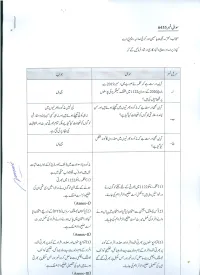

Human Rights Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Supplement 14 August 2019

Special Supplement 14 th August 2019 Afghan President Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Visit to Pakistan (June-2019) Guard of Honour to President Ashraf Ghani President Ashraf Ghani meeting with President Ashraf Ghani in Delegation Level Talks with Prime Minister at PM House, Islamabad Prime Minister Imran Khan in Islamabad (27 June, 2019) Imran Khan at Prime Minister›s House, Islamabad (June 27, 2019) Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi called on President Ashraf Ghani addresses the Business President Ashraf Ghani’s Address at the Institute President Ashraf Ghani laying floral wreath at the grave of President Ashraf Ghani in Serana Hotel, Islamabad Community at Governor House, Lahore of Strategic Studies (ISSI) Islamabad the Poet of East Dr. Allama Mohammad Iqbal in Lahore Pakistan Funded Projects in Afghanistan Allama Iqbal Faculty Block, University of Kabul Liaqat Ali Khan Faculty Sir Syed Postgraduate Faculty Rehman Baba High School, Kabul (Balkh University) Mazar-e-Sharif of Sciences Nangarhar University, Jalalabad Pakistani State Minister for Parliamentary Affairs, Ali Mohammad Khan, Vice President of Afghanistan, Mr. Shehryar Khan Afridi Minister for States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON) Pakistan along with Mohammad Sarwar Danish along with Dr. Ferozuddin Feroz, Minister for Public Health and Ambassador of Dr. Ferozuddin Feroz, Minister for Public Health and Ambassador of Pakistan Zahid Nasrullah Khan, Pakistan, Zahid Nasrullah Khan, on 20th April 2019, jointly inaugurated Mohammad Ali Jinnah Hospital in Kabul. on 24 July 2019, jointly inaugurated Nayeb Aminullah Khan Hospital in Logar Province, Afghanistan. Pak-Afghan Main Crossing Points Chaman Border Angoor Adda Crossing Point Ghulam Mohammad Khan Crossing Point Torkham Border Chief Minister KPK Mahmood Khan Visietd Turkham to see Operational Arrangements for 24/7 openning of Pak-Afghan Border The Asian Development Bank-Funded Central Asian Regional Economic Corridor (CAREC) Border Crossing Point Project at Torkham. -

December 16-31, 2019 October 01-15, 2020

December 16-31, 2019 October 01-15, 2020 SeSe 1 Table of Contents 1: October 01, 2020………………………………….……………………….…03 2: October 02, 2020………………………………….……………………….....06 3: October 03, 2020…………………………………………………………......10 4: October 04, 2020………………………………………………...…................13 5: October 05, 2020………………………………………………..…..........….. 14 6: October 06, 2020………………………………………………………….…..22 7: October 07, 2020………………………………………………………………25 8: October 08, 2020……………………………………….………………….......31 9: October 09, 2020……………………………………………...……………….35 10: October 10, 2020…………………………………………………….............39 11: October 11, 2020………………………………………………………….….42 12: October 12, 2020……………………………………………………………. 44 13: October 13, 2020…………………………………………………………..…47 14: October 14, 2020………………………………………………………..….....51 15: October 15, 2020……………………………………………….………..…... 57 Data collected and compiled by Rabeeha Safdar, Mahnoor Raza, Anosh and Muqaddas Sanaullah Disclaimer: PICS reproduce the original text, facts and figures as appear in the newspapers and is not responsible for its accuracy. 2 October 01, 2020 Daily Times China-Pakistan journey of friendship 1951 The two countries establish diplomatic relations 1955 Visit of Vice President Madam Song Ching Ling to Pakistan 1956 Visit of Prime Minister HS Suhrawardy to China 1963 Visit of Foreign Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to China 1963 Pakistan and China concludes boundary agreement 1964 PIA starts flights to Beijing, becoming the first non-communist country airline to fly from Beijing 1965 Agreement on Cultural Cooperation signed 1970 Pakistan -

