience 22 Poems from the Pickering Manuscript 30 Jerusalem . 39 III. CONCLUSION 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 APPENDIX 58 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I. -

Blake's Portrayal of Women

ARTICLE Blake’s Portrayal of Women Anne K. Mellor Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, pp. 148-155 PAGH 148 BLAKt. AS lU.USIRMlD QllARIh.Rl.) WINTHR 1982-83 Blake's Portrayal of Women BY ANNE K. MELLOR In Eden or Eternity, as Los says m Jerusalem, the human fallen world of Experience and try to redeem it. The more form divine is both male and female: courageous Oothoon lacks the power to break her lover's or her society's mind-forged manacles; thus she is, despite her When in Eternity Man converses with Man they enter liberated vision, an impotent revolutionary. Ololon, how- Into each others Bosom (which are Universes of delight) ever eager she is to give up her virginity and to unite with In mutual interchange, . Milton, remains a submissive Eve. And Jerusalem can only For Man cannot unite with Man but by their Emanations wait patiently for Albion to acknowledge her love and em- Which stand both Male & Female at the Gates of each Humanity brace her; her redemptive role in the poem is circumscribed (788:3-5, 9-10; E 244) by male choices and responses. Blake's attack on domineering women —on Rahab, Tirzah, Vala, Leutha, the Enitharmon Focusing on such lines as these, critics have hailed Blake as of Europe, and all those women whom he denounces as em- an advocate of androgyny, of a society in which there is total bodiments of the "Female Will" — is oven and repetitive. In a sexual equality. Irene Tayler has acclaimed Blake's revolu- typical passage, Los urges Albion to rebel against the power of tionary attack on the limited sex-roles of a patriarchal culture the female: and emphasized that in Blake's liberated Eternity, "there are no sexes, only Human Forms,"1 forms that experience no . -

The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence

Colby Quarterly Volume 25 Issue 1 March Article 3 March 1989 Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence Deborah Guth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 25, no.1, March 1989, p.4-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Guth: Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innoc Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence by DEBORAH GUTH T IS one of the axioms of Blake criticism that the two "Contrary States I of the Human Soul," Innocence and Experience, are portrayed separately through the sets of songs bearing their respective names. The Songs ofInnocence, rendered through lilting childlike rhymes, dramatize the enchanted inner world of the child; 1 the following series defines the spiritual landscape of its absence, while critical distance, mutual ex posure, and satire are achieved through the juxtaposition of the two sets of songs within a single composite work (Frye, 237; Bloom, Vis. Co., 34). However, although the Songs ofInnocence are apparently intended for children- "Every child may joy to hear"- closer analysis reveals, within this series alone, complex levels of discourse which are alien to the child's world as well as implied situations and conflicting emotions glimpsed by Innocence but properly belonging to the world of Experience. Most significantly, although the stated purpose of these songs is to portray the state of Innocence, almost all contain forebodings and insights from the world ofExperience which subliminally call on the reader to focus beyond the halcyon world of joy and faith which is their ostensible subject. -

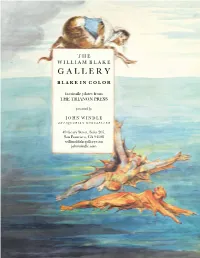

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Microfilms Internationa! 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Title/Author: the Spider and the Fly by Mary Howitt with Illustrations by Tony Diterlizzi

Students Achievement Partners Sample The Spider and The Fly Recommended for Grade 1 Title/Author: The Spider and The Fly by Mary Howitt with illustrations by Tony DiTerlizzi Suggested Time: 5 Days (five 20-minute sessions) Common Core grade-level ELA/Literacy Standards: RI.1.1, RI.1.2, RI.1.4, RI.1.6, RI.1.7; W.1.2, W.1.8; SL1.1, SL.1.2, SL.1.5; L.1.4 Lesson Objective: Students will listen to an illustrated narrative poem read aloud and use literacy skills (reading, writing, discussion and listening) to understand the central message of the poem. Teacher Instructions: Before the Lesson: 1. Read the Key Understandings and the Synopsis below. Please do not read this to the students. This is a description to help you prepare to teach the book and be clear about what you want your children to take away from the work. Key Understandings: How does the Spider trick the Fly into his web? The Spider uses flattery to trick the Fly into his web. What is this story trying to teach us? Don’t let yourself be tricked by sweet, flattering words. Page 1 of 16 Students Achievement Partners Sample The Spider and The Fly Recommended for Grade 1 Synopsis This is an illustrated version of the well-known poem about a cunning spider and a little fly. The Spider tries to lure the Fly into his web, promising interesting things to see, a comfortable bed, and treats from his pantry. At first the Fly, who has been told it is dangerous to go into the Spider’s parlor, refuses. -

