Loudness and Dynamic Range in Broadcast Audio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model HR-ADC1 Analog to Digital Audio Converter

HALF-RACK SERIES Model HR-ADC1 Analog to Digital Audio Converter • Broadcast Quality Analog to Digital Audio Conversion • Peak Metering with Selectable Hold or Peak Store Modes • Inputs: Balanced and Unbalanced Stereo Audio • Operation Up to 24 bits, 192 kHz • Output: AES/EBU, Coaxial S/PDIF, AES-3ID • Selectable Internally Generated Sample Rate and Bit Depth • External Sync Inputs: AES/EBU, Coaxial S/PDIF, AES-3ID • Front-Panel External Sync Enable Selector and Indicator • Adjustable Audio Input Gain Trim • Sample Rate, Bit Depth, External Sync Lock Indicators • Peak or Average Ballistic Metering with Selectable 0 dB Reference • Transformer Isolated AES/EBU Output The HR-ADC1 is an RDL HALF-RACK product, featuring an all metal chassis and the advanced circuitry for which RDL products are known. HALF-RACKs may be operated free-standing using the included feet or may be conveniently rack mounted using available rack-mount adapters. APPLICATION: The HR-ADC1 is a broadcast quality A/D converter that provides exceptional audio accuracy and clarity with any audio source or style. Superior analog performance fine tuned through audiophile listening practices produces very low distortion (0.0006%), exceedingly low noise (-135 dB) and remarkably flat frequency response (+/- 0.05 dB). This performance is coupled with unparalleled metering flexibility and programmability with average mastering level monitoring and peak value storage. With external sync capability plus front-panel settings up to 24 bits and up to 192 kHz sample rate, the HR-ADC1 is the single instrument needed for A/D conversion in demanding applications. The HR-ADC1 accepts balanced +4 dBu or unbalanced -10 dBV stereo audio through rear-panel XLR or RCA jacks or through a detachable terminal block. -

Audio Engineering Society Convention Paper

Audio Engineering Society Convention Paper Presented at the 128th Convention 2010 May 22–25 London, UK The papers at this Convention have been selected on the basis of a submitted abstract and extended precis that have been peer reviewed by at least two qualified anonymous reviewers. This convention paper has been reproduced from the author's advance manuscript, without editing, corrections, or consideration by the Review Board. The AES takes no responsibility for the contents. Additional papers may be obtained by sending request and remittance to Audio Engineering Society, 60 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10165-2520, USA; also see www.aes.org. All rights reserved. Reproduction of this paper, or any portion thereof, is not permitted without direct permission from the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. Loudness Normalization In The Age Of Portable Media Players Martin Wolters1, Harald Mundt1, and Jeffrey Riedmiller2 1 Dolby Germany GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany [email protected], [email protected] 2 Dolby Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT In recent years, the increasing popularity of portable media devices among consumers has created new and unique audio challenges for content creators, distributors as well as device manufacturers. Many of the latest devices are capable of supporting a broad range of content types and media formats including those often associated with high quality (wider dynamic-range) experiences such as HDTV, Blu-ray or DVD. However, portable media devices are generally challenged in terms of maintaining consistent loudness and intelligibility across varying media and content types on either their internal speaker(s) and/or headphone outputs. -

Dolby Cineasset User Manual 005058 Issue 6

Dolby CineAsset User’s Manual 22 July 2019 CAS.OM.005058.DRM Issue 6 Notices Notices Copyright © 2019 Dolby Laboratories. All rights reserved. Dolby Laboratories, Inc. 1275 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94103-1410 USA Telephone 415-558-0200 Fax 415-645-4000 http://www.dolby.com Trademarks Dolby and the double-D symbol are registered trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. The following are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories: Dialogue Intelligence™ Dolby Theatre® Dolby® Dolby Vision™ Dolby Advanced Audio™ Dolby Voice® Dolby Atmos® Feel Every Dimension™ Dolby Audio™ Feel Every Dimension in Dolby™ Dolby Cinema™ Feel Every Dimension in Dolby Atmos™ Dolby Digital Plus™ MLP Lossless™ Dolby Digital Plus Advanced Audio™ Pro Logic® Dolby Digital Plus Home Theater™ Surround EX™ Dolby Home Theater® All other trademarks remain the property of their respective owners. Patents THIS PRODUCT MAY BE PROTECTED BY PATENTS AND PENDING PATENT APPLICATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES AND ELSEWHERE. FOR MORE INFORMATION, INCLUDING A SPECIFIC LIST OF PATENTS PROTECTING THIS PRODUCT, PLEASE VISIT http://www.dolby.com/patents. Third-party software attributions Portions of this software are copyright © 2012 The FreeType Project (freetype.org). All rights reserved. Dolby CineAsset software is based in part on the work of the Qwt project (qwt.sf.net). This software uses libraries from the FFmpeg project under the LGPLv2.1. This product includes software developed by the OpenSSL Project for use in the OpenSSL Toolkit (openssl.org). This product includes cryptographic software -

