A Revolutionary Approach to the Eggshell Plaintiff Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: an Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1987 The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines Alan O. Sykes Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan O. Sykes, "The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines," 101 Harvard Law Review 563 (1987). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 101 JANUARY 1988 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW1 ARTICLES THE BOUNDARIES OF VICARIOUS LIABILITY: AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE SCOPE OF EMPLOYMENT RULE AND RELATED LEGAL DOCTRINES Alan 0. Sykes* 441TICARIOUS liability" may be defined as the imposition of lia- V bility upon one party for a wrong committed by another party.1 One of its most common forms is the imposition of liability on an employer for the wrong of an employee or agent. The imposition of vicarious liability usually depends in part upon the nature of the activity in which the wrong arises. For example, if an employee (or "servant") commits a tort within the ordinary course of business, the employer (or "master") normally incurs vicarious lia- bility under principles of respondeat superior. If the tort arises outside the "scope of employment," however, the employer does not incur liability, absent special circumstances. -

Sniadach, the Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B

Boston College Law Review Volume 14 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 2-1-1973 Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B. McDonnell Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Julian B. McDonnell, Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism?, 14 B.C.L. Rev. 437 (1973), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol14/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SNIADACH, THE REPLEVIN CASES AND SELF-HELP REPOSSESSION-DUE PROCESS TOKENISM? JULIAN B. MCDONNELL* Last term, a divided United States Supreme Court invalidated the replevin statutes of Pennsylvania and Florida. In Fuentes v. Shevinl and Parham v. Cortese' (the Replevin Cases), the Court held these statutes unconstitutional insofar as they authorized repossession of collateral through state officials before the debtor was notified of the attempted repossession and accorded an opportunity to be heard on the merits of the creditor's claim. The Replevin Cases involved typical consumer purchases of household pods,' and accordingly raised new questions about the basic relationship between secured creditors and consumer debtors—a relationship upon which our consumer credit economy is based. Creditors have traditionally regarded the right to immediate repossession of collateral after determining the debtor to be in default as the essence of personal property security arrange- ments,' and their standard-form security agreements typically spell out this right. -

Hostile Work Environment and the Objective Reason-Ableness Conundrum

Boston College Law Review Volume 36 Article 2 Issue 2 Number 2 3-1-1995 Hostile Work Environment and the Objective Reason-Ableness Conundrum: Deriving a Workable Framework from Tort Law for Addressing Knowing Harassment of Hypersensitive Employees Frank S. Ravitch Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Frank S. Ravitch, Hostile Work Environment and the Objective Reason-Ableness Conundrum: Deriving a Workable Framework from Tort Law for Addressing Knowing Harassment of Hypersensitive Employees, 36 B.C.L. Rev. 257 (1995), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ bclr/vol36/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOSTILE WORK ENVIRONMENT AND THE OBJECTIVE REASONABLENESS CONUNDRUM: DERIVING A WORKABLE FRAMEWORK FROM TORT LAW FOR ADDRESSING KNOWING HARASSMENT OF HYPERSENSITIVE EMPLOYEESt FRANK S. RAVITCH* Ms. Smith works for a supervisor who does not believe women belong in the workplace. He wants to force her out, but based on the company's harassment policy, he knows he cannot subject her to con- duct that a reasonable person would find severe or pervasive, because that would be illegal discrimination, and his employer would likely take action against him. However, he also knows that she is particularly sensitive to loud noise. She cannot function around loud noise, and becomes extremely nervous. -

Civil Remedies for Sexual Assault

Civil Remedies for Sexual Assault ________________ A Report prepared for the British Columbia Law Institute by its Project Committee on Civil Remedies for Sexual Assault _______________ The members of the Project Committee are: Professor John McLaren - Chair Megan Ellis Dr. Roy O’Shaughnessy Etel Swedahl Professor Christine Boyle Arthur L. Close, Q.C. (Executive Director, BCLI) Jennifer Koshan - Reporter BCLI Report No. 14 June, 2001 British Columbia Law Institute 1822 East Mall, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1Z1 Voice: (604) 822-0142 Fax:(604) 822-0144 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www.bcli.org ----------------------------------------------- The British Columbia Law Institute was created in 1997 by incorporation under the Provincial Society Act. Its mission is to: (a) promote the clarification and simplification of the law and its adaptation to modern social needs, (b) promote improvement of the administration of justice and respect for the rule of law, and (c) promote and carry out scholarly legal research. The Institute is the effective successor to the Law Reform Commission of British Columbia which ceased operations in 1997. ----------------------------------------------- The members of the Institute Board are: Thomas G. Anderson Trudi Brown, Q.C. Arthur L. Close, Q.C. (Executive Director) Prof. Keith Farquhar Sholto Hebenton, Q.C Ravi. R. Hira, Q.C. Prof. Hester Lessard Prof. James MacIntyre, Q.C.(Treasurer) Ann McLean (Vice-chair) Douglas Robinson, Q.C. Gregory Steele (Chair) Etel R. Swedahl Kim Thorau Gordon Turriff (Secretary) ----------------------------------------------- The British Columbia Law Institute gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Law Foundation of British Columbia in carrying out its work. -

