Northern Rocky Mountain Grotto Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caving Humbles the Soul. Underground I Find Myself Doing Things That Are Unimaginable Topside,” Says Mark S

“Caving humbles the soul. Underground I find myself doing things that are unimaginable topside,” says Mark S. Cosslett, adventurer and photographer. 26 163/2003 Mark S. Cosslett Photographer/Adventurer IntoAdventure Canmore, Alberta Canada Reaching Uncharted Caves with the Aid of Accurate Carbon Dioxide Measurement What started as a faint vision nearly five years ago became a reality for our team of three cavers from Canmore, Alberta last January. The karst landscape of Northwest- ern Thailand holds vast treasures of uncharted cave passages, many of which, howev- er, are guarded by high concentrations of carbon dioxide. It was the nemesis of my previous expedition back in ’98 to explore new cave passages: our team invariably got turned around by carbon dioxide. After a lot of research into bad air in caves, we set out to Thailand better equipped this time, carrying lightweight oxygen bottles and a Vaisala CARBOCAP® Hand-Held Carbon Dioxide Meter GM70. arbon dioxide (CO2) is a made us turn back, happy to deadly gas in high con- reach the surface alive. C centrations, which dis- places oxygen and results in rap- If you get into bad air, id asphyxiation. When entering you turn around uncharted passages, high carbon Upon returning home from our dioxide concentrations are one ’98 expedition, all I could think of the risks that cavers face, since about was what was around that an elevated CO2 level can also next corner in the depths of impair one’s judgment. Howev- Thailand. Within 24 hours of er, reliable methods to measure getting off the plane, I was at the CO2 on cave expeditions have library researching carbon diox- been scarce. -

Appendix 4-K Preliminary Assessment of Open Pit Slope Instability Due to the Mitchell Block Cave

APPENDIX 4-K PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF OPEN PIT SLOPE INSTABILITY DUE TO THE MITCHELL BLOCK CAVE TM SEABRIDGE GOLD INC. KSM PRELIMINARY FEASIBILITY STUDY UPDATE PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF OPEN PIT SLOPE INSTABILITY DUE TO THE MITCHELL BLOCK CAVE FINAL PROJECT NO: 0638-013-31 DISTRIBUTION: DATE: December 24, 2012 SEABRIDGE: 2 copies DOCUMENT NO: KSM12-26 BGC: 2 copies R.2.7.6 #500-1045 Howe Street Vancouver, B.C. Canada V6Z 2A9 Tel: 604.684.5900 Fax: 604.684.5909 December 24, 2012 Project No: 0638-013-31 Mr. T. Jim Smolik, Pre-Feasibility Study Manager Seabridge Gold Inc. 108 Front Street East Toronto, Ontario, M5A 1E1 Dear Mr. Smolik, Re: Preliminary Assessment of Open Pit Slope Instability due to the Mitchell Block Cave – FINAL Please find attached the above referenced report. Thank you for the opportunity to work on this interesting project. Should you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to contact the undersigned. Yours sincerely, BGC ENGINEERING INC. per: Derek Kinakin, M.Sc., P.Geo. (BC) Senior Engineering Geologist Seabridge Gold Inc., KSM Preliminary Feasibility Study Update December 24, 2012 Preliminary Assessment of Open Pit Slope Instability due to the Mitchell Block Cave FINAL Project No: 0638-013-31 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Mitchell Zone is the largest of the four exploration targets comprising Seabridge Gold Inc.’s KSM Project and is the only zone where a combination of open pit and block caving mining methods is proposed. The open pit will be mined with ultimate north and south wall heights reaching approximately 1,200 m. -