Khyber Medical University, Peshawar

KHYBER MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, PESHAWAR BACHELOR OF MEDICINE & BACHELOR OF SURGERY (MBBS) FINAL PROFESSIONAL ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2013 EXAMINATION HELD IN MAY - JULY 2014 RESULT DECLARED ON AUGUST 15, 2014 MAX MARKS: 2000 NOTIFICATION NO. MBBS-FP-A13-01 Roll Registration No. Name of Candidates Father's Name Result No. Khyber Girls Medical College, Peshawar 7001 2007-KGMC-145 NOOR UL SABAH SHAH MURAD ALI SHAH Re: Med, Sur, Eye 7002 2008/KMU/KGMC/001 MEMOONA JABEEN GHULAM RABANI 1289 7003 2008/KMU/KGMC/002 MARIAM KHALID KHALID PERVAIZ 1402 7004 2008/KMU/KGMC/003 AFSHAN AWAN NAIK MUHAMMAD 1441 MUHAMMAD SAJAWAL KHAN 7005 2008/KMU/KGMC/004 FOQIA AWAN AWAN 1452 7006 2008/KMU/KGMC/005 LAILA KHAN MIR AKBAR KHAN 1359 7007 2008/KMU/KGMC/006 SHUMAILA ZEB ALAM ZEB 1476 7008 2008/KMU/KGMC/007 SABEEHA KHAN SHER ZAMIN KHAN 1318 7009 2008/KMU/KGMC/008 FARAH NAZ JALIL-UR RAHMAN 1444 7010 2008/KMU/KGMC/009 MUNAZZA AYUB MUHAMMAD AYUB KHAN 1557 7011 2008/KMU/KGMC/010 MEHREEN SALAHUDDIN DR. SALAHUDDIN 1390 7012 2008/KMU/KGMC/011 SANA ZAHID MUHAMMAD ZAHID 1450 7013 2008/KMU/KGMC/012 SHAMAMA-RAHIM RAHIM-SHAH 1374 7014 2008/KMU/KGMC/013 SADAF REHMAN SAIF-UR-REHMAN 1465 7015 2008/KMU/KGMC/014 SUNDAS SHAUKAT SHAUKAT JAVED 1325 7016 2008/KMU/KGMC/015 MINA GUL SHAHJEHAN 1332 7017 2008/KMU/KGMC/016 SHAZIA GUL AYAZ GUL 1452 7018 2008/KMU/KGMC/017 HADIA GUL MATI ULLAH 1388 7019 2008/KMU/KGMC/018 MEHAK MUKHTAR SAID MUKHTAR BACHA 1485 7020 2008/KMU/KGMC/019 SAIRA JAVED JAVED IQBAL 1379 7021 2008/KMU/KGMC/021 NIDA GUL ROZI KHAN 1316 7022 2008/KMU/KGMC/022 MARYAM MUNIR MUNIR AHMED SHAH 1511 7023 2008/KMU/KGMC/023 HOOR-ASAD ULLAH JAN ASADULLAH JAN 1350 7024 2008/KMU/KGMC/024 SADAF RASHID RASHID KHAN 1396 7025 2008/KMU/KGMC/025 SIDRA IRFAN IRFANULLAH 1294 7026 2008/KMU/KGMC/026 IRSA SHUAIB MUHAMMAD SHUAIB FULALY 1302 7027 2008/KMU/KGMC/027 FARAH GUL DR. -

KPK Assembly

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad the 5th June, 2013 No.F.2(43)/2013-Cord.- In pursuance of the provisions of sub-section (3A) and sub-section (4) of Section 42 of the Representation of the People Act, 1976 (Act No. LXXXV of 1976), the Election Commission of Pakistan hereby publishes the names of candidates returned to the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from the constituencies mentioned below against the name of each candidate: Sl. Names of the No. of Total No. Total votes Name of the No Contesting valid votes of rejected polled in the candidate Candidates secured by the votes constituency declared Constesting elected with Party Affiliation candidates 1. 2. 3. 4. 5 6 PK-1 PESHAWAR-I 1 Ajmal Khan 227 2 Ghazanfar Bilour 4782 3 M. Zakir Shah 1063 4 Irfan Ullah 72 5 Gul Jan 16 6 Mosab Mukhtar 29 7 Zia Ullah Afridi 22932 Zia Ullah Afridi (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf) 8 Muhammad Adeel 1571 9 Hassan Khan 12 10 Ashfaq Ahmad 334 11 Bahrullah Khan 5156 12 Mir Alam Khan 26 13 Zahoor Khan 21 14 Akhunzada Irfan Ullah Shah 4819 15 Muhammad Shah Zeb 252 16 Muhammad Younas 14 17 Saif Ullah 249 18 Muhammad Nadeem 178 19 Muhammad Nadeem 234 20 Muhammad Akbar Khan 4376 21 Abdur Rahim Khan 6 22 Muhammad Nadeem 6907 23 Yasar Farid 20 24 Zafar Ullah 28 25 Younas Khan 63 26 Malik Parvez Khan 55 27 Abdul Aziz Khan 198 Total 53640 811 54451 PK-2 PESHAWAR-II 1 Hidayat Ullah Khan Afridi Advocat 56 2 Sardar Naeem 305 3 Shamsur Rehman Safi 86 4 Pir Abdur Rehman 85 5 Saeed Ur Rehman Safi 2782 6 Shahid Noor 74 7 Shafqat Hussain Durrani 125 8 Siraj Ud Din 2453 9 Malik Ghulam Mustafa 6273 1 1. -