Psychoacoustics Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Editor-In-Chief for Audiology Brad A

PSYCHOACOUSTICS Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Editor-in-Chief for Audiology Brad A. Stach, PhD PSYCHOACOUSTICS Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Jennifer J. Lentz, PhD 5521 Ruffin Road San Diego, CA 92123 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pluralpublishing.com Copyright © 2020 by Plural Publishing, Inc. Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Garamond by Flanagan’s Publishing Services, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by McNaughton & Gunn, Inc. All rights, including that of translation, reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems without the prior written consent of the publisher. For permission to use material from this text, contact us by Telephone: (866) 758-7251 Fax: (888) 758-7255 e-mail: [email protected] Every attempt has been made to contact the copyright holders for material originally printed in another source. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will gladly make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lentz, Jennifer J., author. Title: Psychoacoustics : perception of normal and impaired hearing with audiology applications / Jennifer J. Lentz. Description: San Diego, CA : Plural Publishing, -

Rockbox User Manual

The Rockbox Manual for Sansa Fuze+ rockbox.org October 1, 2013 2 Rockbox http://www.rockbox.org/ Open Source Jukebox Firmware Rockbox and this manual is the collaborative effort of the Rockbox team and its contributors. See the appendix for a complete list of contributors. c 2003-2013 The Rockbox Team and its contributors, c 2004 Christi Alice Scarborough, c 2003 José Maria Garcia-Valdecasas Bernal & Peter Schlenker. Version unknown-131001. Built using pdfLATEX. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sec- tions, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. The Rockbox manual (version unknown-131001) Sansa Fuze+ Contents 3 Contents 1. Introduction 11 1.1. Welcome..................................... 11 1.2. Getting more help............................... 11 1.3. Naming conventions and marks........................ 12 2. Installation 13 2.1. Before Starting................................. 13 2.2. Installing Rockbox............................... 13 2.2.1. Automated Installation........................ 14 2.2.2. Manual Installation.......................... 15 2.2.3. Bootloader installation from Windows................ 16 2.2.4. Bootloader installation from Mac OS X and Linux......... 17 2.2.5. Finishing the install.......................... 17 2.2.6. Enabling Speech Support (optional)................. 17 2.3. Running Rockbox................................ 18 2.4. Updating Rockbox............................... 18 2.5. Uninstalling Rockbox............................. 18 2.5.1. Automatic Uninstallation....................... 18 2.5.2. Manual Uninstallation......................... 18 2.6. Troubleshooting................................. 18 3. Quick Start 20 3.1. -

Le Décibel ( Db ) Est Un Sous-Multiple Du Bel, Correspondant À 1 Dixième De Bel

Emploi du Décibel, unité relative ou unité absolue Le décibel ( dB ) est un sous-multiple du bel, correspondant à 1 dixième de bel. Nommé en l’honneur de l'inventeur Alexandre Graham Bell, le bel est unité de mesure logarithmique du rapport entre deux puissances, connue pour exprimer la puissance du son. Grandeur sans dimension en dehors du système international, le bel n'est pas l'unité la plus fréquente. Le décibel est plus couramment employé. Équivalent à 1/10 de bel, le décibel comme le bel, peut être utilisé dans les domaines de l’acoustique, de la physique, de l’électronique et est largement répandue dans l’ensemble des champs de l’ingénierie (fiabilité, inférence bayésienne, etc.). Cette unité est particulièrement pertinente dans les domaines où la perception humaine est mise en jeu, car la loi de Weber-Fechner stipule que la sensation ressentie varie comme le logarithme de l’excitation. où S est la sensation perçue, I l'intensité de la stimulation et k une constante. Histoire des bels et décibels Le bel (symbole B) est utilisé dans les télécommunications, l’électronique, l’acoustique ainsi que les mathématiques. Inventé par des ingénieurs des Laboratoires Bell pour mesurer l’atténuation du signal audio sur une distance d’un mile (1,6 km), longueur standard d’un câble de téléphone, il était appelé unité de « transmission » à l’origine, ou TU (Transmission unit ), mais fut renommé en 1923 ou 1924 en l’honneur du fondateur du laboratoire et pionnier des télécoms, Alexander Graham Bell . Définition, usage en unité relative Si on appelle X le rapport de deux puissances P1 et P0, la valeur de X en bel (B) s’écrit : On peut également exprimer X dans un sous multiple du bel, le décibel (dB) un décibel étant égal à un dixième de bel.: Si le rapport entre les deux puissances est de : 102 = 100, cela correspond à 2 bels ou 20 dB. -

