Urban Design Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2014 Incorporating Islington History Journal

Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Vol 4 No 3 Autumn 2014 incorporating Islington History Journal War, peace and the London bus The B-type London bus that went to war joins the Routemaster diamond jubilee event Significants finds at Caledonian Parkl Green plaque winners l World War 1 commemorations l Beastly Islington: animal history l The emigrants’ friend and the nursing pioneer l The London bus that went to war l Researching Islington l King’s Cross aerodrome l Shoreditch’s camera obscura l Books and events l Your local history questions answered About the society Our committee What we do: talks, walks and more Contribute to this and contacts heIslington journal: stories and President Archaeology&History pictures sought RtHonLordSmithofFinsbury TSocietyishereto Vice president: investigate,learnandcelebrate Wewelcomearticlesonlocal MaryCosh theheritagethatislefttous. history,aswellasyour Chairman Weorganiselectures,tours research,memoriesandold AndrewGardner,andy@ andvisits,andpublishthis photographs. islingtonhistory.org.uk quarterlyjournal.Wehold Aone-pagearticleneeds Membership, publications 10meetingsayear,usually about500words,andthe and events atIslingtontownhall. maximumarticlelengthis CatherineBrighty,8 Wynyatt Thesocietywassetupin 1,000words.Welikereceiving Street,EC1V7HU,0207833 1975andisrunentirelyby picturestogowitharticles, 1541,catherine.brighteyes@ volunteers.Ifyou’dliketo butpleasecheckthatwecan hotmail.co.uk getinvolved,pleasecontact reproducethemwithout -

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal July 2018 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Alison Bennett, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 2/8/18 Reviser(s): Alison Bennett Date of last revision: 31/8/18 Date Printed: Version: 2 Status: Summary of Changes: Circulation: Required Action: File Name/Location: Approval: (Signature) 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 5 3 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers .................................................................................. 7 4 The London Borough of Islington: Historical and Archaeological Interest ....................... 9 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Prehistoric (500,000 BC to 42 AD) .......................................................................... 9 4.3 Roman (43 AD to 409 AD) .................................................................................... 10 4.4 Anglo-Saxon (410 AD to 1065 AD) ....................................................................... 10 4.5 Medieval (1066 AD to 1549 AD) ............................................................................ 11 4.6 Post medieval (1540 AD to 1900 AD).................................................................... 12 4.7 Modern -

73 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

73 bus time schedule & line map 73 Stoke Newington - Oxford Circus View In Website Mode The 73 bus line (Stoke Newington - Oxford Circus) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oxford Circus: 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM (2) Stoke Newington: 12:00 AM - 11:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 73 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 73 bus arriving. Direction: Oxford Circus 73 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Oxford Circus Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:05 AM - 11:57 PM Monday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Stoke Newington Common (K) Tuesday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Stoke Newington High Street (U) 128 Stoke Newington High Street, London Wednesday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM William Patten School (V) Thursday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM 37A Stoke Newington Church Street, London Friday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM Abney Park (W) Saturday 12:04 AM - 11:56 PM 86 Stoke Newington Church Street, London Stoke Newington Town Hall (W) 181 Stoke Newington Church Street, London 73 bus Info Barbauld Road (S) Direction: Oxford Circus 184 Albion Road, London Stops: 33 Trip Duration: 49 min Clissold Crescent (NA) Line Summary: Stoke Newington Common (K), Clissold Crescent, London Stoke Newington High Street (U), William Patten School (V), Abney Park (W), Stoke Newington Town Green Lanes (NB) Hall (W), Barbauld Road (S), Clissold Crescent (NA), 40-41 Newington Green, London Green Lanes (NB), Newington Green (NE), Beresford Road (CA), Balls Pond Road (CB), Essex Road / Newington Green (NE) Marquess Road (CG), Northchurch Road (EH), Essex 20 Newington -