Db List for 19-05-2021(Wednesday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR WEDNESDAY, 19 MAY, 2021 MR. JUSTICE QAISER RASHID KHAN, CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE SYED ARSHAD ALI MOTION CASES 1. CM Rest 75- Jamal Khan Niaz ALi Khan Khalil P/2021(in WP No. V/s 7482/19 DG NADRA Muhammad Mubarik, Writ Petition (Dismissed by Branch AG Office HCJ,VII)) (175194) 2. COC 204- Aslam Khan & another Shoukat Khan Safi P/2021(in WP No. V/s 5078-P/2020 Federation of Pakistan & others Writ Petition Branch AG Office (Against Order HJ-IX,XI)) (174981) 3. COC 206- Farzana Bibi Muhammad Irshad (Mardan) P/2021(in WP No. V/s 2652-P/2020 Hajiz Ibrahim & others Hidayatullah (Focal Person), (Against Order Muhammad Khalid Matten, Writ Ex.Judge,XI)) Petition Branch AG Office (175032) 4. W.P 6662-P/2018() KP Law Officer Welfare Khalid Rehman (135591) Association V/s Muhammad Anwar Khan Banvi, The Governmnet of KPK Writ Petition Branch AG Office i W.P 6658/2018 KP Law Officer Welfare Khalid Rehman V/s Association Muhammad Anwar Khan Banvi, The Government of KPK Writ Petition Branch AG Office 5. W.P 6095-P/2019() Abdullah Malik Mushtaq Ahmad (151980) V/s Cantonment Board, Peshawar Deputy Attorney General, Through Exeuctive Off Muhammad Javeed Abbasi, Ihsanullah IT Branch Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 53 Video Link only available in Court # 1,2,3 and 4 _ 2 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR WEDNESDAY, 19 MAY, 2021 MR. JUSTICE QAISER RASHID KHAN, CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a K I S T a N

IUB Scores 100% in HEC Online Classes Dashboard The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a k i s t a n Vol. 21 October–December, 2020 Khawaja Ghulam Farid (RA) Seminar and Mehfil-e-Kaafi | 17 Federal Minister for National Food Security Additional IG Police South Punjab Commissioner Bahawalpur Inaugurates Visits IUB Agriculture Farm | 04 Visits IUB | 04 4 New Buses | 09 MD Pakistan Bait ul Mal Visits IUB | 03 Inaugural Ceremony of the Project Punjab Information Technology Board Cut-Flower and Vegetable Production Praises IUB E-Rozgar Center | 07 Research and Training Cell | 13 Honourable Governor Advises IUB to be Student-Centric and Employee-Friendly Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, briefed the Senate meeting of the University. particular, the Governor advised Vice Chancellor, the Islamia Honourable Chancellor about the The Governor appreciated the to University to be more student- University of Bahawalpur made a progress of the Islamia University performance of Islamia University centric and employee-friendly as courtesy call on Governor Punjab of Bahawalpur. Other matters of Bahawalpur and assured of his these ingredients were necessary and Chancellor of the University, discussed included the scheduling wholehearted support to Islamia for world-class universities. Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar. of upcoming Convocation and University of Bahawalpur. In Governor Punjab Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar exchanging views with Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor National Convention on Peaceful University Campuses Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, the Islamia University of Bahawalpur attended the Vice Chancellor’s Convention on peaceful Universities held in joint collaboration of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan and Inter University Consortium for Promotion of Social Sciences. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Gulawar KHAN 2014.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Politics of nationalism, federalism, and separatism: The case of Balochistan in Pakistan Gulawar Khan Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2014. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] POLITICS OF NATIONALISM, FEDERALISM, AND SEPARATISM: THE CASE OF BALOCHISTAN IN PAKISTAN GULAWAR KHAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 Author’s declaration This thesis is carried out as per the guidelines and regulations of the University of Westminster. I hereby declare that the materials contained in this thesis have not been previously submitted for a degree in any other university, including the University of Westminster. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