Adm Issue 10 Finnished

4x4x4x4 Four times a year Four times the copy Four times the quality Four times the dive experience Advanced Diver Magazine might just be a quarterly magazine, printing four issues a year. Still, compared to all other U.S. monthly dive maga- zines, Advanced Diver provides four times the copy, four times the quality and four times the dive experience. The staff and contribu- tors at ADM are all about diving, diving more than should be legally allowed. We are constantly out in the field "doing it," exploring, photographing and gathering the latest information about what we love to do. In this issue, you might notice that ADM is once again expanding by 16 pages to bring you, our readers, even more information and contin- ued high-quality photography. Our goal is to be the best dive magazine in the history of diving! I think we are on the right track. Tell us what you think and read about what others have to say in the new "letters to bubba" section found on page 17. Curt Bowen Publisher Issue 10 • • Pg 3 Advanced Diver Magazine, Inc. © 2001, All Rights Reserved Editor & Publisher Curt Bowen General Manager Linda Bowen Staff Writers / Photographers Jeff Barris • Jon Bojar Brett Hemphill • Tom Isgar Leroy McNeal • Bill Mercadante John Rawlings • Jim Rozzi Deco-Modeling Dr. Bruce Wienke Text Editor Heidi Spencer Assistants Rusty Farst • Tim O’Leary • David Rhea Jason Richards • Joe Rojas • Wes Skiles Contributors (alphabetical listing) Mike Ball•Philip Beckner•Vern Benke Dan Block•Bart Bjorkman•Jack & Karen Bowen Steve Cantu•Rich & Doris Chupak•Bob Halstead Jitka Hyniova•Steve Keene•Dan Malone Tim Morgan•Jeff Parnell•Duncan Price Jakub Rehacek•Adam Rose•Carl Saieva Susan Sharples•Charley Tulip•David Walker Guy Wittig•Mark Zurl Advanced Diver Magazine is published quarterly in Bradenton, Florida. -

Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas Jon T. Ehrhart Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds Part of the Geology Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Speleology Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Ehrhart, Jon T., "Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 66. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This thesis is available at SFA ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/66 Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas By Jon Ehrhart, B.S. Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Stephen F. Austin State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science STEPHEN F. -

Cave Diving in the Northern Pennines

CAVE DIVING IN THE NORTHERN PENNINES By M.A.MELVIN Reprinted from – The proceedings of the British Speleological Association – No.4. 1966 BRITISH SPELEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION SETTLE, YORKS. CAVE DIVING IN THE NORTHERN PENNINES By Mick Melvin In this paper I have endeavoured to trace the history and development of cave diving in the Northern Pennines. My prime object has been to convey to the reader a reasonable understanding of the motives of the cave diver and a concise account of the work done in this particular area. It frequently occurs that the exploration of a cave is terminated by reason of the cave passage becoming submerged below water (A sump) and in many cases the sink or resurgence for the water will be found to be some distance away, and in some instances a considerable difference in levels will be present. Fine examples of this occurrence can be found in the Goyden Pot, Nidd Head's drainage system in Nidderdale, and again in the Alum Pot - Turn Dub, drainage in Ribblesdale. It was these postulated cave systems and the success of his dives in Swildons Hole, Somerset, that first brought Graham Balcombe to the large resurgence of Keld Head in Kingsdale in 1944. In a series of dives carried out between August 1944 and June 1945, Balcombe penetrated this rising for a distance of over 200 ft. and during the course of the dive entered at one point a completely waterbound chamber containing some stalactites about 5' long, but with no way on above water level. It is interesting to note that in these early cave dives in Yorkshire the diver carried a 4' probe to which was attached a line reel, a compass, and his lamp which was of the miners' type, and attached to the end of the probe was a tassle of white tape which was intended for use as a current detector. -

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 58 NUMBER 9-10 September - October 2018 AFFILIATE ORGANIZATIONS: CHOUTEAU-KCAG-LEG-LOG-MMV-MSM-MVG-OHG-PEG-RBX- SPG-SEMO-MCKC-CCC-CAIRN

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 58 NUMBER 9-10 September - October 2018 AFFILIATE ORGANIZATIONS: CHOUTEAU-KCAG-LEG-LOG-MMV-MSM-MVG-OHG-PEG-RBX- SPG-SEMO-MCKC-CCC-CAIRN. Distributed free on the MSS website: http://www.mospeleo,org/ Subscription rate for paper copies is $10.00 per year. Send check or money order made out to the Missouri Speleological Survey to the Editor, Gary Zumwalt, 1681 State Route D, Lohman, MO 65053. Telephone: 573-782-3560. Missouri Speleological Survey President's Message October 2018. Despite the foreboding forecast of biblical rains, the Fall MSS meeting at Current River State Park was a great time. Before the weekend began, we had a long list of objectives and a sizable group of cavers expected to come, as well as ambitious plans for a large map and gear display for the public. Weathermen across the region however, conspired to keep people home with predictions of heavy rain throughout the weekend and flash flood warnings across the state. As the weekend drew nearer, the number of cavers bowing out increased by the day. Nevertheless, while it did rain all day Friday and poured on us during the drive down Friday night, the rest of the weekend was fairly dry and beautiful. The Current didn't rise, so one small group monitored caves via kayak and a much larger group went to Echo Bluff State Park to work on graffiti removal, left over the Camp Zoe events, as well as to perform a bio survey, per request of the park, to see whether the cave closure had any noticeable impact on the presence of cave life. -

