14 Formula One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There Aren't Enough Bobbleheads in the World

Feet Up Friday – There aren’t enough bobbleheads in the world Christine: We’ve just had two back-to-back races and now we’ve got back-to-back Feet up Friday’s, this almost never happens anymore. Mr C: It feels like we are underway, the season is go and it’s been non-stop from the first green flag of the year. This is the first break we’ve had, a little bit of downtime for Sidepodcast, but still we are recording a new show for you, that’s how hard we are working this year. Christine: But after two races in a row we’ve got three weeks off now and then there’s another two races and then there’s another three weeks off, it’s just weird scheduling this calendar. Mr C: It’s a crazy calendar, but it makes sense for the people who have to endure it. If you are a Formula 1 team who has to pay personnel to go off overseas, back-to-back races makes a lot of sense. You can cram in a lot of action, you can cram in a lot of racing in a fortnight, and then you can get back to base and save yourself a lot of money and in these troubled economic times, that is essential, so you can’t hold in against… you cannot hold the calendar against the people who have to go out there and live it. Christine: No. And having three weeks off gives us plenty of time to ponder everything that happened in Malaysia because my goodness that was a controversial race. -

January 29, 2020Materials Teijin and Envision Virgin Racing Announce

NEWS RELEASE Teijin and Envision Virgin Racing Announce Multi-Year Partnership Tokyo, Japan, January 29, 2020 --- The Teijin Group and Envision Virgin Racing jointly announced today that they have agreed a multi-year sponsorship contract which will support the team’s participation in the ABB FIA Formula E Championship. Headquartered in Japan with over 170 group companies worldwide, Teijin is a leading technology-driven global group, operating in the fields of high-performance materials including advanced fibers, plastics and composites, healthcare and IT businesses. Envision Virgin Racing has been competing in the all-electric Formula E race series since its inception, becoming one of the sport’s most successful teams with 11 wins and 26 podiums, and energising its “Race Against Climate Change” initiative, while pursuing further sustainable mobility solutions. The Teijin Group and Envision Virgin Racing are now committed to exchanging know- how and complementing each other’s state-of-the-art technologies. In particular, the Teijin Group will develop high-performance materials and products that will help improve the comfort of Envision Virgin Racing drivers. In the future, Teijin will also explore new business opportunities through the development and provision of lightweight, high- performance automotive components, leveraging the freedom of design that will be required for next-generation automobiles. Teijin will also take the opportunity of this sponsorship agreement to raise awareness of the Teijin brand in related industries. “Through ceaseless evolution and ambition, we are aiming to be a company that supports the society of the future by creating new value,” said Jun Suzuki, president and CEO of Teijin Limited. -

F1 Advent Calendar 2010 (Day 16) – Magnanimity

F1 Advent Calendar 2010 (Day 16) – Magnanimity This is Day 16 of the F1 Advent Calendar 2010, brought to you by Sidepodcast. Welcome along! ThanKs for joining me as we looK bacK at the year gone by, picKing out Key moments for a short episode each day. To- day we're looKing at the German Grand Prix, so you can probably guess what this is about. Day 16 - Magna- nimity. The German race weeKend was a big event for a good deal of the F1 paddocK. Michael Schumacher was making his return for his home race, along with five other German drivers. The Mercedes team were also set to enjoy their home weeKend, and Ferrari have long been popular in Germany as well. Hamilton was leading the championship after a good showing at Silverstone, whilst Red Bull were still deal- ing with some unsettled drivers. Throw in some changeable conditions, and you have the recipe for a fasci- nating weeKend. Sebastian Vettel once again tooK a storming pole position, just two thousandths of a second quicKer than second place Fernando Alonso, whilst Felipe Massa slipped into third. At the start of the race, Vettel and Alonso distracted each other, and let Massa scamper past them to take control of the race. Toro Rosso suffered the indignity of their drivers crashing into each other, whilst Force India had some ma- jor pit stop failures. They were expecting Liuzzi in the pitlane, but Sutil came in first, so the wrong tyres went on the wrong car. This is against regulations, and they had to bring the car bacK in to correct the tyre situation. -

Thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS and ANALYSIS from the RACING WORLD

Contents: 2 November 2009 Doubts over Toyota future Renault for sale? Mercedes and McLaren: divorce German style USF1 confirms Aragon and Stubbs Issue 09.44 Senna signs for Campos New idea in Abu Dhabi Bridgestone to quit F1 at the end of 2010 Tom Wheatcroft A Silverstone deal close Graham Nearn Williams to confirm Barrichello and Hulkenberg this week Vettel in the twilight zone thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS AND ANALYSIS FROM THE RACING WORLD Doubts over Toyota future Toyota is expected to announce later this week that it will be withdrawing from Formula 1 immediately. The company is believed to have taken the decision after indications in Japan that the automotive markets are not getting any better, Honda having recently announced a 56% drop in earnings in the last quarter, compared to 2008. Prior to that the company was looking at other options, such as selling the team on to someone else. This has now been axed and the company will simply close things down and settle all the necessary contractual commitments as quickly as possible. The news, if confirmed, will be another blow to the manufacturer power in F1 as it will be the third withdrawal by a major car company in 11 months, following in the footsteps of Honda and BMW. There are also doubts about the future of Renault's factory team. The news will also be a blow to the Formula One Teams' Association, although the members have learned that working together produces much better results than trying to take on the authorities alone. It also means that there are now just three manufacturers left: Ferrari, Mercedes and Renault, and engine supply from Cosworth will become essential to ensure there are sufficient engines to go around. -

Team Lotus Notes Team Lotus Notes Team Lotus Notes

DYNAMIC SPIRITVIBRANT POTENTIAL INCREDIBLE ENERGETIC FAMILY HEROIC AWESOME RACERSRESOLUTE PEDIGREE AGILE PULSATING INSPIREDBRAVE PROGRESSIVESTEADFASTPASSION SPORTING FOCUS INNOVATIVEFRESH LEGENDARYUNDERDOGS 2011 LAUNCH EDITION TEAM LOTUS NOTES TEAM LOTUS NOTES TEAM LOTUS NOTES WELCOME BACK Welcome and thank you. We decided to show the irst pictures of our 2011 challenger in Team Lotus Notes as it is you the fans, who truly power us on and motivate our steps forward. I hope you enjoy the irst taste of our beautiful green and yellow car, and I hope you enjoy reading this; an honest and open insight, written from the heart of the team. When I was asked to pick one word to describe Team Lotus, a million looded into my mind! But eventually I had to come back to where it all started for me – dreams. Team Lotus is about dreams, and those dreams becoming reality. I remember when I was a boy, running a hole in the carpet with my model Lotus Formula One™ car. I had dreams then, I still do, but what I hope to inspire is the belief that if you dare to dream, you can achieve great things. Colin Chapman created the last dynasty and it’s one that inspires me and all my team to do more, think more, be more every day. But now it is time for us to create our own legend. Thank you for sharing this spirit of adventure with us, for being a part of our team, for stepping onto the rollercoaster we’re about to ride and daring to dream. Tony Fernandes ‘ THE GOOD ALWAYS WIN.’ TONY FERNANDES WWW.TEAMLOTUS.CO.UK ‘ THIS YEAR’S CAR IS A MUCH MORE CONTEMPORARY DESIGN. -

NEWSLETTER - March 2013 Wenewsletter Meet Bi-Monthly - on the Fourth Tuesday– September of the Month 8Pm 2006 at the VHRR Club Rooms 30-32 Lexton Rd Box Hill

