V Seepersad and Another (Appellants) (Trinidad and Tobago)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday October 12, 2015

319 Standing Finance Committee Monday, October 12, 2015 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Monday, October 12, 2015 The House met at 10.00 a.m. PRAYERS [MADAM SPEAKER in the Chair] STANDING FINANCE COMMITTEE Madam Speaker: Hon. Members, the order for the consideration of the Heads of Expenditure in the Standing Finance Committee was submitted by the Leader of the Opposition on Friday, October 09, 2015 in accordance with Standing Order 84(2). This should by now have been circulated to all hon. Members via email. As provided for in Standing Order 83(1), five days are allotted for Standing Finance Committee to examine the estimates of expenditure together with the Appropriation Bill. The proceedings of the committee will formally commence on Thursday, October 15, 2015. However, time permitting, I suggest that the Motion to resolve into Standing Finance Committee be moved on Wednesday, October 14, 2015 only to permit Standing Finance Committee to finalize the agenda and hold preliminary discussions on the procedures to be followed. I do hope that Members will find this arrangement to be in order. APPROPRIATION (FINANCIAL YEAR 2016) BILL, 2015 [Fourth Day] Order read for resuming adjourned debate on question [October 09, 2015]: That the Bill be now read a second time. Question again proposed. Madam Speaker: I now call on the Member for San Fernando West. The Attorney General (Hon. Faris Al-Rawi): [Desk thumping] Much obliged. Madam Speaker, it is a sincere privilege and an honour to be an elected Member of the House of Representatives of Trinidad and Tobago. I am extremely grateful to God the Almighty for having taken us through the journey that brought us here. -

Trinidad and Tobago | Freedom House Page 1 of 15

Trinidad and Tobago | Freedom House Page 1 of 15 TrinidadFREEDOM IN and THE WORLDTobago 2020 82 FREE /100 Political Rights 33 Civil Liberties 49 82 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. TOP Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/trinidad-and-tobago/freedom-world/2020 7/24/2020 Trinidad and Tobago | Freedom House Page 2 of 15 The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is a parliamentary democracy with vibrant media and civil society sectors. However, organized crime contributes to high levels of violence, and corruption among public officials remains a challenge. Other security concerns center on local adherents of Islamist militant groups. There is discrimination against the LGBT+ community, though a 2018 court ruling effectively decriminalized same-sex sexual conduct. Key Developments in 2019 • The government offered work permits to Venezuelan refugees and asylum seekers during a two-week period in June. Those who did not successfully register remained vulnerable to detention and deportation, and some applicants did not receive registration cards until December. • Several current and former government ministers and officials were accused of corruption during the year; former attorney general Anand Ramlogan was arrested for money laundering in May, while public administration minister Marlene McDonald was arrested and charged in August. Cases against both individuals were pending at year’s end. • Watson Duke, leader of the Progressive Democratic Patriots (PDP) party, was charged with sedition -

Faculty Report 2013/2014

FACULTY REPORT 2013/2014 FACULTY OF ENGINEERING 02 FACULTY OF FOOD & AGRICULTURE 16 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES & EDUCATION 26 FACULTY OF LAW 44 FACULTY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES 50 FACULTY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 62 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES 78 CENTRES & INSTITUTES 90 PUBLICATIONS AND CONFERENCES 134 1 Faculty of Engineering Professor Brian Copeland Dean, Faculty of Engineering Executive Summary For the period 2013-2014, the Faculty of Engineering continued its major activities in areas such as Curriculum and Pedagogical Reform (CPR) at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, Research and Innovation, and providing Support Systems (Administrative and Infrastructure) in keeping with the 2012-2017 Strategic Plan. FACULTY OF ENGINEERING TEACHING & LEARNING Accreditation Status New GPA During the year under review, the BSc Petroleum The year under review was almost completely Geoscience and MSc Petroleum Engineering dedicated to planning for the transition to a new GPA programmes were accredited by the Energy Institute, system scheduled for implementation in September UK. In addition, the relatively new Engineering Asset 2014. The Faculty adopted an approach where the new Management programme was accredited for the GPA system was applied to new students (enrolled period 2008 to 2015, thus maintaining alignment September 2014) only. Continuing students remain with other iMechE accredited programmes in the under the GPA system they encountered at first Department. registration. The Faculty plans to implement the new GPA scheme on a phased basis over the next academic The accreditation status of all BSc programmes and year so that by 2016–2017, all students will be under the those MSc programmes for which accreditation was new scheme. -