Development Management Policies June 2013

Islington’s Local Plan: Development Management Policies June 2013 Adopted 27 June 2013 Contents List of policies 3 1 Introduction 7 2 Design and heritage 11 3 Housing 30 4 Shops, culture and services 57 5 Employment 84 6 Health and open space 95 7 Energy and environmental standards 111 8 Transport 121 9 Infrastructure and implementation 133 10 Monitoring 138 Appendix Appendix 1 Local Views 146 Appendix 2 Primary and Secondary Frontages 152 Appendix 3 Local Shopping Areas 155 Appendix 4 Open spaces, SINCs and adventure playgrounds 160 Appendix 5 Transport Assessments and Travel Plans 168 Appendix 6 Cycling 172 Appendix 7 Archaeological Priority Areas and Scheduled Monuments 176 Appendix 8 Rail Safeguarding Areas 185 Appendix 9 Heritage 191 Development Management Policies - Adoption 2013 Islington Council Contents Appendix 10 Noise Exposure Categories and standards 197 Appendix 11 Marketing and market demand evidence 200 Appendix 12 Landscape plans 203 Appendix 13 Glossary 205 Islington Council Development Management Policies - Adoption 2013 List of policies List of policies Policy number Policy name Page Chapter 2: Design and heritage DM2.1 Design 11 DM2.2 Inclusive Design 16 DM2.3 Heritage 18 DM2.4 Protected views 23 DM2.5 Landmarks 24 DM2.6 Advertisements 25 DM2.7 Telecommunications and utilities 26 Chapter 3: Housing DM3.1 Mix of housing sizes 29 DM3.2 Existing housing 31 DM3.3 Residential conversions and extensions 31 DM3.4 Housing standards 34 DM3.5 Private outdoor space 42 DM3.6 Play space 45 DM3.7 Noise and vibration (residential -

Historic Maps and Plans of Islington (1553-1894)

Mapping Islington Historic maps and plans of Islington (1553-1894) Mapping Islington showcases a selection of maps and plans relating to the three former historic parishes that now form the London Borough of Islington. Maps are a window into the past. They provide historical evidence and offer a valuable insight to bygone streets, industries and landscapes. They are also an important source for local history research and help us to understand the development and changes that have shaped the Plan of parish of St Mary, character and identity of our borough. Islington and its environs. Surveyed by Edward Baker The display’s earliest map dates from mid-16th Century (c.1793) when Islington was a rural village outside of the City of London, ending with a survey published during the late-Victorian era when the area had become a densely populated and urbanised district of north London. The London Borough of Islington was formed in 1965 when the Metropolitan boroughs of Islington and Finsbury merged. In 2019 the borough covers an area of 14.86 km2 and stretches from Highgate in the north to the City of London borders in the south. Before 1900 Islington was historically administered in three distinct civil parishes: • St Mary Islington (north and central) • St James Clerkenwell (south-west) • St Luke Old Street (south-east) The Copperplate Map of London, c.1553-59 Moorfields The Copperplate Map of London is a large-scale plan Frans Franken of the city and its immediate environs. It was originally Museum of London created in 15 printed copperplate sections, of which only three are still in existence. -

Buses from Parliament Hill Fields

Buses from Parliament Hill Fields 4 C11 ARCHWAYARCHWAY Archway Key 214 MacDondald Road Highgate Village Ø— Connections with London Underground Highgate School HIGHGATEHIGHGATE VILLAGEVILLAGE Archway Highgate Hill u Connections with London Overground Highgate Hill West R Pond Square Connections with National Rail Whittington Hospital  Connections with river boats Highgate Hill West HQ Merton Lane ALA AVE. Highgate D MAGD A Cemetery R HJ OAKESHOTT AVENUE HN T Highgate Hill West M . O ST U Oakeshott Avenue E N BREDG O T N YD H AR MAKEPEACE AVENUE A HC A R L P ROAD A R R S HAR HL K ’ TE R GRA O VE N S A ANGBOURNE AVE. I PARK L E D H HB A H H C I I HM L G W L H S G HD HK A A D T GJ A E RO Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus The yellow tinted area includes every R NS O BA !A A AL D service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop in the bus stop up to one-and-a-half miles GK T D S A 1 2 3 O from Parliament Hill Fields. Main stops R 4 5 6 street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). GH TA N TK are shown in the white area outside. GL W DO FT O YO D GM CR A RK RISE R T D M H OA O I R U G H T H G D GF A A ER O P T I R A E R U D R R LA YN K O GN W A ET H GE D I H L C L LISSENDEN GARDENS SE Dartmouth Park Road Route finder Junction Road HOLLOWAYHOLLOWAY BRENTBRENT CROSSCROSS GORDON ROAD HOU Day buses including 24-hour services Tufnell Park Tufnell Park Road C11 Brent Cross Shopping Centre Gordon House Road Dalmeny Road Bus route Towards Bus stops Highgate Road Tufnell Park Road Gospel Oak Lady Somerset Road Tufnell -

