1.Edge Effects and Exterior Influences on Bukit Timah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autecology of the Sunda Pangolin (Manis Javanica) in Singapore

AUTECOLOGY OF THE SUNDA PANGOLIN (MANIS JAVANICA) IN SINGAPORE LIM T-LON, NORMAN (B.Sc. (Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2007 An adult male Manis javanica (MJ17) raiding an arboreal Oceophylla smaradgina nest. By shutting its nostrils and eyes, the Sunda Pangolin is able to protect its vulnerable parts from the powerful bites of this ant speces. The scales and thick skin further reduce the impacts of the ants’ attack. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My supervisor Professor Peter Ng Kee Lin is a wonderful mentor who provides the perfect combination of support and freedom that every graduate student should have. Despite his busy schedule, he always makes time for his students and provides the appropriate advice needed. His insightful comments and innovative ideas never fail to impress and inspire me throughout my entire time in the University. Lastly, I am most grateful to Prof. Ng for seeing promise in me and accepting me into the family of the Systematics and Ecology Laboratory. I would also like to thank Benjamin Lee for introducing me to the subject of pangolins, and subsequently introducing me to Melvin Gumal. They have guided me along tremendously during the preliminary phase of the project and provided wonderful comments throughout the entire course. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) provided funding to undertake this research. In addition, field biologists from the various WCS offices in Southeast Asia have helped tremendously throughout the project, especially Anthony Lynam who has taken time off to conduct a camera-trapping workshop. -

2 Parks & Waterbodies Plan

SG1 Parks & Waterbodies Plan AND IDENTITY PLAN S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 SG1 i 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Parks & Waterbodies Plan and the Identity Plan present ideas and possibilities on how we can enhance our living environment by making the most of our natural assets like the greenery and waterbodies and by retaining places with local identity and history. The two plans were put to public consultation from 23 July 2002 to 22 October 2002. More than 35,000 visited the exhibition, and feedback was received from about 3,600 individuals. Appointment of Subject Groups 1.2 3 Subject Groups (SGs) were appointed by Minister of National Development, Mr Mah Bow Tan as part of the public consultation exercise to study proposals under the following areas: a. Subject Group 1: Parks and Waterbodies Plan and the Rustic Coast b. Subject Group 2: Urban Villages and Southern Ridges & Hillside Villages c. Subject Group 3: Old World Charm 1.3 The SG members, comprising professionals, representatives from interest groups and lay people were tasked to study the various proposals for the 2 plans, conduct dialogue sessions with stakeholders and consider public feedback, before making their recommendations to URA on the proposals. Following from the public consultation exercise, URA will finalise the proposals and incorporate the major land use changes and ideas into the Master Plan 2003. -

Signature Homes by Hiaphoe FY 2010 Calendar of Events January to December 2010

HIAP HOE LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Signature Homes by HiapHoe FY 2010 Calendar of Events January to December 2010 20 January Temporary Occupation Permit obtained for Oxford Suites 28 January Wyndham Group to Operate Hiap Hoe-SuperBowl Hotels at Zhongshan Park in Balestier 11 February 2009 Full Year Financial Statement and Dividend Announcement 26 February Temporary Occupation Permit obtained for Cuscaden Royale 3 March Hiap Hoe Launches Home Resort at Cavenagh 17 March Change of name of wholly-owned subsidiary, Siong Hoe Development Pte Ltd to Hiap Hoe Investment Pte. Ltd. 24 March Listing and quotation of 94,911,028 Bonus Shares 20 April Annual General Meeting / Extraordinary General Meeting 12 May First Quarter Financial Statement Announcement 13 August Second Quarter Financial Statement Announcement 9 November Third Quarter Financial Statement and Dividend Announcement 25 November Book Closure Date - Interim Dividend of 0.25 cents per ordinary share Contents 01 Vision, Mission, Value Corporate Profile 02 Group Structure 03 Financial Highlights 04 Chairman’s Message 06 Financial Review 08 Operations Review 14 Board of Directors 16 Key Management 17 Corporate Information 18 Risk Management For a better understanding of the Annual Report and overall profile of the Company, shareholders are encouraged to download the SGX’s Investor’s Guide Books via this link, http://www.sgx.com/wps/portal/marketplace/mp-en/investor_centre/investor_guide. For more information on the Group, please visit www.hiaphoe.com Vision, Mission, Values A RICHER LIFE FOR each OF US Be a competitive market player in residential properties, bringing reward and satisfaction to shareholders, customers, associates and employees We prize foresight, integrity and commitment among other time- honoured values Company Profile The Hiap Hoe Group has more than three decades of experience in construction industry, and has been responsible for a large and varied number of projects in Singapore. -

