A Simple Wedding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May-June 1975

AY/JUNE 1975 $100 ABORTION: PAST AND P DAISY DEBOLT )LLYWOOD'S FILMS ABOUT MEN OUR PRISONS FOR WOMEN CONTENTS IP IN EVERY ISSUE letters 2 Editor here and there 4 Sharon Batt editorial Barbara Hartmann 5 Art music: Daisy Debolt Beverley Ross 6 Barbara Hartmann, Director Art perspectives Mary-Lynn Burke 30 Linda Donnelly film Brigitte Kerwer 34 lona MacAllister Susan Bordo 36 Audrey Watson Layout people in this issue 44 Marianne English Naomi Loeb FEATURES Diane Walton Photography Alice Baumann-Rondez Abortion: Diana Selsor Palling Woman's Body, Man's Law Kingston Women's Centre 9 Business Mary Alyce Heaton Female Prisoners MaryEllen Gillan 16 Fiction Karen Lawrence, Editor Susan McMaster WOMEN IN THE ARTS Helen Rosta Carol Rink Diane Walton Livelihood from Pots Eunice Willar 13 Demonstration Rosalind MacPhee 14 Nonfictkwi Sharon Batt, Editor Prayer Marylu Antonelli Mary Alyce Heaton On this street Naomi Loeb The Seedling 15 Public Relations Series 2 Fantasy Anna Hook 21 Marylu Antonelli Leola Smith Naomi Loeb Ginny Stikeman Resource Planning Susan McMaster, Director Un Cri Lointain Erika Wanke 20 Sharon Batt He said Beth Jankola 28 Karen Lawrence Naomi Loeb Kitty Got a Postcard Administrative Debra Holt Poesie Erika Wanke 38 Branching Out is published every two months by the New Women's Magazine Society, Edmonton, Alberta. Please send cover photo by Alice Baumann-Rondez all correspondence to Box 4098, Edmon ton, Alberta T6E4T1. Submissions should be typed, double-spaced and ac companied by a stamped, self- addressed envelope. Advertising rates are available on request. Copyright 1975 by The New Women's Magazine Society, Edmonton. -

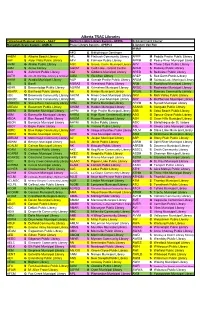

Alberta TRAC Libraries

Alberta TRAC Libraries Yellowhead Regional Library - ASGY Northern Lights Library System - AEPNL G Government Courier Marigold Library System - ASMLS Peace Library System - APRPLS S System Van Run M Mail AFD G Bibliothèque Dentinger AABM S Alberta Beach Library AFL M Flatbush Community Library APPP M Paddle Prairie Public Library AAF S Alder Flats Public Library AFV G Fairview Public Library APRM G Peace River Municipal Library AAIM G Airdrie Public Library AGC G Grande Cache Municipal Library APV S Three Cities Public Library AAM S Acme Library AGCM G Cold Lake - Grand Centre ARAD S Radway Public Library AAS S Ashmont Public Library AGI S Gibbons Municipal Library ARED S Redwater Public Library AATH G Alice B. Donahue Library & Archives AGM S Gleichen Library AREP S Red Earth Public Library AAVA S Acadia Municipal Library AGP G Grande Prairie Public Library ARLM M Rainbow Lake Municipal Library AB S Banff AGRAS S Grassland Public Library ARM S Rockyford Municipal Library ABAR S Beaverlodge Public Library AGWM G Grimshaw Municipal Library AROC S Rochester Municipal Library ABARR G Barrhead Public Library AH G Hinton Municipal Library ARUM S Rumsey Community Library ABC M Brownvale Community Library AHCM S Hines Creek Municipal Library ARV S Rich Valley Public Library ABCBC M Bear Point Community Library AHL G High Level Municipal Library ARY S McPherson Municipal Library ABDSRC S Sheep River Community Library AHM G Hanna Municipal Library ARYM S Rycroft Municipal Library ABEAM S Beaumont Public Library AHOM S Holden Municipal Library ASANS S Sangudo Public Library ABEM S Beiseker Municipal Library AHPM G High Prairie Municipal Library ASB S Seba Beach Public Library ABM G Bonnyville Municipal Library AHRM G High River Centennial Library ASG G Spruce Grove Public Library ABOA S Bon Accord Public Library AHUM S Hussar Municipal Library ASH G Swan Hills Municipal Library ABON S Bonanza Municipal Library AHYM S Hythe Public Library ASIC S Bibliothèque de St. -

