Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fruitcake Capital of the World

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Management Faculty Presentations Management, Department of 2013 The Fruitcake Capital of the World Sara J. Grimes Georgia Southern University, [email protected] Michael P. McDonald Georgia Southern University, [email protected] John Leaptrott Georgia Southern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/management-facpres Recommended Citation Grimes, Sara J., Michael P. McDonald, John Leaptrott. 2013. "The Fruitcake Capital of the World." Management Faculty Presentations. Presentation 27. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/management-facpres/27 This presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Management, Department of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Management Faculty Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OC13061 The fruitcake capital of the world Jan Grimes Georgia Southern University Michael McDonald Georgia Southern University John Leaptrott Georgia Southern University Abstract Two different fruitcake companies in the same small town are discussed and their widely different strategies are presented. Each of the entrepreneurs began working with a “master baker” as little boys but later followed different paths to develop a successful fruitcake business. A brief history of the fruitcake is offered as evidence that the product has been around for hundreds of years and will likely not go away anytime soon in spite of the ridicule and humor that has surrounded fruitcakes during the past twenty-five years. Keywords: fruitcake, entrepreneurship, family-owned business, strategy, competition The fruitcake capital OC13061 INTRODUCTION According to legend, the fruitcake, was first made during the Roman Empire. -

Sex and the City 2 Uncovered

ISSN: 1465-1998 WEDDINGCakes WIN A DESIGN SOURCE a glamorous stay Issue 36, autumn 2010 £4.99 in the city for two plus fabulous Over 250 wedding inspirational accessories new designs Hundreds Sex and of top cake designer the City 2 contacts SECRETS UNCOVERED Ron Ben-Israel reveals how he made the star wedding cake SQUIRES KITCHEN MAGAZINE PUBLISHING The UlTimaTe gUide To choosing yoUr wedding cake Sex and the City 2 UnCoVered If you’ve already watched Sex and the City 2 then you’ll have seen the stunning tiered white wedding cake dripping with Swarovski crystals – an inspiration for brides and cake designers alike. We spoke to American cake decorating sensation, Ron Ben-Israel (right), who revealed how he and his team made the star wedding cake. How did it come about that you made the wedding cake for Sex and the City 2? We were contacted by the team of set designers for the movie who had seen our work in the media. We’ve also cooperated in the past with Swarovski Crystal to showcase their newest products on cakes. How did you come up with the design? We were given the parameters by the set designers: an elegant, white, over-the-top wedding setting. Interestingly, the design didn’t call for the use of sugar flowers, for which we are well known; the key words were “frozen water” and “sparkle”. There was to be no colour in the cake, just white, transparency, and reflection of light. We started looking at chandeliers for inspiration, but most of the shapes had too much flare on the bottom to become elegant cakes. -

TEMPTING TARTS Your Choice - 5.99 Strawberry Tart a Butter Tart Filled with Custard and Finished with Freshly Glazed Strawberries

® Owned and operated by the same family for over 56 years. Our one and only location. TEMPTING TARTS Your choice - 5.99 Strawberry Tart A butter tart filled with custard and finished with freshly glazed strawberries. Fruit Tart A butter tart shell filled with custard and finished with an assortment of fruit. Lemon Rush Tart A buttery graham cracker crust filled with a sweet tart lemon filling. Whipped Philly Cream Cheese and vanilla cake finished with a cloud of whipped cream. SWEET SINGLE PASTRIES Almond, Apricot Cannoli Almond Horseshoe & Raspberry Bar A cinnamon shell filled with a Made with sliced almonds and Made with sliced almonds, sweet ricotta cheese filling and almond paste - 4.99 almond paste and a raspberry and chocolate chips - 3.99 apricot filling - 4.99 Black & White Chocolate Ganache Cookie Bowties Chocolate cake and chocolate Thin round sponge cake dipped Made with cream cheese mousse covered with a in fudge icing and white laced dough, pecans and chocolate ganache and fondant - 2.79 brown sugar - 4.99 finished with semi-sweet chocolate chips - 4.99 Napoleons Hamentashen French pastry layered with Your choice of apricot Peanut Butter Bavarian cream and finished or cherry- 3.99 Ganache with fondant icing - 5.49 Chocolate cake and peanut Gourmet Cupcake butter mousse covered with Visit our display case for today’s chocolate ganache and finished variety - 2.99 with peanut butter chips - 4.99 Custard Eclair Cinnamon Stick Finished with fudge icing - 4.99 Made with cream cheese laced dough and rolled with Tiramisu cinnamon sugar - 4.99 Espresso soaked sponge cake filled with a light mascarpone Brownies filling, dusted with cocoa - 4.99 A moist rich brownie and finished with a fudge icing - 2.99 Please stop by and visit our dessert case for additional daily creations not listed on our menu. -

