Arrhythmias in Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WPW: WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE Syndrome

WPW: WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE Syndrome What is Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome? Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, or WPW, is named for three physicians who described a syndrome in 1930 in young people with episodes of heart racing and an abnormal pattern on their electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Over the next few decades, it was discovered that this ECG pattern and the heart racing was due to an extra electrical pathway in the heart. Thus, WPW is a syndrome associated with an abnormal heart rhythm, or “arrhythmia”. Most people with WPW do not have any other problems with their heart. Normally, the electrical impulses in the heart originate in the atria or top chambers of the heart and spread across the atria. The electrical impulses are then conducted to the ventricles (the pumping/bottom chambers of the heart) through a group of specialized cells called the atrioventricular node or AV node. This is usually the only electrical pathway between the atria and ventricles. In WPW, there is an additional pathway made up of a few extra cells left over from when the heart formed. The conduction of electricity through the heart causes the contractions which are the “heartbeat”. What is WPW Syndrome as opposed to a WPW ECG? A person has WPW Syndrome if they experience symptoms from abnormal conduction through the heart by the WPW pathway. Most commonly, the symptom is heart racing, or “palpitations”. The particular type of arrhythmia in WPW is called “supraventricular tachycardia” or SVT. “Tachycardia” means fast heart rate; “supraventricular” means the arrhythmia requires the cells above the ventricles to be part of the abnormal circuit. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: the Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features

diagnostics Review Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features Anna Giulia Pavon 1,2,*, Pierre Monney 1,2,3 and Juerg Schwitter 1,2,3 1 Cardiac MR Center (CRMC), Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (J.S.) 2 Cardiovascular Department, Division of Cardiology, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Faculty of Biology and Medicine, University of Lausanne (UniL), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-775-566-983 Abstract: Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) was first described in the 1960s, and it is usually a benign condition. However, a subtype of patients are known to have a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, the so called “arrhythmic MVP.” In recent years, several studies have been published to identify the most important clinical features to distinguish the benign form from the potentially lethal one in order to personalize patient’s treatment and follow-up. In this review, we specifically focused on red flags for increased arrhythmic risk to whom the cardiologist must be aware of while performing a cardiovascular imaging evaluation in patients with MVP. Keywords: mitral valve prolapse; arrhythmias; cardiovascular magnetic resonance Citation: Pavon, A.G.; Monney, P.; Schwitter, J. Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality 1. Mitral Valve and Arrhythmias: A Long Story Short Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features. In the recent years, the scientific community has begun to pay increasing attention Diagnostics 2021, 11, 683. -

Basic Arrhythmia Review Guide-Advanced

BASIC ARRHYTHMIA REVIEW GUIDE ADVANCED The following study guide provides a review of information covered in the basic arrhythmia competency. Preparation with this guide will help to achieve success on the exam. Sample questions and websites are provided at the end of this guide. DESCRIPTION OF THE HEART The adult heart is a muscular organ weighing less than a pound and about the size of a clenched fist. It lies between the right and Left left lung in an area called the mediastinal cavity behind the sternum of the breast bone. Approximately two-thirds of the heart Atrium lies to the left of the sternum and one-third to the right of the sternum. Right HEART MUSCLES Atrium The heart is composed of three layers each with its own special function. The outermost layer is called the pericardium, essentially a sac around the heart. The middle and thickest layer of the heart is called the Left myocardium. This layer contains all the atrial and ventricular Ventricle muscle fibers needed for contraction as well as the blood supply Right and electrical conduction system. Ventricle The innermost layer of the heart is the endocardium and is composed of endothelium and connective tissue. Any disruption or injury to this endothelium can lead to infection, which in turn can cause valve damage, sepsis, or death. CHAMBERS A normal human heart contains four separate chambers: right atrium, left atrium, right ventricle, and left ventricle. The right and left sides of the heart are divided by a septum. The right atrium (RA) receives oxygen-poor (venous) blood from the body’s organs via the superior and inferior vena cava (SVC and IVC). -

Tachycardia (Fast Heart Rate)

