(2018) 35 Windsor Y B Access Just 304 George M. Duck Lecture Yasir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Legal Services Review

Ministry of the Attorney General Family Legal Services Review Report submitted to: Attorney General Yasir Naqvi and Treasurer Paul Schabas By: Justice Annemarie E. Bonkalo Date: December 31, 2016 December 31, 2016 The Honourable Yasir Naqvi Attorney General of Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General McMurtry-Scott Building 720 Bay Street, 11th Floor Toronto, ON M7A 2S9 Treasurer Paul Schabas The Law Society of Upper Canada Osgoode Hall 130 Queen Street West Toronto, ON M5H 2N6 Dear Attorney General Naqvi and Treasurer Schabas, Re: Family Legal Services Review On February 9, 2016, I was appointed by then Attorney General Madeleine Meilleur and then Treasurer of the Law Society of Upper Canada Janet Minor to lead a review of the provision of family legal services by persons other than lawyers. I have the honour to present to you my report in this matter. Yours sincerely, Justice Annemarie E. Bonkalo Disclaimer As set out in the Terms of Reference establishing the Family Legal Services Review, the Attorney General and the Treasurer of the Law Society of Upper Canada agreed to work together on a review of the provision of family legal services by persons in addition to lawyers. Chief Justice Lise Maisonneuve of the Ontario Court of Justice agreed to assign me to undertake this review. Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the following members of my advisory body for taking the time to meet with me and for their thoughtful consideration of the issues: • Lisa Bernstein • Nikki Gershbain • Judith Huddart • Hilary Linton • Alf Mamo • The Honourable Mary Jo Nolan • Elaine Page and • Noel Semple. -

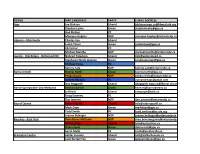

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen Leahy Green Rod Phillips PC Monique Hughes NDP Algoma—Manitoulin Charles Fox Liberal Justin Tilson Green Jib Turner PC Michael Mantha NDP Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian Liberal Stephanie Nicole Duncan Green Michael Parsa PC Katrina Sale NDP Barrie-Innisfil Bonnie North Green Pekka Reinio NDP Andrea Khanjin PC Ann Hoggarth Liberal Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Keenan Aylwin Green Jeff Kerk Liberal Doug Downey PC Dan Janssen NDP Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff Liberal Mark Daye Green Todd Smith PC Joanne Belanger NDP Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP Arthur Potts Liberal Debra Scott Green Sarah Mallo PC Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain Liberal Laila Zarrabi Yan Green Harjit Jaswal PC Sara Singh NDP Brampton East Dr. Parminder Singh Liberal Raquel Fronte Green Sudeep Verma PC Gurratan Singh NDP Brampton North Harinder Malhi Liberal Pauline Thornham Green Ripudaman Dhillon PC Kevin Yarde NDP Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi Liberal Lindsay Falt Green Prabmeet Sarkaria PC Paramjit Gill NDP Brampton West Vic Dhillon Liberal Julie Guillemet-Ackerman Green Amarjot Sandhu PC Jagroop Singh NDP Brantford - Brant Ruby Toor Liberal Ken Burns Green Will Bouma PC Alex Felsky NDP Bruce—Grey—Owen Sound Elizabeth Marshall Trillium Francesca Dobbyn Liberal Don Marshall Green Karen Gventer NDP Bill Walker PC Burlington Jane McKenna PC Eleanor McMahon Liberal Andrew Drummond NDP Vince Fiorito Green Cambridge Kathryn McGarry Liberal Michele Braniff Green Belinda Karahalios PC Marjorie -

