The Evolution of Ragtime & Blues to Jazz-A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

INTO the WOODSIN CONCERT Book by James Lapine Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim

PRESENTS INTO THE WOODSIN CONCERT Book by James Lapine Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Directed by Michael Torontow NOVEMBER 14 -16, 2019 Georgian Theatre, Barrie | 705-792-1949 www.tift.ca Presented by | Season Partner Artistic Producer Arkady Spivak INTO THE WOODS Book by James Lapine Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Director Michael Torontow Music Director Wayne Gwillim Choreographer Lori Watson Set and Lighting Designer Joe Pagnan Costume Designer Laura Delchiaro Production Manager Jeff Braunstein Stage Manager Dustyn Wales Assistant Stage Manager Sam Hale Sound Designer Joshua Doerksen Props Master Vera Oleynikova CAST OF CHARACTERS Cast Baker-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Aidan deSalaiz Cinderella’s Prince, Wolf, Lucinda------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Griffin Hewitt Witch---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Alana Hibbert Rapunzel’s Prince, Florinda, Milky White-------------------------------------------------------------------------Richard Lam Baker’s Wife---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Jamie McRoberts Jack’s Mother, Stepmother, Granny, Giant------------------------------------------------------------------Charlotte Moore Jack, Steward------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Justin -

The Dinner Theatre of Columbia

The Dinner TheaTre of Columbia Presents SepTember 11 - november 15, 2015 The Dinner TheaTre of Columbia Presents Ragtime, the Musical Book by Terrence McNally Music by Lyrics by Stephen Flaherty Lynn Ahrens Based on “Ragtime” by E.L. Doctorow Directed & Staged by Toby Orenstein & Lawrence B. Munsey Musical Direction by Ross Scott Rawlings Choreography by Ilona Kesell Set Design by Light Design by Sound Design by David A. Hopkins Lynn Joslin Mark Smedley Costumes by Lawrence B. Munsey Ragtime, the Musical is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International, 421 West 54th Street, New York, NY 10019. 212-541-4684 www.MtiShows.com Video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. Fog & Strobe effects may be used in this performance. Toby’s Dinner Theatre of Columbia • 5900 Symphony Woods Road • Columbia, MD 21044 Box Office (410) 730-8311 • (301) 596-6161 • (410) 995-1969 www.tobysdinnertheatre.com PRODUCTION STAFF Directors .................................................................. Toby Orenstein & Lawrence B. Munsey Music Director/ Orchestrations............................................................ Ross Scott Rawlings Production Manager ................................................................................. Vickie S. Johnson Choreographer .................................................................................................. Ilona Kessell Scenic Designer ........................................................................................ -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

News Release for Immediate

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 30, 2020 OFF-BROADWAY CAST OF “THE WHITE CHIP”, SEAN DANIELS’ CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED PLAY ABOUT HIS UNUSUAL PATH TO SOBRIETY, WILL DO A LIVE ONLINE READING AS A BENEFIT Performance Will Benefit The Voices Project and Arizona Theatre Company and is dedicated to Terrence McNally. In line with Arizona Theatre Company’s (ATC) ongoing commitment to bringing diverse creative content to audiences online, the original Off-Broadway cast of The White Chip will perform a live reading of Artistic Director Sean Daniels’ play about his unusual path to sobriety as a fundraiser for The Voices Project, a grassroots recovery advocacy organization, and Arizona Theatre Company. The benefit performance will be broadcast live at 5 p.m. (Pacific Time) / 8 p.m. (Eastern Time), Monday, May 11 simultaneously on Arizona Theatre Company’s Facebook page (@ArizonaTheatreCompany) and YouTube channel. The performance is free, but viewers are welcome to donate what they can. The performance will then be available for four days afterwards through ATC’s website and YouTube channel. All donations will be divided equally between the two organizations. A New York Times Critics’ Pick, The White Chip was last staged Off-Broadway at 59E59 Theaters in New York City, from Oct. 4 - 26, 2019. Tony Award-nominated director Sheryl Kaller, Tony Award-winning sound designer Leon Rothenberg and the original Off- Broadway cast (Joe Tapper, Genesis Oliver, Finnerty Steeves) will return for the reading. The Off-Broadway production was co-produced with Tony Award-winning producers Tom Kirdahy (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown) and Hunter Arnold (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown). -

