Gangster State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressure on Model School to Shape Up

PRESSURE ON MODEL SCHOOL TO SHAPE-UP By Tselane Moiloa KROONSTAD – The Free State provincial government’s education theme during the weeklong celebrations to mark former president Nelson Mandela’s birthday on Wednesday, July 18, has resonated with learners at Bodibeng Secondary School who have been asked to change the path the school has taken in recent years. Located between the dusty townships of Marabastad and Seeisoville, Bodibeng was counted among the best schools in Free State and South Africa during the apartheid regime and the early 90s, after producing luminaries like the late Adelaide Tambo and former Minister of Communications Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri, Mosuioa “Terror” Lekota, MEC Butana Khompela and his soccer-coach brother Steve Khompela. The school, which was founded in 1928 under the name Bantu High, was the only school for black people during the apartheid regime which offered a joint matriculation board qualification instead of the Bantu education senior certificate, putting it on par with the regime’s best schools of the time. Until 1982, it was the only high school in Kroonstad. But the famed reputation took a knock, despite an abundance of resources. “There is obviously a lot of pressure on us to continue with the legacy and it only makes sense that we come through with our promise to do so,” Principal Itumeleng Bekeer said. Unlike many schools which complain about things like unsatisfactory teacher-learner ratios, Bekeer said this is not a concern because the 24 classes from grade eight to 12 have an average 1:24 teacher-learner ratio. However, the socio-economic circumstances in the surrounding townships impact negatively on learners, with a lot coming to school on empty stomachs. -

Address by Free State Premier Ace Magashule on the Occasion of the Department of the Premier’S 2014/2015 Budget Vote Speech in the Free State Legislature

ADDRESS BY FREE STATE PREMIER ACE MAGASHULE ON THE OCCASION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE PREMIER’S 2014/2015 BUDGET VOTE SPEECH IN THE FREE STATE LEGISLATURE 08 JULY 2014 Madam Speaker Members of the Executive Council Members of the Legislature Director General and Senior Managers Ladies and Gentlemen Madam Speaker I am delighted to present the first budget vote for the second phase of the transition taking place at the time when South Africans are celebrating 20 years of democracy. Indeed we are celebrating the remarkable gains we made in a relatively short space of time. In our celebration we cannot forget the brave and noble steps taken by heroes like our former President Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. With July being his birthday month, we pay homage to this giant that fearlessly, fiercely and selflessly fought for South Africans to live in a democratic and open society. It is only befitting that we continue to honour him posthumously by continuing with his legacy of helping people in need and fighting injustice. In the coming days, we will go to various towns and rural areas to launch projects for the upliftment of the needy people. Our programmes will exceed the 67 minutes to enable us to leave indelible and profound memories of tangible change in their lives. In line with President Jacob Zuma’s pronouncement during the 1 State of the Nation Address, we will embark on a massive clean-up campaign in our towns, schools and other areas. Today’s budget speech marks the beginning of a period for radical economic and social transformation. -

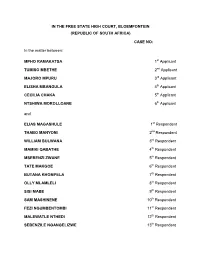

Founding Affidavit Free State High Court-20048.Pdf

IN THE FREE STATE HIGH COURT, BLOEMFONTEIN (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) CASE NO: In the matter between: MPHO RAMAKATSA 1st Applicant TUMISO MBETHE 2nd Applicant MAJORO MPURU 3rd Applicant ELISHA MBANGULA 4th Applicant CECILIA CHAKA 5th Applicant NTSHIWA MOROLLOANE 6th Applicant and ELIAS MAGASHULE 1st Respondent THABO MANYONI 2nd Respondent WILLIAM BULWANA 3rd Respondent MAMIKI QABATHE 4th Respondent MSEBENZI ZWANE 5th Respondent TATE MAKGOE 6th Respondent BUTANA KHOMPELA 7th Respondent OLLY MLAMLELI 8th Respondent SISI MABE 9th Respondent SAM MASHINENE 10th Respondent FEZI NGUMBENTOMBI 11th Respondent MALEWATLE NTHEDI 12th Respondent SEBENZILE NGANGELIZWE 13th Respondent 2 MANANA TLAKE 14th Respondent SISI NTOMBELA 15th Respondent MANANA SECHOARA 16th Respondent SARAH MOLELEKI 17th Respondent MADALA NTOMBELA 18th Respondent JACK MATUTLE 19th Respondent MEGGIE SOTYU 20th Respondent MATHABO LEETO 21st Respondent JONAS RAMOGOASE 22nd Respondent GERMAN RAMATHEBANE 23rd Respondent MAX MOSHODI 24th Respondent MADIRO MOGOPODI 25th Respondent AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 26th Respondent APPLICANTS’ FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I, the undersigned, MPHO RAMAKATSA do hereby make oath and state that: 3 1. I am an adult male member of the Joyce boom (Ward 25) branch of the ANC in the Motheo region of the Free State province, residing at 28 Akkoorde Crescent, Pellissier, Bloemfontein. I am a citizen of the Republic of South Africa with ID No 6805085412084. I am also a member of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (“MKMVA”) and a former combatant who underwent military training under the auspices of the ANC in order to fight for the implementation of democracy and a bill of rights in South Africa. I have been a member of the ANC for the past 25 years. -

