Beatriz Ferreyra, Compositrice De Musique Acousmatique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FERREYRA BEATRIZ Profesional

B: No, no nunca fue profesional, nunca llegó a FERREYRA BEATRIZ profesional. Pero tenía un amigo que era CORDOBA 1937 profesional, que era Hernán Pinto que él tocaba en esa época. Una familia de música pero de Pianista de formación Beatriz Ferreyra músicos tradicionales. Yo me fui y lo que yo estudió armonía y análisis con Nadia Boulanger quería hacer era dibujo y pintura. Era más bien y luego música concreta y electrónica en el dibujante. senod el GRM y la RAI, además de composición M: ¿Pero te fuiste a dónde? con Earl Brown, György Ligeti en Darmstadt. B: La primera vez me fui a Estados Unidos pero Como integrante del GRM, Ferreyra colaboró me hicieron volver porque era menor. Me quise en la elaboración del Traité des objets musicaux quedar allá y no me dejaron. Mi madre no me (1966) y los discos de Solfège de l’objet sonore dejó. Y entonces cuando fui mayor de edad dije (1967), de Pierre Schaeffer. Ha sido jurado de me voy a Francia. Yo a Francia me voy, me voy numerosos concursos de música a Europa con amigos. electroacústica. M: Un viaje exploratorio más bien Realiza investigaciones instrumentales B: Si un viaje para irme y en vez de de con Bernard Baschet y se convierte en miembro quedarme un mes me quedé 50 años. del Colegio de Compositores de la GMEB. Sus obras, esencialmente acusmáticas, nacen de M: ¿Por qué? sensaciones, percepciones, sentimientos y una B: Porque hay una presión quizás de la familia. visión personal que ella traduce en sonido. Porque en esa época me sentía que allá no iba a poder hacer nada. -

Database Music a History, Technology, and Aesthetics of the Database in Music Composition

Database Music A History, Technology, and Aesthetics of the Database in Music Composition by Federico Nicolás Cámara Halac A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music New York University May, 2019 Jaime Oliver La Rosa c Federico Nicolás Cámara Halac All Rights Reserved, 2019 Dedication For my mother and father, who have always taught me to never give up with my research, even during the most difficult times. Also to my advisor, Jaime Oliver La Rosa, without his help and continuous guidance, this would have never been possible. For Elizabeth Hoffman and Judy Klein, who always believed in me, and whose words and music I bring everywhere. Finally to Aye, whose love I cannot even begin to describe. iv Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Jaime Oliver La Rosa, for his role in inspiring this project, as well as his commitment to research, clarity, and academic rigor. I am also indebted to committee members Martin Daughtry and Elizabeth Hoffman, for their ongoing guidance and support even at the very early stages of this project, and William Brent and Robert Rowe, whose insightful, thought-provoking input made this dissertation come to fruition. I am also everlastingly grateful to Judy Klein, for always being available to listen and share her listening. As well as to Aye, for her endless support and her helping me maintain hope in developing this project. I would also like to thank my parents, Ana and Hector, who inspired and nurtured my interest in music from a young age, and my sister Flor and my brother Joaquin who were always with me, next to every word. -

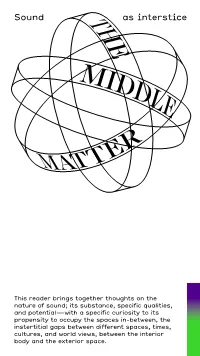

Sound As Interstice

Sound as interstice This reader brings together thoughts on the nature of sound; its substance, specific qualities, and potential—with a specific curiosity to its propensity to occupy the spaces in-between, the instertitial gaps between different spaces, times, cultures, and world views, between the interior body and the exterior space. The Middle Matter Sound as interstice Caroline Profanter, Henry Andersen, and Julia Eckhardt (eds.) Introduction —Caroline Profanter, Henry Andersen, and Julia Eckhardt ........................ 4 Annotations—Enrico Malatesta ...... 11 Sonic Harbour—Séverine Janssen ........ 23 Magical stones, echoes, and music for animals and atmosphere: An interview with Akio Suzuki—Tomoko Sauvage ............................... 29 From the Mechanism of Speech to the Mechanism of Meaning—Lila Athanasiadou .......................... 39 Playing Guqin—Carolyn Chen .............................. 47 Siren Song—Justin Bennett .................................... 53 Togethering, of the open body—Brandon LaBelle .... 65 Towards a Vaginal Listening—Anna Raimondo and Edyta Jarząb .................................................... 75 INTERFACES RESIDENTS Jonathan Frigeri ................................................ 86 ooooo ............................................................ 89 Paulo Dantas ......................................... 92 Melissa E. Logan ......................... 95 Isabelle Stragliati ............. 98 The Middle Matter Alice Pamuk ................ 103 Klaas Hübner ........................... 106 Wederik -