The Mss Liaison

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 59 NUMBER 3-4 March - April 2019 AFFILIATE ORGANIZATIONS: CAIRN – CCC – CHOUTEAU – DAEDALUS – KCAG – LEG – LOG – MCKC – MMV – MSM – MVG – OHG – PEG – RBX – SEMO – SPG. Distributed free on the MSS website: http://www.mospeleo,org/ Subscription rate for paper copies is $10.00 per year. Send check or money order made out to the Missouri Speleological Survey to the Editor, Gary Zumwalt, 1681 State Route D, Lohman, MO 65053. Telephone: 573-782-3560. Missouri Speleological Survey - President's Message - April 2019 by Dan Lamping. Our spring board meeting is quickly approaching on the weekend of May 3-5, 2019 at the Ozark Underground Laboratory (OUL) in Protem, MO within Taney County. The focus of the weekend won't be the board meeting itself, but rather to kick-off a resurvey effort of Tumbling Creek Cave to make a complete, up-to-modern-standards map for use within a GIS platform. Tumbling Creek is a roughly two mile long cave and home to a rare cave snail. The idea for the project was initiated by OUL owner Tom Aley and then further encouraged by Scott House. This will be an open project of the MSS, so those willing to actively help in the survey are welcome to attend. No experience is needed to participate, but an interest in learning is a must. If you have question about the cave trip please contact me at [email protected] Other caving opportunities will be available within the nearby Mark Twain National Forest for those who want to do their own thing. -

Guy Stover Pit Cave Clean Up

IKC UPDATE No 103 PAGE 2 DECEMBER 2011 INDIANA KARST CONSERVANCY, INC PO Box 2401, Indianapolis, IN 46206-2401 ikc.caves.org Affiliated with the National Speleological Society The Indiana Karst Conservancy is a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation and preservation of caves and karst features in Indiana and other areas of the world. The Conservancy encourages research and promotes education related to karst and its proper, environmentally compatible use. EXECUTIVE BOARD COMMITTEES / CHAIRPERSON GROTTOS & LIAISONS President Education/Outreach Bloomington Indiana Grotto* Dave Everton Jerry Lewis (2012) Don Ingle (812) 824-4380 (812) 967-7592 (see E-Board list) [email protected] Central Indiana Grotto* Web Technologies Keith Dunlap Secretary Bruce Bowman (317) 882-5420 James Adams (2012) (see E-Board list) (317) 518-8410 Dayton Underground Grotto Mike Hood [email protected] IKC Update Editor/Publisher (937) 252-2978 Keith Dunlap Treasurer (see E-Board list) Eastern Indiana Grotto Keith Dunlap (2012) Brian Leavell (317) 882-5420 Hoosier National Forest (765) 552-7619 [email protected] Jerry Lewis Evansville Metro Grotto* (see E-board list) Ernie Payne Directors (812) 477-7043 Bruce Bowman (2014) Buddha Property Manager (317) 539-2753 George Cesnik Harrison-Crawford Grotto [email protected] (812) 339-2143 Dave Black [email protected] (812) 951-3886 Dave Haun (2012) (317) 517-0795 Near Normal Grotto* Orangeville Rise Property Manager Ralph Sawyer [email protected] Steve Lockwood (309) 822-0109 (see E-board list) Don -

