Art and Social Change: Naiza Khan Talks Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport MHFP

PLAYING HIDE AND SEEK How the shipping industry, protected by Flags Of Convenience, dumps toxic waste on shipbreaking beaches December 2003 table of contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Top twenty polluters 4 Chapter 2: Flags Of Convenience - A Cover for Ongoing Pollution 7 Chapter 3: Breakdown of profits and environmental and health costs of shipbreaking 9 Chapter 4: The need for a mandatory regime on shipbreaking 10 Conclusions 11 Appendix I: Details of end-of-life ships exported by twenty shipping companies in 2001-2003 13 Appendix II: Overview of ownership and flag state countries linked to exports of end-of-life ships in 2003 20 Appendix III: Investigation on the dumping of toxic waste and compliance to voluntary Industry Code of Practise on Shiprecycling 22 2 Introduction The recycling or breaking of end-of-life ships containing toxic substances is a polluting and highly dangerous industry. Five years ago this was news, today it is shameful. It is a shame on those responsible for this ongoing pollution; the ship- ping industry. It is a shame on the international community that has so far refused to take any real measures to prevent the pollution and dangers. A huge but unknown quantity of toxic substances has been exported to Asia over the past five years in end-of-life ships. Six hundred such ships are broken annually with none ever being cleaned by the owner prior to export, and only very few being cleaned by their owner prior to breaking. More than 3,000 ships, and the toxic waste in the ships, have been exported over the last five years to Asian shipbreaking yards. -

Weather Has the Bill Has Matter

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 227 JANUARY 21, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ A year of project completions ‘State of the City’ eyes present, future By JOYANNA LOVE spur even more economic growth a step closer toward the Spring Banner Senior Staff Writer FIRST OF 2 PARTS along the APD 40 corridor,” Rowland Branch Industrial Park becoming a said. reality. Celebrating the completion of some today. The City Council recently thanked “A conceptual master plan was long-term projects for the city was a He said the successes of the past state Rep. Kevin Brooks for his work revealed last summer, prepared by highlight of Cleveland Mayor Tom year were a result of hard work by city promoting the need for the project on TVA and the Bradley/Cleveland Rowland’s State of the City address. staff and the Cleveland City Council. the state level by asking that the Industrial Development Board,” “Our city achieved several long- The mayor said, “Exit 20 is one of Legislature name the interchange for Rowland said. term goals the past year, making 2015 our most visible missions accom- him. The interchange being constructed an exciting time,” Rowland said. “But plished in 2015. Our thanks go to the “The wider turn spaces will benefit to give access to the new industrial just as exciting, Cleveland is setting Tennessee Department of trucks serving our existing park has been named for Rowland. new goals and continues to move for- Transportation and its contractors for Cleveland/Bradley County Industrial “I was proud and humbled when I ward, looking to the future for growth a dramatic overhaul of this important Park and the future Spring Branch learned this year the new access was and development.” interchange. -

Gadani Ship-Breaking Yard

Gadani Ship-breaking Yard According to statistics released by environmental advocate, non-governmental agency Shipbreaking Platform, South Asian yards now offer about $450 per light displacement tonnage, or LDT, while Chinese yards offer only $210 and Turkish yards slightly better at $280 per LDT. It is also showed that a large container ship weighs in at almost 25,000 LDTs. That translates into $11.25 million in India, but only $7 million in Turkey and $5.25 million in China. Furthermore, Shipbreaking Platform releases a yearly survey on the industry. During 2017, the organization recorded, the industry internationally scrapped 835 ships, which totalled 20.7 million gross tons. That’s a substantial fall from 2016, when 27.4 million tons were scrapped. The number of scrapped ships has declined by greater than 30 percent from the boom days of 2012 to 2013. According to Mulinaris’s research, during 2017, saw the demolition of 170 bulk carriers, 180 general cargo ships, 140 containers, 140 tankers, 20 vehicle carriers, 14 passenger ships and 30-40 oil and gas related units, which include platforms and drill ships. The research also mentioned that most decline into the category of small and medium-sized ships, ranging from less than 500 gross tons to 25,000 gross tons. Another study which was compiled by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, the agency has forecast the acceleration of global ship breaking, notably oil tankers and container ships, from now on, but particularly from 2020 until 2023. This reflects the scrapping of ships built during the later half of the 1990s, with a useful life of 26 or 27 years. -

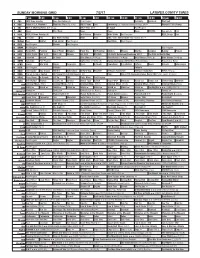

Sunday Morning Grid 7/2/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/2/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Hot Seat PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Swimming U.S. National Championships. (N) Å Women’s PGA Champ. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News XTERRA Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid 2017 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 The Path to Wealth-May 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) Duro pero seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. Recuerda y Gana 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow NOVA (TVG) Å 52 KVEA Hoy en la Copa Confed Un Nuevo Día Edición Especial (N) Copa Copa FIFA Confederaciones Rusia 2017 Chile contra Alemania. -