Fully Let Prime London Investment Opportunity 21 & 29-31 Essex Road Islington, London N1 Investment Summary

FULLY LET PRIME LONDON INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 21 & 29-31 ESSEX ROAD ISLINGTON, LONDON N1 INVESTMENT SUMMARY Located in Islington, one of the most affluent London Boroughs. Situated on Essex Road which benefits from a variety of pubs, bars, shops and restaurants whilst in close proximity to Islington Green, Upper Street and Angel Underground Station. Nearby occupiers include Tesco Express, Reiss, Waterstones, Côte Brasserie, The Gym Group, Nuffield Health & Fitness, Barrio, Wenlock & Essex and the Old Queens Head. Comprises two ground floor units held on two separate long leasehold interests at fixed peppercorn rents. Fully let to Brewdog (underlet to Essex House) and Floatworks producing a total rent passing of £190,000 per annum (any outstanding rent free and annual stepped rents to be topped up). Attractive Average Weighted Unexpired Lease Term of 14.7 years to expiry (11.6 years to break). Seeking offers of£3,244,000 (Three Million, Two Hundred and Forty Four Thousand Pounds), Subject to Contract and exclusive of VAT, reflecting aNet Initial Yield of 5.50%, allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.48%. Situated on Essex Road which benefits from a variety of pubs, bars, shops and restaurants whilst in close proximity to Islington Green, Upper Street and Angel Underground Station. 21 & 29-31 ESSEX ROAD // ISLINGTON // LONDON N1 PRIME LONDON INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 2 LOCATION SITUATION London Borough of Islington, one of London’s most vibrant and The subject property is prominently situated in the heart of Islington affluent conurbations, is located approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) north on the western side of Essex Road at its junction with Gaskin Street. -

Penthouses Collection 8 Esther Anne Place

Penthouses Collection 8 Esther Anne Place ISLINGTON SQUARE 1 Contents 02 38 The Place to Live Historical The Place that Lives Ambassadors 04 40 The Pinnacle Premium of London Living Living 14 72 In and Around Material Palette Islington Square and Specifications 34 78 The Centre The Space to Live of Things The Space to Grow 36 104 Explore the Contact Whole of London 2 ISLINGTON SQUARE The Place to Live The Place that Lives Islington has a fascinating and diverse history. An exciting mix of independent businesses and boutiques, cultural venues and creative hubs makes it one of London’s most celebrated areas. In the heart of the community is Islington Square, a development that builds on the richness and variety of this neighbourhood. At the centre of the scheme is an Edwardian former Royal Mail sorting office, beautifully restored to its former grandeur and importance by CZWG Architects. Above grand new buildings, high arcades and a tree-lined boulevard, they have created fantastic apartments for living, arranged around calming internal landscaped courtyards. This vibrant addition to Islington includes a prestigious collection of shops, cafés and restaurants alongside warehouse-style apartments. There will be a luxury cinema, The Lounge by Odeon; a 40,000 square foot Third Space premier gym and a new landmark public art commission. It is a city within a city. At the heart of CZWG Architects’ stunning designs for Islington Square 2 THE SCHEME is the lovingly restored Edwardian former sorting office building. ISLINGTON SQUARE 3 The Pinnacle of London Living CZWG Architects are renowned for their outstanding schemes that astound and inspire. -