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY E-MAIL ADDRESS Ajax Joe

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY E-MAIL ADDRESS Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal [email protected] Stephen Leahy Green [email protected] Rod Phillips PC Monique Hughes NDP [email protected] Algoma—Manitoulin Charles Fox Liberal Justin Tilson Green [email protected] Jib Turner PC Michael Mantha NDP [email protected] Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian Liberal [email protected] Stephanie Nicole Duncan Green [email protected] Michael Parsa PC Katrina Sale NDP [email protected] Barrie-Innisfil Bonnie North Green [email protected] Pekka Reinio NDP [email protected] Andrea Khanjin PC [email protected] Ann Hoggarth Liberal [email protected] Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Keenan Aylwin Green [email protected] Jeff Kerk Liberal [email protected] Doug Downey PC Dan Janssen NDP [email protected] Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff Liberal [email protected] Mark Daye Green [email protected] Todd Smith PC [email protected] Joanne Belanger NDP [email protected] Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP [email protected] Arthur Potts Liberal [email protected] Debra Scott Green [email protected] Sarah Mallo PC [email protected] Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain Liberal [email protected] Laila Zarrabi Yan Green [email protected] Harjit Jaswal PC [email protected] Sara Singh NDP [email protected] Brampton East Dr. Parminder Singh Liberal [email protected] Raquel Fronte Green [email protected] Sudeep Verma PC Gurratan -

Ontario Advocates' Response To

Ontario Advocates’ Response to BSL Assessment of the Breed Specific Components of Ontario’s Dog Owners Liability Act “I’m just a Dog” – A Look at the Reality of Breed Specific Legislation By Alix Packard Founder of Ottawa Citizens Against Breed Specific Legislation/BSL I would like to take a moment to thank my incredible partners who shared with me their own research, as well as with whom I consulted with in depth during the process of compiling this document: Fran Coughlin, Liz Sullivan and Cheryl Benson from Hershey’s Anti BSL Group, Debbie Black from Ontario “Pit Bull” Coop, Candy Beauchamp from Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club of Canada, Emily Clare from United Paws, and Hugh Patrick McGurnaghan from the PAC. Thank you all for your valued input, your friendship and your support. I would also like to thank Allie Brophy for sharing her educational program with me and allowing me to include it as our recommendation for children’s education for Ontario. Much love, Alix Table of Contents Chapter 1 – An Introduction; The History of Ontario’s BSL Chapter 2 – The Facts vs. The Myths Chapter 3 – The Resilience of “Pit Bull” Type Dogs Chapter 4 – The Courtney Trempe Inquest and the case of Christine Vadnais Chapter 5 – Fear Mongering and False Reporting Chapter 6 – The Effects of Panic Policy Making Chapter 7 – The Facts of Breed Specific Legislation Chapter 8 – The Cost of Enforcing Breed Specific Legislation in Ontario Chapter 9 – The Calgary Model Chapter 10 – The Conclusion Annex 1 – May 28, 2012 letter from Ontario Veterinary Medical Association Annex 2 - CANADA DOG BITE FATALITIES 1962 - Present Annex 3 – Ontario BSL vote results Feb 23, 2012 Annex 4 - School Curriculum Education Program: Safety and Awareness Around Your Dog and What To Do When You Meet a Dog You Don’t Know. -

October 26, 2015 the Honourable Kathleen Wynne Premier of Ontario

October 26, 2015 The Honourable Kathleen Wynne Premier of Ontario Legislative Building, Queens Park Toronto, ON M7A 1A1 [email protected] Dear Premier Wynne: RE: Northern Ontario Evacuations of First Nations Communities At its meeting held on October 21, 2015, the Board of Health for the Perth District Health Unit considered correspondence forwarded and supported by Peterborough County-City Health Unit (also referencing Sudbury District Board of Health, and the Thunder Bay District Board of Health) regarding evacuations of First Nations communities in Northern Ontario. The member municipalities of the Perth District Health Unit received evacuees from the James Bay area in 2008. The Board of Health remains deeply concerned that the First Nations communities of the James Bay Coast and Northwestern Ontario continue to require close to annual evacuation due to seasonal flooding and forest fires. The Board of Health for the Perth District Health Unit supports the recommendation to address the ongoing lack of resources and infrastructure to ensure the safe, efficient and effective temporary relocation of First Nations communities in Northwestern Ontario and the James Bay coast when they face environmental and weather related threats in the form of seasonal floods and forest fires. Thank you for your attention to this important matter. Sincerely, Teresa Barresi, Chair Board of Health, Perth District Health Unit TB/mr Cc: Hon. Eric Hoskins, Minister of Health and Long-Term Care Hon. Yasir Naqvi, Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services Hon. David Zimmer, Minister of Aboriginal Affairs Hon. Michael Gravelle, Minister of Northern Development and Mines Hon. Bill Mauro, Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry Linda Stewart, Executive Director, Association of Local Public Health Agencies MPP Randy Pettapiece Ontario Boards of Health . -