Birthday Cakes: History & Recipes by Mary Gage & James Gage

Birthday Cakes: History & Recipes By Mary Gage & James Gage Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved. No portion of this article may be republished without written permission from the authors. www.NewEnglandRecipes.org History and Origins of Birthday Cakes & Candles The tradition of celebrating a person’s birthday with a birthday cake and lit candles originated in 18 th century Germany. In 1746, Count Ludwig von Zinzendorf of Marienborn Germany celebrated his birthday. Andrew Frey, one of the guests, gave a detailed account of the party: “… the Houses to be illuminated on that day, which was accordingly done. They fetch Waggons full of Boughs, and with them covered the whole inside of the Count’s Hall, which is a hundred feet long, and forty wide … that it looked like an Arbour, and also hung up three brass Chandeliers, each of seven candles. In it also are four Pillars which were hung full of Lights spirally disposed. Wooden Letters above two Feet long were made to form the Name of LUDWIG VON ZINZENDORF, and these being gilded with Gold, were fixed to the Wall amidst a Blaze of Lights. The seats were covered with fine Linen set of with very sightly Ribbons. A Table also was made, representing the initial Letters of the Name of the Person who was the Subject of the Festival; there was a Cake as large as any Oven could be found to bake it, and Holes made in the Cake according to the Years of the Person’s Age, every one having a Candle stuck into it, and one in the Middle; the Outside of the Court was adorned with Festoons and foliage …” [Frey, 1753: 15] In Germany, children’s as well adults’ birthdays were also celebrated with birthday cakes. -

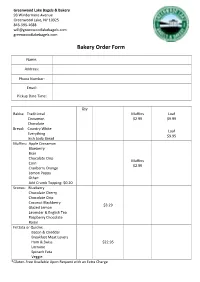

Bakery Order Form

Greenwood Lake Bagels & Bakery 93 Windermere Avenue Greenwood Lake, NY 10925 845-595 -1688 [email protected] Greenwoodlakebagels.com Bakery Order Form Name: Address: Phone Number: Email: Pickup Date Time: Qty Babka: Traditional Muffins Loaf Cinnamon $2.99 $9.99 Chocolate Bread: Country White Loaf EverythinG $9.95 Irish Soda Bread Muffins: Apple Cinnamon Blueberry Bran Chocolate Chip Muffins Corn $2.99 Cranberry OranGe Lemon Poppy Other: Add Crumb Topping: $0.20 Scones: Blueberry Chocolate Cherry Chocolate Chip Coconut Blackberry $3.29 Glazed Lemon Lavender & English Tea Raspberry Chocolate Raisin Frittata or Quiche: Bacon & Cheddar Breakfast Meat Lovers Ham & Swiss $22.95 Lorraine Spinach Feta VeGGie *Gluten-Free Available Upon Request with an Extra CharGe Qty Fruit Pie: Apple Berry Hand Pie 6” Pie 9” Pie Cherry $7.95 $12.95 $17.95 Other: ________________ Add Crumb Topping: +$2.00 Nut Pies: Mixed Nut Hand Pie 6” Pie 9” Pie Pecan $8.95 $13.95 $18.95 Maple Walnut Cream Pies: Banana Coconut Custard Chocolate Hand Pie 6” Pie 9” Pie Lemon MerinGue $8.95 $13.95 $18.95 Key Lime Peanut Butter Booze Infused Pies: Baileys Bourbon Hand Pie 6” Pie 9” Pie Kahlua $9.95 $14.95 $19.95 Jamison Other: Turnovers: Apple Blueberry $3.49 Cherry Cakes: Apple Bourbon Cake $49.99 Black & White Bundt Cake $29.99 Black Forest Cake $29.99 Berry Cheesecake $42.99 Birthday Cake $27.99 Carrot Cheesecake $64.99 Cheesecake $39.99 Lemon Chiffon Cake $24.99 Swiss Roll Cake $39.99 Cupcakes: Dozen Espresso Martini Cupcakes $3.99 $45 Bailey’s Chocolate Cupcakes $3.99 $45 Prosecco Cupcakes $3.99 $45 Chocolate Chocolate Cupcakes $2.99 $33 Vanilla Vanilla Cupcakes $2.99 $33 Cookies/Cake Pops: Almond Joy (LarGe) $3.00 Bunny Cookie with Names $3.00 Banana Chocolate Chip (LarGe) $3.00 Black & White (LarGe) $3.00 Chocolate Chip (LarGe) $3.00 GinGer Snap (LarGe) $3.00 Health Cookie (LarGe) $3.00 Oatmeal Carrot (LarGe) $3.00 Oatmeal Raisin (LarGe) $3.00 Cookie Platter (3 Dozen) $29.99 *Gluten-Free Available Upon Request with an Extra CharGe . -