For Sale with Vacant Possession

17027 10/12/04 10:25 AM Page 1 H A L H T E A D O M R O T EE N STR I G N N L O F T I D URY R G SB BAR N O Freehold Central A N London Building F A E O D T O W R E R D C D RO E SS A S R T D N U E O SH V E N T E R I C H M O N D A X O PP A ER Y R T S O R E R N R D O O O A O T T D A RG S A AS E For Sale ST KIN E H R D BERTON R R O THE E ST R L S PA T R P C K E K 322 S O G I R NG P E T D EN ON H A G E N O N C O P E N ST U T S R Y N S T E E H R P O B E R T T G S IG W E E O N N T L U R I L Y R S A I P P A B R E E A A T W S E D I V R D Y C O With Vacant Possession N I HA ’S R RLT T ON R F L P N R E L S R T E T A A S H R R K O T H W B E WYNFORD RD G E S O L I E G D P D H A R U T N O E E C B ET E AN N K R E O R S O N A P T WHARFDALE RD EL M E L S D P CHA P R O A D T B N H L U W E O E VIN Y C ENT H E A N ION TE S ITE L ST P WH OL R A T ST R R AL S R E C E E T NEG C G City Basin R E DO Angel T T R S F R King’s E I E R A O L L T Cross C A D H D R O A R E E M O L L S V I A N S G S S T O D E N A T T P O C R M I E D S T W as A Y E O G W W T R A E L N R King’s Cross E E K O L J L B A Thameslink E K L L L O I Y Y N R R E G S A H O ’ U A ’ T S S T D S N N ST ST R R N E E CER TO C K N C E V SPE J A R A B A E T O E R R E U S D T S T S Y Y O D R O R O L R V E Old D I L E A E AD L Stre N B E S T D KI S S S NN AL N E CIV O R ER T F R S P A T R R T R S E E E R IN T T S E R G E D R D T O U O L N N E O Russell A E E T V E Square E D A T R T S Y D R R E D O B A L F E E L L R O I S U E N W G O R K R C L E CONTACT INFORMATION Alex Bard or David Baroukh David Baroukh -

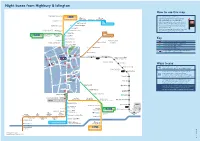

Night Buses from Highbury & Islington

Night buses from Highbury & Islington Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 43 from stops A, F, P, R, S Seven Sisters Broad Lane Tottenham Hale Colney Hatch Lane N41 West Green Road from stops A, F, P, R, S Night buses fromMuswell Hill BroadwayHighburyN41 Turnpike Lane & Islington 43 Hornsey HIGHGATE Highgate Crouch End Broadway Friern Barnet Halliwick Park Hornsey Rise N19 43 271 Highgate Village Whittington from stops C, F, P, R South Grove Hospital fromArchway stops A, F, P, R, S from stops A, H, L, S Seven Sisters Broad Lane Tottenham FinsburyHale Park Colney Hatch Lane Upper Holloway N41 43 271 N41 West Green Road from stops A, F, P, R, S RY Holloway Nag’s Head Blackstock Road HOLMuswellLO WHill ABroadwayY N41 Turnpike Lane PARK 43Holloway RoadHornsey L I V Highbury Park S HOLLOWAYT Crouch End Broadway E Highgate E N19 HIGHGATE Highbury C R ET P Fields AM O Hornsey Rise GH O N19 IN L R HighgateE VillageAD Whittington 271 SH R NG Highbury Grove from stops C, F, P, R RO O SouthW Grove Hospital LO ROADArchwayB A FUR AD RSICA STRE from stops A, H, L, S E D RO HIGHBURY PLA Finsbury Park S CO R T Highbury C O B T A Upper Holloway St. Paul’s Road Balls Pond Road A O & Islington U AD D BRIDE S ’S RO Dalston Junction R 43 271 N41 T. PAUL N S N277 forR DalstonY Kingsland E U Holloway Nag’s Head X D C Blackstock Road Highbury O HOLLO WAY PARK L Corner M UNDE S AR Q HIGHBURYHolloway Road P T DALSTON Graham Road STATIONF RD O L T N I W V L E Highbury Park V AYCT S HOLLOWAYO CK E R N19 E OAD E R R HighburyH C O R STR EE T ETA P T Fields S J D Hackney Central AM O G OFFORDGH O R C RIN L E A E P N AD R D G Highbury Grove SH P RO N O HACKNEY O A LO ROAD B U W A N UR O RSICA STRE Lauriston Road D F AD B N277 E R HIGHBURY PLA RO S COU R T Highbury R L C O B T A Y St. -

