The Case of Kolwezi in the DRC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Files, Country File Africa-Congo, Box 86, ‘An Analytical Chronology of the Congo Crisis’ Report by Department of State, 27 January 1961, 4

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/113873/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Marsh, Stephen and Culley, Tierney 2018. Anglo-American relations and crisis in The Congo. Contemporary British History 32 (3) , pp. 359-384. 10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 file Publishers page: http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 <http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 ARTICLE Congo, Anglo-American relations and the narrative of � decline: drumming to a diferent beat Steve Marsh and Tia Culley AQ2 AQ1 Cardiff University, UK� 5 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The 1960 Belgian Congo crisis is generally seen as demonstrating Congo; Anglo-American; special relationship; Anglo-American friction and British policy weakness. Macmillan’s � decision to ‘stand aside’ during UN ‘Operation Grandslam’, espe- Kennedy; Macmillan cially, is cited as a policy failure with long-term corrosive efects on 10 Anglo-American relations. -

FROM COERCION to COMPENSATION INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES to LABOUR SCARCITY in the CENTRAL AFRICAN COPPERBELT African Economic

FROM COERCION TO COMPENSATION INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES TO LABOUR SCARCITY IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN COPPERBELT African economic history working paper series No. 24/2016 Dacil Juif, Wageningen University [email protected] Ewout Frankema, Wageniningen University [email protected] 1 ISBN 978-91-981477-9-7 AEHN working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. The papers have not been peer reviewed, but published at the discretion of the AEHN committee. The African Economic History Network is funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Sweden 2 From Coercion to Compensation Institutional responses to labour scarcity in the Central African Copperbelt* Dácil Juif, Wageningen University Ewout Frankema, Wageningen University Abstract There is a tight historical connection between endemic labour scarcity and the rise of coercive labour market institutions in former African colonies. This paper explores how mining companies in the Belgian Congo and Northern Rhodesia secured scarce supplies of African labour, by combining coercive labour recruitment practices with considerable investments in living standard improvements. By reconstructing internationally comparable real wages we show that copper mine workers lived at barebones subsistence in the 1910s-1920s, but experienced rapid welfare gains from the mid-1920s onwards, to become among the best paid manual labourers in Sub-Saharan Africa from the 1940s onwards. We investigate how labour stabilization programs raised welfare conditions of mining worker families (e.g. medical care, education, housing quality) in the Congo, and why these welfare programs were more hesitantly adopted in Northern Rhodesia. By showing how solutions to labour scarcity varied across space and time we stress the need for dynamic conceptualizations of colonial institutions, as a counterweight to their oft supposed persistence in the historical economics literature. -

Identity, Territory, and Power in the Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS SOUTH KIVU IDENTITY, TERRITORY, AND POWER IN THE EASTERN CONGO RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT South Kivu Identity, territory, and power in the eastern Congo KOEN VLASSENROOT Published in 2013 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1DF, United Kingdom PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya THE USALAMA PROJECT The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square, and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political, and economic development. THE AUTHOR Koen Vlassenroot is Professor of Political Science and director of the Conflict Research Group at the University of Ghent. He is associated to the Egmont Institute and a RVI fellow. He co-authored Conflict and Social Transformation in Eastern DR Congo (2004) and co-edited The Lord’s Resistance Army: Myth or Reality? (2010). He is the lead researcher on the DRC for the Justice and Security Research Programme. CREDITS RVI ExECUTIVE DIRECTOR: John Ryle RVI PROgRAMME DIRECTOR: Christopher Kidner RVI USALAMA PROJECT DIRECTOR: Jason Stearns RVI USALAMA DEPUTY PROJECT DIRECTOR: Willy Mikenye RVI Great LAKES PROgRAMME MANAgER: Michel Thill RVI Information OFFICER: Tymon Kiepe EDITORIAL consultant: Fergus Nicoll Report DESIgN: Lindsay Nash Maps: Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix PRINTINg: Intype Libra Ltd., 3/4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London SW19 4HE ISBN 978-1-907431-25-8 COVER CAPTION Congolese woman carrying firewood in the hills of Minembwe, South Kivu (2012). -

Tangled! Congolese Provincial Elites in a Web of Patronage

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Tangled! Congolese provincial elites in a web of patronage Working paper 64 Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert January 2019 Written by Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert SLRC publications present information, analysis and key policy recommendations on issues relating to livelihoods, basic services and social protection in conflict-affected situations. This and other SLRC publications are available from www.securelivelihoods.org. Funded by UK aid from the UK Government, Irish Aid and the EC. Disclaimer: The views presented in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies or represent the views of Irish Aid, the EC, SLRC or our partners. ©SLRC 2018. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from SLRC for their own publications. As copyright holder SLRC requests due acknowledgement. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Overseas Development Institute (ODI) 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 3817 0031 F +44 (0)20 7922 0399 E [email protected] www.securelivelihoods.org @SLRCtweet Cover photo: Provincial Assembly, Lualaba. Lisa Jené, 2018 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). B About us The Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) is a global research programme exploring basic services, livelihoods and social protection in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Funded by UK Aid from the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID), with complementary funding from Irish Aid and the European Commission (EC), SLRC was established in 2011 with the aim of strengthening the evidence base and informing policy and practice around livelihoods and services in conflict. -