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival By Julianna Sonnik The History Behind the Ragtime Festival Scott Joplin - pianist, composer, came to Sedalia, studied at George R. Smith College, known as the King of Ragtime -Music with a syncopated beat, dance, satirical, political, & comical lyrics Maple Leaf Club - controversial, shut down by the city in 1899 Maple Leaf Rag (1899) - 76,000 copies sold in the first 6 months of being published -Memorial concerts after his death in 1959, 1960 by Bob Darch Success from the Screen -Ragtime featured in the 1973 movie “The Sting” -Made Joplin’s “The Entertainer” and other music popular -First Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival in 1974, 1975, then took a break until 1983 -1983 Scott Joplin U.S. postage stamp -TV show possibilities -Sedalia realized they were culturally important, had way to entice their town to companies The Festival Today -38 festivals since 1974 -Up to 3,000 visitors & performers a year, from all over the world -2019: 31 states, 4 countries (Brazil, U.K., Japan, Sweden, & more) -Free & paid concerts, symposiums, Ragtime Footsteps Tour, ragtime cakewalk dance, donor party, vintage costume contest, after-hours jam sessions -Highly trained solo pianists, bands, orchestras, choirs, & more Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival -Downtown, Liberty Center, State Fairgrounds, Hotel Bothwell ballroom, & several other venues -Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation, Ragtime store, website -2020 Theme: Women of Ragtime, May 27-30 -Accessible to people with disabilities -Goals include educating locals about their town’s culture, history, growing the festival, bringing in younger visitors Impact on Sedalia & America -2019 Local Impact: $110,335 -Budget: $101,000 (grants, ticket sales, donations) -Target Market: 50+ (56% 50-64 years) -Advertising: billboards, ads, newsletter, social media -Educational Programs: Ragtime Kids, artist-in-residence program, school visits -Ragtime’s trademark syncopated beat influenced modern America’s music- hip-hop, reggae, & more. -

Sarah EC Maines Marqui Maresca Michael Maresca Dianne Marks

THEATRE AND DANCE FACULTY Cassie Abate Sarah EC Maines Deb Alley Marqui Maresca Ana Carrillo Baer Michael Maresca Natalie Blackman Dianne Marks Greg Bolin Ana Martinez Linda Nenno-Breining Johnny McAllister Kaysie Seitz Brown Amanda McCorkle Elizabeth Buckley Anne McMeeking Trad Burns Brandon R. McWilliams Susan Busa Toby Minor Claire Canavan Jordan Morille Michael Costello Nadine Mozon Michelle Dahlenburg Michelle Nance Tom Delbello Charles Ney Cheri Prough DeVol Michelle Ney Tammy Fife Christa Oliver John Fleming Phillip Owen Misti Galvan William R. Peeler Kevin Gates Bryan Poyser Babs George Aimee Radics Kate Glasheen-Dentino Shannon Richey Brandon Gonzalez Melissa Rodriguez Shelby Hadden Jerry Ruiz Shay Hartung Ishii Sideny Rushing Cathy Hawes Colin Shay Yesenia Herrington Vlasta Silhavy Kaitlin Hopkins LeAnne Smith Randy Huke Shane K. Smith Marcie Jewell Alexander Sterns Erin Kehr Colin D. Swanson Lynzy Lab Caitlin Turnage Laura Lane Neil Patrick Stewart Nick Lawson Scott Vandenberg Eugene Lee Nicole Wesley Clay Liford Yong Suk Yoo STAFF Carl Booker Kim Dunbar Jessica Graham Tina Hyatt Dwight Markus Monica Pasut Jennifer Richards Lori Smith FRONT OF HOUSE STAFF Robert Styers Virtual Theatre Spring 2021 CAST MELCHIOR...............................................................Jeremiah Porter WENDLA.............................................................Kyra Belle Johnson MORITZ............................................................................Riley Clark Department of Theatre and Dance presents ILSE...........................................................................Micaela -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

