With Works from the Collection of Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOOK Exhibition Checklist (PDF .37MB)

LOOK: Charles Darwin University Art Collection Charles Darwin University Art Gallery 29 February – 29 June 2012 Chancellery Building Orange 12.1.02 Casuarina Campus 1 Sidney Wilson 100 x 50cm [image]; 120 x 73.5 cm [paper] Dugong 2008 Gifted by the artist & Northern Editions Synthetic polymer paint on canoe tree Printmaking Studio, 2010 – CDU1890 wood; black glass beads 50cm [length] x 9cm [width], approx. 7 Bronwyn Wright Acquired by purchase, 2011 – CDU2294 Leaping Dog 2005 Digital type C print (colour on metallic paper) 2 Therese Ritchie 26.8 x 36.1 cm [image]; 30 x 39cm [paper] Luju ka wirntimi (Woman Dancing) [2000] Gifted by the artist, October 2006 – CDU1287 Inkjet print on German etching paper 59.5 x 60cm [image] 8 Susan Marawarr NDY Edition, 2010 – on loan from the artist Korlngkarri (place name) 1999 Screenprint, WP edn 25 3 Therese Ritchie Collaborators: Leon Stainer/Monique Auricchio Wati-jarra kapala jurrka-pinyi (Two men Printer: Gilbert Herrada dancing) [2000] 49 x 68.5cm [image]; 56 x 76cm [paper] Inkjet print on German etching paper Gifted by the artist & Northern Editions 59.5 x 60cm [image] Printmaking Workshop, 1999 – NTU730 NDY Edition, 2010 – on loan from the artist 9 Angelina George 4 Therese Ritchie Rainbow Serpent Dreaming 2004 Luju ka wirntimi (Woman Dancing) 2 [2000] Acrylic on linen, 121 x 96 cm Inkjet print on German etching paper Acquired by purchase, December 2005 – 59.5 x 60cm [image] CDU1272 NDY Edition, 2010 – on loan from the artist 10 Pepai Jangala Carroll 5 Kuruwarriyingathi Bijarrb (Paula Paul) Ininti -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

MAKINTI NAPANANGKA – PINTUPI C

MAKINTI NAPANANGKA – PINTUPI c. 1930 - 2011 Represented by Utopia Art Sydney, 2 Danks Street, Waterloo, NSW 2017 © Makinti Napanangka was born at Lupul rockhole south of Kintore c. 1930. She gave birth to her first child in the Lake MacDonald area and later had children in Haasts Bluff, Papunya and Alice Springs. She walked with her family to Haasts Bluff before the Papunya Community was established. Makinti began painting regularly for the company in 1996. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2007 "Makinti" Papunya Tula Artists, Alice Springs 2005 "Makinti" John Gordon Gallery, Coffs Harbour 2003 “Makinti Napanangka – A Painter” Utopia Art Sydney 2002 “Recent Paintings” Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi 2001 “Makinti Napanangka: new paintings”” Utopia Art Sydney 2000 “Makinti Napanangka: New Vision” Utopia Art Sydney SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2013 ‘The Salon’, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW ‘No Boundaries’, Bayside Arts & Cultural Centre, VIC 2012 ‘Abstraction’, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW ‘Kunga: Les Femmes de Loi du Desert (Law Women From the Desert)’, the collection of Arnaud et Berengere Serval, Galerie Carry On / Art Aborigene, Geneva ‘Ancestral Modern: Australian Aboriginal Art from the Kaplan & Levi Collection’, Seattle Art Museum, USA ‘18th Biennale of Sydney: all our relations’, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, NSW ‘Interconnected’, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW ‘Unique Perspectives: Papunya Tula Artists and the Alice Springs Community,’ Araluen Arts Centre, NT 2011 ‘Papunya Tula Women’s Art’, Maitland Regional Art Gallery, NSW ’40 Years of Papunya Tula Artists’, Utopia -

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2Pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Tional in Fi Le Only - Over Art Fi Le