IMCK Newsletter 17.3.Pages

INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIEN DU KASAI !1 OFINSTITUT MEDICAL!5 CHRETIEN DU KASAI B.P. 205 KANANGA B.P. 205 KANANGA INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIENREPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU DUKASAI CONGO REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Christian Medical Institute Hôpitalof – theEcole d’infirmiers Kasai – Ecole de laborantins - Serving – Service de santé communautairein Central - Service d’ophtalmologie Congo Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage Hôpital – Ecole d’infirmiers – Ecole de laborantins – Service de santé communautaire - Service d’ophtalmologie E-mail : [email protected] Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage B. P. 205 Kananga, Republic Democratic du Congo ; Email: [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them where A Periodic Newsletter operational needs are Issuethe most desperate. No. 41 But ifJanuary you cannot (and - thatMarch is understandable, 2017 of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them whereA considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider operational needs are the most desperate. But if you cannot (and that is understandable, designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider The current conflict in the Kasai has needs.I askedFor example the new: Specify IMCK money Administrator, for medicines and Kastin medical Katawa, supplies; Specifyto describe money designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational added new suffering and danger. -

GLENCORE: a Guide to the 'Biggest Company You've Never Heard

GLENCORE: a guide to the ‘biggest company you’ve never heard of’ WHO IS GLENCORE? Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trading company and 16th largest company in the world according to Fortune 500. When it went public, it controlled 60% of the zinc market, 50% of the trade in copper, 45% of lead and a third of traded aluminium and thermal coal. On top of that, Glencore also trades oil, gas and basic foodstuffs like grain, rice and sugar. Sometimes refered to as ‘the biggest company you’ve never heard of’, Glencore’s reach is so vast that almost every person on the planet will come into contact with products traded by Glencore, via the minerals in cell phones, computers, cars, trains, planes and even the grains in meals or the sugar in drinks. It’s not just a trader: Glencore also produces and extracts these commodities. It owns significant mining interests, and in Democratic Republic of Congo it has two of the country’s biggest copper and cobalt operations, called KCC and MUMI. Glencore listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2011 in what is still the biggest ever Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the stock exchange’s history, with a valuation of £36bn. Glencore started life as Marc Rich & Co AG, set up by the eponymous and notorious commodities trader in 1974. In 1983 Rich was charged in the US with massive tax evasion and trading with Iran. He fled to Switzerland and lived in exile while on the FBI's most-wanted list for nearly two decades. -

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

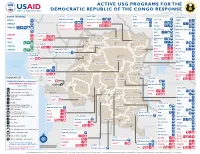

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

A Functional View of Linguistic Meaning

SWAHILI FORUM 22 (2015): vi-viii REVIEW Le swahili de Lubumbashi. Grammaire, textes, lexique [The Swahili from Lubumbashi. Grammar, texts, lexicon]. Aurélia Ferrari, Marcel Kalunga, and Georges Mulumbwa. 2014. Paris: Editions Karthala, 226 pp., ISBN 978-2-8111- 1130-4. Swahili is one of the four national languages of the Democratic Republic of Congo, together with Ciluba, Kikongo and Lingala, spoken by many millions mainly located in the eastern provinces. This interesting volume, appeared amongst the recent contributions to the Karthala series “Dictionnaires et Langues” (Dictionaries and Languages) directed by Henri Tourneux, is devoted 1 to a specific variety of Congolese Swahili, i.e. the Swahili of Lubumbashi , an originally vehicular and hexogen language which, as a result of the colonial language policy (Fabian 1986), has increasingly been spoken among urban residents, principally, but not exclusively, in oral 2 communication and performance , thus entering an ongoing process of vernacularisation and becoming the first language for a part of the population of the Katangese region. The work is a result of the collaboration between Aurélia Ferrari, specialist in emerging African language varieties, presently lecturer at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and two scholars from the DRC, experts in Swahili and Bantu languages, namely Marcel Kalunga, professor at the Universities of Lubumbashi and Kalemie, and Georges Mulumbwa, senior assistant in linguistics at the University of Lubumbashi. The book consists of three parts, the first -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Case 1:19-Cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79

Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79 TERRENCE COLLINGSWORTH (DC Bar # 471830) International Rights Advocates 621 Maryland Ave NE Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel: 202-543-5811 E-mail: [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiffs UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ________________ JANE DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 2, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA ROE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JAMES DOE 4, Individually and on Case No. CV: behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 5, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 6, Individually and on CLASS COMPLAINT FOR behalf of Proposed Class Members; INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AND JANE DOE 2, Individually and on DAMAGES behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 7, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JURY TRIAL DEMANDED JENNA DOE 8, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 9, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 10, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 11, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JANE DOE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 12, Individually and on 1 Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 2 of 79 behalf of Proposed Class Members; and JOHN DOE 13, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; all Plaintiffs C/O 621 Maryland Ave.