Final Report on the IPI Advocacy Mission to End Criminal Defamation in the Caribbean

Final Report on the IPI Advocacy Mission to End Criminal Defamation in the Caribbean Barbados, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago 9 – 21 June 2012 In cooperation with: The Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers (ACM) 1. Introduction Background In June 2012, the International Press Institute (IPI), in conjunction with its strategic partner, the Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers (ACM), conducted a two-week mission to Barbados, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic and Trinidad and Tobago as part of its wider campaign to end criminal defamation in the Caribbean. The ultimate aim of the campaign is to push for the abolition of criminal laws currently in place in the Caribbean that concern defamation, slander, libel or insult. The campaign encourages the use of civil laws to address such concerns, in line with international press-freedom standards and the recommendations expressed by regional and international human-rights bodies. Currently, all 13 independent states in the Caribbean have criminal defamation laws on their books that establish a penalty of at least one year in prison. Libel deemed seditious or obscene remains a separate offence in a majority of Caribbean countries and generally entails stiffer punishments, with prison sentences of up to five years in certain cases. Particularly in the English-speaking Caribbean, many of the laws in place are near-exact replicas of colonial-era acts dating back to the mid-19th century. Lord Campbell’s Act (also known as the Libel Act of 1843), which serves as the foundation for a number of defamation statutes across the Caribbean, was itself largely repealed in England in 2009. -

20140610, Senate Debate

185 SENATE Tuesday, June 10, 2014 The Senate met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. PRESIDENT in the Chair] LEAVE OF ABSENCE Mr. President: Hon. Senators, I have granted leave of absence to Sen. Avinash Singh, who is out of the country and Sen. H. R. Ian Roach who is ill. SENATORS’ APPOINTMENT Mr. President: Hon. Senators, I have received the following correspondence from His Excellency the President, Anthony Thomas Aquinas Carmona, O.R.T.T. S.C.: “THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By His Excellency ANTHONY THOMAS AQUINAS CARMONA, O.R.T.T., S.C., President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. /s/ Anthony Thomas Aquinas Carmona O.R.T.T. S.C. President TO: DR. AYSHA B. EDWARDS WHEREAS Senator Hugh Russell Ian Roach is incapable of performing his duties as a Senator by reason of his illness: NOW, THEREFORE, I, ANTHONY THOMAS AQUINAS CARMONA, President as aforesaid, in exercise of the power vested in me by section 44(1)(b) and section 44(4)(c) of the Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, do hereby appoint you, AYSHA B. EDWARDS, to be temporarily a member of the Senate, with effect from 10th June, 2014 and continuing during the absence from Trinidad and Tobago of the said Senator Hugh Russell Ian Roach. Given under my Hand and the Seal of the President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago at the Office of the President, St. Ann’s, this 10th day of June, 2014.” “THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 186 By His Excellency ANTHONY THOMAS AQUINAS CARMONA, O.R.T.T., S.C., President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. -