Tachycardia (fast heart rate) Working together to improve the diagnosis, treatment and quality of life for all those aff ected by arrhythmias www.heartrhythmalliance.org Registered Charity No. 1107496 Glossary Atrium Top chambers of the heart that receive Contents blood from the body and from the lungs. The right atrium is where the heart’s natural pacemaker (sino The normal electrical atrial node) can be found system of the heart Arrhythmia An abnormal heart rhythm What are arrhythmias? Bradycardia A slow heart rate, normally less than 60 beats per minute How do I know what arrhythmia I have? Cardiac Arrest the abrupt loss of heart function, breathing and consciousness Types of arrhythmia Cardioversion a procedure used to return an abnormal What treatments are heartbeat to a normal rhythm available to me? Defi brillation a treatment for life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. A defibrillator delivers a dose of electric current to the heart Important information This booklet is intended for use by people who wish to understand more about Tachycardia. The information within this booklet comes from research and previous patients’ experiences. The booklet off ers an explanation of Tachycardia and how it is treated. This booklet should be used in addition to the information given to you by doctors, nurses and physiologists. If you have any questions about any of the information given in this booklet, please ask your nurse, doctor or cardiac physiologist. 2 Heart attack A medical emergency in which the blood supply to the heart is blocked, causing serious damage or even death of heart muscle Tachycardia Fast heart rate, more than 100 beats per minute Ventricles The two lower chambers of the heart. -

The Example of Short QT Syndrome Jules C

Hancox et al. Journal of Congenital Cardiology (2019) 3:3 Journal of https://doi.org/10.1186/s40949-019-0024-7 Congenital Cardiology REVIEW Open Access Learning from studying very rare cardiac conditions: the example of short QT syndrome Jules C. Hancox1,4* , Dominic G. Whittaker2,3, Henggui Zhang4 and Alan G. Stuart5,6 Abstract Background: Some congenital heart conditions are very rare. In a climate of limited resources, a viewpoint could be advanced that identifying diagnostic criteria for such conditions and, through empiricism, effective treatments should suffice and that extensive mechanistic research is unnecessary. Taking the rare but dangerous short QT syndrome (SQTS) as an example, this article makes the case for the imperative to study such rare conditions, highlighting that this yields substantial and sometimes unanticipated benefits. Genetic forms of SQTS are rare, but the condition may be under-diagnosed and carries a risk of sudden death. Genotyping of SQTS patients has led to identification of clear ion channel/transporter culprits in < 30% of cases, highlighting a role for as yet unidentified modulators of repolarization. For example, recent exome sequencing in SQTS has identified SLC4A3 as a novel modifier of ventricular repolarization. The need to distinguish “healthy” from “unhealthy” short QT intervals has led to a search for additional markers of arrhythmia risk. Some overlap may exist between SQTS, Brugada Syndrome, early repolarization and sinus bradycardia. Genotype-phenotype studies have led to identification of arrhythmia substrates and both realistic and theoretical pharmacological approaches for particular forms of SQTS. In turn this has increased understanding of underlying cardiac ion channels. -

Heart and Circulatory System?Arrhythmia (Irregular

Heart and Circulatory System?Arrhythmia (Irregular Heartbeat) Cardiac arrhythmias have a wide range of clinical significance, depending upon the type, location of origin, symptoms present, and the likelihood for sudden or subtle incapacitation. Arrhythmias that originate in the upper chambers of the heart, the atria, are referred to as "supraventricular" arrhythmias. The atria are the heart's pacemakers and also act as primers for the pump chambers, the ventricles. The most common atrial arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation, which is a rapid, irregular rhythm that can result in dizziness, shortness of breath, or loss of consciousness if the heart rate is too slow or fast. Ventricular arrhythmias affect the lower pump chambers, the ventricles. Common ventricular arrhythmias include premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). These are fairly common in healthy people and can be brought on by a number of stimuli, including excessive caffeine consumption or stress. Ventricular tachycardia is a rapid heart rate with sudden onset. Symptoms of ventricular tachycardia include lightheadedness, fainting, weakness, or mental confusion. This type of arrhythmia is often associated with underlying heart disease and requires good medical management. The FAA issues medical certificates for many types of arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or ventricular/supraventricular arrhythmias that are not associated with underlying ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy (a disease of the heart muscle), or significant heart valve defect or outflow tract obstructions may be favorably considered for issuance of any class of medical certificate. Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs) If there is a history of PVCs occurring at a rate of more than six per minute on a resting electrocardiogram, or that have caused symptoms, the FAA will require a cardiovascular evaluation, including a 24hour Holter monitor and graded exercise treadmill test. -