ABN 97 521 303 894 Incorporated in Victoria Association Number A 0007117 C CLUB PATRON: Sir Jack Brabham OBE AO PO Box 3485 MELBOURNE VIC 3001 Website: www.vhrr.com Reg. No. 57/001 PO Box 3485 MELBOURNEVHRR VICCLUB 3001 ROOMS Website: 30-32 LEXTON www.vhrr.com RD BOX HILLReg. No. 57/001 NEWSLETTER - March 2013 WeNEWSLETTER meet Bi-Monthly - on the Fourth Tuesday– September of the Month 8pm 2006 at the VHRR Club rooms 30-32 Lexton Rd Box Hill. COMINGWe EVENTS meet Bi-Monthly 8 PM at the VHRR Clubrooms 30-32 Lexton Rd Box Hill. Wednesday Lunch Group. Every Wednesday except Christmas Holidays. March 7th-10th Phillip IslandCOMING Classic (CCE) EVENTS ............................................03 9877 2317 March 14th-17th Australian Grand Prix ......................................................03 9787 3640 March 23rd Eddington Sprints ...........................................................03 5468 7295 March 3rd October29th-31st Mallala SCCSA ............................................................... Meridan Motorsort 08Visit/BBQ 8373 4899 April th7th Myrniong Spints ..............................................................03 9827 8124 April *15 23rdOctober MGM Clubrooms ............................................................ Morwell Hillclimb 03 9877 2317 April 28th VHRR Rob Roy ............................................................... Entries Attached 0413 744 337 April 27th-28thnd Morgan Park HRCC ........................................................0412 564 706 May October25th-26th 22 Historic Winton (A7 -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

Friday Press Conference Transcript 23.03.2018

FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE L' AUTOMOBILE 2018 FIA Formula One World Championship Australian Grand Prix Friday Press Conference Transcript 23.03.2018 TEAM REPRESENTATIVES –Toto WOLFF (Mercedes), Maurizio ARRIVABENE (Ferrari), Christian HORNER (Red Bull Racing) PRESS CONFERENCE A question to all of you to start with, what sort of shape are you in relative to each going into this new championship? After all, one of your is likely to be the world champion team at the end of it. Christian, why don’t you start? Christian HORNER: First of all, it’s great to be back in Melbourne, good to be going racing again. It seems like a long winter this one. A positive first session for us, though obviously difficult to read too much into times but you start to get an bit of an idea. You can see Mercedes taking off where they left off; they look in great shape. I think we made good progress with the car over the winter. The drivers seem happy and I’m envisaging a quite tight battle with Maurizio but I’m not sure at the moment what the delta is to Toto’s cars. Toto? Toto WOLFF: Again, like Christian said, it’s good to get started again. We’ve had a pretty good test, much better than last year. But you’re never very sure where that will end up in the first race and the first session was OK, as expected. We didn’t see the Ferraris on the tyres that we have been running, and we need a little bit more time to understand, but I would say it’s a decent start. -

Force India Senza Sorprese Oggi Tocca Alla Mercedes

20 GIOVEDÌ CORRIERE DELLO SPORT 23 FEBBRAIO STADIO MOTO 2017 Ducati riaccende la Superbike Sabato via al Mondiale in Australia: la Rossa concede a Melandri la grande occasione test svoltisi questa settimana di Paolo Scalera nell'isola di Filippo potrebbe team, piloti e moto L'uscita di scena di Max Biag- dar vita a qualche sorpresa. gi e dell'Aprilia ufficiale, alla Il primo rombo di motori Aprilia con Savadori e Laverty fine del 2012, ha privato la Su- anche quest'anno sarà dun- perbike di un po' di attenzio- que della Superbike che cor- Team Piloti Moto ne. Il fuoriclasse romano ha rerà la sua gara inaugurale Kawasaki Jonathan REA (Gbr) Kawasaki ZX-10R provato a tenere acceso il fuo- nel fine settimana a Phillip Tom SYKES (Gbr) Kawasaki ZX-10R co con alcune sue wildcard, Island, in Australia. Rispetto MV Agusta Leon CAMIER (Gbr) MV Agusta F4 1000 terminate anche sul podio, al 2016 le novità sono molte, Red Bull Honda Stefan BRADL (Ger) Honda CBR 1000RR ma è stata la fine di un'era. e tutte interessanti. Nicky HAYDEN (Usa) Honda CBR 1000RR Nelle ultime due stagioni poi Se infatti la casa di Akashi Aruba.it Ducati Chaz DAVIES (Gbr) Ducati Panigale R ci ha pensato il dominio di Jo- fedele al motto “squadra che Marco MELANDRI (Ita) Ducati Panigale R nathan Rea e della Kawasaki vince non si cambia” ripropo- Barni Racing Xavi FORES (Spa) Ducati Panigale R a dare il colpo di grazia a una ne la coppia Rea-Sykes sem- Pedercini Sc-Project Alex DE ANGELIS (Rsm) Kawasaki ZX-10R serie interessantissima per- pre alla guida delle ZX-10R, Althea BMW -

