Historic Environment Character Assessment: East Staffordshire August 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

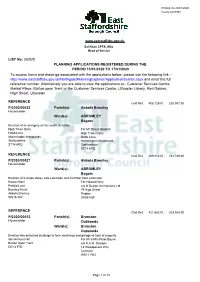

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications Below, Please Use the Following Link

Printed On 20/01/2020 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 3/2020 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 13/01/2020 TO 17/01/2020 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 408,129.00 : 328,507.00 P/2020/00023 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Householder Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Erection of an orangery on the south elevation High Trees Dairy For Mr Shaun Hodson Hobb Lane High Trees Dairy Marchington Woodlands Hobb Lane Staffordshire Marchington Woodlands ST14 8RQ Staffordshire ST14 8RQ REFERENCE Grid Ref: 409,852.00 : 323,539.00 P/2020/00027 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Householder Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Erection of a single storey side extension and first floor front extension Rowan Barn For Howard Why Pinfold Lane c/o bi Design Architecture Ltd Bromley Hurst 79 High Street Abbots Bromley Repton WS15 3AF DE65 6GF REFERENCE Grid Ref: 421,582.00 : 323,928.00 P/2020/00012 Parish(s): Branston Householder Outwoods Ward(s): Branston Outwoods Erection two detached buildings to form workshop and garage to front of property 46 Henhurst Hill For Mr & Mrs Peter Boyce Burton Upon Trent c/o R.A.M. Designs DE13 9TD 18 Woodpecker Way Cannock WS11 7WJ Page 1 of 10 Printed On 20/01/2020 Weekly List ESBC LIST No: 3/2020 REFERENCE Grid Ref: 425,817.00 : 322,674.00 P/2020/00004 Parish(s): Brizlincote Householder Ward(s): Brizlincote Erection of a first floor rear extension. -

STAFFORDSHIRE. (KELLY's

110 BUTTERTON. STAFFORDSHIRE. (KELLY's heads and other objects of.. antiquity have been found. days excepted. Postal Orders are isSIUed here & paid. A. J. Hambleton esq. and Mrs. Burnett, of Clayton Wetton is the nearest money order office; Warslow is House, are the principal landowners. There are also a the nearest telegraph office, 2 miles distant number of freeholders. The soil is clay; subsoil, clay Public Elementary School, built about 1848 & enlarged and rock. The land is nearly all pasturage. The acre- in I895, for 93 children; average attendance, 45; & age is I,499; the population of the civil and ecclesiastical endowed with a house & land left by William Melior, (St. Bartholomew) parish in I9DI was 263. now let for £I5 a year; the school is the property of Parish Clerk & Sexton, William Burnett. the trustees <Jf William Melior's charity; John Bart~ ley, master Post Office. John Salt, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive Carriers to Leek.-Ernest Frith & William Salt, on wed. from Leek at 8.25 a.m.; dispatched, 4.40 p.m.; sun- nesda.y Burnett Mrs. Clayton house Edge Richard, farmer & grocer, corn Poyser Selina (Miss), farmer, Butter- Crump Rev. Roberb John (incumbent) & provision merchant, wholesale egg ton moor Hambleton .Arthur Jn. Middleton ho & butter factor, Churchyard ~ide Salt John, shopkeeper, & post office & Wardle Sir Thomas F.G.S., F.C.S., Frith Ernest, carrier overseer J.P. Swainsley Goldstraw John (Mrs.),farmer,Moor ho Salt Joseph, farmer, Bank house Williams Mrs. Greenlow Gould John, farmer, Butterton moor Salt Joseph, Red Lion P.H Gould Thomas, farmer Salt Richard, farmer, Bollandshall Hambleton Jas. -