CD Program Notes

CD Program Notes Contents very quick dynamic sounds are op- the Buenos Aires City Conservatory. posed in space to quick, close-range He has composed instrumental and microsounds, sometimes opposing electroacoustic music and his works electronic and acoustic sources. But are performed at international con- his originality, for me, is found in certs and festivals. Part One: Beatriz Ferreyra, the enormous, dynamic general Some of his compositions include: Curator breathing that we can also find in Tres piezas par Orquesta de Camara other of his works. (1958), Movimientos para piano, Elsa Justel puts microsounds into flauta, oboe y clarinette (1964), Estu- Curator’s Note primary place in her compositions, dio en Triptico (electroacoustic mu- including Alba Sud, creating incredi- sic, 1984), Faber Farven Christine Groult, Enrique Belloc, ble, original variations of qualities, (electroacoustic music, 1985), Sin- Roger Cochini, and I studied and colors, forms, and dynamics, not fonia Concertante for digital orches- worked in the 1960s and 1970s with only for each microsound but for tra and synthesizer (1988), Homenaje Pierre Schaeffer and his musical their relationships, articulations, op- a Pierre Schaeffer for live samplers method. Even if Elsa Justel came positions, and so forth. These rela- and synthesizers (1989), Para Bla, un along in the 1980s and searched for tionships occur on the small scale saludo a Barbara Belloc (1993), po- her own way, her work and interest along with larger sounds placed in Pierre (1994), Rugosidades del Incon- in acoustic sounds put her very near different points of audible space. ciente colectivo (1995), Suite the Schaefferian acousmatic ap- For Passagers imminents, Chris- Acusmatica (1995), Objetos Reen- proach. -

'Les Pionniers' - Beatriz Ferreyra

20h 'Les pionniers' - Beatriz ferreyra Le concert des pionniers met, cette fois, à l’honneur Beatriz Ferreyra, grande figure de la musique acousmatique internationale. Annette Vande Gorne, dialoguera ainsi avec Beatriz qui nous emmènera au cœur de son œuvre à travers de nombreux extraits musicaux. Beatriz Ferreyra est née en Argentine, Cordoba en l937. A étudié le piano avec Celia Bronstein (Buenos Aires 1950-56), l'harmonie et l'analyse musicale avec Nadia Boulanger à Paris (1962-63), puis s'est initiée à la musique concrète et éléctronique avec Edgardo Canton (G.R.M., France; R.A.I, Italie l963), et a suivi des cours de composition avec Earl Brown et Georgy Ligeti (Darmstadt l967). A travaillé au Groupe de Recherches Musicales (G.R.M.) du Service de la Recherche de l'O.R.T.F. sous la direction de Pierre Schaeffer (l963-70). Pendant cette periode, outre ses activités musicales et audio-visuelles, a collaboré à la réalisation du travail de recherche de Henri Chiarucci et Guy Reibel: "Le rapport entre la hauteur et la fondamentale d'un son musical", édité en mars l966 dans la revue Internationale d'Audiologie, et à la réalisation des disques du "Solfège de l'Objet Sonore" de Pierre Schaeffer. A eu un rôle pédagogique aux stages du G.R.M. et aux cours du Conservatoire National de Musique de Paris. A été responsable des séminaires interdisciplinaires du Service de la Recherche. A partir de l970, devient compositeur indépendant. Fait des recherches instrumentales avec Bernard Baschet sur ses "Structures sonores" (1970), fait partie du Collège de Compositeurs du Groupe de Musique Expérimentale de Bourges (G.M.E.B. -