Dvdit Pro Tutorial

TUTORIAL SONIC ™ DVDit® Pro 6 POWERFUL DVD AUTHORING FOR VIDEO PROFESSIONALS FROM SONIC THE HOLLYWOOD STANDARD IN DVD CREATION © Copyright 2005 Sonic Solutions. All rights reserved. DVDit Pro Tutorial — Sonic Part Number 800207 Rev B (09/05) This manual, as well as the software described in it, is furnished under license and may only be used or copied in accordance with the terms of such license. The information in this manual is furnished for informational use only, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by Sonic Solutions. Sonic Solutions assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in this book. Except as permitted by such license, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Sonic Solutions. SONIC SOLUTIONS, INC. (“SONIC”) MAKES NO WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, REGARDING THE SOFTWARE. SONIC DOES NOT WARRANT, GUARANTEE, OR MAKE ANY REPRESENTATIONS REGARDING THE USE OR THE RESULTS OF THE USE OF THE SONIC SOFTWARE IN TERMS OF ITS CORRECTNESS, ACCURACY, RELIABILITY, CURRENTNESS, OR OTHERWISE. THE ENTIRE RISK AS TO THE RESULTS AND PERFORMANCE OF THE SONIC SOFTWARE IS ASSUMED BY YOU. THE EXCLUSION OF IMPLIED WARRANTIES IS NOT PERMITTED BY SOME STATES. THE ABOVE EXCLUSION MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU. IN NO EVENT WILL SONIC, ITS DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, EMPLOYEES, OR AGENTS BY LIABLE TO YOU FOR ANY CONSEQUENTIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR INDIRECT DAMAGES (INCLUDING DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF BUSINESS PROFITS, BUSINESS INTERRUPTION, LOSS OF BUSINESS INFORMATION, AND THE LIKE) ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE SOFTWARE EVEN IF SONIC HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Loudness Standards in Broadcasting. Case Study of EBU R-128 Implementation at SWR

Loudness standards in broadcasting. Case study of EBU R-128 implementation at SWR Carbonell Tena, Damià Curs 2015-2016 Director: Enric Giné Guix GRAU EN ENGINYERIA DE SISTEMES AUDIOVISUALS Treball de Fi de Grau Loudness standards in broadcasting. Case study of EBU R-128 implementation at SWR Damià Carbonell Tena TREBALL FI DE GRAU ENGINYERIA DE SISTEMES AUDIOVISUALS ESCOLA SUPERIOR POLITÈCNICA UPF 2016 DIRECTOR DEL TREBALL ENRIC GINÉ GUIX Dedication Für die Familie Schaupp. Mit euch fühle ich mich wie zuhause und ich weiß dass ich eine zweite Familie in Deutschland für immer haben werde. Ohne euch würde diese Arbeit nicht möglich gewesen sein. Vielen Dank! iv Thanks I would like to thank the SWR for being so comprehensive with me and for letting me have this wonderful experience with them. Also for all the help, experience and time given to me. Thanks to all the engineers and technicians in the house, Jürgen Schwarz, Armin Büchele, Reiner Liebrecht, Katrin Koners, Oliver Seiler, Frauke von Mueller- Rick, Patrick Kirsammer, Christian Eickhoff, Detlef Büttner, Andreas Lemke, Klaus Nowacki and Jochen Reß that helped and advised me and a special thanks to Manfred Schwegler who was always ready to help me and to Dieter Gehrlicher for his comprehension. Also to my teacher and adviser Enric Giné for his patience and dedication and to the team of the Secretaria ESUP that answered all the questions asked during the process. Of course to my Catalan and German families for the moral (and economical) support and to Ema Madeira for all the corrections, revisions and love given during my stay far from home. -

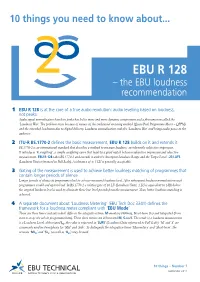

EBU R 128 – the EBU Loudness Recommendation

10 things you need to know about... EBU R 128 – the EBU loudness recommendation 1 EBU R 128 is at the core of a true audio revolution: audio levelling based on loudness, not peaks Audio signal normalisation based on peaks has led to more and more dynamic compression and a phenomenon called the ‘Loudness War’. The problem arose because of misuse of the traditional metering method (Quasi Peak Programme Meter – QPPM) and the extended headroom due to digital delivery. Loudness normalisation ends the ‘Loudness War’ and brings audio peace to the audience. 2 ITU-R BS.1770-2 defines the basic measurement, EBU R 128 builds on it and extends it BS.1770-2 is an international standard that describes a method to measure loudness, an inherently subjective impression. It introduces ‘K-weighting’, a simple weighting curve that leads to a good match between subjective impression and objective measurement. EBU R 128 takes BS.1770-2 and extends it with the descriptor Loudness Range and the Target Level: -23 LUFS (Loudness Units referenced to Full Scale). A tolerance of ± 1 LU is generally acceptable. 3 Gating of the measurement is used to achieve better loudness matching of programmes that contain longer periods of silence Longer periods of silence in programmes lead to a lower measured loudness level. After subsequent loudness normalisation such programmes would end up too loud. In BS.1770-2 a relative gate of 10 LU (Loudness Units; 1 LU is equivalent to 1dB) below the ungated loudness level is used to eliminate these low level periods from the measurement. -