The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Seriesdraws On

Biodiversity: Nature Conservation in the Greening of Singapore - In a small city-state where land is considered a scarce resource, the tension between urban development and biodiversity conservation, which often involves protecting areas of forest from being cleared for development, has always been present. In the years immediately after independence, the Singapore government was more focused on bread-and-butter issues. Biodiversity conservation was generally not high on its list of priorities. More recently, however, the issue of biodiversity conservation has become more prominent in Singapore, both for the government and its citizens. This has predominantly been influenced by regional and international events and trends which have increasingly emphasised the need for countries to show that they are being responsible global citizens in the area of environmental protection. This study documents the evolution of Singapore’s biodiversity conservation efforts and the on-going paradigm shifts in biodiversity conservation as Singapore moves from a Garden City to a City in a Garden. The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Series draws on original Urban Systems Studies research by the Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore (CLC) into Singapore’s development over the last half-century. The series is organised around domains such as water, transport, housing, planning, industry and the environment. Developed in close collaboration with relevant government agencies and drawing on exclusive interviews with pioneer leaders, these practitioner-centric booklets present a succinct overview and key principles of Singapore’s development model. Important events, policies, institutions, and laws are also summarised in concise annexes. The booklets are used as course material in CLC’s Leaders in Urban Governance Programme. -

Sustainability of an Urban Forest: Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Singapore

7 Sustainability of an Urban Forest: Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Singapore Kalyani Chatterjea National Institute of Education Nanyang Technological University Singapore 1. Introduction Singapore, an island republic, is situated south of the Malay Peninsula, between 1º09´N and 1º29´N and longitudes 103º38´E and 104º06´E. The main island and 60 small islets cover an area of about 710.2 sq km and support a humid tropical type of vegetation. At the time of the founding of modern Singapore in 1819, practically the whole of the main island was forest covered. Land clearance for development was done in massive scale during the colonial times. After the first forest reserves were set up in 1883, efforts to conserve parts of the forested areas have evolved. In 1951 legal protection was given to Bukit Timah, Pandan, Labrador and the water catchment areas. When Singapore became an independent state in1965, there were five nature reserves in all (Wee & Corlett, 1986). Since its independence in 1965, in an effort to develop its economy and infrastructure, Singapore has continued to clear forests to provide land for industries, residential use, military purposes, and infrastructure. With one of the highest population densities in the world, pressure on land is the driving force that has influenced the extents of the forests. But Singapore has managed to provide legal protection to retain some land as reserve forests. Till the 90’s nature conservation was a mere governmental task to maintain the forested areas of the island. About 4.5% of the total land area is given to forests and there are a total of four protected nature reserves in Singapore. -

Cross Island Line

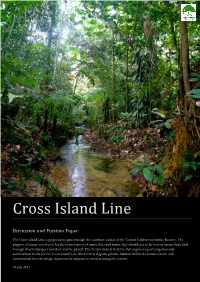

Cross Island Line Discussion and Position Paper The Cross Island Line is proposed to pass through the southern section of the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. The purpose of nature reserves is for the conservation of native flora and fauna, they should not to be seen as vacant State land through which transport corridors may be placed. The Nature Society believes that engineering investigation and construction works for the Cross Island Line will severely degrade pristine habitats within the nature reserve and recommends that the design alignment be adjusted to avoid crossing the reserve. 18 July 2013 NSS Discussion & Position Paper - Cross Island Line Front cover: Rainforest stream within the MacRitchie Forest. 1 Nature Society (Singapore) NSS Discussion & Position Paper - Cross Island Line Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 CROSS-ISLAND LINE PROPOSAL .......................................................................................................................................... 4 3 NSS POSITION AND REASONING ........................................................................................................................................ 5 4 GEOGRAPHY AND BIODIVERSITY OF THE CENTRAL NATURE RESERVES .............................................................................. 6 4.1 LAND DEVELOPMENT AND HABITAT LOSS ON SINGAPORE ISLAND ................................................................................................... -

Re-Imagining Urban Movement in Singapore: at the Intersection Between a Nature Reserve, an Underground Railway and an Eco-Bridge