What the GRM Brought to Music: from Musique Concre`Te to Acousmatic Music

What the GRM brought to music: from musique concre`te to acousmatic music MARC BATTIER MINT, Maison de la recherche, Universite´ Paris-Sorbonne, 28, rue Serpente, F-75006 Paris E-mail: [email protected] Sixty years ago, musique concre`te was born of the single- alive and the musical creations that it brings about have handed efforts of one man, Pierre Schaeffer. How did the the imprint that is their very own. first experiments become a School and produce so many rich An approach to composition would evolve that works? As this issue of Organised Sound addresses various would be impregnated by a specific thought. Differing aspects of the GRM activities throughout sixty years of from what was taking place in other great studios, the musical adventure, this article discusses the musical thoughts behind the advent and the development of the music created Paris School advanced above all through concepts. It and theoretised at the Paris School formed by the was this wish to adhere to constantly reinforced theory Schaefferian endeavours. Particular attention is given to the that gave the movement its unique character. That said, early twentieth-century conceptions of musical sounds and electroacoustic composition, which was the basis of the how poets, artists and musicians were expressing their quest Paris School, followed the contours of historical for, as Apollinaire put it, ‘new sounds new sounds new contingencies: technological evolution, relations to the sounds’. The questions of naming, gesture, sound capture, public, co-operation with the leading institutions; and processing and diffusion are part of the concepts thoroughly we must not forget the individual paths which tended to revisited by the GRMC, then the GRM in 1958, up to what is branch off in unexpected ways influencing the flow of known as acousmatic music. -

Volume II Interview Transcripts

Deep Listening: The Strategic Practice of Female Experimental Composers post 1945 by Louise Catherine Antonia Marshall Volume II Interview transcripts Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of the Arts London London College of Communication May 2018 Contents Ellen Fullman p. 1 Elsinore, 17 May 2015 Éliane Radigue p. 79 Paris, 4 November 2015 Annea Lockwood p. 150 Leeds, 11 May 2016 Joan La Barbara p. 222 Amsterdam, 17 May 2016 Pauline Oliveros p. 307 London, 23 June 2016 Interview 1 Ellen Fullman Date 17 May 2015 Venue Kulturværftet, Elsinore, Denmark 1 ELLEN FULLMAN Keywords EF = Ellen Fullman KCAI = Kansas City Art Institute LSI = Long String Instrument TW = Theresa Wong Names mentioned Abramovíc, Marina, and Ulay Anderson, Laurie (artist, musician) (performance artists) Ashley, Robert (composer) Bielecki, Bob (Robert) (sound engineer, producer, academic) Buzzarté, Monique (musician) Cage, John (composer) Carr, Tim (curator, The Kitchen, Collins, Nicolas (musician, technician) New York) Deep Listening Band Dempster, Stuart (musician) Dresser, Mark (bass player) Dreyblatt, Arnold (composer) Dukes, Little Laura (entertainer) Feldman, Morton (composer) Ferguson, Ken (ceramicist, Film Video Arts, New York (EF professor, KCAI) installing editing suites) Franklin, C.O. (lawyer, maternal Fuller, Buckminster (architect, grandfather) inventor) Fullman, Peggy and Victor (EF’s Fullman, Robert (Bob, EF’s brother) parents) Gamper, David (musician) Gene Perlowin Associates, New York (EF works as electronics technician) Graney, Pat (choreographer) Hawkins, Screamin’ Jay (blues singer) Hay, Deborah (choreographer) Helms, Jesse (US conservative senator) Hoffman, Hans (artist, EF Ione (Carole Ione Lewis, poet, writer, influenced by his push and pull partner to Pauline Oliveros) theory) Jackson, Mahalia (gospel singer) Jong, Erica (author) King, B.B. -

D53d0ae6fa776b682c5f58f65ac

ERROR the Art of Imperfection Edited by Gerfried Stocker / Christine Schöpf / Hannes Leopoldseder Ars Electronica 2018 Festival for Art, Technology, and Society September 6—10, 2018 Ars Electronica, Linz Editors: Hannes Leopoldseder, Christine Schöpf, Gerfried Stocker Editing: Katia Kreuzhuber, Alexander Wöran Translations: German–English, all texts (unless otherwise indicated): Mel Greenwald English–German: Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber Copyediting: Laura Freeburn Graphic design and production: Cornelia Prokop, Lunart Werbeagentur Minion Typeface: Klavika PEFC Certified This product is from Printed by: Gutenberg-Werbering Gesellschaft m.b.H, Linz sustainably managed forests and controlled Paper: Magno Volume 1,1 Vol., 115 g/m2, 300 g/m2 sources EN www.pefc.org PEFC Certified © 2018 Ars Electronica PEFC Certified PEFC Certified © 2018 for the reproduced works by the artists,This product or is their legalThis product is This product is PEFC Certified from sustainably from sustainably from sustainably This product is from successors managed forests managed forests managed forests sustainably managed and controlled and controlled and controlled forests and controlled sources Published by sources sources sources Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH www.pefc.org www.pefc.org www.pefc.org www.pefc.org Mommsenstrasse 27 10629 Berlin PEFC Certified Germany This product is from Tel. +49 30 3464678-00 sustainably managed Fax +49 30 3464678-29 forests and controlled www.hatjecantz.com sources A Ganske Publishing Group company www.pefc.org Hatje Cantz books are available -