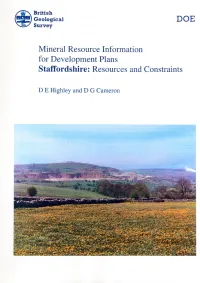

Mineral Resources Report for Staffordshire

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORT WF/95/5/ Mineral Resources Series Mineral Resource Information for Development Plans Staffordshire: Resources and Constraints D E Highley and D G Cameron Contributors: D P Piper, D J Harrison and S Holloway Planning Consultant: J F Cowley Mineral & Resource Planning Associates This report accompanies the 1:100 000 scale maps: Staffordshire Mineral resources (other than sand and gravel) and Staffordshire Sand and Gravel Resources Cover Photograph Cauldon limestone quarry at Waterhouses, 1977.(Blue Circle Industries) British Geological Survey Photographs. No. L2006. This report is prepared for the Department of the Environment. (Contract PECD7/1/443) Bibliographic Reference Highley, D E, and Cameron, D G. 1995. Mineral Resource Information for Development Plans Staffordshire: Resources and Constraints. British Geological Survey Technical Report WF/95/5/ © Crown copyright Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 1995 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey Offices Sales Desk at the Survey headquarters, Keyworth, Nottingham. The more popular maps and books may be purchased from BGS- Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG approved stockists and agents and over the counter at the 0115–936 3100 Fax 0115–936 3200 Bookshop, Gallery 37, Natural History Museum (Earth Galleries), e-mail: sales @bgs.ac.uk www.bgs.ac.uk Cromwell Road, London. Sales desks are also located at the BGS BGS Internet Shop: London Information Office, and at Murchison House, Edinburgh. www.british-geological-survey.co.uk The London Information Office maintains a reference collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Some BGS Murchison House, West Mains Road, books and reports may also be obtained from the Stationery Office Edinburgh EH9 3LA Publications Centre or from the Stationery Office bookshops and 0131–667 1000 Fax 0131–668 2683 agents. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1

Southern Staffordshire Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1 Stafford Borough, Lichfield District, Tamworth Borough, South Staffordshire District and Cannock Chase District Councils July 2010 Final Report 9V5955 CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General Overview 1 1.2 Objectives of the SWMP 1 1.3 Scope of the SWMP 3 1.3.1 Phase 1 - Preparation 5 1.3.2 Phase 2 - Risk Assessment 5 2 ESTABLISHING A PARTNERSHIP 7 2.1 Identification of Partners 7 2.2 Roles and Responsibilities 9 2.3 Engagement Plan 10 2.4 Objectives 10 3 COLLATE AND MAP INFORMATION 11 3.1 Data Collection and Quality 11 3.1.1 Historic Flood Event Data 12 3.1.2 Future Flood Risk Data 15 3.2 Mapping and GIS 18 3.2.1 Surface Water Flooding 18 3.2.2 Flood Risk Assets 19 3.2.3 SUDS Map 19 3.2.4 Summary Sheets 20 4 STAFFORD BOROUGH 23 4.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 23 4.2 Surface Water Management 24 4.3 Recommendations 25 5 LICHFIELD DISTRICT 27 5.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 27 5.2 Surface Water Management 28 5.2.1 Canal Restoration 29 5.3 Recommendations 31 6 TAMWORTH BOROUGH 33 6.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 33 6.2 Surface Water Management 34 6.3 Recommendations 35 7 SOUTH STAFFORDSHIRE DISTRICT 37 7.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 37 7.2 Surface Water Management 38 7.2.1 Canal Restoration 39 7.3 Recommendations 41 Southern Staffordshire SWMP Phase 1 9V5955/R00003/303671/Soli Final Report -i- July 2010 8 CANNOCK CHASE DISTRICT 43 8.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 43 8.2 Surface Water Management 44 8.2.1 Canal Restoration 45 8.3 Recommendations 47 9 SELECTION OF AN APPROACH FOR FURTHER ANALYSIS -

Premises Licence List

Premises Licence List PL0002 Drink Zone Plus Premises Address: 16 Market Place Licence Holder: Jasvinder CHAHAL Uttoxeter 9 Bramblewick Drive Staffordshire Littleover ST14 8HP Derby Derbyshire DE23 3YG PL0003 Capital Restaurant Premises Address: 62 Bridge Street Licence Holder: Bo QI Uttoxeter 87 Tumbler Grove Staffordshire Wolverhampton ST14 8AP West Midlands WV10 0AW PL0004 The Cross Keys Premises Address: Burton Street Licence Holder: Wendy Frances BROWN Tutbury The Cross Keys, 46 Burton Street Burton upon Trent Tutbury Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE13 9NR Staffordshire DE13 9NR PL0005 Water Bridge Premises Address: Derby Road Licence Holder: WHITBREAD GROUP PLC Uttoxeter Whitbread Court, Houghton Hall Business Staffordshire Porz Avenue ST14 5AA Dunstable Bedfordshire LU5 5XE PL0008 Kajal's Off Licence Ltd Premises Address: 79 Hunter Street Licence Holder: Rajeevan SELVARAJAH Burton upon Trent 45 Dallow Crescent Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE14 2SR Stafffordshire DE14 2PN PL0009 Manor Golf Club LTD Premises Address: Leese Hill Licence Holder: MANOR GOLF CLUB LTD Kingstone Manor Golf Club Uttoxeter Leese Hill, Kingstone Staffordshire Uttoxeter ST14 8QT Staffordshire ST14 8QT PL0010 The Post Office Premises Address: New Row Licence Holder: Sarah POWLSON Draycott-in-the-Clay The Post Office Ashbourne New Row Derbyshire Draycott In The Clay DE6 5GZ Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 5GZ 26 Jan 2021 at 15:57 Printed by LalPac Page 1 Premises Licence List PL0011 Marks and Spencer plc Premises Address: 2/6 St Modwens Walk Licence Holder: MARKS -