Cake Handout 2019

sickles market ® Th Chees Love’ Cak Celebratio Cake B th Sickle Marke Baker An untraditional choice for someone who prefers savory to sweet! Perfect for a wedding and any special occasion where you want to WOW your crowd! Detail Our cheese cake is completely customizable. Size and cheese can be designed with our Cheesemongers. Triple Creme Cheeses pictured: Delice de Bourgogne - Jean Grogne Our bakers and cake designers have Brillat Savarin - Delice des Cremiers created decadent cakes for the most important Price upon request. days of your life. We believe every celebration should be as sweet as can be, take a look at our sweetest menu yet! *Celebration Cakes require 72 hour notice* Call our Catering Team to place your order. 1 Harrison Ave, o Rumson Road Little Silver, NJ 732.741.9563 732.741.9563 | sicklesmarket.com Ombr Cak A super fun cake that will bring sweetness, joy, and color to any occasion! Detail 8" Vanilla or chocolate cake with vanilla buttercream filling. Colors can be customized. Starts at $49.99 Fres# Frui Laye Cak We picture this cake for Mother’s Day, Memorial Day Weekend, for 4th of July, or for someone who just loves fruit! Signatur Sickle Birthda Cak This is a versatile birthday cake with a dash of elegance, fun, and flair! Detail Surprise someone special with this rich, creamy delight! Starts at $39.99. 8” Vanilla cake with vanilla buttercream filling and icing, topped with fresh berries. Starts at $59.99 Detail 8" Vanilla or Chocolate Cake with Vanilla or Chocolate Buttercream, Iced Roses and Sprinkles. -

Download Our Cake Pricing Guide Here

Here at Kolatek’s we take pride in making a quality cake that is not overpoweringly sweet. Be it a fruit filled cake, what we call our designer cake like our New Orleans cake, our delightful Ambrosia or just the basic cake and whipped or butter cream cake. Never frozen, made fresh and will leave you wanting more. A perfect accompaniment to a cup of coffee or to celebrate a special occasion. We can also make a special order organic, non-gluten cake or leave out a specific ingredient like eggs or dairy. Most cakes are peanut and tree nut free unless specified. 6” 8” 9” 10” 12” 14” 6-8 8-10 10-12 12-15 15-25 25-35 Regular Cakes $19.99 $24.89 $34.89 $44.89 $63.89 $83.89 Walnut Cake $20.99 $26.89 $38.99 $49.99 $71.89 $93.89 Tiramisu $20.99 $26.89 $38.99 $49.99 $71.89 $93.89 Ambrosia $21.59 $27.59 $39.79 $50.99 $73.39 $95.79 Here at Kolatek’s we take pride in making a quality cake that is not overpoweringly sweet. Be it a fruit filled cake, what we call our designer cake like our New Orleans cake, our delightful Ambrosia or just the basic cake and whipped or butter cream cake. Never frozen, made fresh and will leave you wanting more. A perfect accompaniment to a cup of coffee or to celebrate a special occasion. Below is pricing on sheet cakes which are easier to cut and deal with if you need a cake for more people. -