Buses from Mildmay Park, Balls Pond Road

Buses from Mildmay Park, Balls Pond Road Palmers Green Wood Turnpike Harringay HARRINGAY Key North Circular Road Green Lane Green Lanes 76 Tottenham Hale N38 56 Ø— Connections with London Underground 141 WOOD Manor House Tottenham Walthamstow Central Whipps Cross u Connections with London Overground Town Hall Roundabout Green Lanes GREEN Seven Sisters R Connections with National Rail Gloucester Drive Leyton Green Lanes BakerÕs Arms Î Connections with Docklands Light Railway Myddleton Avenue TOTTENHAM South Tottenham Lea Bridge Road  Green Lanes Markhouse Road Connections with river boats Brownswood Road Stamford Hill Broadway Green Lanes 38 Clapton Kings Crescent Estate Stoke Newington Lea Bridge Roundabout Green Lanes CLAPTON Riversdale Road Stoke Newington High Street STOKE Garnham Street Clapton Green Lanes Pond A Stoke Newington Church Street NEWINGTON Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus Stoke Newington High Street The yellow tinted area includes every Green Lanes Brooke Road !A Petherton Road Clapton service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop in the bus stop up to one-and-a-half miles Pembury Road GirlsÕ Academy 1 2 3 from Mildmay Park (Balls Pond Road). Stoke Newington 4 5 6 street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). Green Lanes Police Station Downs Park Road Main stops are shown in the white Aden Grove area outside. Newington Green 21 Stoke Newington Road Lower Clapton Road Amhurst Road Glenarm Road Newington Green Dalston Lane Mildmay Road Stoke Newington Road Hackney Baths Princess May Road Mare Street/ Dalston Lane Narrow Way Kingsland High Street Cecilia Road/ M LK Rio Cinema Greenacre Court A MILDMAY I Route finder L GROVE W D S OUTH S Hackney Downs M ’ Dalston Kingsland Y A R N Day buses including 24-hour services Y E BL H Kingsland High Street M P G Dalston Junction Dalston Lane I A HACKNEY LD BB IN Bus route Towards Bus stops M AY ST. -

Buses from Highbury & Islington

Buses from Highbury & Islington Friern Barnet Muswell Hill Archway Holloway Road 393 Library Broadway for Whittington Hospital Elthorne Road Upper Holloway Clapton Pond 43 Colney Highgate CLAPTON Hatch Holloway Road Wedmore Street Clapton Lane 4 Dartmouth Park Hill Key Tufnell Tufnell FINSBURY Upper Clapton HIGHGATE Park Road Park Road Holloway Road Manor Gardens Mount Pleasant Hill Tufnell Park Carleton Road Odeon Cinema Highgate Village Seven Sisters Road Seven Sisters Road PARK Warwick Grove Ø— South Grove NagÕs Head Durham Road Connections with London Underground 19 Upper Clapton 271 Holloway Road Seven Sisters Road Seven Sisters Road Northwold Estate u Tufnell Park Road 153 Finsbury Park Connections with London Overground Hornsey Road Fonthill Road Interchange (not 4) Tollington Road Cazenove Road R Holloway Road/ Isledon Road Connections with National Rail Caledonian Road Holloway Berriman Road Stoke Newington Freegrove Road Camden Road Îv NagÕs Head Connections with Docklands Light Railway North Road Isledon Road Pleasance Theatre Tollington Road Finsbury Park Stoke Newington Church Street Caledonian Road Caledonian Road Hornsey Road/ Fonthill Road Seven Sisters Road Rock Street Bouverie Road  Connections with river boats Hillmarton Road Camden Road Sobell Centre Stoke Newington Church Street Clissold Road Blackstock Road York Way North Road HOLLOWAY Holloway Road Stoke Newington Church Street Camden Park Road Goodinge Health Centre Monsell Road Holloway Road for Arsenal Emirates Stadium Clissold Crescent Camden Road Holloway Road