Directory of Seniors' Centres in Alberta

DIRECTORY OF SENIORS’ CENTRES IN ALBERTA Directory of Seniors’ Centres in Alberta If you have any questions or require additional information, please call the Alberta Supports Contact Centre toll-free at 1-877-644-9992 or 780-644-9992 in Edmonton Directory Criteria Seniors’ centres included in the directory have met certain criteria. The centres must be not-for-profit and offer at least one on-going service or activity designed for seniors. Only those centres that submitted a completed questionnaire were considered for inclusion in the directory. Keeping Information Current The information contained in this document is subject to change. New seniors’ centres emerge and others move or disband. Updates will continue to be made to the website version of the directory at www.health.alberta.ca. To request a copy or to offer updates, please contact Alberta Health by mail, telephone or fax: Alberta Health Strategic Planning and Policy Development Division Policy Development and Community Partnerships Box 3100 Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4W3 Fax: (780) 422-8762 Telephone: Alberta Supports Contact Centre Toll-free: 1-877-644-9992 Edmonton and Area: (780) 644-9992 Acknowledgements Thank you to all the organizations that took the time to provide their information. Note The seniors’ centre street address is provided when available; however the postal code reflects the mailing address. Please contact the centre for complete mailing address if required. i © 2014 Government of Alberta Categories Used Services and programs described in the directory are listed in categories. The centre must offer at least one related service for the category to be listed. -

2019 Land Ownership

120°12'0"W 120°10'0"W 120°8'0"W 120°6'0"W 120°4'0"W 120°2'0"W 120°0'0"W 119°58'0"W 119°56'0"W 119°54'0"W 119°52'0"W 119°50'0"W 119°48'0"W 119°46'0"W 119°44'0"W 119°42'0"W 119°40'0"W 119°38'0"W 119°36'0"W 119°34'0"W 119°32'0"W 119°30'0"W 119°28'0"W 119°26'0"W 119°24'0"W 119°22'0"W 119°20'0"W 119°18'0"W 119°16'0"W 119°14'0"W 119°12'0"W 119°10'0"W 119°8'0"W 119°6'0"W 119°4'0"W 119°2'0"W 119°0'0"W 118°58'0"W 118°56'0"W 118°54'0"W 118°52'0"W 118°50'0"W 118°48'0"W 118°46'0"W 118°44'0"W 118°42'0"W 118°40'0"W 118°38'0"W 118°36'0"W 118°34'0"W 118°32'0"W 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 3 3 3 1 0 2 2 2 2 0 2 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 9 9 0 0 9 9 9 8 0 8 8 8 8 7 7 7 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 5 5 5 5 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 N 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 2 1 0 9 " 8 7 6 5 E E E E E E E E E 0 E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E D D D E E E E E ' D D D D D E E E E N D D D D E E E E D D D D E E D D D D 1 D D D D G G G G D D D D D 1 G G G G G D D D D D 1 G G G G D D D G G G G D D D D G G G G D D D R R R 1 G G G G " R R R R R G G G G R R R R G G G G G R R R R G G G G R R R R G G G G 4 R R R R G G R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R 0 R R 2 ' E E ° E E E E 4 E E E D D D D D 6 D D D G D 2 G G G G G G R G R G R R 5 R ° R R R R R R R R R R R R R 6 5 M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W 3 2 2 1 1 0 0 9 9 8 8 7 7 6 6 5 5 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 E E E E E E E E E E E E E E -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