NEWS RELEASE for Immediate Release

Développement économique et Tourisme / Economic Development and Tourism Comtés unis de Prescott et Russell / United Counties of Prescott and Russell 59 rue Court St., C.P./P.O. Box 304 L’Orignal, ON K0B 1K0 NEWS RELEASE For immediate release Glengarry-Prescott-Russell Day impresses a sixth time Toronto, October 7, 2015 – It was with great pride that the United Counties of Prescott and Russell (UCPR) and the Township of North Glengarry held the sixth edition of Glengarry-Prescott-Russell Day this afternoon at Queen's Park. Since 2008, Glengarry-Prescott-Russell Day has allowed the region to showcase local food products in front of the entire Legislative Assembly of the Government of Ontario as well as members of their staff. Once again this year, more than 200 people took part in the event, including Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne, Ministers Jeff Leal, Madeleine Meilleur, Eric Hoskins and Yasir Naqvi, and Glengarry-Prescott-Russell MPP Grant Crack. “This day is important for our region because it affords us a rare opportunity to showcase our local food at the Provincial Parliament and, at the same time, advance and discuss our ongoing projects,” stated Robert Kirby, Warden of the United Counties of Prescott and Russell. The eight regional mayors representing the UCPR as well as Council members of the Township of North Glengarry were equally in attendance, and benefited from the opportunity to meet with several Ministers and their staff in order to advance economic development projects in the region. The showcased regional products include those of the St-Albert Cheese Cooperative, L’Orignal Packing, Skotidakis Goat Farm (St-Eugène), Mariposa Farm (Plantagenet), Cakes On St-Philippe (Alfred), Prima Cossa (L’Orignal), Vert Fourchette (Vankleek Hill), La Binerie Plantagenet, Beau’s All Natural Brewing Co. -

Do Good Intentions Beget Good Policy? Two Steps Forward and One Step Back in the Construction of Domestic Violence in Ontario

Do Good Intentions Beget Good Policy? Two Steps Forward and One Step Back in the Construction of Domestic Violence in Ontario by April Lucille Girard-Brown A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‟s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January, 2012 Copyright ©April Lucille Girard-Brown, 2012 Abstract The construction of domestic violence shifted and changed as this issue was forced from the private shadows to the public stage. This dissertation explores how government policy initiatives - Bill 117: An Act to Better Protect Victims of Domestic Violence and the Domestic Violence Action Plan (DVAP) - shaped our understanding of domestic violence as a social problem in the first decade of the twenty-first century in Ontario. Specifically, it asks whose voices were heard, whose were silenced, how domestic violence was conceptualized by various stakeholders. In order to do this I analyzed the texts of Bill 117, its debates, the DVAP, as well as fourteen in-depth interviews with anti- violence advocates in Ontario to shed light on their construction of the domestic violence problem. Then I examined who (both state and non-state actors) regarded the work as „successful‟, flawed or wholly ineffective. In particular, I focused on the claims and counter-claims advanced by MPPs, other government officials, feminist or other women‟s group advocates and men‟s or fathers‟ rights group supporters and organizations. The key themes derived from the textual analysis of documents and the interviews encapsulate the key issues which formed the dominant construction of domestic violence in Ontario between 2000 and 2009: the never-ending struggles over funding, debates surrounding issues of rights and responsibilities, solutions proposed to address domestic violence, and finally the continued appearance of deserving and undeserving victims in public policy. -