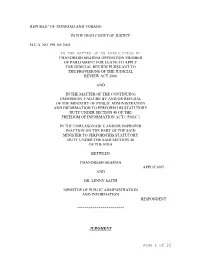

Chandresh Sharma V Lenny Saith

REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE H.C.A. NO. 991 OF 2005 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY CHANDRESH SHARMA OPPOSITION MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR LEAVE TO APPLY FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW PURSUANT TO THE PROVISIONS OF THE JUDICIAL REVIEW ACT 2000 AND IN THE MATTER OF THE CONTINUING OMMISSION, FAILURE BY AND/OR REFUSAL OF THE MINISTRY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND INFORMATION TO PERFORM HIS STATUTORY DUTY UNDER SECTION 40 OF THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT (“FOIA”) IN THE UNREASONABLE AND/OR IMPROPER INACTION ON THE PART OF THE SAID MINISTER TO PERFORM HIS STATUTORY DUTY UNDER THE SAID SECTION 40 OF THE FOIA BETWEEN CHANDRESH SHARMA APPLICANT AND DR. LENNY SAITH MINISTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND INFORMATION RESPONDENT ************************ JUDGMENT Page 1 of 22 Before the Honourable Mr. Justice V. Kokaram Appearances: Mr. Anand Ramlogan, Ms. J.Kublalsingh, and Mr. N Lalbeharry, instructed by Mr. S. Ramnanan and for the Applicant Mr. Fyard Hosein S.C. and Ms. Bridgemohansingh for the Respondent 1. INTRODUCTORY FACTS Before the Court is an application for judicial review filed on 1st June 2005 involving an aspect of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). It involves the obligation of the Minister of Public Administration and Information, the Respondent, to prepare a report on the operation of the FOIA for any and/or all of the years of 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004 and cause a copy of same to be laid before each House of Parliament pursuant to section 40 of the FOIA.1 Mr Chandresh Sharma, the Applicant, acting in his capacity as a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago, Opposition Member of Parliament and taxpayer, wrote the Respondent by letter dated 16th February 2005 making the following inquiries: “I write in my capacity as a citizen, Opposition Member of Parliament and taxpayer. -

Wednesday October 17, 2012

607 Leave of Absence Wednesday, October 17, 2012 SENATE Wednesday, October 17, 2012 The Senate met at 10.00 a.m. PRAYERS [MADAM VICE-PRESIDENT in the Chair] LEAVE OF ABSENCE Madam Vice-President: Hon. Senators, I have granted leave of absence to Sen. James Lambert who is out of the country, and Sen. Elton Prescott SC, who is ill. We will have to return to this item when we do get the instruments of appointment at a later point in the debate. APPROPRIATION (FINANCIAL YEAR 2013) BILL, 2012 [Third Day] Order read for resuming adjourned debate on question [October 15, 2012]: That the Bill be now read a second time. Question again proposed. Madam Vice-President: Those who have spoken on Monday, October 15, 2012: Sen. The Hon. Larry Howai, Minister of Finance and the Economy, the mover of the Motion, Sen. Dr. Lester Henry, Sen. Subhas Ramkhelawan, Sen. The Hon. Kevin Ramnarine, Sen. Shamfa Cudjoe, Sen. Corinne Baptiste-Mc Knight, Sen. The Hon. Christlyn Moore, Sen. Helen Drayton, Sen. The Hon. Jamal Mohammed and Sen. James Lambert. Those who have spoken on Tuesday, October 16, 2012: Sen. The Hon. Vasant Bharath, Sen. Terrence Deyalsingh, Sen. Dr. Rolph Balgobin, Sen. The Hon. Fazal Karim, Sen. Faris Al-Rawi, Sen. Dr. Victor Wheeler, Sen. The Hon. Emmanuel George, Sen. Deon Isaac, Sen. Dr. Lennox Bernard, Sen. The Hon. Embau Moheni and Sen. The Hon. Devant Maharaj. Any Senator wishing to join the debate may do so at this time. The Attorney General (Sen. The Hon. Anand Ramlogan SC): Thank you very much, Madam Vice-President. -