National Speleologi'c-Al Society

Bulletin Number Five NATIONAL SPELEOLOGI'C-AL SOCIETY n this Issue: CAVES IN WORLD HISTORY . B ~ BERT MORGAN THE GEM OF CAVES' . .. .. • B DALE WHITE CA VE FAUN A, with Recent Additions to the Lit ture Bl J. A. FOWLER CAT ALOG OF THE SOCIETY LJBR R . B)' ROBERT S. BRAY OCTOBER, 1943 PRJ E 1.0 0 . ------------------------------------------- .-'~ BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Issue Number Five October, 1943 750 Copies. 64 Pages Published sporadically by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 510 Scar Building, Washington, D. c., ac $1.00 per copy. Copyrighc, 1943, by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. EDITOR: DON BLOCH 5606 Sonoma Road, Bethesda-14, Maryland ASSOCIATE EDITORS: ROBERT BRAY WILLIAM J. STEPHENSON J. S. PETRIE OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN *WM. ]. STEPHENSON J. S. PETR'IE *LEROY FOOTE F. DURR President Vice·Prcsidet1l & Secretary Treasurer Pina~iaJ Sect'eIM"J 7108 Prospect Avenue 400 S. Glebe Road R. D. 3 2005 Kansas Avenue Richmond, Va. Arlin-glon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Richmond, Va. Archeology Fauna Hydrology Programs &. Activities FLOYD BARLOGA JAMES FOWLER DR. WM. M. MCGILL DR. JAMES BENN 202·8 Lee Boulevard 6420 14th Street 6 Wayside Place, University U. S. Nat. Museum Arlington, Va. Washington, D . C. Charlottesville, Va. Washington, D. C. Bibliography &. Library Finance Mapping PubliCity *ROBERT BRAY *l.EROY FOOTB GBORGE CRABB *·Lou KLBWEJ.t R. F. D. 2 R. F. D. 3 P. O. Box 791 Toledo Blade Herndon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Blacksburg, Va. Toledo, Ohio BuIletin &. Publications Folklore Metnbership DON BLOCH "'CLAY PERRY SAM ALLBN RECORDS 5606 Sonoma Road East Acres 1226 Wel.Jesley Avenue *FLORENCE WHITLI!Y Deorhesda, Md. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

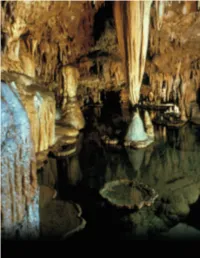

Caving “Mystery, Adventure, Discovery, Beauty, Conservation, Danger

33104-24.jo_iw_jo 12/11/03 1:28 PM Page 392 33104-24.jo_iw_jo 12/11/03 1:28 PM Page 393 24 Caving “Mystery, adventure, discovery, beauty, conservation, danger. To many who are avid cavers and speleologists, caves are all of these things and many more, too.” —David R. McClurg (caver, subterranean photographer, caving skills instructor, and longtime member of the National Speleological Society), The Amateur’s Guide to Caves and Caving, 1973 Beneath the Earth’s surface lies a magnificent realm darker than a moonless night. No rain falls. No storms rage. The seasons never change. Other than the ripple of hidden streams and the occasional splash of dripping water, this underground world is silent, yet it is not without life. Bats fly with sure reckoning through mazes of tunnels, and eyeless creatures scurry about. Transparent fish stir the waters of underground streams, and the darkness is home to tiny organisms seldom seen in broad daylight. This is the world of the cave, as beautiful, alien, and remote as the glaciated crests of lofty mountains. Just as climbers are tempted by summits that rise far above familiar ground, cavers are drawn into a subterranean wilderness every bit as exciting and remarkable as any place warmed by the rays of the sun. Water is the most common force involved in the creation of caves. As it seeps through the earth, moisture can dissolve limestone, gypsum, and other sedimentary rock. Surf pounding rocky cliffs can, over the centuries, carve out sea caves of spectacular shape and dimension. The surface of lava flowing from a volcanic eruption can cool and harden while molten rock runs out below it, leaving behind lava tubes. -

The Mss Liaison

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 60 NUMBER 9-10 September-October 2020 AFFILIATE ORGANIZATIONS: CAIRN – CCC – CHOUTEAU – DAEDALUS – KCAG – LEG – LOG – MCKC – MMV – MSM – MVG – OHG – PEG – RBX – SEMO – SPG. Distributed free on the MSS website: http://www.mospeleo,org/ Subscription rate for paper copies is $10.00 per year. Send check or money order made out to the Missouri Speleological Survey to the Editor, Gary Zumwalt, 1681 State Route D, Lohman, MO 65053. Telephone: 573-782-3560. Missouri Speleological Survey- President's Message November 2020 by Dan Lamping I'd like to share a graphic that Shelly Colatskie put together with MSS data provided by Ken Grush. It shows that 72% of the documented caves in Missouri are privately owned. Yet the data we have on the 23% of caves owned by state and federal agencies, far outnumbers that which we have on privately owned caves, which accounts for nearly 3/4 of the known caves in the state. This is a major area of potential improvement for us as an organization, to expand upon the knowledge and information we have on privately owned caves in the state since there are over 5,400 of them. We have the data to build off of and the means of sharing it with capable cavers, interested in knocking on doors and hitting the hillsides, hollows and sinkhole planes with GPS in hand. But we need those willing people, who will follow through with expanding upon the data by writing descriptions, directions, reports, etc. and sharing it back with the MSS to catalog.