Cardiac Arrhythmias Following Pneumonectomy

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.24.5.568 on 1 September 1969. Downloaded from Thorax (1969), 24, 568. Cardiac arrhythmias following pneumonectomy J0RGEN STOUGARD From the Departmenzt of Thoracic Surgery, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denlmark A series of 260 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for cancer of the lung was analysed for post-operative arrhythmias. Of these patients 28% developed such arrhythmias, usually in the form of atrial fibrillation, on the first to third post-operative day, rapidly yielding to fast-acting digitalis preparations. Possible aetiological factors were investigated, but no single cause was demonstrable. The indication for pre-operative digitalization, if any, is discussed. Arrhythmias are fairly common following mias to be as a rule atrial, occurring a few days thoracic surgery. Numerous analyses on patients after the operation, and transient. The electro- with diseases of the lung have shown that the cardiographic changes consisted mainly in the incidence increases with the extent of the pro- various forms of arrhythmia; but persistent cedure, from 5% after lobectomy to about 30% changes have also been reported. Oka, Raunio, after pneumonectomy (Cohen and Pastor, 1957; and Savola (1962) observed, following resection Mowry and Reynolds, 1964). Aetiological theories of the lung for tuberculosis, changes that indi- are many and not always equally well founded. cated hypertrophy of the right heart. Killing and Among the more plausible and well substantiated Becker (1957) have also demonstrated changes -

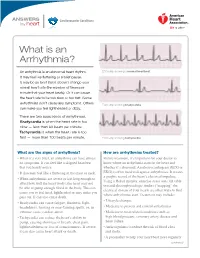

What Is an Arrhythmia?

ANSWERS Cardiovascular Conditions by heart What is an Arrhythmia? An arrhythmia is an abnormal heart rhythm. ECG strip showing a normal heartbeat It may feel like fluttering or a brief pause. It may be so brief that it doesn’t change your overall heart rate (the number of times per minute that your heart beats). Or it can cause the heart rate to be too slow or too fast. Some arrhythmias don’t cause any symptoms. Others ECG strip showing bradycardia can make you feel lightheaded or dizzy. There are two basic kinds of arrhythmias. Bradycardia is when the heart rate is too slow — less than 60 beats per minute. Tachycardia is when the heart rate is too fast — more than 100 beats per minute. ECG strip showing tachycardia What are the signs of arrhythmia? How are arrhythmias treated? • When it’s very brief, an arrhythmia can have almost Before treatment, it’s important for your doctor to no symptoms. It can feel like a skipped heartbeat know where an arrhythmia starts in the heart and that you barely notice. whether it’s abnormal. An electrocardiogram (ECG or • It also may feel like a fluttering in the chest or neck. EKG) is often used to diagnose arrhythmias. It creates a graphic record of the heart’s electrical impulses. • When arrhythmias are severe or last long enough to Using a Holter monitor, exercise stress tests, tilt table affect how well the heart works, the heart may not test and electrophysiologic studies (“mapping” the be able to pump enough blood to the body. -

The Short QT Syndrome

The Short QT Syndrome A note from the SADS Foundation References We provide this information with the hope that informing 1. Gussak I, Brugada P, Brugada J, Wright RS, Kopecky SL, Chaitman A Guide for Patients BR, Bjerregaard P. Idiopathic short QT interval: a new clinical physicians and other health care providers, as well as the public, and Health Care will encourage early and correct diagnosis and proper therapy syndrome? Cardiology 2000;94:99 –102. for congenital short QT syndrome (SQTS), resulting in the 2. Giustetto C, Di Monte F. Wolpert C, Borggrefe M, Schimpf R, Providers reduction and ultimately elimination of sudden cardiac arrest Sbragia P, Leone G, Maury P, Anttonen O, Haissaguerre M, Gaita F. (SCA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD). Short QTsyndrome: clinical findings and diagnostic-therapeutic implications. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2440 –2447. 3. Gaita F, Giustetto C, Bianchi F, Wolptert C, Schimpf R, Riccardi R, Grossi S, Richiardi E, Borggrefe M. Short QT syndrome: a familial What do Patients and Parents Need to Know cause of sudden death. Circulation 2003;108:965–970. about SQTS? 4. Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Parpia S, et al. The Prevalence and • The warning signs and symptoms of SQTS. significance of a short QT interval in 18 825 low-risk individuals • Who to see for proper testing. including athletes. Br J Sports Med 2015;0:1-6 • How to protect their children and themselves. • How to expand their family pedigree and contact other family members who may be at risk What do Physicians need to know? • When to consider SQTS as a possible diagnosis. -