(2018) 35 Windsor Y B Access Just 304 George M. Duck Lecture Yasir

George M. Duck Lecture Yasir Naqvi* The Hon. Yasir Naqvi, Attorney General of Ontario, delivered the George M. Duck Lecture at the University of Windsor Faculty of Law on February 28, 2018. I would like to acknowledge that we are meeting today on the traditional lands of the Three Fires Confederacy, which is comprised of the Ojibway, the Odawa, and the Potawatomi. It is important that we recognize the long history of First Nations and Métis Peoples in Ontario and that we continue to show them respect today. It is wonderful to be here at the University of Windsor Law School as you celebrate your 50th year. Thank you to the University for allowing me the distinct honour of presenting this year’s George M. Duck lecture, a tradition that almost extends to the birth of the law school itself. I. GEORGE M. DUCK LECTURE SERIES So many significant figures of our Canadian legal and political landscape have stood within these very walls to deliver this lecture. Jean Chrétien and John Turner, when each was the federal Minister of Justice, Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Abella and Roberta Jamieson, the first Indigenous woman to earn a law degree in Canada, and Ontario’s Ombudsman at the time. I am honoured and humbled to join this distinguished group. II. LESSONS FROM MY YOUTH As a law student 20 years ago, I would never have thought my career would lead me here and certainly not as a kid growing up in Karachi. When I was growing up in Karachi, my parents – who were both lawyers – were involved in the pro- democracy movement. -

Ontario This Month

Innovative Research Group, Inc. www.innovativeresearch.ca Toronto :: Vancouver Public Opinion Research Ontario This Month Provincial Liberal Leadership Field Dates: October 17 – 22, 2012 Sample Size: n=600; MoE ±4.0% October 2012 © 2012 Copyright Innovative Research Group Inc. 2 Key Takeaways Leadership race and OLP renewal . The leadership race moves many non-Liberals onto the fence; many indicated with the right leader, they are willing to give the party a second look. Four-in-ten Ontarians only looking for minor changes from government. Ontarians are looking for a new Liberal leader who will reduce unemployment and create new jobs, have a more honest and accountable governance style and focus on social policies. Potential candidates . Even best-known candidates not well-known among general public. Among those tested, Dwight Duncan does best among core Liberals, and Kathleen Wynne does best among potential Liberals. McGuinty’s legacy . McGuinty legacy depends on current political preference. 3 Methodology • Telephone survey of approximately 600 adults, 18 years and older conducted (Prior to April 2003 approximately 650 adults): – 2000 – April 14-25; May 15-27; June 21-29; July 15-23; Aug 16-21; Sept 22-Oct 3; Oct 27-Nov 1; Nov 24-28; Dec14-18. – 2001 – Jan 15-17; Feb 27-March 2; March 22-26; April 26-30; May 25-30; June 22-28; July 19-26; Aug 23-30; Sept 20-27; Oct 18- 25, Nov 23-29, Dec 13-20. – 2002 – Jan 15-21; Feb 22-28; March 12-17; April 10-14; May 16-21; June 21-26; July 18-23; Aug 20-26; Sept 16-23; Oct 18-23; Nov 18-22; Dec 11-14. -

Re the Honourable Bob Chiarelli the Honourable Michael Coteau and the Honourable Yasir Naqvi, December 8

Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l’Ontario OFFICE OF THE INTEGRITY COMMISSIONER ~ REPORT OF THE HONOURABLE J. DAVID WAKE INTEGRITY COMMISSIONER RE: THE HONOURABLE BOB CHIARELLI, THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL COTEAU AND THE HONOURABLE YASIR NAQVI TORONTO, ONTARIO December 8, 2016 RE: THE HONOURABLE BOB CHIARELLI, THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL COTEAU AND THE HONOURABLE YASIR NAQVI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report relates to a request made by Catherine Fife, the Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) for Kitchener-Waterloo, under section 30 of the Members’ Integrity Act, 1994 (the “ Act ”) about (1) Bob Chiarelli , MPP for Ottawa West-Nepean and Minister of Infrastructure, (2) Michael Coteau , MPP for Don Valley East and Minister of Child and Youth Services and (3) Yasir Naqvi , MPP for Ottawa Centre and Government House Leader and Attorney General (the “Ministers ”). Ms. Fife alleged that in contravention of section 2 of the Act the Ministers instructed staff in their respective ministerial offices to participate in partisan fundraising activities such that the Ministers furthered their own private interests by: (a) helping them to achieve the fundraising quotas assigned to them by the Ontario Liberal Party (the “ OLP ”) with the consent of the Premier, and (b) benefiting as future candidates from contributions to the OLP. Ms. Fife also alleged that by instructing their staff to engage in these activities, the Ministers blurred the lines between partisan fundraising and government business. In my opinion, the Ministers did not contravene section 2 of the Act because their private interests were not engaged. I found no evidence that fundraising quotas were assigned to the Ministers and that any benefit to them as future candidates would be too remote to be considered a private interest. -

