Bhupen Khakhar’, in Bhupen Khakhar, in Retrospective Exh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies

972 “William Blake and His Circle” PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies 1780 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXX. The Twelfth (1780) <BB> B. Anon. "Catalogue of Paintings Exhibited at the Rooms of the Royal Academy", Library of the Fine Arts, III (1832), 345-358 (1780) <Toronto>. In 1780, the Blake entry is reported as "W Blake.--315. Death of Earl Goodwin" (p. 353). REVIEW Candid [i.e., George Cumberland], Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 27 May 1780 (includes a criticism of “the death of earl Goodwin, by Mr. Blake”) <BB #1336> 734 Some exhibitions apparently were not accompanied by catalogues and are known only through press-notices of them. 735 See G.E. Bentley, Jr, Sale Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013 put online on 21 Aug 2013 [http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special collections/bentley blake collection/in]. It includes sales of contemporary copies of Blake’s books and manuscripts, his watercolours and drawings, and books (including his separate prints) with commercial engravings. After 2012, I do not report sale catalogues which offer unremarkable copies of books with Blake's commercial engravings or Blake's separate commercial prints. 972 973 “William Blake and His Circle” 1784 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXXIV. The Sixteenth (London: Printed by T. Cadell, Printer to the Royal Academy) <BB> Blake exhibited “A breach in a city, the morning after a battle” and “War unchained by an angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine following”. REVIEW referring to Blake Anon., "The Exhibition. Sculpture and Drawing", Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, Thursday 27 May 1784, p. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

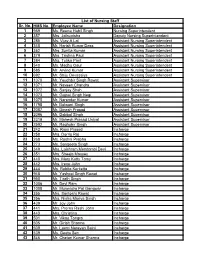

Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs

List of Nursing Staff Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs. Jaibunisha Deputy Nursing Superintendent 3 285 Ms. Vijay A Lal Assistant Nursing Superintendent 4 348 Mr. Harish Kumar Dass Assistant Nursing Superintendent 5 362 Mrs. Sunita Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 6 379 Mrs. Trishna Paul Assistant Nursing Superintendent 7 384 Mrs. Tulika Pant Assistant Nursing Superintendent 8 540 Ms. Madhu Gaur Assistant Nursing Superintendent 9 585 Mr. Arvind Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 10 692 Mr. Shiju Devassiya Assistant Nursing Superintendent 11 1070 Mr. Youdhbir Singh Rawat Assistant Supervisor 12 1071 Mr. Naveen Chandra Assistant Supervisor 13 1072 Mr. Sanjay Shah Assistant Supervisor 14 1073 Mr. Gajpal Singh Negi Assistant Supervisor 15 1075 Mr. Narender Kumar Assistant Supervisor 16 1798 Mr. Balwant Singh Assistant Supervisor 17 2087 Mr. Dinesh Prasad Assistant Supervisor 18 2096 Mr. Dabbal Singh Assistant Supervisor 19 2319 Mr. Mahesh Prasad Uniyal Assistant Supervisor 20 2592 Mr. Raghubir Singh Assistant Supervisor 21 242 Ms. Rajni Prasad Incharge 22 258 Mrs. Dorris Raj Incharge 23 268 Ms. Roshni Prabha Incharge 24 273 Ms. Sangeeta Singh Incharge 25 349 Mrs. Laishram Memtombi Devi Incharge 26 351 Mrs. Sheeja Massey Incharge 27 440 Mrs. Mary Kutty Tomy Incharge 28 442 Mrs. Irene John Incharge 29 444 Ms. Rubita Kerketta Incharge 30 948 Mr. Yashpal Singh Rawat Incharge 31 950 Mr. Tirath Singh Incharge 32 1006 Mr. Devi Ram Incharge 33 1008 Mr. Munendra Pal Gangwar Incharge 34 355 Mrs. Santoshi Rawat Incharge 35 356 Mrs. Nisha Mariya Singh Incharge 36 439 Mr. -

Uttarakhand State Medical/Dental Counselling - 2016 (State Merit List of Registered Candidates Only) NOTE : 1

Uttarakhand State Medical/Dental Counselling - 2016 (State Merit List of Registered Candidates only) NOTE : 1. Merit List is prepared on the basis of NEET All India Rank (Over All Rank) and data of registered candidates verified by CBSE, New Delhi 2. Category/Sub Category will be as filled by candidate and subject to provisional verification of documents, uploaded by the candidate by counselling board and final verification with original documents at the time of admission in the allotted institute. Generated NEET Total NEET All Sub - NEET Roll NEET Combined S. No. Candidate's Name Father's Name Gender Category Marks India Rank Category Number Percentile State Merit Obtained (Over All) Rank 1 AVINASH KUMAR KAUSHAL KUMAR M GEN - 81436829 611 99.977298 160 1 2 ANKITA PANDEY KAILASH CHANDRA PANDEY F GEN - 64503665 591 99.948169 367 2 3 DHAIRYA ANIL KUMAR RAI F GEN - 64905012 580 99.922595 550 3 4 SONALI KORANGA KUNDAN SINGH KORANGA F GEN - 87301508 573 99.897706 745 4 5 SHUBHAM CHAUHAN VINAY CHAUHAN M GEN - 60848106 568 99.876919 880 5 6 ABHINAY PUNDIR HARENDRA SINGH M GEN - 81433043 552 99.781052 1554 6 7 SAKSHI SINGHAL TARUN SINGHAL F GEN - 64500851 552 99.781052 1587 7 8 PRANJAL GULATI ANIL GULATI M GEN - 87202252 550 99.763684 1682 8 9 SIDDHARTH SURI SACHIN SURI M GEN - 64505957 548 99.745085 1789 9 10 SHUBHAM JOSHI JAGDISH CHANDRA JOSHI M GEN - 87203112 542 99.684638 2234 10 11 VIJAY NEGI PURAN SINGH NEGI M GEN - 60822758 541 99.671783 2325 11 12 AAMNA FALAK MAHBUB ALAM F GEN - 64502905 541 99.671783 2337 12 13 AMRIT PANT VIJAY PANT -