How Pakistan's Institutionalized Persecution of the Ahmadiyya

Richmond Journal of Global Law & Business Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 2 2011 PAKISTAN’S FAILED COMMITMENT: How Pakistan's Institutionalized Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community Violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Qasim Rashid University of Richmond School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/global Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Qasim Rashid, PAKISTAN’S FAILED COMMITMENT: How Pakistan's Institutionalized Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community Violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 11 Rich. J. Global L. & Bus. 1 (2011). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/global/vol11/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Richmond Journal of Global Law & Business by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAKISTAN’S FAILED COMMITMENT: HOW PAKISTAN’S INSTITUTIONALIZED PERSECUTION OF THE AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY VIOLATES THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS By Qasim Rashid1 “My guiding principle will be justice and complete impartiality, and I am sure that with your support and cooperation, I can look forward to Pakistan becoming one of the greatest Nations of the world.” – Muhammad Ali Jinnah,2* Pakistan’s Founder and First Governor General at the Presidential Address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on 11th August, 1947. ABSTRACT: The United Nations (“UN”) adopted the International Cove- nant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) in 1966 and officially im- plemented it in 1976 to ensure, among other guarantees, that no 1 The author is an American-Muslim human rights activist, writer, and lecturer on American-Islamic issues. -

Special Report No

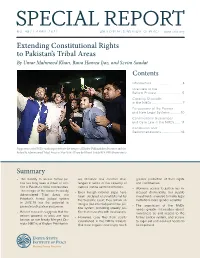

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 492 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Extending Constitutional Rights to Pakistan’s Tribal Areas By Umar Mahmood Khan, Rana Hamza Ijaz, and Sevim Saadat Contents Introduction ...................................3 Overview of the Reform Process ............................ 5 Capacity Shortfalls in the NMDs ...................................7 Perceptions of the Former and New Legal Systems ............ 10 Constitutional Guarantees and Case Law in the NMDs ....... 14 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 18 Supporters of the FATA youth jirga celebrate the merger of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in May 2018. (Photo by Bilawal Arbab/EPA-EFE/ Shutterstock) Summary • The inability to access formal jus- wa Province has created chal- greater protection of their rights tice has long been a driver of con- lenges in terms of the capacity of and civil liberties. flict in Pakistan’s tribal communities. various justice sector institutions. • Women’s access to justice has in- The merger of the former Federally • Even though informal jirgas have creased dramatically, but sizable Administered Tribal Areas into been declared unconstitutional by investment is needed to make legal Pakistan’s formal judicial system the Supreme Court, they remain an institutions more gender sensitive. in 2018–19 has the potential to integral (but informal) part of the jus- promote both justice and peace. • The population of the NMDs tice system, providing speedy jus- needs greater information about, • Recent research suggests that the tice that resonates with local values. awareness of, and access to the reform process in what are now • However, case files from courts formal justice system, and access known as the Newly Merged Dis- established in the NMDs indicate to legal aid and counsel needs to tricts (NMDs) of Khyber Pakhtunkh- that most litigants now enjoy much be improved. -

China Launches Cargo Flight for New Space Station

Fawad asks Opp Bushra launches ISLAMABAD (APP): Minister LAHORE (APP): Prime for Information and Broadcasting Minister's wife Bushra Imran Fawad Saturday asked the opposi- Saturday inaugurated the Shaikh tion parties to focus on construc- Abul Hasan Ash Shadhili tive and positive activities instead Research Hub for promotion of of indulging in undue political ral- Sufism, science and technology in lies. He said the opposition parties the country during a solemn cere- were confused besides their direc- mony here at the the Punjab Sports tion and intentions were in contra- Board (PSB) E-Library building at diction to each others view. Nishter Park Sports Complex. @thefrontierpost First national English daily published from Peshawar, Islamabad, Lahore, Quetta, Karachi and Washington D.C www.thefrontierpost.com Vol. XXXVIII No. 137 Regd. No. 241 SHAWWAL 18 1442 -- SUNDAY, MAY 30 2021 PESHAWAR EDITION 12 PAGES Price. 20 Egypt China launches to Hamas: Pak., Iraq mull cooperation Ceasefire deal cargo flight for must include in security, trade, education prisoner swap BAGHDAD (APP): during the meeting, they port for the sovereignty and try. GAZA CITY (Agencies): Pakistan and Iraq Saturday also discussed the efforts territorial integrity of Iraq, Also, Qureshi met with Hamas has reportedly deliberated over the possi- for Afghan peace as they said a press release. Prime Minister of Iraq new space station received a message from bilities of bilateral coopera- did not want the country to Acknowledging the Mustafa Al-Kadhimi and Egypt that continuing tion in multiple fields be pushed back to the situa- unyielding efforts and sac- proposed the development BEIJING (dpa): China's The Tianzhou 2 is need- are to stay for three months.