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago in the High Court Of

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Port of Spain Claim No. CV2017–03276 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR REDRESS PURSUANT TO SECTION 14 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO FOR THE CONTINUING VIOLATION OF CERTAIN RIGHTS GUARANTEED UNDER SECTION 4 BETWEEN SHARON ROOP CLAIMANT AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO DEFENDANT Before the Honourable Madame Justice Margaret Y. Mohammed Date of delivery: November 9, 2018 APPEARANCES: Mr. Anand Ramlogan SC, Mr. Gerald Ramdeen, Ms. Chelsea Stewart instructed by Mr. Robert Abdool‐Mitchell Attorneys at law for the Claimant. Ms. Tinuke Gibbons‐Glenn, Mr. Stefan Jaikaran and Ms. Candice Alexander instructed by Ms. Svetlana Dass Attorneys at law for the Defendant. Page 1 of 65 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Introduction 4 Whether the Claimant’s rights under section 4(h) of the Constitution 6 have been infringed? The Applicable Test 11 Does The Limitation of the Fundamental Right Pursue a Legitimate Aim? 14 The Test for Section 4(h) 16 Honest Conviction 19 Legitimate Nexus 19 The Hijab 21 Floodgates 25 Neutrality 26 The United States of America 26 The European Court of Human Rights and The European Court of Justice 27 The United Nations Human Rights Committee 33 The Caribbean Perspective 34 The History of Religion in Trinidad and Tobago 37 Interpreting the Constitution 39 Whether Regulation 121 D of the Police Service Act is Unconstitutional 43 The Privy Council Approach 45 The CCJ’s Approach 49 The Emerging Approach in Trinidad and Tobago 53 Interpreting Section 6(1) (b) of the Constitution 54 Has the Claimant suffered any damages? 60 Page 2 of 65 Is the Instant Action an Abuse of Process? 60 Conclusion 61 Order 62 Page 3 of 65 JUDGMENT Introduction 1. -

Vishnu Jugmohan V Teaching Service Commission

REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO CLASSIFICATION : ORGINATING SUMMONS IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE SUB-REGISTRY, SAN FERNANDO H.C.A. NO. 1055 OF 2004 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY VISHNU JUGMOHAN OF NO. 805 ST. CROIX ROAD LENGUA VILLAGE, BARRACKPORE FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW AS OF RIGHT PURSUANT TO SECTION 39 OF THE FREEDOM ON INFORMATION ACT 1999 (AS AMENDED) (“THE SAID ACT) AND THE MATTER OF THE ILLEGAL AND/OR UNLAWFUL FAILURE AND/OR REFUSAL BY THE TEACHING SERVICE COMMISSION AND/OR THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION TO MAKE A DECISION ON THE APPLICANT APPLICATION OR REQUEST FOR CERTAIN INFORMATION PURSUANT TO THE PROVISIONS OF THE SAID ACT AND IN THE MATTER OF THE ILLEGAL AND/OR UNLAWFUL DENIAL OF ACCESS TO AND/OR PROVISIONS OF COPIES OF THE DOCUMENTS REQUESTED VIA AN APPLICATION UNDER THE SAID ACT DATED 14TH DAY OF APRIL, 2004 AND IN THE MATTER OF THE UNREASONABLE DELAY ON THE PART OF THE RESPONDENT IN MAKING A DECISION ON THE APPLICANT’S REQUEST FOR CERTAIN INFORMATION PURSUANT TO AND UNDER THE PROVISIONS OF THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT AND/OR IN PROVIDING THE REQUESTED INFORMATION TO THE APPLICANT 1 BETWEEN VISHNU JUGMOHAN APPLICANT AND TEACHING SERVICE COMMISSION RESPONDENT ************************ JUDGMENT Before the Honourable Mr. Justice V. Kokaram Appearances: Mr. Anand Ramlogan, and Ms. J. Furlonge for the Applicant Mr. Sasha Bridgemohansingh and Ms. S. Sharma for the Respondent 1. THE FOIA APPLICATION: 1.1 Mr Vishnu Jugmohan, the Applicant, a workshop attendant employed at the Moruga Composite School for over 13 years, made a request pursuant to section 13 of the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) of the Ministry of Education1 for the following documents: 1. -

Press and Politics in Trinidad and Tobago: a Study of Five Electoral Campaigns Over Ten Years, 2000-2010 Bachan-Persad, I

Press and politics in Trinidad and Tobago: A study of five electoral campaigns over ten years, 2000-2010 Bachan-Persad, I. Submitted version deposited in CURVE October 2014 Original citation & hyperlink: Bachan-Persad, I. (2012) Press and politics in Trinidad and Tobago: A study of five electoral campaigns over ten years, 2000-2010. Unpublished Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to third party copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Press and politics in Trinidad and Tobago: A study of five electoral campaigns over ten years, 2000- 2010 I. Bachan-Persad Doctor of Philosophy [Media and Politics] 2012 Press and politics in Trinidad and Tobago: A study of five electoral campaigns over ten years, 2000- 2010 By Indrani Bachan-Persad A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy [Media and Politics] at Coventry University, UK August 2012 The work contained within this document has been submitted by the student in partial fulfilment of the requirement of their course and award i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the role of the press in five political campaigns in Trinidad and Tobago, over a ten year period, from 2000 to 2010. -