A Caravan of Culture: Visitors to Emporia, Kansas by Charles E

A Caravan of Culture: Visitors to Emporia, Kansas by Charles E. Webb INTRODUCTION hat do Ulysses S. Grant, "Buffalo Bill" Cody, Susan B. Anthony, Will Rogers, Ethel Barrymore, and Dr. \Verner Von Braun haye in common"? They were W among the hundreds of famous people that have visited EmpOria, Kansas during the past one hundred years. In dividuals and groups of national and international fame, represen ting the arts, seiencl's. education, politics, and entertainment, have pa~sed before Emporia audiences in a century long parade. Since 1879, this formidable array of personalities has provided informa tion and entertainment to Emporia citizens at an average rate of once eaeh fifteen days, The occasional appearanee of a famous personality in a small city may well be considered a matter of historical coineidence. When, however, such visits are numbered in the hundreds, arc fre quent, and persist for a century, it appears reasonable to rank the phenomenon as an important part of that eity's cultural heritage. Emporia, although located in the interior plains, never ae cepted the role of being an isolated community. It seems that the (own's pioneers eonsidered themselves not on the frontier fringi'" of America, but strategically situated near its heart. From the town's beginning, its inhabitants indicated an intention of being informed and participating members of the national and world communities. To better understand why Emporia was able to attract so many distinguished guests, a brief examination of its early development is required. In the formative years of the city's history wc may identify some of the events, attitudes, and preparations Ihat literally set the stage for a procession of renowned visitors. -

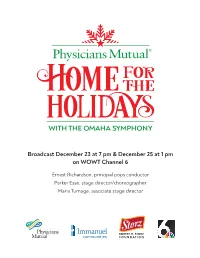

Broadcast December 23 at 7 Pm & December 25 at 1 Pm on WOWT Channel 6

Broadcast December 23 at 7 pm & December 25 at 1 pm on WOWT Channel 6 Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor Parker Esse, stage director/choreographer Maria Turnage, associate stage director ROBERT H. STORZ FOUNDATION PROGRAM The Most Wonderful Time of the Year/ Jingle Bells JAMES LORD PIERPONT/ARR. ELLIOTT Christmas Waltz VARIOUS/ARR. KESSLER Happy Holiday - The Holiday Season IRVING BERLIN/ARR. WHITFIELD Joy to the World TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Mother Ginger (La mère Gigogne et Danse russe Trepak from Suite No. 1, les polichinelles) from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY We Are the Very Model of a God Bless Us Everyone from Modern Christmas Shopping Pair A Christmas Carol from Pirates of Penzance ALAN SILVESTRI/ARR. ROSS ARTHUR SULLIVAN/LYRICS BY RICHARDSON Silent Night My Favorite Things from FRANZ GRUBER/ARR. RICHARDSON The Sound of Music RICHARD RODGERS/ARR. WHITFIELD Snow/Jingle Bells IRVING BERLIN/ARR. BARKER O Holy Night ADOLPH-CHARLES ADAM/ARR. RICHARDSON Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow JULE STYNE/ARR. SEBESKY We Need a Little Christmas JERRY HERMAN/ARR. WENDEL Frosty the Snowman WALTER ROLLINS/ARR. KATSAROS Hark All Ye Shepherds TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Sleigh Ride LEROY ANDERSON 2 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor and resident conductor of the Omaha Symphony, is the artistic leader of the orchestra’s annual Christmas Celebration production and internationally performed “Only in Omaha” productions, and he leads the successful Symphony Pops, Symphony Rocks, and Movies Series. Since 1993, he has led in the development of the Omaha Symphony’s innovative education and community engagement programs. -

SPRING AWAKENING Is Presented by Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

This production contains mature adult content including profanity and violence. It employs the use of chemical fog and includes the smoking of non-tobacco cigarettes. Before the performance begins, please note the exit closest to your seat. Kindly silence your cell phone, pager and other electronic devices. Photography, as well as the videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production, is strictly prohibited. Food and drink are not permitted in the theater. Thank you for your cooperation. SPRING AWAKENING is presented by special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 421 West 54th Street, New York, NY 10019. Phone (212)541.4684. Fax (212)397.4684. www.MTIShows.com. Spring Awakening About the Director Stafford Arima was nominated for an Olivier Award as Best Director for his West End production of Ragtime. He recently directed, Carrie (Off-Broadway), Allegiance (The Old Globe) and Bare (Off-Broadway). Sacramento Music Circus productions include: The King and I, Miss Saigon, Ragtime and A Little Night Music. Other works: Altar Boyz (Off-Broadway); Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris (Stratford Shakespeare Festival), Total Eclipse (Toronto); The Secret Garden (World AIDS Day benefit concert, NYC);The Tin Pan Alley Rag (Off-Broadway); Bowfire (PBS television special); Candide (San Francisco Symphony); A Tribute to Sondheim (Boston Pops); Guys and Dolls (Paper Mill Playhouse); and Bright Lights, Big City (Prince Music Theater, PA). Arima served as associate director for the Broadway productions of Seussical and A Class Act. He studied at York University in Toronto, Canada where he received the Dean’s Prize for Excellence in Creative Work.