A Revolutionary Approach to the Eggshell Plaintiff Rule Steve Calandrillo University of Washington School of Law

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UW Law Digital Commons (University of Washington) University of Washington School of Law UW Law Digital Commons Articles Faculty Publications 2013 Eggshell Economics: A Revolutionary Approach to the Eggshell Plaintiff Rule Steve Calandrillo University of Washington School of Law Dustin E. Buehler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty-articles Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Steve Calandrillo and Dustin E. Buehler, Eggshell Economics: A Revolutionary Approach to the Eggshell Plaintiff Rule, 74 Ohio St. L.J. 375 (2013), https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty-articles/130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eggshell Economics: A Revolutionary Approach to the Eggshell Plaintiff Rule STEVE P. CALANDRILLO* & DUSTIN E. BUEHLER† For more than a century, courts have universally applied the eggshell plaintiff rule, which holds tortfeasors liable for the full extent of the harm inflicted on vulnerable “eggshell” victims. Liability attaches even when the victim’s condition and the scope of her injuries were completely unforeseeable ex ante. This Article explores the implications of this rule by providing a pioneering economic analysis of eggshell liability. It argues that the eggshell plaintiff rule misaligns parties’ incentives in a socially undesirable way. The rule subjects injurers to unfair surprise, fails to incentivize socially optimal behavior when injurers have imperfect information about expected accident losses, and fails to account for risk aversion, moral hazard, and judgment-proof problems. -

Torts Mnemonics

TORTS MNEMONICS 1) Torts are done IN SIN: I – INTENTIONAL harm to a person (e.g., assault, battery, false imprisonment, or the intentional infliction of emotional harm) N – NEGLIGENT conduct causing personal injury, wrongful death, or prop damage S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL harm to property (e.g., trespass, conversion, or tortious interference with a contract) N – NUISANCE 2) Tortious conduct makes you want to SING: S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL conduct N – NEGLIGENT conduct G – GROSS negligence a/k/a reckless conduct 3) A D’s FIT conduct is unreasonable/negligent when P was within the foreseeable zone of danger: F – FAILURE to take reasonable precautions in light of foreseeable risks I – INADVERTENCE T – THOUGHTLESSNESS 4) To establish a negligence claim, P must mix the right DIP: D – DUTY to exercise reasonable care was owed by the D to the injured P and the D breached this duty (for a negligence claim the duty is always to conform to the legal standard of reasonable conduct in light of the apparent risks) I – Physical INJURY to the P or his property (damages) P – P’s injuries were PROXIMATELY caused by the D’s breach of duty 5) A parent is liable only for the torts of a SICK child: S – in an employment relationship where a child commits a tort, while acting as a SERVANT or agent of the parent I – where the parent entrusts or knowingly leaves in the child’s possession an INSTRUMENTALITY that, in light of the child’s age, intelligence, disposition and prior experience, creates an unreasonable risk of harm to -

Thou Shalt Take Thy Victim As Thou Findest Him: Religious Conviction As a Pre-Existing State Not Subject to the Avoidable Consequences Doctrine

File: 5 Loomis.doc Created on: 12/14/06 4:44 PM Last Printed: 12/23/06 1:33 PM 2007] 473 THOU SHALT TAKE THY VICTIM AS THOU FINDEST HIM: RELIGIOUS CONVICTION AS A PRE-EXISTING STATE NOT SUBJECT TO THE AVOIDABLE CONSEQUENCES DOCTRINE Anne C. Loomis* INTRODUCTION As Gwendolyn Robbins’ seventy-year old father drove along a high- way in upstate New York, his car veered off the road at sixty-five miles per hour and turned over in a culvert on nearby farmland.1 After a long day of driving from New York City to Plattsburgh and back, he fell asleep at the wheel.2 Gwendolyn was a passenger in the car, and she suffered a severely damaged left hip and an injury to her right knee.3 Gwendolyn was faced with a choice: she could accept well-recognized and established surgical procedures, which would offer her the prospect of a good recovery and near-normal life; or, she could refuse these procedures and accept the inevi- table necrotic development in the bone structure of her injured limbs, which would ultimately lead to a wheelchair-bound life.4 For Gwendolyn, there was no question which option to take: the wheelchair-bound life. Gwendolyn was a devout Jehovah’s Witness, and she refused the surgical procedures because her religion prohibited blood transfusions, which the surgeries would require.5 When a defendant injures a plaintiff, tort law normally applies the “Avoidable Consequences Doctrine,” or the duty to mitigate damages. The plaintiff is expected to take reasonable steps to minimize her anticipated losses. -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 21 Hearing Date: 01/30/19