1 2013 Opening Speech Address by the Honourable

2013 OPENING SPEECH ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE AT THE OPENING OF THE 2013/2014 LAW TERM ON THE 16TH DAY OF SEPTEMBER 2013 Your Excellency Mr. Anthony Thomas Aquinas Carmona O.R.T.T, S.C. President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago and Mrs. Carmona The Honourable Kamla Persad-Bissessar, S.C. Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, and Dr Bissessar Senator Timothy Hamel-Smith, President of the Senate The Honourable Wade Mark, Speaker of the House of Representatives and Mrs Mark Senator the Honourable Anand Ramlogan, Attorney General Senator The Honourable Emmanuel George, Minister of Justice The Honourable Prakash Ramdar, Minister of Legal Affairs Other Members of the Cabinet of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Mr Orville London, Chief Secretary of the Tobago House of Assembly The Honourable Keith Rowley, Leader of the Opposition and Mrs Rowley Members of the Diplomatic Corps The Right Honourable Sir Charles Denis Byron, President of the Caribbean Court of Justice, and Lady Byron Honourable Justices of Appeal and Judges and Masters of the Supreme Court of Trinidad and Tobago Heads of Religious Bodies Chairmen and Members of Superior Courts of Record Members of Parliament Her Worship Marcia Ayers Caesar, Chief Magistrate 1 Members of the Legal Fraternity, the business sector, religious organisations and civil society Other specially invited guests Members of the Media Distinguished ladies and gentlemen all. The format of today’s address may be different from what some of you may have come to expect based on past presentations. I will not be reporting in detail on grand projects completed or to be launched although there are successes to report. -

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago in the High Court Of

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. CV2020-02237 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY SIEWNARINE RAMSARAN (FIRE SERVICE NUMBER 1712) FOR AN ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER UNDER PART 56 OF THE CIVIL PROCEEDINGS RULES 1998 (AS AMENDED) AND IN THE MATTER OF THE UNFAIR TREATMENT OF THE CLAIMANT BY REASON OF THE FAILURE AND/OR REFUSAL BY THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION TO PROVIDE A STATEMENT OF REASONS FOR BYPASSING HIM FOR ACTING APPOINTMENT AS DEPUTY CHIEF FIRE OFFICER AND IN THE MATTER OF THE UNEQUAL TREATMENT OF THE APPLICANT/CLAIMANT IN BREACH OF HIS RIGHT AND/OR LEGITIMATE EXPECTATION TO BE FAIRLY CONSIDERED FOR ACTING APPOINTMENT TO THE RANK OF DEPUTY CHIEF FIRE OFFICER IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION REGULATIONS AND IN THE MATTER OF THE VIOLATION OF THE CLAIMANT’S CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO EQUALITY OF TREATMENT FROM A PUBLIC AUTHORITY IN THE EXERCISE OF ITS FUNCTIONS UNDER SECTION 4(d) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO ACT NO. 4 OF 1976 BETWEEN SIEWNARINE RAMSARAN (FIRE SERVICE NUMBER 1712) CLAIMANT AND Page 1 of 57 THE CHIEF FIRE OFFICER FIRST DEFENDANT AND THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION SECOND DEFENDANT AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO THIRD DEFENDANT Before the Honourable Madame Justice Margaret Y Mohammed Date of Delivery 28 June 2021 APPEARANCES Mr Anand Ramlogan SC, Ms Jayanti Lutchmedial and Ms Renuka Rambhajan instructed by Ms Alana Rambaran Attorneys at law for the Claimant. Ms Nadine Nabie, Ms Nicol Yee Fung and Ms Zara Smith instructed by Ms Avaria Niles and Ms Radha Sookdeo Attorneys at law for the Defendants.