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia tional in fi le only - over art fi le 5 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 6 7 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 1 2 Bonhams Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Bonhams Viewing Specialist Enquiries Viewing & Sale 76 Paddington Street London Mark Fraser, Chairman Day Enquiries Paddington NSW 2021 Bonhams +61 (0) 430 098 802 mob +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 101 New Bond Street [email protected] +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax Thursday 14 February 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] Friday 15 February 9am to 4.30pm Greer Adams, Specialist in Press Enquiries www.bonhams.com/sydney Monday 18 February 9am to 4.30pm Charge, Aboriginal Art Gabriella Coslovich Tuesday 19 February 9am to 4.30pm +61 (0) 414 873 597 mob +61 (0) 425 838 283 Sale Number 21162 [email protected] New York Online bidding will be available Catalogue cost $45 Bonhams Francesca Cavazzini, Specialist for the auction. For futher 580 Madison Avenue in Charge, Aboriginal Art information please visit: Postage Saturday 2 March 12pm to 5pm +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob www.bonhams.com Australia: $16 Sunday 3 March 12pm to 5pm [email protected] New Zealand: $43 Monday 4 March 10am to 5pm All bidders should make Asia/Middle East/USA: $53 Tuesday 5 March 10am to 5pm Tim Klingender, themselves aware of the Rest of World: $78 Wednesday 6 March 10am to 5pm Senior Consultant important information on the +61 (0) 413 202 434 mob following pages relating Illustrations Melbourne [email protected] to bidding, payment, collection fortyfive downstairs Front cover: Lot 21 (detail) and storage of any purchases. -

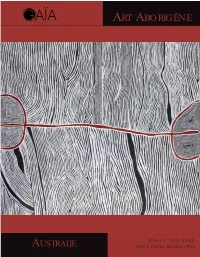

Art Aborigène

ART ABORIGÈNE LUNDI 1ER JUIN 2009 AUSTRALIE Vente à l’Atelier Richelieu - Paris ART ABORIGÈNE Atelier Richelieu - 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Vente le lundi 1er juin 2009 à 14h00 Commissaire-Priseur : Nathalie Mangeot GAÏA S.A.S. Maison de ventes aux enchères publiques 43, rue de Trévise - 75009 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 00 - Fax : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 01 E-mail : [email protected] - www.gaiaauction.com Exposition publique à l’Atelier Richelieu le samedi 30 mai de 14 h à 19 h le dimanche 31 mai de 10 h à 19 h et le lundi 1er juin de 10 h à 12 h 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Maison de ventes aux enchères Tous les lots sont visibles sur le site www.gaiaauction.com Expert : Marc Yvonnou 06 50 99 30 31 I GAÏAI 1er juin 2009 - 14hI 1 INDEX ABRÉVIATIONS utilisées pour les principaux musées australiens, océaniens, européens et américains : ANONYME 1, 2, 3 - AA&CC : Araluen Art & Cultural Centre (Alice Springs) BRITTEN, JACK 40 - AAM : Aboriginal Art Museum, (Utrecht, Pays Bas) CANN, CHURCHILL 39 - ACG : Auckland City art Gallery (Nouvelle Zélande) JAWALYI, HENRY WAMBINI 37, 41, 42 - AIATSIS : Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres JOOLAMA, PADDY CARLTON 46 Strait Islander Studies (Canberra) JOONGOORRA, HECTOR JANDANY 38 - AGNSW : Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) JOONGOORRA, BILLY THOMAS 67 - AGSA : Art Gallery of South Australia (Canberra) KAREDADA, LILY 43 - AGWA : Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth) KEMARRE, ABIE LOY 15 - BM : British Museum (Londres) LYNCH, J. 4 - CCG : Campbelltown City art Gallery, (Adelaïde) -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

Every 23 Days

CONTENTS 11 Foreword 13 Introduction 15 Essay: Every 23 days... 17-21 Asialink Visual Arts Touring Exhibitions 1990-2010 23-86 Venue List 89-91 Index 92-93 Acknowledgements 94 FOREWORD 13 Asialink celebrates twenty years as a leader in Australia-Asia engagement through business, government, philanthropic and cultural partnerships. Part of the celebration is the publication of this booklet to commemorate the Touring Visual Arts Exhibitions Program which has been a central focus of Asialink’s work over this whole period. Artistic practice encourages dialogue between different cultures, with visual arts particularly able to transcend language barriers and create immediate and exciting rapport. Asialink has presented some of the best art of our time to large audiences in eighteen countries across Asia through exhibition and special projects, celebrating the strength and creativity on offer in Australia and throughout the region. The Australian Government, through the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, is pleased to provide support to Asialink as it continues to present the talents of artists of today to an ever increasing international audience. The Hon Stephen Smith MP Minister for Foreign Affairs INTRODUCTION 15 Every 23 Days: 20 Years Touring Asia documents the journey of nearly 80 Australian-based contemporary exhibitions’ history that have toured primarily through Asia as a part of the Asialink Touring Exhibition Program. This publication provides a chronological and in-depth overview of these exhibitions including special country focused projects and an introductory essay reflecting on the Program’s history. Since its inception in 1990, Asialink has toured contemporary architecture, ceramics, glass, installation, jewellery, painting, photography, textiles, video, works on paper to over 200 venues in Asia. -