South Staffordshire Response Cannock Chase Council Supports

South Staffordshire response Cannock Chase Council supports the continued positive approach to meeting wider Housing Market Area needs and acknowledgment of the necessity to reconsider the levels of provision as the quantity of the shortfall is reviewed on an ongoing basis. It is noted that this stage of the consultation covers housing growth only; is strategic in nature; and that individual site are not yet being considered. However, it is understood that the preferred strategic spatial approach will inform the future selection of development sites and broad locations are identified as part of the Preferred Spatial Strategy Option G. As part of this, it is noted that paragraph 2.7 of the consultation document states ‘the distribution of housing growth proposed in this consultation may alter to reflect specific site opportunities once these are assessed in more detail.’ Cannock Chase Council would welcome continued discussions as part of the site selection process in relation to any potential cross boundary sites and sites that lie in proximity to the Cannock Chase District boundary. It is noted that as part of the indicative preferred spatial strategy there appear to limited levels of additional housing proposed (in addition to existing allocations and safeguarded land) in areas adjacent to Cannock Chase District, primarily at Huntington and Cheslyn Hay/Great Wyrley. As outlined in the Cannock Chase District Local Plan Issues and Options (May 2019) the Council is currently considering options for accommodating its own housing needs, and potentially those of the wider HMA. The document identified that after taking into account the existing urban capacity for development, and the potential capacity arising from the former Rugeley Power Station redevelopment, there would be a shortage against the District’s own housing needs alone (before consideration of wider HMA needs). -

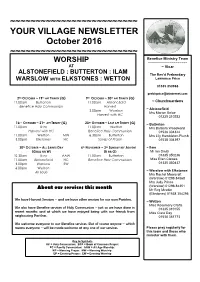

YOUR VILLAGE NEWSLETTER October 2016

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ YOUR VILLAGE NEWSLETTER October 2016 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Benefice Ministry Team WORSHIP ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ AT ~ Vicar B e ALSTONEFIELD : BUTTERTON : ILAM The Rev’d Prebendary n WARSLOW WITH ELKSTONES : WETTON Lawrence Price e 01335 350968 f i [email protected] c 2ND OCTOBER ~ 19TH AFT TRINITY (G) 9TH OCTOBER ~ 20TH AFT TRINITY (G) e 11.00am Butterton 11.00am Alstonefield ~ Churchwardens Benefice Holy Communion Harvest M ~ Alstonefield 3.00pm Warslow i Mrs Marion Beloe Harvest with HC n 01335 310253 i TH ST RD 16 OCTOBER ~ 21 AFT TRINITY (G) 23 OCTOBER ~ LAST AFT TRINITY (G) ~ Butterton s 11.00am Ilam 11.00am Wetton Mrs Barbara Woodward t Harvest with HC Benefice Holy Communion 01538 304324 r 11.00am Wetton MW 6.30pm Butterton Mrs Lily Hambleton-Plumb y 3.00pm Elkstones HC Songs of Praise 01538 304397 T 30TH OCTOBER ~ ALL SAINTS DAY 6TH NOVEMBER ~ 3RD SUNDAY BEF ADVENT ~ Ilam e (GOLD OR W) (R OR G) Mr Ian Smith a 10.30am Ilam AAW 11.00am Butterton 01335 350236 m Miss Ellen Clewes 11.00am Alstonefield HC Benefice Holy Communion ~ 01335 350437 3.00pm Warslow EW ~ 6.00pm Wetton ~ ~ Warslow with Elkstones All Souls ~ Mrs Rachel Moorcroft ~ (Warslow) 01298 84568 ~ Mrs Judy Prince ~ (Warslow) 01298 84351 ~ About our services this month Mr Reg Meakin ~ (Elkstones) 01538 304295 ~ We have Harvest Services – and we have other services for our own Parishes. ~ ~ Wetton ~ Miss Rosemary Crafts ~ We also have Benefice services of Holy Communion – just as we have done in 01335 310155 ~ recent months; and at which we have enjoyed being with our friends from Miss Clare Day ~ neighouring Parishes. -