The Dirty Cheesecake

The Dirty Cheesecake Snickers Bar Cheesecake $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate Covered in snickers bites and drizzled with homemade salted caramel sauce. PB and Jelly Time Cheesecake $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate Covered with creamy peanut butter and drizzled with homemade strawberry jam. Allergy Shot Cheesecake $10.99 New York Cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate topped with brownie bites rolled in graham cracker crumbs and covered with homemade torched marshmallows. Oreo Dream Cheesecake $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate Covered with crushed Oreo drizzled with homemade chocolate and white chocolate sauce. Raspberry Madness Chocolate $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate Triple Chocolate Cheesecake $10.99 rolled in white chocolate chips topped with homemade New York cheesecake dipped Ghirardelli milk chocolate raspberry jam. rolled in brownie bites sprinkled with chocolate sprinkles and drizzled with chocolate sauce. Funfetti Birthday Cheesecake $10.99 Funfetti New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate rolled in rainbow sprinkles and drizzled with chocolate sauce. Dulce de Leche $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate drizzled with caramel and salted caramel sauce. Peanut Butter Finger Cheesecake $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghiradelli milk chocolate rolled into crushed Butterfinger cookies and drizzled with creamy peanut butter. Pecan Pie Cheesecake $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped in Ghirardelli milk chocolate rolled in pecan drizzled with caramel and salted caramel and sprinkled with cinnamon. Oreo Nutella $10.99 New York cheesecake dipped Ghirardelli milk chocolate and rolled in oreo crumbs drizzled with Nutella and topped with oreo. -

Cake Design MELBOURNE ZOO / WERRIBEE OPEN RANGE ZOO

Cake Design MELBOURNE ZOO / WERRIBEE OPEN RANGE ZOO B Y RESTAURANT ASSOCIATES PAGE 2 Children & Christening Designs Children’s birthday cake design Round 8” / 24 serves Square 10” / 50 serves Fondant balloons with animal $260 N/A Full fondant: $230 Full fondant: $350 Confetti or polka dots Buttercream: $180 Buttercream: $260 Freckle cake (100s & 1000s) $130 N/A Striped $210 N/A Oversized cupcake $160 N/A Christening cake design Round 10” / 35 serves Square 10” / 50 serves White fondant, printed plaque $290 $340 with coloured flower border Full fondant: $290 Full fondant: $350 Polka dots Buttercream: $210 Buttercream: $260 Quilted with pearls $290 $350 White fondant, cross with $300 $380 coloured flower border Coloured stripes $260 N/A Additional tiers 4” 6” 8” 10” 12” 14” 16” Round $80 $110 $130 $150 $170 $190 $210 Serves 8 15 30 50 75 95 125 Square $200 $235 $270 N/A N/A N/A N/A Serves 72 98 128 *Additional tiers will be plain coloured fondant as a default. Extra details can be added. Optional extras $ Optional extras $ Fondant bow (3D) Small: $65 Large: $100 Cross 2D: $25 3D: $40 Crown (3D) $35 Lettering $3 per letter Plain: $20 per line Bunting Fondant plaque $70 Lettering: $30 per line Fondant ribbon Small: $65 2D animal $5 per animal (3D topper) Large: $100 Number 2D: $25 3D: $40 PAGE 3 Wedding & Adult Birthday Designs Wedding & Adult 4” 6” 8” 10” 12” 14” 16” birthday Designs Serves 8 15 30 50 75 95 125 Semi-naked $75 $85 $95 $115 $135 $155 $175 Full naked $65 $75 $85 $95 $115 $135 $155 Fully masked $105 $125 $145 $165 $185 $205 $225 +$60 for textured Plain fondant with ribbon $135 $155 $175 $225 $250 $270 $290 Lace or hung ‘pearls’ $165 $175 $185 $295 $320 $350 $380 Fondant ruffles $225 $235 $305 $420 $470 $520 $520 *Barrel cakes are also an option – Double the number of serves and price. -