Sinus Bradycardia

British Heart Journal, I97I, 33, 742-749. Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.33.5.742 on 1 September 1971. Downloaded from Sinus bradycardia Dennis Eraut and David B. Shaw From the Cardiac Department, Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter, Devon This paper presents thefeatures of 46 patients with unexplained bradycardia. Patients were ad- mitted to the study if their resting atrial rate was below 56 a minute on two consecutive occasions. Previous electrocardiograms and the response to exercise, atropine, and isoprenaline were studied. The ages of thepatients variedfrom I3 to 88years. Only 8 had a past history ofcardiovascular disease other than bradycardia, but 36 hJd syncopal or dizzy attacks. Of the 46 patients, 35 had another arrhythmia in addition to bradycardia; at some stage, i6 had sinus arrest, i.5 hadjunc- tional rhythm, 12 had fast atrial arrhythmia, I6 had frequent extrasystoles, and 6 had atrio- ventricular block. None had the classical features of sinoatrial block. Arrhythmias were often produced by exercise, atropine, or isoprenaline. Drug treatment was rarely satisfactory, but only i patient needed a permanent pacemaker. It is suggested that the majority of the patients were suffering from a pathological form of sinus bradycardia. The aetiology remains unproven, but the most likely explanation is a loss of the inherent rhythmicity of the sinoatrial node due to a primary degenerative disease. The descriptive title of 'the lazy sinus syndrome' is suggested. copyright. Bradycardia with a slow atrial rate is usually attempt to define the clinical syndrome of regarded as an innocent condition common in bradycardia with a pathologically slow atrial certain types of well-trained athlete, but occa- rate and to clarify the nature of the arrhyth- sionally it may occur in patients with symp- mia. -

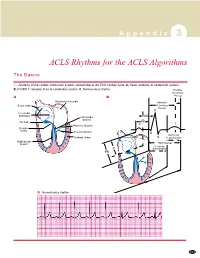

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Premature Ventricular Contractions Ralph Augostini, MD FACC FHRS

Premature Ventricular Contractions Ralph Augostini, MD FACC FHRS Orlando, Florida – October 7-9, 2011 Premature Ventricular Contractions: ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006; 48:247-346. Background PVCs are ectopic impulses originating from an area distal to the His Purkinje system Most common ventricular arrhythmia Significance of PVCs is interpreted in the context of the underlying cardiac condition Ventricular ectopy leading to ventricular tachycardia (VT), which, in turn, can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, is one of the common mechanisms for sudden cardiac death The treatment paradigm in the 1970s and 1980s was to eliminate PVCs in patients after myocardial infarction (MI). CAST and other studies demonstrated that eliminating PVCs with available anti-arrhythmic drugs increases the risk of death to patients without providing any measurable benefit Pathophysiology Three common mechanisms exist for PVCs, (1) automaticity, (2) reentry, and (3) triggered activity: Automaticity: The development of a new site of depolarization in non-nodal ventricular tissue. Reentry circuit: Reentry typically occurs when slow- conducting tissue (eg, post-infarction myocardium) is present adjacent to normal tissue. Triggered activity: Afterdepolarization can occur either during (early) or after (late) completion of repolarization. Early afterdepolarizations commonly are responsible for bradycardia associated PVCs, but also with ischemia and electrolyte disturbance. Triggered Fogoros: Electrophysiologic Testing. 3rd ed. Blackwell Scientific 1999; 158. Epidemiology Frequency The Framingham heart study (with 1-h ambulatory ECG) 1 or more PVCs per hour was 33% in men without coronary artery disease (CAD) and 32% in women without CAD Among patients with CAD, the prevalence rate of 1 or more PVCs was 58% in men and 49% in women.