What the GRM Brought to Music: from Musique Concrète to Acousmatic Music

What the GRM brought to music: from musique concrète to acousmatic music (by Marc Battier) Sixty years ago, musique concrète was born of the single-handed efforts of one man, Pierre Schaeffer. How did the first experiments become a School and produce so many rich works? As this issue of Organised Sound addresses various aspects of the GRM activities throughout sixty years of musical adventure, this article discusses the musical thoughts behind the advent and the development of the music created and theoretised at the Paris School formed by the Schaefferian endeavours. Particular attention is given to the early twentieth-century conceptions of musical sounds and how poets, artists and musicians were expressing their quest for, as Apollinaire put it, ‘new sounds new sounds new sounds’. The questions of naming, gesture, sound capture, processing and diffusion are part of the concepts thoroughly revisited by the GRMC, then the GRM in 1958, up to what is known as acousmatic music. Other contributions, such as Teruggi's, give readers insight into the technical environments and innovations that took place at the GRM. This present article focuses on the remarkable unity of the GRM. This unity has existed alongside sixty years of activity and dialogue with researchers of other fields and constant attention to the latter-day scientific, technological and philosophical ideas which have had a strong influence in shaping the development of GRM over the course of its history. What the GRM brought to music: from musique concrète to acousmatic music summarised by Rachel Quigley Electroacoustic music began in its first era at the heart of public radiophonic studio's. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13355-6 — The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music Edited by Nick Collins , Julio d'Escrivan Frontmatter More Information i h e Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music Musicians are always quick to adopt and explore new technologies. h e fast- paced changes wrought by electrii cation, from the microphone via the analogue synthesiser to the laptop computer, have led to a wide range of new musical styles and techniques. Electronic music has grown to a broad i eld of investigation, taking in historical movements such as musique concr è te and elektronische Musik, and contemporary trends such as electronic dance music and electronica. h is book, winner of the 2009 Nicolas Bessarabof Prize, brings together researchers at the forefront of the sonic explorations empowered by electronic technology to provide accessible and insightful overviews of core topics and uncover some hitherto less-publicised corners of worldwide movements. h is updated and expanded second edition includes four entirely new chapters, as well as new original statements from globally renowned artists of the electronic music scene, and celebrates a diverse array of technologies, practices and music. Nick Collins is Reader in Composition at Durham University. His research interests include live computer music, musical artii cial intelligence, and computational musicology, and he is a frequent international performer as composer- programmer- pianist or codiscian, from algoraves to electronic chamber music. Julio d’Escriv á n is Senior Lecturer at the University of Huddersi eld. He researches in i lm and audiovisual music composition and is himself a composer of music for the screen. -

2 Gutenberg's Galaxy

GUTENBERG’S GALAXY Homage to Marshall McLuhan Jana Kluge - Digital Art & Electroacoustic Music Composers: Monty Adkins Danielle Arrigoni Basilio del Boca Gerardo Dirié Beatriz Ferreyra Christine Groult José Halac Jens Hedman Elsa Justel Judy Klein Martin Laliberté Mario Mary José Mataloni Daniel Teruggi Horacio Vaggione Concept 2014 1 about the project ‘Gutenberg's Galaxy’ presents partially an audiovisual version of the multimedia project ‘Gutenberg Galaxias’, realized by Jana Kluge and José Halac in 2010 at the Museo San Alberto Córdoba, Argentina, in collaboration with the Goethe Institute Córdoba. The theme englobes three parts of Marshall McLuhan's pioneering studies of communication technology and its cognitive changes in society: alphabetization, print culture and electronic medias. McLuhan (1911-1980) was a Canadian philosopher, a pioneer of media theories and the author of ‘The Gutenberg Galaxy: The making of Typographic Man’, Toronto University Press, Canada, 1962. 2 Gutenberg’s Galaxy Audio&Visual Performances - Program Universalis Audiovisual fantasies about the global alphabetization Jana Kluge, Video (6:55) 2010, (revised in 2014) José Halac, electronic composition and synchronization, 2010 Video performances: Museo San Alberto/Goethe Institut, Córdoba, Argentina, 2010 KM 93, Auditorium du Conservatoire de Pantin, Paris, France, 2011 McLuhan Centenary Festival, Toronto, Canada, 2011 Festival ‘VideoMusiques’, Musique & Recherche, Bruxelles, Belgique, 2012 Festival ‘Sonami’, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, 2013