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21St Century

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century Neelam Sidhar Wright For my parents, Kiran and Sharda In memory of Rameshwar Dutt Sidhar © Neelam Sidhar Wright, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9634 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9635 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0356 6 (epub) The right of Neelam Sidhar Wright to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations of Film Titles viii 1 Introduction: The Bollywood Eclipse 1 2 Anti-Bollywood: Traditional Modes of Studying Indian Cinema 21 3 Pedagogic Practices and Newer Approaches to Contemporary Bollywood Cinema 46 4 Postmodernism and India 63 5 Postmodern Bollywood 79 6 Indian Cinema: A History of Repetition 128 7 Contemporary Bollywood Remakes 148 8 Conclusion: A Bollywood Renaissance? 190 Bibliography 201 List of Additional Reading 213 Appendix: Popular Indian Film Remakes 215 Filmography 220 Index 225 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the following people for all their support, guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout the course of researching and writing this book: Richard Murphy, Thomas Austin, Andy Medhurst, Sue Thornham, Shohini Chaudhuri, Margaret Reynolds, Steve Jones, Sharif Mowlabocus, the D.Phil. -

20Years of Sahmat.Pdf

SAHMAT – 20 Years 1 SAHMAT 20 YEARS 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements 2 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 YEARS, 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements © SAHMAT, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86219-90-4 Rs. 250 Cover design: Ram Rahman Printed by: Creative Advertisers & Printers New Delhi Ph: 98110 04852 Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust 29 Ferozeshah Road New Delhi 110 001 Tel: (011) 2307 0787, 2338 1276 E-mail: [email protected] www.sahmat.org SAHMAT – 20 Years 3 4 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 Years 5 Safdar Hashmi 1954–1989 Twenty years ago, on 1 January 1989, Safdar Hashmi was fatally attacked in broad daylight while performing a street play in Sahibabad, a working-class area just outside Delhi. Political activist, actor, playwright and poet, Safdar had been deeply committed, like so many young men and women of his generation, to the anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian values that were woven into the rich fabric of the nation’s liberation struggle. Safdar moved closer to the Left, eventually joining the CPI(M), to pursue his goal of being part of a social order worthy of a free people. Tragically, it would be of the manner of his death at the hands of a politically patronised mafia that would single him out. The spontaneous, nationwide wave of revulsion, grief and resistance aroused by his brutal murder transformed him into a powerful symbol of the very values that had been sought to be crushed by his death. Such a death belongs to the revolutionary martyr. 6 PUBLICATIONS Safdar was thirty-four years old when he died. -

Editors Him Chatterjee Pankaj Gupta Mritunjay Sharma Virender Kaushal

[ebook Series 1] Pratibha Spandan Editors Him Chatterjee Pankaj Gupta Mritunjay Sharma Virender Kaushal Emerging Trends in Art and Literature Emerging Trends in Art and Literature 2020 ISBN 978-81-945576-0-9 (ebook) Editors Him Chatterjee Mritunjay Sharma Pankaj Gupta Virender Kaushal Price: FREE OPEN ACCESS Published by Pratibha Spandan Long View, Jutogh, Shimla 171008 Himachal Pradesh, India. email : [email protected] website : www.pratibha-spandan.org © All rights reserved with Pratibha Spandan and authors of particular articles. This book is published open access. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical or other, including photocopy, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s), Editor(s) and the Publisher. The contributors/authors are responsible for copyright clearance for any part of the contents of their article. The opinion or views expressed in the articles are personal opinions of the contributors/authors and are in no sense official. Neither the Pratibha Spandan nor the Editor(s) are responsible for them. All disputes are subject to the jurisdiction of District courts of Shimla, Himachal Pradesh only. 2 Emerging Trends in Art and Literature Dedicated to all knowledge seekers 3 Emerging Trends in Art and Literature PREFACE Present ear is an epoch of multidisciplinary research where the people are not only working across the disciple but have been contributing to the field of academics and research. Art and Literature has been the subject of dialogue from the times of yore. -