Fireworks Gallery Exhibitions | 1993 - 2021

FireWorks Gallery Exhibitions | 1993 - 2021 1993 | George Street, Brisbane Political Works Campfire Group - Featuring Richard Bell, Michael Eather & Marshall Bell 6 May Firebrand Group Exhibition Rebels without a Course David Paulson & his Rebel Art Students 22 Aug - 8 Sept Political Bedrooms Group Exhibition - Installation works 22 Sept - 15 Oct 1994 | George Street, Brisbane Political Boats Group Exhibition - Installation work & mixed media 18 Mar - 9 Apr Cultural Debris Laurie Graham & David Darby Apr Utopia Artists - Featuring Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Sue Elliot & Christopher Dialogue 29 Apr - 17 May Hodges Tiddas Buddas - Works on Paper North Queensland Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Artists Jun Indigenous Sculpture and Mixed media North Queensland Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Artists Jul Lajamanu - Desert Paintings Group Exhibition Photographs Robert Mercer 22 Jul - 6 Aug Paintings Ruby Abbott Napangardi South West Queensland Stories Featuring Robert White & Joanne Currie Nalingu Aug That's women all over Group Exhibition - Curated by Joyce Watson Sept Prints and Weavings from the Torres Group Exhibition Sept Strait Islands 24 Hours by the Billabong Lin Onus Oct Paintings & Sculptures Laurie Nilsen Paintings Rod Moss Nov Indigenous Prisoners Exhibition Group Exhibition Dec Group Exhibition (touring) - Featuring Ian Burn, Albert Namatjira, Kim A Different View 9 Dec - 1 Jan 1995 Mahood & Joanne Currie Nalingu 1995 | Ann Street, Fortitude Valley Timeless Land Vincent Serico Jun Dwelling in Arrente Country Rod Moss Jul Group -

Art Contemporain Aborigène D'australie

Art Contemporain Aborigène d’Australie 1 21 mai 2015 6, avenue Hoche ART IMPRESSIONNISTEARTART ET ABORIGENE MODERNE CornetteCornette dede SaintSaint CyrCyr 212730 maioctobremars 2015 2015 2014 2 ARTSUCCESSION IMPRESSIONNISTE HANS RICHTER ET MODERNE Hôtel SalomonCornette de de Rothschild Saint Cyr 9 avril 201430 mars 2015 Art Contemporain Aborigène d’Australie Collection Arnaud Serval Jeudi 21 mai 2015 à 19h30 Expositions publiques : Directeur du département : Mardi 19 mai 14h-18h Stéphane Corréard Mercredi 20 mai 11h-19h30 Tél. + 33 1 56 79 12 31 – Fax + 33 1 45 53 45 24 Jeudi 21 mai 11h-19h30 [email protected] 1 Téléphone pendant la vente Spécialiste : +33 1 56 79 12 60 Sabine Cornette de Saint Cyr Tél. + 33 1 56 79 12 32 – Fax + 33 1 45 53 45 24 Cornette de Saint Cyr [email protected] 6, avenue Hoche – Paris 8 eme +33 1 47 27 11 24 Administratrice de vente : Clara Golbin Tél. + 33 1 47 27 11 24 – Fax + 33 1 45 53 45 24 [email protected] Contact : Hélène Martin Tél. +33 1 56 79 12 39 – Fax + 33 1 45 53 45 24 [email protected] Les rapports de conditions des œuvres que nous présentons peuvent être délivrés avant la vente à toutes les personnes qui en font la demande. Ceux-ci sont uniquement procurés à titre indicatif et ne peuvent en aucun cas se substituer à l’examen personnel de celles-ci par l’acquéreur. Commissaire-priseur : Arnaud Cornette de Saint Cyr Tél. +33 1 47 27 11 24 [email protected] Toutes les oeuvres de la collection Arnaud Serval sont en importation temporaire et sont soumises à une TVA de 5,5% sur le prix d’adjudication. -