THE ART and ARGUMENT of "THE TYGER" Author(S): John E

THE ART AND ARGUMENT OF "THE TYGER" Author(s): John E. Grant Source: Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 1960), pp. 38-60 Published by: University of Texas Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40753660 Accessed: 29-08-2016 20:11 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Texas Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Texas Studies in Literature and Language This content downloaded from 132.236.27.217 on Mon, 29 Aug 2016 20:11:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE ART AND ARGUMENT OF "THE TYGER" By John E. Grant I. The Poem Blake's "The Tyger" is both the most famous of his poems and one of the most enigmatic. It is remarkable, considering its popularity, that there is no single study of the poem which is not marred by inaccuracy or inattention to crucial details. Partly as a result, the two most recent popular interpretations of "The Tyger" are very uneven in quality.1 Another reason that the meaning of the poem has been only partially revealed is that the textual basis for interpretation is insecure. -

The Four Zoas Vala

THE FOUR ZOAS The torments of Love & Jealousy in The Death and Judgement of Albion the Ancient Man by William Blake 1797 Rest before Labour For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. (Ephesians 6: 12; King James version) VALA Night the First The Song of the Aged Mother which shook the heavens with wrath Hearing the march of long resounding strong heroic Verse Marshalld in order for the day of Intellectual Battle Four Mighty Ones are in every Man; a Perfect Unity John XVII c. 21 & 22 & 23 v Cannot Exist. but from the Universal Brotherhood of Eden John I c. 14. v The Universal Man. To Whom be Glory Evermore Amen και. εςηνωςεν. ηµιν [What] are the Natures of those Living Creatures the Heavenly Father only [Knoweth] no Individual [Knoweth nor] Can know in all Eternity Los was the fourth immortal starry one, & in the Earth Of a bright Universe Empery attended day & night Days & nights of revolving joy, Urthona was his name In Eden; in the Auricular Nerves of Human life Which is the Earth of Eden, he his Emanations propagated Fairies of Albion afterwards Gods of the Heathen, Daughter of Beulah Sing His fall into Division & his Resurrection to Unity His fall into the Generation of Decay & Death & his Regeneration by the Resurrection from the dead Begin with Tharmas Parent power. darkning in the West Lost! Lost! Lost! are my Emanations Enion O Enion We are become a Victim to the Living We hide in secret I have hidden Jerusalem in Silent Contrition O Pity Me I will build thee a Labyrinth also O pity me O Enion Why hast thou taken sweet Jerusalem from my inmost Soul Let her Lay secret in the Soft recess of darkness & silence It is not Love I bear to [Jerusalem] It is Pity She hath taken refuge in my bosom & I cannot cast her out. -

William Blake (1757-1827)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN William Blake (1757-1827) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Contents General Editor’s Preface x A Note on Editions xi PART 1: ANALYSING WILLIAM BLAKE’S POETRY Introduction 3 The Scope of this Volume 3 Analysing Metre 3 Blake’s Engraved Plates 6 1 Innocence and Experience 9 ‘Introduction’ (Songs of Innocence)9 ‘The Shepherd’ 15 ‘Introduction’ (Songs of Experience)17 ‘Earth’s Answer’ 23 The Designs 30 Conclusions 42 Methods of Analysis 45 Suggested Work 47 2 Nature in Innocence and Experience 50 ‘Night’ 51 ‘The Fly’ 59 ‘The Angel’ 62 ‘The Little Boy Lost’ and ‘The Little Boy Found’ 64 ‘The Little Girl Lost’ and ‘The Little Girl Found’ 68 ‘The Lamb’ 80 ‘The Tyger’ 82 Summary Discussion 91 Nature in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 93 Conclusions 102 Methods of Analysis 104 Suggested Work 105 vii viii Contents 3 Society and its Ills 107 ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ (Songs of Innocence) 107 ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ (Songs of Experience) 113 ‘Holy Thursday’ (Songs of Innocence) 117 ‘Holy Thursday’ (Songs of Experience) 118 ‘The Garden of Love’ 121 ‘London’ 125 Toward the Prophetic Books 130 The Prophetic Books 134 Europe: A Prophecy 134 The First Book of Urizen 149 Concluding Discussion 154 Methods of Analysis 157 Suggested Work 160 4 Sexuality, the Selfhood and Self-Annihilation 161 ‘The Blossom’ and ‘The Sick Rose’ 161 ‘A Poison Tree’ 166 ‘My Pretty Rose Tree’ 170 ‘The Clod & the Pebble’ 173 Selfhood and Self-Annilhilation in the Prophetic Books 177 The Book of Thel 178 The First Book of Urizen 182 Milton, A Poem 187 Suggested Work 192 PART 2: THE CONTEXT AND THE CRITICS 5 Blake’s Life and Works 197 Blake’s Life 197 Blake’s Works 206 Blake in English Literature 209 Blake as a ‘Romantic’ Poet 210 6 A Sample of Critical Views 220 General Remarks 220 Northrop Frye and David V.