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 21 HEARING DATE: 01/30/19 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON TRIAL RE-SETTING * TENTATIVE RULING: * Parties to appear. CourtCall is acceptable if there is no argument on line 2. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON DEMURRER TO COMPLAINT FILED BY BAILEY T. LEE, M.D. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The demurrer of defendant Bailey Lee, M.D., to plaintiffs’ complaint is overruled. Defendant shall file and serve his Answer on or before February 13, 2019. Plaintiffs filed this medical malpractice case on September 6, 2016 against defendant Contra Costa County, several physicians, and Does 1-100. Plaintiffs contend they discovered possible liability on the part of Dr. Lee several years after they suit, based upon conversations with an expert consultant. Shortly thereafter, they filed a Doe amendment on September 25, 2018, naming Dr. Lee as Doe 1. Dr. Lee now demurs to the complaint. He argues that the complaint contains no charging allegations against him and that it is uncertain. (CCP § 403.10 (e), (f).) A party who is ignorant of the name of a defendant or the basis for a defendant’s liability may name that defendant by a fictitious name and amend to state the defendant’s true name when the facts are discovered. (CCP § 474; see Breceda v. Gamsby (1968) 267 Cal.App.2d 167, 174.) If section 474 is properly used, no amendment of the complaint is necessary other than the Doe amendment itself. -

I. A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approac

Torts, Sharkey Fall 2006, Dave Fillingame I. INTRODUCTION A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approach B. Holmes: Two theories of common-law liability: 1. Criminalist (Negligence) 2. “A man acts at his own peril” (strict liability) 3. Judge People by an Objective not a Subjective Standard of Care C. Judge v. Jury in Torts II. INTENTIONAL TORTS A. Elements B. Physical Harms 1. Battery a. Eggshell Skull Rule (Vosburg v. Putney) b. Intent to Act v. Intent to Harm c. “Substantial Certainty” Test (Garratt v. Dailey) d. “Playing Piano” (White v. University of Idaho) e. “Transferred” Intent 2. Defenses to Battery: Consent a. Consent b. Consent: Implied License c. Consent to Illegal Acts 3. Defenses to Battery: Insanity 4. Defenses to Battery: Self-Defense and Defense of Others a. Can be used as a defense when innocent bystanders harmed b. Can be used in defense of third-parties c. Must be proportional force 5. Defenses to Battery: Necessity C. Trespass to Land 1. No Damage is Required, Unauthorized Entry on Land is Enough a. An unfounded claim of right does not make a willful entry innocent. b. Quarum Clausum Fregit 2. Use of Deadly Force in Protection of Property a. Posner: We Must Create Incentives to Protect Tulips and Peacocks. b. Use Reasonable Force: Katko v. Briney (Iowa 1971) 3. Defense of Privilege a. Privilege of Necessity b. “General Average Contribution” c. Conditional (Incomplete) Privilege Vincent v. Lake Erie (Minn. 1910) d. The privilege exists only so long as the necessity does. -

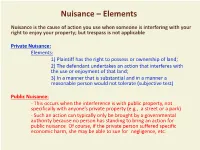

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

South Carolina Damages Second Edition

South Carolina Damages Second Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I DAMAGES IN GENERAL Chapter 1 - DAMAGES IN GENERAL ....................................... 1 A. Necessity of Damages In Actions At Law . 1 1. Actions at Law Versus Actions in Equity . 2 2. Recovery is Premised on the Existence of Damages . 2 3. Restrictions on the Right to Recover Damages . 3 B. Types of Damages and the Purposes They Serve . 4 1. Compensatory Damages ..................................... 4 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 5 3. Punitive Damages .......................................... 6 C. Proof Required for Recovery of Damages . 6 1. Actual Damages............................................ 6 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 9 D. New Trial Nisi, New Trial Absolute, and the Thirteenth Juror . 10 PART II COMPENSATORY DAMAGES Chapter 2 - SOUTH CAROLINA MODIFIED COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE ......... 15 A. Introduction .................................................. 15 B. Contributory Negligence as a Total Bar to Recovery . 16 1. Assumption of the Risk ..................................... 17 2. Last Clear Chance Doctrine ................................. 19 3. Concepts Clouded by the Adoption of Comparative Fault . 19 C. Adoption of Comparative Negligence: Reducing Rather Than Barring Recovery ......................................... 19 1. Apportionment of Responsibility . 20 i Table of Contents 2. Multiple Defendants ....................................... 20 3. Computation of Damages ..................................