General Semantics in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January-December - 2012

JANUARY-DECEMBER - 2012 January 2012 AVOID CONFUSION This world appearance is a confusion as the blue sky is an optical illusion. It is better not to let the mind dwell on it. Neither freedom from sorrow nor realization of one’s real nature is possible as long as the conviction does not arise in us that the world-appearance is unreal. The objective world is a confusion of the real with the unreal. – Yoga Vasishta THE MIND: It is complex. It is logical and illogical, rational and irrational, good and bad, loving and hating, giving and grabbing, full of hope and help, while also filled with hopelessness and helplessness. Mind is a paradox, unpredictable with its own ways of functioning. It is volatile and restless; yet, it constantly seeks peace, stillness and stability. To be with the mind means to live our lives like a roller- coaster ride. The stability and stillness that we seek, the rest and relaxation that we crave for, the peace and calmness that we desperately need, are not to be found in the arena of mind. That is available only when we link to our Higher Self, which is very much with us. But we have to work for it. – P.V. Vaidyanathan LOOK AT THE BRIGHT SIDE: Not everyone will see the greatness we see in ourselves. Our reactions to situations that don’t fit our illusions cause us to suffer. Much of the negative self-talk is based upon reactions to a reality that does not conform to our illusory expectations. We have much to celebrate about, which we forget. -

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present)

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present) STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 Complementary Course of BA English/Economics/Politics/Sociology (CBCSS - 2019 ADMISSION) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Calicut University P.O, Malappuram, Kerala, India 673 635. 19302 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 : MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT) COMPLEMENTARY COURSE FOR BA ENGLISH/ECONOMICS/POLITICS/SOCIOLOGY Prepared by : Module I & II : Haripriya.M Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Scrutinised by : Sunil kumar.G Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Module III&IV : Dr. Ancy .M.A Assistant professor of History School of Distance Education University of Calicut Scrutinised by : Asharaf koyilothan kandiyil Chairman, Board of Studies, History (UG) Govt. College, Mokeri. Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS Module I 4 Module II 35 Module III 45 Module IV 49 Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 3 School of Distance Education MODULE I INDIA AS APOLITICAL ENTITY Battle Of Plassey: Consolodation Of Power By The British. The British conquest of India commenced with the conquest of Bengal which was consummated after fighting two battles against the Nawabs of Bengal, viz the battle of Plassey and the battle of Buxar. At that time, the kingdom of Bengal included the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Wars and intrigues made the British masters over Bengal. The first conflict of English with Nawab of Bengal resulted in the battle of Plassey. -

NEW ARRIVAL BOOKS DECEMBER 2015 Sl.No Acc

AMRITA VISHWA VIDYAPEETHAM UNIVERSITY AMRITAPURI CAMPUS CENTRAL LIBRARY NEW ARRIVAL BOOKS DECEMBER 2015 Sl.No Acc. No Title Author Subject 1 46154 108 Upanishads Balakrishnan,VenganoorSpiritual 2 46055 A Collection of spiritual Discources Giri ji Maharaj, SwamiSpiritual Dayananda 3 46079 A Collection of spiritual Discources GiriJi Maharaj,Swami DayanandSpiritual 4 46018 A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy:BeingRanade,R.D an IntroductionSpiritual to the Thought of the Upanishads 5 45979 A Course of Mathematical Analysis Nickolsky, S.M Mathematics 6 46056 A Dictionary/Panorama of Spiritual Science-AdhyatmaGiriji Maharaj, Vidya:Companion SwamySpiritual Dayanand to Adhyatmic Jeevan Padyawali 7 46116 A Handbook of Hindu Astrology:A Key to ReadPaul, Man's BC Destiny,Past,PresentGeneral and Future 8 45959 A History of India Spear, Percival History 9 46174 A Primer on Spectral Theory Aupetit, Bernard Mathematics 10 45948 A Textbook of Soil Science Daji, J.A Environmental science 11 46187 Aahaarathile Oushadagunangal Raman,K.R General 12 46021 Abhinavagupta's Commentary on the BhagavadMarjanovic,Boris Gita:Gitartha SamgrahaSpiritual 13 45976 Algebra Artin, Mathematics 14 46155 Algebric Geometry II Mumford, David. Mathematics 15 46113 Amma's Sabari: A Collection of 198 Poems Sandhyaa Spiritual 16 46170 An Intensive Course in Tamil:Dialogues, Drills,Exercises, Rajaram,S vocabulary TamilGrammar and word Index 17 45969 An Introduction to Algebraic Topology Rotman Mathematics 18 45972 An Introduction to Complex Function Theory Palka, Bruce -

English Books

December, 2007 I. NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books 000 GENERALITIES 1 Upadhyaya, Abhay Advanced topics in computer / Abhay Upadhyaya and Neelam Upadhyaya.-- Jaipur: Malik, 2006. xiii, 314p.: figs.: tables; 22cm. ISBN : 81-799 8-006-9. 006 P6 C62760 100 PHILOSOPHY AND PSYCHOLOGY 2 Kulkarni, V.M. Outline of Abhinavgupta's aesthetics / V.M. Kulkarni.-- Ahmedabad: Saraswati Pustak Bhandar, 1998. viii, 110p.; 25cm. (Saraswati Oriental Research Sanskrit Series; 13). 111.85 N8 C62792 3 Balasundaram, S. Universal tables of houses: based on Sayana or tropical zodiac system / S. Balasundaram and A.R. Raichur.--5th ed.-- Madras: Krishnamurti Publications, 2006. xlv, 244p.: figs.; 21cm. 133.52 P6 C62785 4 Sachdev, S.K. Some essays on spiritual physics: the laws of nature / S.K. Sachdev.-- Chandigarh: New Era International, 2006. 106p.; 22m. ISBN : 81-290-0 020-2. 133.91 P6 C62769 5 Swami Sukhabodhananda Roar your way to excellence: self empowerment made easy / Swami Sukhabodhananda.-- Bangalore: Prasanna Trust, 2006. 207p.: plates; 22cm. 158.1 P6 C62573 6 Sri Aurobindo: a collection of seminar papers.--rev. ed.-- Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, 2004. ix, 52p.; 22cm. 181.4 P4 C62593 7 Swami, Maha Krishna Years in the presence of Ramana my master / Maha Krishna Swami; edited by A.R. Natarajan.-- Bangalore: Ramana Maharshi Centre for Learning, 2006. vii, 157p.; 24cm. ISBN : 81-88261-52-1. 181.4 P6 C62591 8 Nagendra, H.R. The science of emotion's culture: Bhakti yoga / H.R. Nagendra.-- Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana, 2000. xiv, 197p.: illus.; 22cm. 181.45 P0 C62540 9 Chetty, C.K. -