Jahrbuch Der Staatlichen Ethnographischen Sammlungen Sachsen

ISSN 1865-4347 Sonderdruck aus Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Ethnographischen Sammlungen Sachsen BAND XLVI 2013 JAHRBUCH DER STAATLICHEN ETHNOGRAPHISCHEN SAMMLUNGEN SACHSEN Band XLVI Herausgegeben vom Direktor Claus Deimel VWB – Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung • Berlin 2013 Redaktion: Giselher Blesse, Lydia Hauth Die Autoren sind für den Inhalt ihrer Abhandlungen selbst verantwortlich. Die Rechtschreibung folgt den Intentionen der Autoren. Fotos bzw. Umzeichnungen: Archiv Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig/SES; Beatrice von Bismarck; Thomas Dachs; Alexis Daflos; Claus Deimel; Amanda Dent|Tjungu Palya; Silvia Dolz; Mark Elliot; Frank Engel; Amina Grunewald; Corrine Hunt; E. L. Jensen; Rolf killius; H.-P. klut/E. Estel (SkD); Carola krebs; Sylvia krings|ARTkELCH; Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde Leipzig (Bildarchiv); katja Müller; Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden/SES, Bildarchiv; Photographic Archives, Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville, kentucky; The Trustees of the British Museum, London, Archiv; Tony Sandin; Birgit Scheps; Erhard Schwerin; Spinifex Arts Projects; Stadtarchiv Leipzig; Tjala Arts; Unitätsarchiv der Evangelischen Brüder-Unität Herrnhut; Frank Usbeck; Warlukurlangu Artists; Frederick Weygold; Eva Winkler; Völkerkundemuseum Herrnhut/SES Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-86135-792-6 ISSN 1865-4347 © Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen/Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden 2013. Erschienen im: VWB – Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, Amand Aglaster • Postfach 11 03 68 • 10833 Berlin Tel. 030-251 04 15 • Fax: 030-251 11 36 www.vwb-verlag.com • [email protected] Printed in Germany Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Ethnographischen Sammlungen Sachsen Band XLVI Inhalt Vorwort: Entwicklungen in den Jahren 2010, 2011 und 2012 . -

Digital Works Over the Last Five Months As Part of Her

digital works over the last five months as part of her Masters Degree, Judith hopes her exhibition Delve Deep in Second Life will encourage people to push past their current existence and open their minds to the new world of digital art and 3D spaces. www.theprogram.net.au Papunya Tula art show a near sell-out Over 200 Buyers from across the country flew into Alice Springs for the Aboriginal-owned gallery’s November Exhibition, spending a total of $450 000 over two days. Makinti Napanangka’s 19 works on offer were all sold, with George Tjungurrayi’s work, Tingarri Men Travelling to the site of Mamultjulkulnga, fetching the highest individual price of $80 000. Papunya Tula assistant manager Luke Scholes said profits will go to the artists and their communities. www.dcm.nt.gov.au Warlpiri Media nominated for the 2007 Human Rights Award Yuendumu-based Warlpiri Media Association, which interviews the locals, has been nominated for the 2007 Human Rights Award in the print media category -- in partnership with Reconciliation Australia and News Limited, publisher of The Australian -- by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. www.theaustralian.news.com.au Free speech being whittled away Free speech in Australia is being whittled away by legal restrictions and a secretive culture among public officials, according to a new report on press freedom. Author of the report, former NSW ombudsman Irene Moss, says there are grounds for concern about the state of free speech in Australia. Her audit, commissioned by a coalition of major media groups, says there are 500 pieces of legislation and at least 1,000 court suppression orders still in force that restrict media reporting in Australia. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2018-19

Annual Report 2018–19 The Art Gallery of New South Wales ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 2 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 The Gadigal people of the Eora nation are the traditional custodians of the land on which the Art Gallery of New South Wales is located. The Hon Don Harwin MLC Minister for the Arts Parliament of New South Wales Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister, It is our pleasure to forward to you for presentation to the NSW Parliament the Annual Report for the Art Gallery of New South Wales for the year ended 30 June 2019. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Report (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulations 2010. Yours sincerely, Mr David Gonski AC Dr Michael Brand President Director Art Gallery of New South Wales Trust Art Gallery of New South Wales 12 October 2019 Contents 8 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD 10 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 14 STRATEGIC GOAL 1: CAMPUS 16 STRATEGIC GOAL 2: ART 50 STRATEGIC GOAL 3: AUDIENCE 58 STRATEGIC GOAL 4: STRENGTH 68 STRATEGIC GOAL 5: PEOPLE 91 FINANCIAL REPORTS © Art Gallery of New South Wales Compiled by Emily Crocker Designed by Trudi Fletcher Edited by Lisa Girault Art Gallery of New South Wales ABN 24 934 492 575. Entity name: The Trustee for Art Gallery of NSW Trust. The Art Gallery of New South Wales is a statutory body established under the Art COVER: Grace Cossington Smith, The window 1956, Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980 and, oil on hardboard, 121.9 x 91.5 cm, Art Gallery of from 15 March 2017 to 30 June 2019, an New South Wales, gift of Graham and Judy Martin 2014, executive agency related to the Department assisted by the Australian Masterpiece Fund © Estate of of Planning and Environment.