Staffordshire 1

Entries in red - require a photograph STAFFORDSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position ST_ABCD06 SK 1077 4172 B5032 EAST STAFFORDSHIRE DENSTONE Quixhill Bank, between Quixhill & B5030 jct on the verge ST_ABCD07 SK 0966 4101 B5032 EAST STAFFORDSHIRE DENSTONE Denstone in hedge ST_ABCD09 SK 0667 4180 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALTON W of Gallows Green on the verge ST_ABCD10 SK 0541 4264 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALTON near Peakstones Inn, Alton Common by hedge ST_ABCD11 SK 0380 4266 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Threapwood in hedge ST_ABCD11a SK 0380 4266 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Threapwood in hedge behind current maker ST_ABCD12 SK 0223 4280 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Lightwood, E of Cheadle in hedge ST_ABCK10 SK 0776 3883 UC road EAST STAFFORDSHIRE CROXDEN Woottons, between Hollington & Rocester on the verge ST_ABCK11 SK 0617 3896 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHECKLEY E of Hollington in front of wood & wire fence ST_ABCK12 SK 0513 3817 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHECKLEY between Fole and Hollington in hedge Lode Lane, 100m SE of Lode House, between ST_ABLK07 SK 1411 5542 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Alstonefield and Lode Mill on grass in front of drystone wall ST_ABLK08 SK 1277 5600 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Keek road, 100m NW of The Hollows on grass in front of drystone wall ST_ABLK10 SK 1073 5832 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Leek Road, Archford Moor on the verge -

Baseline Report: Climate Change Mitigation & Adaptation Study

Baseline Report Climate Change Adaptation & Mitigation Staffordshire County Council Project number: 60625972 16 October 2020 Revision 04 Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Harper Robertson Luke Aldred Luke Aldred Matthew Turner Senior Sustainability Associate Director Associate Director Regional Director Consultant Alice Purcell Graduate Sustainability Consultant Luke Mulvey Graduate Sustainability Consultant Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 01 20 February 2020 Skeleton Report Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 02 31 March 2020 Draft for issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 03 11 September 2020 Final issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 04 16 October 2020 Updated fuel consumption Y Luke Associate and EV charging points Aldred Director Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council AECOM Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council Prepared by: Harper Robertson Senior Sustainability Consultant E: [email protected] AECOM Limited Aldgate Tower 2 Leman Street London E1 8FA United Kingdom aecom.com © 2020 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. -

8 Fountain Road Draycott in the Clay, Ashbourne, DE6 5HP

8 Fountain Road Draycott in the Clay, Ashbourne, DE6 5HP Available with no upward chain, this modern three bedroom detached bungalow with garage, occupies an appealing cul de sac position within the village of Draycott in the Clay. The bungalow features double glazing, electric heating, and stands within neat attractive gardens. Guide Price £175,000 www.JohnGerman.co.uk Distinctly Draycott in the Clay offers a range of amenities including a The Three Bedrooms all have windows overlooking the Rear primary school, general store and village inns. It is conveniently Garden and electric heaters. The Bathroom has a three piece positioned for access to the A515, A50 and A38 with links to suite with panelled bath and shower over, wash basin and w.c. Uttoxeter, Burton upon Trent and Derby. In all an ideal plus a window to the side. retirement home. Outside Accommodation The bungalow is set in a cul de sac position with a Driveway A glazed door opens into a good sized Entrance Hall with doors leading past the front lawn to the Garage with up and over door, leading to all rooms. The well proportioned Lounge has ample light and rear access door. natural light provided by two bay windows to the front and a stone finish fireplace with slate hearth provides an attractive focal The enclosed Rear Garden has gated access, paved walkways point. The Lounge also features coving, a storage heater and a and low maintenance gravelled areas with a variety of shrubs glazed door to the Hall. and trees. There is also a Garden Shed. -

Magnetic Mapping of the Butterton Dyke: an Example of Detailed Geophysical Surveying

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 144, 1987, pp. 29-33, 5 figs. Printed in Northern Ireland Magnetic mapping of the Butterton Dyke: an example of detailed geophysical surveying W.T. C. SOWERBUTTS Department of Geology, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Abstract: A detailed vertical gradient magnetic survey of part of a small intrusion known as the Butterton Dyke has been made with the aid of a microcomputer-based data gathering system. The results of over 16500 magnetic measurements made by one person in less than a day have given results which reveal a detailed pattern of magnetic anomalies. From these it is possible to trace the course of two dykes for a distance of over 300 m, and identify places where they change direction and showsmall offsets. The advantage of making vertical gradient rather than total fieldmagnetic measurements include a faster surveying speed and better resolution of near-surface anomalies. This paper describes the execution and results of a detailed seconds. One reason for making a magnetic survey of part magnetic survey made over part of a Tertiary intrusion in of the Butterton Dyke was to see if useful information could Staffordshire, England. The surveywas made in order to be obtained using another type of magnetometer, a assesspossible geological applications of a magnetic magnetic gradiometer, whenused with a microcomputer gradiometer connected to a microcomputerbased data based data gathering system. The aimwas to find out if gathering system. measurements of magnetic gradient wouldbe effective at Twodeeply weathered olivine dolerite dykes are defining the course of a shallow igneous intrusion, and if a exposed in a disused quarry at the southern end of Church more detailed survey, than isfeasible with a proton Wood, Butterton, 4 km south of Newcastle-under-Lyme, magnetometer, wouldreveal information about fine England (Grid Ref.