Global and Regional Maps NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd

NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Wilson Ridge Receipt Meter Station Attachment 6 Global and Regional Maps NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Attachment 6 Wilson Ridge Receipt Meter Station Global and Regional Maps Northwest Territories Alberta FORT MCMURRAY GRANDE PRAIRIE Saskatchewan WILSON RIDGE RECEIPT M/S EDMONTON British Columbia CALGARY MEDICINE HAT TERMS OF USE: The datasets used to create this map have been gathered from various sources for a specific purpose. TransCanada Corp. provides no warranty regarding the accuracy or completeness of the datasets. Unauthorized or improper use of this map, including supporting datasets is strictly prohibited. TransCanada Corp. accepts no liability whatsoever related to any loss or damages resulting from proper, improper, authorized or unauthorized use of this map and associated datasets and user expressly waives all claims relating to or arising out of use of or reliance on this map. Receipt Meter Station WILSON RIDGE RECEIPT METER STATION Existing NGTL Pipeline LOCATION: REVISION: ISSUED DATE: City / Town SE-24-68-07-W6M 0 17-10-31 Global COORDINATE SYSTEM: ISSUE PURPOSE: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 11N IFU CARTOGRAPHER: RB 17-10-31 0 25 50 100 150 200 250 km REVIEWER: EG 17-10-31 FILE NAME: APPROVER: EG 17-10-31 T_0125_001_WilsonRidge_Receipt_MS_.mxd April 2018 Page 1 of 3 NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Attachment 6 Wilson Ridge Receipt Meter Station Global and Regional Maps 731 49 SILVERWOOD BIRCH HILLS BRIDGEVIEWSILVERWOOD 77 COUNTY BRIDGEVIEW 744 SADDLE PEORIA NORTHMARK 677 PEORIA 679 HILLS NORTHMARK WOKING WOKING 76 M. D. OF COUNTY GUY 2 733 SMOKY RIVER 75 HOMESTEAD HOMESTEAD NO. -

Calgary Public Library, Saddletown Branch

ALBERTA PUBLIC LIBRARY DIRECTORY JULY, 2016 On the Cover: Calgary Public Library, Saddletown Branch INTRODUCTION The Alberta Public Library Directory is produced annually by Alberta Municipal Affairs, Public Library Services Branch. At the time of printing, there are 7 library system boards and 222 municipal and intermunicipal library boards. Together they operate 322 public library service points in the province of Alberta. Library System Board. Established by Minister through agreement between two or more municipalities and/or school authorities as provided for under Section 13 of the Libraries Act, Statutes of Alberta Ch. L-11. A system is supported by local taxes and is governed by a board consisting of one member appointed by each participant, and additional members appointed in accordance with the Libraries Regulation. Municipal Library Board. Established by passage of a bylaw under Section 3 of the Libraries Act, Statutes of Alberta Ch. L-11. The library is supported by municipal taxes and is governed by a board of not less than five and not more than ten members, all appointed by the council of the municipality. Not more than two members of council may be appointed as members of the Board. Intermunicipal Library Board. Established by Minister under Section 12 of the Libraries Act when up to 3 municipalities pass laws and enter into an agreement to create an intermunicipal board. The next update of this directory is planned for July, 2017. Please notify the Public Library Services Branch of any related changes. Phone Toll Free: -

Grande Prairie

26 12 17 22 25 32 3 7 16 24 27 33 6 11 16 23 30 33 2 8 15 14 19 20 26 34 5 15 24 29 34 1 9 13 21 25 35 4 3 14 19 28 35 6 10 18 22 30 36 2 10 13 36 5 11 17 23 29 31 32 1 11 18 20 27 31 4 12 16 24 28 27 33 6 12 17 21 26 32 76-7-W6 3 7 15 19 26 76-26-W5 34 5 7 75-11-W6 22 25 33 76-8-W6 2 76-6-W6 8 14 76-3-W6 20 25 76-25-W5 35 77-24-W5 4 3 8 16 23 30 75-9-W6 34 1 9 76-4-W6 13 21 29 36 2 9 15 24 29 35 6 10 18 22 23 28 27 31 32 77-23-W5 14 19 28 75-8-W6 36 5 11 17 26 33 75-14-W6 10 13 20 27 31 4 76-5-W6 12 16 24 19 25 34 11 Albright Lake 18 21 26 32 3 7 15 20 30 35 2 12 17 22 25 33 2 8 14 21 29 36 7 16 23 30 34 1 9 13 22 28 31 32 1 75-13-W6 8 15 24 29 35 6 10 18 17 23 27 33 6 9 14 19 28 5 11 16 24 26 34 5 10 13 20 27 36 4 12 15 20 21 25 30 35 4 26 31 3 7 14 22 29 3 11 18 21 25 32 2 8 13 23 28 32 12 17 22 30 33 1 9 18 24 27 L 2 23 34 10 i 75-12-W6 7 16 29 6 17 19 26 t 1 8 15 24 35 5 11 76-2-W6 20 25 t 34 28 16 l 35 Keeping Lake 6 9 14 19 27 36 4 12 15 21 30 29 e 5 10 13 20 31 3 7 14 22 28 36 4 11 18 21 26 25 32 2 8 9 13 23 24 S 27 31 3 75-10-W6 22 75-7-W6 33 1 10 17 16 19 mok 26 32 DEMMITT 12 17 23 30 75-6-W6 34 6 11 76-1-W6 15 20 y 33 2 7 16 24 29 35 5 12 14 21 R 29 1 8 15 28 36 4 i 34 14 19 27 3 7 13 22 v 28 35 6 9 20 31 8 18 23 e 27 36 5 10 13 21 26 32 2 9 17 24 r 26 4 11 18 22 25 33 1 6 10 16 19 20 25 31 3 12 17 23 30 34 11 15 76-24-W5 21 30 43 32 2 7 16 24 29 35 5 4 12 14 13 22 74-14-W6 £¤ 33 1 8 15 19 28 36 3 8 9 18 23 19 29 34 6 9 14 20 27 31 32 2 10 17 28 35 10 13 21 26 1 11 16 20 27 36 5 11 18 22 25 33 34 6 12 15 21 26 31 4 17 30 35 -