2018 Ontario Candidates List May 8.Xlsx

Riding Ajax Joe Dickson ‐ @MPPJoeDickson Rod Phillips ‐ @RodPhillips01 Algoma ‐ Manitoulin Jib Turner ‐ @JibTurnerPC Michael Mantha ‐ @ M_Mantha Aurora ‐ Oak Ridges ‐ Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian ‐ @yaqubian Michael Parsa ‐ @MichaelParsa Barrie‐Innisfil Ann Hoggarth ‐ @AnnHoggarthMPP Andrea Khanjin ‐ @Andrea_Khanjin Pekka Reinio ‐ @BI_NDP Barrie ‐ Springwater ‐ Oro‐Medonte Jeff Kerk ‐ @jeffkerk Doug Downey ‐ @douglasdowney Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff ‐ @RQuaiff Todd Smith ‐ @ToddSmithPC Joanne Belanger ‐ No social media. Beaches ‐ East York Arthur Potts ‐ @apottsBEY Sarah Mallo ‐ @sarah_mallo Rima Berns‐McGown ‐ @beyrima Brampton Centre Harjit Jaswal ‐ @harjitjaswal Sara Singh ‐ @SaraSinghNDP Brampton East Parminder Singh ‐ @parmindersingh Simmer Sandhu ‐ @simmer_sandhu Gurratan Singh ‐ @GurratanSingh Brampton North Harinder Malhi ‐ @Harindermalhi Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi ‐ @SukhwantThethi Prabmeet Sarkaria ‐ @PrabSarkaria Brampton West Vic Dhillon ‐ @VoteVicDhillon Amarjot Singh Sandhu ‐ @sandhuamarjot1 Brantford ‐ Brant Ruby Toor ‐ @RubyToor Will Bouma ‐ @WillBoumaBrant Alex Felsky ‐ @alexfelsky Bruce ‐ Grey ‐ Owen Sound Francesca Dobbyn ‐ @Francesca__ah_ Bill Walker ‐ @billwalkermpp Karen Gventer ‐ @KarenGventerNDP Burlington Eleanor McMahon ‐@EMcMahonBurl Jane McKenna ‐ @janemckennapc Cambridge Kathryn McGarry ‐ Kathryn_McGarry Belinda Karahalios ‐ @MrsBelindaK Marjorie Knight ‐ @KnightmjaKnight Carleton Theresa Qadri ‐ @TheresaQadri Goldie Ghamari ‐ @gghamari Chatham‐Kent ‐ Leamington Rick Nicholls ‐ @RickNichollsCKL Jordan -

Inside Queen's Park

INSIDE QUEEN’S PARK Vol. 26, No. 22 GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL ANALYSIS November 7, 2013 AT THE CUTTING EDGE: ‘CREATURES OF THE Prevention Act which will stop use of tanning beds by PROVINCE’ DOESN’T BEGIN TO DO JUSTICE TO young people. Among MPPs attending were Health THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE PROVINCE minister Deb Matthews and both opposition critics, PC OF ONTARIO AND THE CITY OF TORONTO. Christine Elliott and NDPer France Gélinas, the In Ontario, municipalities purportedly operate original advocate of the tanning ban. (The next within strict limitations imposed by Queen’s Park. The campaign by the Cancer Society is to ban all types of local electoral framework, like all other significant flavoured tobacco, another cancer reform first elements of governance, is controlled by provincial advocated by Gélinas.) legislation, making municipalities ‘creatures of the The event was IQP ‘s first exposure to a healthy province’. This severely constrains the scope for breakfast component termed ‘turkey-bacon’ (or its provincial intervention in respect to what might be second cousin, ‘chicken-bacon’) which presents as flat called ordinary circumstances. Yet, paradoxically, the and rather dry identically sized strips. The good comprehensive prohibitions against interfering in people at Eurest Food Services are surely right to humdrum local government activities themselves consider that to be a healthier element of a cooked constitutes a strong argument that the provincial breakfast than mounds of what might be called pre- government is obliged to address an alarming crisis in manufactured bacon. Visual appeal is a less compelling the democratic governance of the principal Ontario consideration.