Zuma Jailed After Landmark Ruling

InternationalFriday FRIDAY, JULY 9, 2021 Mary Akrami, fighting to keep Afghan women’s Dubai authorities probe port explosion that shook the city Page 11 shelters open Page 18 ESTCOURT, KWAZULU-NATAL: Officials are seen at the Estcourt Correctional Centre, where former South African president Jacob Zuma began serving his 15-month sentence for contempt of the Constitutional Court, in Estcourt, yesterday. — AFP Zuma jailed after landmark ruling South Africa’s first post-apartheid president to be jailed JOHANNESBURG: Jacob Zuma yesterday began a 15-month legal strategy has been one of obfuscation and delay, ultimately weekend that he was prepared to go prison, even though “sending sentence for contempt of court, becoming South Africa’s first in an attempt to render our judicial processes unintelligible,” it me to jail during the height of a pandemic, at my age, is the same post-apartheid president to be jailed after a drama that cam- said. “It is tempting to regard Mr Zuma’s arrest as the end of the as sentencing me to death.” “I am not scared of going to jail for paigners said ended in a victory for rule of law. road” rather than “merely another phase... in a long and fraught my beliefs,” he said. “I have already spent more than 10 years in Zuma, 79, reported to prison early yesterday after mounting a journey,” the foundation warned. Robben Island, under very difficult and cruel conditions”. last-ditch legal bid and stoking defiance among radical supporters As the Wednesday deadline loomed, police were prepared to who had rallied at his rural home. -

Submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture

ACE MAGASHULE OUTA’S SUBMISSION TO THE JUDICIAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO STATE CAPTURE 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................... 0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 PERSONS INVOLVED AND/OR INVITED ......................................................................... 2 THE DEFINITION OF STATE CAPTURE ........................................................................... 3 TIMELINE OF EVENTS ......................................................................................................... 4 12 NOVEMBER 2012 ......................................................................................................... 4 4 MARCH 2013.................................................................................................................... 5 6 MARCH 2013.................................................................................................................... 6 13 MARCH 2013 ................................................................................................................. 6 20 MARCH 2013 ................................................................................................................. 7 23 JULY 2014 ...................................................................................................................... 8 10 NOVEMBER 2014 ........................................................................................................ -

Political Corruption in South Africa by T. LODGE N

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED SOCIAL RESEARCH SEMINAR PAPER TO BE PRESENTED IN THE RICHARD WARD BUILDING SEVENTH FLOOR, SEMINAR ROOM 7003 AT 4PM ON THE 18 AUGUST 1997. TITLE: Political Corruption in South Africa BY T. LODGE NO: 425 Political Corruption in South Africa Tom Lodge 1. Introduction Many people believe that widespread political corruption exists in South Africa. In a survey published by ID AS A in 1996, 46 per cent of the sample consulted felt that most officials were engaged in corruption and only six per cent believed there was clean government1. In another poll conducted by the World Value Survey, 15 per cent of the respondents were certain that all public servants were guilty of bribery and corruption and another 30 per cent thought that most officials were venal2. The IDAS A survey indicated that 41 per cent of the sample felt that public corruption was increasing. Most recently, Transparency International, an international monitoring agency, has reported on a survey which confirms a growing perception among foreign businessmen that official corruption in South Africa is widespread3. These perceptions have probably been stimulated by the proliferation of press reportage on corruption as well as debates between national politicians but the evidence concerns perceptions and in itself is an unreliable indicator of the scope or seriousness of the problem except in so far as the existence of such beliefs can encourage corrupt transactions between officials and citizens. In reviewing the South African evidence this paper will attempt to answer four questions. Is the present South African political environment peculiarly susceptible to corruption? Were previous South African administrations especially corrupt? What forms has political corruption assumed since 1994 and how serious has been its incidence? Finally, does modern South African corruption mainly represent habits inherited from the past or is it a manifestation of new kinds of behaviour? There is general agreement about what constitutes political corruption. -