Forecasting with Twitter Data: an Application to Usa Tv Series Audience

L. Molteni & J. Ponce de Leon, Int. J. of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics. Vol. 11, No. 3 (2016) 220–229 FORECASTING WITH TWITTER DATA: AN APPLICATION TO USA TV SERIES AUDIENCE L. MOLTENI1 & J. PONCE DE LEON2 1Decision Sciences Department, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy. 2Target Research, Milan, Italy. ABSTRACT Various researchers and analysts highlighted the potential of Big Data, and social networks in particular, to optimize demand forecasts in managerial decision processes in different sectors. Other authors focused the attention on the potential of Twitter data in particular to predict TV ratings. In this paper, the interactions between television audience and social networks have been analysed, especially considering Twitter data. In this experiment, about 2.5 million tweets were collected, for 14 USA TV series in a nine-week period through the use of an ad hoc crawler created for this purpose. Subsequently, tweets were classified according to their sentiment (positive, negative, neutral) using an original method based on the use of decision trees. A linear regression model was then used to analyse the data. To apply linear regression, TV series have been grouped in clusters; clustering is based on the average audience for the individual series and their coefficient of variability. The conclusions show and explain the existence of a significant relationship between audience and tweets. Keywords: Audience, Forecasting, Regression, Sentiment, TV, Twitter. 1 INTRODUCTION Many authors in these years highlighted the potential of Big Data in general to support better quantitative forecasting approaches to economic data. In particular, a recent and very interesting work from Hassani and Silva [1] summarized the problems and potential of Big Data forecasting. -

2020 Commencement Program

JAPANESE GREETING KOREAN GREETING ДОБРО ПОЖАЛОВАТЬ! ABUHAY M Семьям и друзьям наших Sa pamilya at mga kaibigan выпускников: ng mga magsisipagtapos: Сегодня является Ang araw na ito ay особенно важным днем natatangi para sa Colegio ng для нашего колледжа. Occidental. Sa araw na ito 134 Сегодня мы гордимся nais naming ipaabot ang женщинами и мужчинами, pag-papahalaga sa lahat ng 134 получающими их magsisipagtapos upang дипломы как глава 134- maging kabahagi ng 134 na летней истории этого taon sa kasaysayan ng ating заведения. Сегодня мы institusyon. Sa araw na ito собираемся отметить tayo’y magsama-sama upang кульминацию их трудов и ipagdiwang ang hangganan решительности, отметить ng kanilang mga pagsisikap at это важнейшее в жизни pagtitiyaga, upang itakda достижение, и пожелать itong isang makahulugang им больших успехов в bahagi ng kanilang buhay, at будущем. Мы рады, что upang ipaabot ang pagbati na Вы сегодня приехали к sana’y makamtan nila ang нам и вашим выпускникам. matagumpay na kinabukasan. Они находят величайшее Kaming lahat, kasama ng удовольствие в том, что mga magsisipagtapos ay Вы гордитесь их nasisiyahan sa inyong pagdalo достижениями. Они sa araw na ito. Ikalulugod знают, что сегодня они nilang matanggap ang inyong исполнились ващи pagpuri sa kanilang mga надежды. nakamtang tagumpay. Sa Мы собираемся как araw na ito ng pagtatapos Оксидентельская семья batid nilang naisakatuparan отметить этот важный nila ang iyong mga pangarap день в жизни наших at gayon din ang sa kanila. студентов и желать им Tayo’y magsama-sama успехов в будущем. Если bilang isang pamilya ng Вы сегодня посещаете Occidental upang ipagdiwang наш кампус первый раз, itong pinakamahalagang или Вы часто посещали bahagi ng buhay ng ating нас, мы радостно mga mag-aaral at naisin ang принимаем Вас. -

50 SIGN on BONUS AFTER 30 DAYS! Call the Circulation Dept

PAGE 8B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, JUNE 12, 2015 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JUNE 15, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- Tina’s Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase A Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Vintage St. Louis” Painting by Frank Fight for legal status. Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å Ageless “Vintage St. Louis” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ new film. Report (N) Å Zappa; violin. (N) Å Show News Kitchen KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent 2015 Stanley Cup Final: Game 6 -- Lightning at Blackhawks News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly Extra (N) Paid Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big 2015 Stanley Cup Final Game 6 -- Tampa Bay Lightning at Chicago KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Blackhawks. If necessary. If game is not necessary, “American Ninja News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Warrior” and “The Island” will air. (N) Å (N) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE CLOSER AND SAVING GRACE: FEMINIST AND GENRE THEORY IN 21ST CENTURY TELEVISION Lelia M. Stone, B.A., M.P.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Albert Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Art Goven, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stone, Lelia M. A Textual Analysis of The Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21st Century Television. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2013, 89 pp., references 82 titles. Television is a universally popular medium that offers a myriad of choices to viewers around the world. American programs both reflect and influence the culture of the times. Two dramatic series, The Closer and Saving Grace, were presented on the same cable network and shared genre and design. Both featured female police detectives and demonstrated an acute awareness of postmodern feminism. The Closer was very successful, yet Saving Grace, was cancelled midway through the third season. A close study of plot lines and character development in the shows will elucidate their fundamental differences that serve to explain their widely disparate reception by the viewing public. Copyright 2013 by Lelia M. Stone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters Page 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