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Simtek Grand Prix

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Welcome to Forgotten F1 Teams – a mini series from Sidepodcast. These shows were originally released over seven consecutive days But are now gathered together in this omniBus edition. Simtek Grand Prix You’re listening to Sidepodcast, and this is the latest mini‐series: Forgotten F1 Teams. I think it’s proBaBly self explanatory But this is a series dedicated to profiling some of the forgotten teams. Forget aBout your Ferrari’s and your McLaren’s, what aBout those who didn’t make such an impact on the sport, But still have a story to tell? Those are the ones you’ll hear today. Thanks should go to Scott Woodwiss for suggesting the topic, and the teams, and we’ll dive right in with Simtek Grand Prix. Simtek Grand Prix was Born from Simtek Research Ltd, the name standing for Simulation Technology. The company founders were Nick Wirth and Max Mosley, Both of whom had serious pedigree within motorsport. Mosley had Been a team owner Before with March, and Wirth was a mechanical engineering student who was snapped up By March as an aerodynamicist, working underneath Adrian Newey. When March was sold to Leyton House, Mosley and Wirth? Both decided to leave, and joined forces to create Simtek. Originally, the company had a single office in Wirth’s house, But it was soon oBvious they needed a Bigger, more wind‐tunnel shaped Base, which they Built in Oxfordshire. Mosley had the connections that meant racing teams from all over the gloBe were interested in using their research technologies, But while keeping the clients satisfied, Simtek Began designing an F1 car for BMW in secret. -

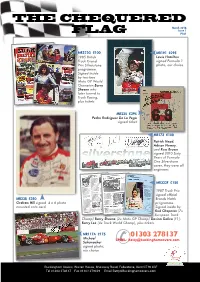

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Massa Full of Hope for Life After Ferrari

SPORTS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2013 Former F1 test pilot De Villota found dead Driver’s body discovered in hotel in Seville MADRID: Former Spanish Formula One thing) because, out of the paddock and her positive outlook,” added Wolff from ROLE MODEL test driver Maria de Villota, one of the out of the motorsport bubble, she was the Japanese Grand Prix in Suzuka. The crash occurred after she had few women to come close to the top of an incredible character, she was a fight- “After the accident she was so behind completed a test run and was returning the sport, has been found dead in a er,” Susie Wolff, a Williams development me and had such a lust for life, she was to the mechanics. The car suddenly hotel in the southern Spanish city of driver who had a test for Williams last so happy to be alive and that she’d sur- accelerated into the back of a team Seville, a police spokeswoman said yes- July and knew De Villota well, told vived it and she had so many great truck with her helmet taking much of terday. De Villota, who lost her right eye Reuters. plans for the future. “She was just an the impact. She was taken to and fractured her skull in a horrific acci- “She had such a spirit for life and incredible lady, no matter about what Cambridge’s Addenbrooke’s hospital dent at a test at Duxford airfield in what she came through was a testa- she did on the racetrack. She was just an and had an emergency operation that England in July last year, had likely died ment to her strength of character and incredible character.” began on a Tuesday afternoon and kept of “natural” causes, the spokeswoman her in theatre until the following morn- said, adding that an investigation was ing.