A Fragile Inheritance

Saloni Mathur A FrAgile inheritAnce RadicAl StAkeS in contemporAry indiAn Art Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art ·· · 2019 © 2019 All rights reserved Printed in the United States o America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Quadraat Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library o Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mathur, Saloni, author. Title: A fragile inheritance : radical stakes in contemporary Indian art / Saloni Mathur. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identi£ers: ¤¤ 2019006362 (print) | ¤¤ 2019009378 (ebook) « 9781478003380 (ebook) « 9781478001867 (hardcover : alk. paper) « 9781478003014 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: ¤: Art, Indic—20th century. | Art, Indic—21st century. | Art—Political aspects—India. | Sundaram, Vivan— Criticism and interpretation. | Kapur, Geeta, 1943—Criticism and interpretation. Classi£cation: ¤¤ 7304 (ebook) | ¤¤ 7304 .384 2019 (print) | ¤ 709.54/0904—dc23 ¤ record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006362 Cover art: Vivan Sundaram, Soldier o Babylon I, 1991, diptych made with engine oil and charcoal on paper. Courtesy o the artist. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the ¤ Academic Senate, the ¤ Center for the Study o Women, and the ¤ Dean o Humanities for providing funds toward the publication o this book. ¶is title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to the initiative and the generous support o Arcadia, a charitable fund o Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and o the ¤ Library. vii 1 Introduction: Radical Stakes 40 1 Earthly Ecologies 72 2 The Edice Complex 96 3 The World, the Art, and the Critic 129 4 Urban Economies 160 Epilogue: Late Styles 185 211 225 I still recall my £rst encounter with the works o art and critical writing by Vivan Sundaram and Geeta Kapur that situate the central concerns o this study. -

Sl. No. Name of the Candidate Gender M/F Father's Name/ Husband's

List of the applicant who actually appeared in the Technician (T-1) Examination-2016 held on 04-09-2016 Sl. No. Name of the Gender Roll No. Father's Name/ Husband's name Candidate M/F 1 100100001 Rakesh Lathar M Sh. Babu Lal 2 100100002 Abhishek Giri M Sh. Bhupendra Giri Puran Singh 3 100100003 M Sh. Ajit Singh Shekhawat Shekhawat Devendra 4 100100004 M Sh. Madan Lal Solanki Shaktipal Singh 5 100100005 M Sh. Chain Singh Rathore Rathore 6 100100006 Vishakha Pareek F Sh. Satyanarayan Pareek Raghav Singh 7 100100007 M Sh. Hari Charan Meena Meena Shiv Prakash 8 100100013 M Sh. Gordhan Ram Devasi 9 100100014 Bijendra Kumar M Sh. Shree Chand 10 100100015 Neetendra Singh M Sh. Bodu Singh Sawi Singh 11 100100016 M Sh. Sugan Singh Rajpurohit Rajpurohit 12 100100017 Ghanshyam M Sh. Girdhari Lal Amrit Jeet Kaur 13 100100018 F Sh. Chandra Prakash Verma Verma 14 100100019 Deva Ram M Sh. Dalla Ram 1 Sl. No. Name of the Gender Roll No. Father's Name/ Husband's name Candidate M/F Mahesh Singh 15 100100021 M Sh. Nepal Singh Khinchi Kailash Chandra 16 100100022 M Sh. Narsa Ram Meghwal 17 100100024 Jitendra Puri M Sh. Himmat Puri 18 100100028 Rakesh Singh M Sh. Lakhan Singh 19 100100030 Anada Ram M Sh. Banshi Lal Prakash 20 100100031 M Sh. Nathuram Leelawat Leelawat 21 100100032 Ramesh Kumar M Sh. Dana Ram 22 100100034 Laxman Garg M Sh. Amar Lal Garg 23 100100035 Rana Ram M Sh. Joga Ram 24 100100036 Dhirendra Singh M Sh. Puran Singh Priyanka 25 100100037 F Sh. -

Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century Ebook

THE WORLD NEW MADE: FIGURATIVE PAINTING IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY EBOOK Author: Timothy Hyman Number of Pages: 256 pages Published Date: 15 Nov 2016 Publisher: Thames & Hudson Ltd Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780500239452 Download Link: CLICK HERE The World New Made: Figurative Painting In The Twentieth Century Online Read In surveying some of the places where painting has recently been, it is also suggesting where painting should go from here. The book does make a number of important historical points. Andreas Campomar. More The World New Made: Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century Doors open at In The World New Madecritic Timothy Hyman argues that abstraction was just one of the means by which artists renewed pictorial language. Format: Hardback. This event will be followed by a book signing. Yet along with such happy and grateful assent, the book inspires vital arguments around the responsibility of painters, the progress and even the purpose of painting in the modern world. Those students will read this book too; and it might just affect them as he hopes. A major exhibition at Tate Britain offers a welcome opportunity to take in a broad view of an artist who reinvigorated art. He was elected an RA in Reviews The World New Made: Figurative Painting In The Twentieth Century Andreas Campomar. And I did absorb some new information from The stars are for an attractive, well illustrated book. The canon might also be enlarged to include a painter as unfairly neglected as Ken Kiff, who more than holds his own on these pages in exalted company.