Optimizing the Implementation of Dolby Digital Plus in Soc Designs

White Paper Optimizing the Implementation of Dolby Digital Plus in SoC Designs Chris Cavigioli and Brett Miller, MIPS Technologies Roger Dressler and Rob Hislop, Dolby Laboratories January 2007 MIPS Technologies and Dolby Laboratories have collaborated to provide a rapid and low-risk methodology for deploying Dolby Digital Plus technology to the set-top box and HD DVD/Blu-ray Disc markets. Introduction Dolby® Digital Plus, the newest generation of Dolby Digital, the standard-setting audio technology from Dolby Laboratories, is making its way into next-generation home entertainment applications, bringing superior sound quality, more efficient audio compression, and an improved user experience to the home. Dolby Digital Plus, also known as Enhanced AC-3 (E-AC-3), was developed to address the changing requirements of two burgeoning consumer markets. For the emerging HD DVD and Blu-ray Disc optical disc players, the data compression capabilities of Dolby Digital Plus allow movie studios to combine a superior audio experience with high-definition video. The technology also enhances the latest digital TV set-top boxes (STBs), enabling broadcasters to deploy offerings with lower bit rates, reducing costs and adding flexibility and value for consumers. While there are tremendous advantages to using Dolby Digital Plus, there are also design considerations that system-on-a-chip (SoC) teams need to understand. The rigorous approval testing that is required at Dolby Laboratories before a chip or a system can use the Dolby Digital Plus logo is substantial. Working with Dolby Laboratories, MIPS Technologies has developed an optimized, tested version of Dolby Digital Plus that will run on any of its 32-bit synthesizable processor cores—significantly slashing audio subsystem development time. -

Frequently Asked Questions Dolby Digital Plus

Frequently Asked Questions Dolby® Digital Plus redefines the home theater surround experience for new formats like high-definition video discs. What is Dolby Digital Plus? Dolby® Digital Plus is Dolby’s new-generation multichannel audio technology developed to enhance the premium experience of high-definition media. Built on industry-standard Dolby Digital technology, Dolby Digital Plus as implemented in Blu-ray Disc™ features more channels, less compression, and higher data rates for a warmer, richer, more compelling audio experience than you get from standard-definition DVDs. What other applications are there for Dolby Digital Plus? The advanced spectral coding efficiencies of Dolby Digital Plus enable content producers to deliver high-resolution multichannel soundtracks at lower bit rates than with Dolby Digital. This makes it ideal for emerging bandwidth-critical applications including cable, IPTV, IP streaming, and satellite (DBS) and terrestrial broadcast. Dolby Digital Plus is also a preferred medium for delivering BonusView (Profile 1.1) and BD-Live™ (Profile 2.0) interactive audio content on Blu-ray Disc. Delivering higher quality and more channels at higher bit rates, plus greater efficiency at lower bit rates, Dolby Digital Plus has the flexibility to fulfill the needs of new content delivery formats for years to come. Is Dolby Digital Plus content backward-compatible? Because Dolby Digital Plus is built on core Dolby Digital technologies, content that is encoded with Dolby Digital Plus is fully compatible with the millions of existing home theaters and playback systems worldwide equipped for Dolby Digital playback. Dolby Digital Plus soundtracks are easily converted to a 640 kbps Dolby Digital signal without decoding and reencoding, for output via S/PDIF. -

10700990.Pdf

The Dolby era: Sound in Hollywood cinema 1970-1995. SERGI, Gianluca. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University jj Learning and IT Services j O U x r- U u II I Adsetts Centre City Campus j Sheffield Hallam 1 Sheffield si-iwe Author: ‘3£fsC j> / j Title: ^ D o ltiu £ r a ' o UJTvd 4 c\ ^ £5ori CuCN^YTNCa IQ IO - Degree: p p / D - Year: Q^OO2- Copyright Declaration I recognise that the copyright in this thesis belongs to the author. I undertake not to publish either the whole or any part of it, or make a copy of the whole or any substantial part of it, without the consent of the author. I also undertake not to quote or make use of any information from this thesis without making acknowledgement to the author. Readers consulting this thesis are required to sign their name below to show they recognise the copyright declaration. They are also required to give their permanent address and date.