Cake Flavor Menu

What makes our cakes different? We make everything from scratch- right here in the bake shop, with fresh ingredients and an Artisanal touch. Our buttercream is not too sweet, creamy, and well balanced. We carefully select each ingredient, and never compromise on flavor. -Meredith & The Crew All cakes measure 5 – 5 1/2” in height, our portions are generous and if the dimension does not sound large, our extra servings come in the additional height. Classic Flavors are included in our pricing….. Gourmet Filling +$.60/serving Classic Cake & Filling Flavors: Gourmet Cake Flavor +$.60/serving Classic Flavors are included in our pricing Fresh Berries (market price) +$.75-$1. /serving Choose One Cake Flavor + One Filling + One Frosting Per Gourmet Filling Flavors Tier An additional +$.60/serving Choose (1) One: Classic Cake Flavors: Marshmallow Housemade fluff, folded into vanilla ▪ ▪ Buttercream buttercream with a hint of sea salt! Ultimate Vanilla Devilish Chocolate Smooth, creamy and fabulous! ▪Southern-Style Red Velvet Cream Cheese Classic cream cheese filling with a ▪Alternating Chocolate & Vanilla (2 layers of chocolate cake, touch of vanilla bean Buttercream 2 layers of vanilla cake, alternating) Coffee Milk Buttercream Just like it sounds—coffee milk flavored buttercream! Choose (1) One: Classic Filling: Raspberry Preserves A 70% fruit preserve, classic & not ▪Vanilla Buttercream too sweet ▪Chocolate Ganache Buttercream Lemon Curd Sweet, yet tart smooth lemon filling, nott-too-sweet! Choose (1) One: Classic Frosting: Strawberry Preserves -

Foolproof Cakes: Tried and Tested Recipes for Your Favourite Cakes Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FOOLPROOF CAKES: TRIED AND TESTED RECIPES FOR YOUR FAVOURITE CAKES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Victoria Combe | 160 pages | 21 Aug 2014 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780716023883 | English | London, United Kingdom Foolproof Cakes: Tried and tested recipes for your favourite cakes PDF Book Recipe: Honey-Pineapple Upside-Down Cake This classic, eye-catching dessert is made from start to finish in your cast-iron skillet. The item may have some signs of cosmetic wear, but is fully operational and functions as intended. Straight from the cover of our December issue, this recipe is one of our most popular white cakes for Christmas. Eggs play an important roll in cakes. You can dust cake with powdered sugar if desired. I was intrigued by the idea of a cake using so few ingredients and without needing eggs or dairy. Simply put, it is mixing sugar into butter fat to help produce air bubbles that will expand during baking due to vaporization. Bake this easy but impressive cake for a special occasion. Key Lime Pies and Icebox Cakes are both essential to Southern cooks, and this easy recipe combines the two perfectly. Add to cart. Without a doubt, this is one ingredient I use in all my baking. I cut the recipe in half and it made 2 16 ounce corning ware dishes and a dozen cupcakes. I order a majority of my baking supplies on amazon , including most of my specialty ingredients. Recipe: Mississippi Mud Cake. Bake your way through this definitive guide and enjoy learning about how cake baking works along the way, so you can turn out perfect cakes every time. -

Birthday & Milestone

Birthday & Milestone Birthday & Milestone ©2016 DecoPac ©2016 - DecoPac 20606 Bakery Guide 2016 Selecting Your Cake Size and Cake Format How many guests do you expect? Figure at least one slice of cake per guest. Cakes are traditionally cut in 1" x 2" slices for Tiered cakes. Serving size for sheet cakes is 2" x 2" slices. Some cake toppers may require several days notice due to availability. Cupcakes Single Layer 8" Round Available 6, 12, or 24 count Serves 8 Cupcake Cake Party Combo Cake Cupcake Cake Serves 12 Serves 14 - 16 Serves 24 1/4 Sheet Cake with Image 2-Tier Tier Round Cake 3-Tier Tier Round Cake Serves 24 Available in White or Chocolate layers only Available in White or Chocolate layers only Serves 64 Serves 134 ©2016 DecoPac - 20606 ©2016 DecoPac Birthday & Milestone *There is an additional charge for premium fillings, chocolate curls, and PhotoCake® cakes. Cupcakes can be filled for an additional charge. Ask a Bakery Associate for more details on personalizing your cake and to confirm pricing. Bakery Guide 2016 Customize Your Birthday Cake Choose your favorite options to make your cake one-of-a-kind! Decoration Options Flower - Pink Flower - Purple Flower - Yellow Peony White Large Primary Large 18828 18828 18828 37971 14206 14311 Primary Large Primary Large Orange Mini White Mini Purple Mini Green Mini 14311 14311 7779 7779 7779 7779 Pink Mini Lt Blue Mini Black Mini Yellow Mini Dk Blue Mini Red Mini 7779 7779 7779 7779 7779 7779 Icing Color Options Buttercream White Chocolate Thread Pink Red Neon Yellow Bright Green Blue