SUMMARY of the PUBLIC BOARD MEETING – October 14, 2011

SUMMARY OF THE PUBLIC BOARD MEETING – October 14, 2011 The Alberta Health Services (“AHS”) Board met on October 14, 2011 at the Northern Lights Health Region Corporate Offices in Fort McMurray. The following is an account of the resolutions approved at the meeting. A Summary is released following each Board meeting and posted on the AHS website. The meeting can also be viewed in its entirety from a link at www.albertahealthservices.ca. If you have any questions regarding this information, please contact the Board Office at [email protected]. ITEMS OF DISCUSSION 1. Approval of Land Sale to City of Edmonton – University of Alberta Hospital, North LRT Extension 2. Approval of Land Sale to City of Edmonton – Glenrose – Norwood Road Widening 3. Health Advisory Council – Appointment of Chair 4. Health Advisory Council Member Appointments 1. Approval of Land Sale to City of Edmonton – University of Alberta Hospital, North LRT Extension The City of Edmonton requested that Alberta Health Services sell a strip of land adjacent to the current Light Rail Transit or LRT right of way at the University of Alberta Hospital, along 114th Street. The additional right of way is required by the City to establish a south terminal of the new North LRT line. The parcel is 9 metres wide, for a total land sale of 0.39 acres. The parcel is valued at $1.01 million, as per two independent appraisals. The Alberta Health Services Board: (a) approved the sale of the 0.39 acre strip of land situated along the eastern boundary of the property located at the University of Alberta Hospital site along 114th Street in Edmonton and legally described as “Parcel Q, Plan 882 1049”, from AHS to the City of Edmonton for consideration of $1.01 million, subject to receipt of approval from the Minister of Health and Wellness; and (b) authorized and directed management of AHS to request that the Minister of Health and Wellness approve this land sale. -

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

Supplement of High-Resolution Meteorological Forcing Data for Hydrological Modelling and Climate Change Impact Analysis in the Mackenzie River Basin

Supplement of Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 629–645, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-629-2020-supplement © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of High-resolution meteorological forcing data for hydrological modelling and climate change impact analysis in the Mackenzie River Basin Zilefac Elvis Asong et al. Correspondence to: Zilefac Elvis Asong ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. Table S1: List of observation stations located over the Mackenzie River Basin. The start and end dates for data availability as well the percentage of missing data during the period 2005 – 2016 for climate variables are indicated. The climate variables are P=Precipitation; T=Air Temperature; RH=Relative Humidity; wind=Wind Speed; and ps=Surface Pressure. Coordinates Record % Complete Station Name Prov. ID Lat Long Elev. Start End T P RH ps wind TULITA A NT 1650 64.91 -125.57 100.30 1903 2014 32.9 44.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 CAMPSIE AB 2490 54.13 -114.68 670.60 1910 2013 72.3 72.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 BEAVERLODGE CDA AB 2658 55.20 -119.40 744.90 1913 2007 5.1 4.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 ENTRANCE AB 2511 53.37 -117.70 990.60 1917 2006 6.2 11.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 FORT RESOLUTION A NT 1654 61.18 -113.69 160.30 1930 2014 34.3 42.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 FORT NELSON A BC 1455 58.84 -122.60 381.90 1937 2012 65.5 65.5 63.9 64.2 64.4 WATSON LAKE A YT 1615 60.12 -128.82 687.35 1938 2014 81.9 81.9 80.0 82.5 82.5 CARROT CREEK LO AB 2492 53.45 -115.87 1043.90 1939 2011 11.3