Cultural Studies GENERAL ARTICLE Review Re-Imagining Urban Movement in Singapore: Vol. 25, No. 2 At the Intersection Between a Nature Reserve, December 2019 an Underground Railway and an Eco-Bridge Jamie Wang University of Sydney Corresponding author: Jamie Wang: School of Philosophy and Historical Inquiry, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney, [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v25i2.6213 Article history: Received 23/07/2018; Revised 21/10/2019; Accepted 25/10/19; Published © 2019 by the author(s). This 22/11/2019 is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Abstract (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ In 2013, the Singapore government announced a plan to build the Cross Island Line (CRL), by/4.0/), allowing third parties the country’s eighth Mass Rapid Transit train line. Since its release, the proposal has caused to copy and redistribute the material in any medium ongoing heated debate as it involves going underneath Singapore’s largest remaining reserve: or format and to remix, the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. Following extended discussions with environmental transform, and build upon the groups, the transport authority later stated that they would now consider two route options: a material for any purpose, even direct alignment running underneath the Central Reserve, and an alternative route that skirts commercially, provided the original work is properly cited the reserve boundary. The authority warned that the skirting option could increase the and states its license. construction cost significantly and cost commuters an extra few minutes of travel time. -

It's All Within Reach

SALES BROCHURE IT’s All WITHIN REACH MARINA BAY SANDS® Meetings. Incentives. Conferences. Exhibitions Contact us Sales Tel: +65 6688 3000 | Fax: +65 6688 3014 Email: [email protected] 10 Bayfront Avenue Singapore 018956 | MarinaBaySands.com/MICE Weddings and Dinner & Dances Tel: +65 6688 3133 Email: [email protected] 2015.06 ALL UNDER ONE ROOF ALL WITHIN REACH YOUR SINGAPORE Singapore is truly a city like no other. Located in the heart of fascinating Southeast Asia, this dynamic city rich in contrast and colour is where you’ll find a palette of cultures, cuisine, arts and architecture. Whether you’re here to take in the sights, indulge in culinary delights or seek out new adventures, there is something for everyone. Experience your Singapore the way you want. IT’s ALL WITHIN REACH View of pool from KU DÉ TA Marina Bay Sands® is Asia’s leading destination for business, leisure and entertainment. Home to Singapore’s largest meeting and convention space, it is our vision to redefine industry standards, delivering a world-class experience for you and your guests with unique venues unlike anywhere else, over 2,500 breathtaking rooms and suites, sumptuous dining, exciting entertainment and the finest in retail – all under one roof, all within reach. TOURIST ATTRACTIONS The following places can be reached within minutes 1 Jurong Bird Park (20 min) of driving from Marina Bay Sands. 2 Mandai Orchid Garden (30 min) To Malaysia 3 Singapore Zoological Gardens (30 min) Causeway 4 Night Safari (30 min) 5 Singapore Botanic Gardens -

ANNEX B Locations of the 120 Digital Traffic Red Light Cameras S/N Location 1 Adam Road by Sime Road Towards Lornie Road 2 Admi

ANNEX B Locations of the 120 Digital Traffic Red Light Cameras S/N Location 1 Adam Road by Sime Road towards Lornie Road 2 Admiralty Road by Marsiling Lane towards Woodlands Centre Road Admiralty Road by Woodlands Centre Road towards Bukit Timah 3 Expressway 4 Airport Road by Ubi Ave 2 towards Macpherson Road 5 Alexandra Road by Commonwealth Ave towards Tiong Bahru Road 6 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 10 towards Lor Chuan 7 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 8 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Central Expressway towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 10 9 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Central Expressway towards Lor Chuan 10 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Lor Chuan towards Boundary Road 11 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Marymount Rd towards Upper Thomson Road Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 by Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park 2 towards Central 12 Expressway 13 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 14 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 towards Lentor Ave 15 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 16 Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 Bedok North Ave 1 by Bedok North Street 1 towards New Upper 17 Changi Road 18 Bedok Reservoir Road by Bedok North Ave 3 towards Tampines Ave 4 Bedok South Ave 1 by Bedok South Road towards Upper East Coast 19 Road 20 Bishan Street 11 by Bishan Street 12 towards Bishan Street 21 21 Boon Lay Drive by Corporation Road towards Boon Lay Way 22 Boon Lay Way by Jurong East Central towards Jurong Town Hall Road 23 Brickland Road by Choa Chu Kang Ave 3 towards Bukit Batok Road Bukit Batok East -