2021-06-20-Losangeles.Pdf

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/20/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Feel the Beat (N) Å We Need to Talk (N) LPGA Tour Golf Meijer LPGA Classic, Final Round. 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. (N) 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Grow Hair 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. News ABC7 Game NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest StaySexy Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Spot On Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse Skin Care Neck Pain NeuroQ Chef Emeril’s Secret 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs Paid Prog. Mercy Neck Pain News The Issue 1 8 KSCI SmileMO Dental SmileMO AAA Paid Prog. Emeril Relief SmileMO Bathroom? NeuroQ Prostate WalkFit! 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Marias Project Fire Simply Ming Milk Street How She 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Rick Steves Great Performances (TVG) Å Dream 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Naturaleza Naturaleza Paws, Bones and Rock ’n’ Roll (2015, Comedia) (N) Al punto con Jorge 4 0 KTBN R. -

Archaeology at Ras Muari: Sonari, a Bronze Age Fisher-Gatherers Settlement at the Hab River Mouth (Karachi, Pakistan)

The Antiquaries Journal, , ,pp– © The Society of Antiquaries of London, . This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./S First published online August ARCHAEOLOGY AT RAS MUARI: SONARI, A BRONZE AGE FISHER-GATHERERS SETTLEMENT AT THE HAB RIVER MOUTH (KARACHI, PAKISTAN) Paolo Biagi, Hon FSA, Renato Nisbet, Michela Spataro and Elisabetta Starnini Paolo Biagi, Department of Asian and North African Studies (DSAAM), Ca’ Foscari University, Ca’ Cappello, San Polo 2035, I-30125 Venice, Italy. Email: [email protected] Renato Nisbet, Department of Asian and North African Studies (DSAAM), Ca’ Foscari University, Ca’ Cappello, San Polo 2035, I-30125 Venice, Italy. Email: [email protected] Michela Spataro, Department of Scientific Research, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, UK. Email: [email protected] Elisabetta Starnini, Department of Civilizations and Forms of Knowledge, Pisa University, Via dei Mille 19, I-56126 Pisa, Italy. Email: [email protected] This paper describes the results of the surveys carried out along Ras Muari (Cape Monze, Karachi, Sindh) by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Lower Sindh and Las Bela in and . The surveyed area coincides with part of the mythical land of the Ichthyophagoi, mentioned by the classical chroniclers. Many archaeological sites, mainly scatters and spots of fragmented marine and mangrove shells, were discovered and AMS dated along the northern part of the cape facing the Hab River mouth. The surveys have shown that fisher and shell gatherer com- munities temporarily settled in different parts of the headland. -

Community and for Trade Unions in Gadani Ship Breaking

GADANI SHIP BREAKING WORKERS STRUGGLE NATIONAL TRADE UNION FEDERATION (NTUF) GADANI Gadani is a coastal village of Lasbela District of Province of Balochistan located about 43 km south-west of Karachi. The present estimated population of this village is 35000. 97% of the population is Muslim with a small Hindu minority. Belong to Sanghur, Kurd, Sajdi, Muhammad Hasni, and Bezinjo tribes. Majority of the population speaks Balochi with some Sindhi Majority of the people are illiterate. Majority of the people are living beyond poverty line. 10 coal power plants of total capacity of 6,600 MW with technical and financial assistance of China is under consideration. GADANI SHIP BREAKING YARD Ship Breaking at Gadani introduced in the year 1973. Gadani was the world's largest ship-breaking site in the 1980s, where oil tankers and bulk carriers were taken there to be dismantled. Presently third largest ship breaking yard in the world. The total area of the Ship Breaking yards spread over 12 KM. 132 Ship-Breaking Yards/Plots Each yard/plot consisting of 8 acres One acre is equal to 4840 square yard One meter is equal to 1.094 yards. Each yard/plot consisting of 4840x8=38720 yards or 38720x 1.094= 42359.68 meters Presently 34 companies are working as Ship-Breaking Companies. In the 2009-2010 fiscal year, a record 107 ships, with a combined light displacement tonnage (LDT) of 852,022 tons, were broken. It currently has an annual capacity of breaking up to 135 ships of all sizes, including super tankers, with a combined LDT of 1,400,000