MOTHER of the NATION: Saint and Sinner

MOTHER OF THE NATION: Saint and Sinner By Isaac Otidi Amuke ‘‘They set up my father as the saint and set up my mother as the sinner,’’ Zindzi Mandela is quoted saying about her famous parents in Pascale Lamche’s film Winnie. Of all front-row ANC freedom fighters – men and women – Winnie Madikizela-Mandela was singled out as the only leader to appear before South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in her personal capacity, where she was implored by Desmond Tutu o apologise to the country for whatever might have gone wrong under her watch. Tutu had argued then that her confession would be good for the country. The ANC employed the use of violence during the anti-apartheid struggle, including deploying bombs in strategic government installations, some of which exploded and killed the wrong targets. It was widely held – and as stated by ANC stalwart Ahmed Kathrada during a BBC HardTalk interview – that some bombings were carried out by unruly ANC cadres. These crimes were pegged not on individuals but on the ANC, which sent senior representatives to the TRC to either explain and defend its position or to apologise. The same collective leniency of being represented by the ANC was not extended to Madikizela-Mandela. The liberation sins attributed to her and those around her were placed squarely at her feet, prominent among them being the 1989 killing of 14-year-old Moeketsi “Stompie” Seipei, who was suspected of being a police informer. ‘‘The one person who kept the fire burning when everyone was petrified,’’ Madikizela-Mandela said of her essential if lonely and thankless role in the anti-apartheid struggle in Lamche’s film, a moment in which moment her eyes got watery. -

Premier Invests in Youth Enterprises

22 February 2013 Premier invests in youth enterprises The premier of the Free State, Ace Magashule , has announced that his office has set aside R2- million to support social enterprise businesses created by the social development department in partnership with the International Labour Organization (ILO) and other government departments. Magashule made this disclosure in Bloemfontein this week at the occasion to present 71 young people from Mangaung and Matjhabeng Local Municipalities with certificates for their participation in social enterprise business plan competition. “Our hope is in our young people, but they must have the required tools. We must ensure that our young people become job creators not job seekers. We are therefore happy with this social enterprise programme.” “They will bring change in their society; the Free State and in Mangaung. It will bring good and sound business to the province. Already I am committing R2-million, we are going to make sure they succeed. The future, hope, prosperity and better life are in reach,” said Magashule. 22 February 2013 Magashule added that young people should strive to be self-reliant because education without hard work is useless. He described himself as a community activist who believes in empowering people through community or social projects. “If you are lazy you cannot grow the economy. I do not know what to do to make South Africa a working nation. Now is the time to reconstruct South Africa. We cannot just sit and not see what we can do for South Africa. The economy will only be changed by your generation,” said Magashule. -

Re Betlatsela

Get Free news in a simple form Fumana Ditaba ka tsela e bobebe Mahala PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICE (PCO) Re betlaTSELA may 2021 issue no.18 Foloing up o or comitments to the peole ANC PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY NEWSLETTER ROOM 18, 155 AB HOSPITAL ROAD, MANGAUNG MUNICIPALITY OFFICES, BOTSHABELO 9781, TELEPHONE NO. 051 5345157 EMAIL: [email protected]. Magashule o eme ‘tlapeng le thellang bomenemene ditjheleteng tsa setjhaba. bothata bo boholo le mokgatlo wa ANC ka Ho thwe bopaki bo tla hlahella bo mora’ hore a hane ho amohela qeto ya ho mo bontshang hantle kamoo Magashule le ba fanyeha mosebetsing hobane a ile a hana ho bang, ho kenyeletswa le Majoro wa emella ka thoko, ka mora’ hore mokgatlo o mehleng wa Phethahatso Masepaleng o laele jwalo; hore ditho tsohle tse qoseditsweng moholo wa Mangaung, Olly Mlaleli, ba diketso tse tlhokolotsi tse kenyeletsang lohileng maqheka le mano ka teng ka manyofonyofo le bobodu di fuwe matsatsi a 30 makgetlo ho utswa dimilione-milione tsa ho emella ka thoko ho tloha mohla qeto. Ha a tjhelete ya mmuso ka bolotsana, ka tlasa dumellane le qeto e nkilweng, mme o hana ho moritaoke wa ho ntsha marulelo a e amohela. Bakeng sa ho ikobela tao eo le ho asbestos dibakeng tse ngata Foreisetata. ikamahanya le dipeelo tsa yona, ke ha a Diqoso di re Makgashule o ile a itjhebisa buisana le mekgatlo ya ditaba, a hlalosa kwana ha manyofonyofo le boshodu di boemo ba hae; hore e ntse e le Mongodi e etswa ka ditjhelete tsa setjhaba. O boetse Moholo wa ANC, mme o tla nne a tswelle pele o qoswa ka ho thola tu, empa a tseba ka ka boikarabelo ba hae le ho etsa mesebetsi ya manyofonyofo, bolotsana le boshodu bo hae. -

Jou Moer Max! - in Reaction to Max Du Preez’S Arrogant Call That the Secretary General of the Anc, Comrade Ace Magashule, Should Be Charged and Imprisoned

ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF ARTICLE: JOU MOER MAX! - IN REACTION TO MAX DU PREEZ’S ARROGANT CALL THAT THE SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE ANC, COMRADE ACE MAGASHULE, SHOULD BE CHARGED AND IMPRISONED By Carl Niehaus* Wow Max, you are quiet a breaker hey. It is so easy-peazy for you to have the solution for all South Africa's problems: Use (the better word is actually abuse) our legal system in order to charge the Secretary General of the ANC, comrade Ace Magashule, with all kinds of conjured up 'crimes', and lock him up in the slammer, so that the President of the ANC, comrade Cyril Ramaphosa, can have a free hand to 'save' our country. You know Max, I actually did not expect anything else from a ‘boerseun’ [boer boy], there from Koppies in the Free State. Subtlety and nuance is really not part of the character make-up of you guys. The son backed you too stubbornly hard there among the iron rocks. You chaps live all the time with hammers and plyers in your hands. Everything that does not suit you, you hammer, twist and brutally beat into a shape that works' for you. Just ask the workers in your farms what happen to them if they do not exactly do what the white 'baas’ [boss] wants them to do... You with your hard ass attitude is no different. So, 'baas’ Max is the hell in because the ANC is not doing what he wants to be done? But I read that you think you have the answer in the person of President Ramaphosa, whom you have convinced yourself is a tame black 'voorman' [supervisor](in the south of the USA they talked about an Uncle Tom), who can be used to rein in the black trouble makers and instigators. -

Ruling Party in Disarray Over Covid-19 Corruption

ACTIONABLE AFRICAN BUSINESS RISK INTELLIGENCE SOUTH AFRICA: 01 September 2020 RULING PARTY IN DISARRAY OVER COVID-19 CORRUPTION A stream of allegations of COVID-19-related corruption has shocked the ruling party and undermined confidence in the government of President Cyril Ramaphosa. The president now faces a challenge from within his own party to remove him early next year and a cabinet reshuffle is imminent. In the meantime, political manoeuvring and graft probes will distract from the coronavirus response, reform of state-owned enterprises, and negotiations with the IMF to avoid a sovereign debt crisis. On 28 August, South Africa?s former president Jacob Zuma accused current President Cyril Ramaphosa of bringing into disrepute the governing African National Congress (ANC) party with his stance against corruption. Zuma?s statement, which is the first time he has publicly rebuked his successor in over two years, came in response to Ramaphosa?s letter to ANC members blaming its leaders for extensive corruption and fraud in the procurement of coronavirus personal protective equipment (PPE). In his letter, Ramaphosa told the party that it stands as ?accused number one.? While the president has survived a recent challenge to his leadership, rival factions in the party are moving to seek his removal from office early next year. EXX AFRICA - SOUTH AFRICA: RULING PARTY IN DISARRAY OVER COVID-19 CORRUPTION Meanwhile, following a conference of the ANC?s top decision-making body on 29 and 30 August, Ramaphosa has been referred to the party?s integrity commission to probe allegations of misleading the country?s parliament about campaign donations he received while running for the ANC leadership in 2017. -

Between Ramaphosa's New Dawn And

Between Ramaphosa’s New Dawn and Zuma’s Long Shadow: Will the Centre hold? Ashwin Desai Abstract Cyril Ramaphosa was sworn in as South Africa’s President in February 2018 after the late-night resignation of Jacob Zuma. His ascendency came in the wake of a bruising battle with Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma that saw him become head of the African National Congress (ANC) by the narrowest of margins. Ramaphosa promised a new dawn that would sweep aside the allegations of the looting of state resources under the Zuma Presidency and restore faith in the criminal justice system. This article firstly looks at the impact that the Zuma presidency has had on South African politics against the backdrop of the Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki years. The article then focuses on Ramaphosa’s coming to power and what this holds for pushing back corruption and addressing the seemingly intractable economic challenges. In this context, I use Gramsci’s ideas of the war of manoeuvre and war of position to provide an understanding of the limits and possibilities of the Ramaphosa presidency. The analysis presented is a conjunctural analysis that as Gramsci points out focusses on ‘political criticism of a day-to-day character, which has as its subject top political leaders and personalities with direct governmental responsibilities’ as opposed to organic developments that lend itself to an understanding of durable dilemmas and ‘give rise to socio-historical criticism, whose subject is wider social groupings – beyond the public figures and beyond the top leaders’ (quoted in Morton 1997: 181). Keywords: Zuma, Ramaphosa, Black Economic Empowerment, State Capture Alternation 26,1 (2019) 214 - 238 214 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/v26n1a10 Between Ramaphosa’s New Dawn and Zuma’s Long Shadow Introduction I was in the crowd in 1994 as the Oryx beat by, the bright flag of a new South Africa fluttering beneath.