Land Transport Masterplan

LAND TRANSPORT MASTERPLAN MP-endpaperproposal.indd 8-9 2/18/08 6:18:47 PM For Singapore to realise its aspirations to be a thriving global city, its transport infrastructure is critical. Over the next 10 to 15 years, the transport system must support economic growth, a bigger population, higher expectations and more diverse lifestyles. With this in mind, we embarked on a comprehensive Land Transport Review in October 2006. We solicited and benefited from contributions from a broad spectrum of people including students, workers, employers, commuters, transport operators, ordinary Singaporeans and experts; at home and abroad. In total, more than 4,500 people contributed their time, energies and ideas to this review. The culmination of this effort is a Land Transport Masterplan that strives to make Singapore a great city to live, work and play in. This calls for major MINISTER’S changes to vastly improve our land transport system. It is a plan to build and develop a more people-centred transport system that is technologically intelligent, yet engagingly human. FOREWORD Singaporeans can look forward to a more integrated and user-friendly public transport system. Fast and reliable bus services will complement a greatly expanded rail network to bring people where they want to go quickly. Tree-lined sheltered walkways in the heartlands and bustling underground walkways filled with shops in the city will ensure a pleasant walk to bus and train stations for all commuters. Varied transport choices like premium buses, taxis and cycling will help to cater to different needs. With the construction of new expressways, island-wide connectivity will also be significantly improved. -

SAL4847 MICE Sales Brochures Combined Trade and Leisure

Marina Bay Sands Layout/Artwork Approval Job Title Date Revision Spec Team SAL4847 04-01-2021 V11 Open Size : 440mmW x 305mmH Copywriter Carol Ad Manager CF MICE Sales Brochures e-book Close Size : 220mmW x 305mmH Combined Trade and Leisure_EN Color : 5C x 5C (pantone 872C) Material : 210gsm art card (cover), 157gsm matt art paper (inside) Designer Leon Stakeholder Finishing : Saddle stitch, (Cover and back cover- Matt lamination 2 sides, cover image spot UV ONE DESTINATION ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES Discover Asia’s leading destination for business and leisure TAKING YOU FROM BUSINESS TO LEISURE Strategically located in the heart of Southeast Asia, Singapore offers a vibrant cityscape which is well-connected, safe and technologically advanced. Its airport, Changi Airport, has been voted the World’s Best Airport for seven consecutive years*. *The Skytrax World Airport Awards, 2013–2019. THE FOLLOWING PLACES CAN BE REACHED WITHIN WHAT WE CAN OFFER YOU: MINUTES OF DRIVING FROM Over 2,500 rooms and suites Exclusive bespoke group MARINA BAY SANDS with stunning views experiences Over 80 dining options including Extensive and flexible To Malaysia award-winning restaurants meeting spaces Causeway Woodlands Over 270 world-class retail stores Multiple unique venues Checkpoint Singapore’s top must-see attractions Green meeting options 2 4 To Malaysia 3 24/7 world-class entertainment One-stop technical solution BKE Causeway Changi Airport (20 min) Tuas Checkpoint F Attractive rewards programmes A PIE AYE 1 5 6 7 ECP C 8 Tanah Merah 10 11 12 MCE Ferry Terminal -

GIS Data Hub Data Collection Specification - Part 2

RIMS Unit GIS Data Collection Specification GIS Data Hub Data Collection Specification - Part 2 16 Data Specification The details of the data to be submitted are as follows: 16.1 Arrow Marking (Point) Description: A point representation of an arrow painted on the road surface to advice motorists on the direction of traffic flow. Attribute Format: Field Name Data Size Precision Scale Allow Value Description Type Null TYP_CD String 4 0 0 No A, B, C, D, E, Please see Note 3 F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O BEARG_NUM Double 8 38 8 No Bearing. Please see Note 2 LVL_NUM Short 2 4 0 No Level of road where feature exists 2 At-grade (ground level) 8 1st level depressed road 9 1st level elevated road 7 2nd level depressed road 10 2nd level elevated road RD_CD Text 6 0 0 No Refer to list Road Code (assigned to the Road Name) where feature exists Notes: 1) Arrow Marking co-ordinate is the midpoint at the base of the arrow in the direction of the traffic flow. For example, a) Type C (straight / right turn shared arrow): one arrow only, hence only one point (x1, y1) required. b) Types G (left converging arrow) & H (right converging arrow): two arrows, hence two points (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are required. V2.5 Page 9 RIMS Unit GIS Data Collection Specification 2) The bearing should correspond with the bearing of each individual road. For example, if the bearing of the road is 97 degrees, then the bearing of arrow markings A is 97 degrees and the bearing of arrow markings B is 277 degrees respectively.