THE SUPERLIST of FUN LINES and FAMOUS QUOTATIONS 10Th

This file contains 5858 lines from my private collection beginning with the letter “T”. More to follow in due time. Enjoy! THE SUPERLIST OF FUN LINES AND FAMOUS QUOTATIONS 10th. revised edition Compiled by Christer Sundqvist 1987-2005 Christer Sundqvist Neptunuksenkatu 3 FIN-21600 PARAINEN FINLAND TEL: int +358-40-7529274 e-Mail: [email protected] The trouble with most of us is that we would rather be ruined by praise than saved by criticism. Norman Vincent Peale Some fun lines and famous quotations 'T is but a part we see, and not a whole. Alexander Pope (1688-1744) 'T is pleasant, sure, to see one's name in print; / A book 's a book, although there 's nothing in 't. Lord Byron (1788-1824) 'T is well to be merry and wise, / 'T is well to be honest and true; / 'T is well to be off with the old love / Before you are on with the new. Maturin Tact: Changing the subject without changing the mind. Tact consists in knowing how far to go too far. Jean Cocteau Tact is after all a kind of mind reading. Sarah Orne Jewett Tact is one of the first mental virtues, the absence of which is often fatal to the best of talents; it supplies the place of many talents. William Gillmore Simms Tact is rubbing out another's mistake instead of rubbing it in. Tact is the ability to describe others as they see themselves. Abraham Lincoln Tact is the ability to let the other man have your own way. -

Complete Catalogue 2020

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2020 N O N - F I C T I O N | B U S I N E S S | F I C T I O N JAICO PUBLISHING HOUSE JAICO PUBLISHING HOUSE Trade Publishing Sales and Distribution Division While self-help, religion & philosophy, In addition to being a publisher and distributor of its mind/body/spirit, and business titles form the own titles, Jaico is a major national distributor for cornerstone of our non-fiction list, we publish an books of leading international and Indian publishers. exciting range of travel, current affairs, biography, With its headquarters in Mumbai, Jaico has and popular science books as well. branches and sales offices in Ahmedabad, Our renewed focus on popular fiction is evident in Bangalore, Bhopal, Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, our new titles written by a host of fresh young Kolkata and Lucknow. Our sales team of over 40 talent from India and abroad. executives, along with our growing marketing team, ensure that books reach all urban and rural parts of the country. Translations Division Jaico’s Translations Division translates selected Corporate Sales and Customization English content into nine Indian languages. As readership in regional languages continues to grow This division specializes in the adaptation of Jaico rapidly, we endeavour to make our content content for institutional and corporate use. accessible to book lovers in all major Indian languages. Contents Robin Sharma 2 Self-Help 3 Relationships, Pregnancy & Parenting 14 Health & Nutrition 16 Mind, Body & Spirit 18 Religion & Philosophy 21 Popular Science 31 History, Biography & Current Affairs 33 Business 37 Test Prep 46 Fiction 48 Children’s Books 54 ESTABLISHED IN 1946, Jaico is the publisher of world-transforming authors such as Robin Sharma, Stephen Hawking, Devdutt Pattanaik, Sri Sri Paramahansa Yogananda, Osho, The Dalai Lama, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, Sadhguru, Radhakrishnan Pillai, Deepak Chopra, Jack Canfield, Eknath Easwaran, Khushwant Singh, John Maxwell and Brian Tracy. -

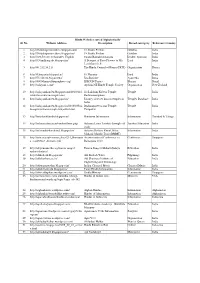

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Nonattachment and Ethics in Yoga Traditions

This is a repository copy of "A petrification of one's own humanity"? Nonattachment and ethics in yoga traditions. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85285/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Burley, M (2014) "A petrification of one's own humanity"? Nonattachment and ethics in yoga traditions. Journal of Religion, 94 (2). 204 - 228. ISSN 0022-4189 https://doi.org/10.1086/674955 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ “A Petrification of One’s Own Humanity”? Nonattachment and Ethics in Yoga Traditions* Mikel Burley / University of Leeds In this yogi-ridden age, it is too readily assumed that ‘non-attachment’ is not only better than a full acceptance of earthly life, but that the ordinary man only rejects it because it is too difficult: in other words, that the average human being is a failed saint. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Spiritual Website Follow

Spiritual Website http://www.speakingtree.in/ Follow the masters http://www.speakingtree.in/masters http://www.spiritualgateway.org/ Spiritual articles http://www.speakingtree.in/spiritual-articles Meet the seekers http://www.speakingtree.in/seekers Join the discussion http://www.speakingtree.in/spiritual-forums Spiritual Forums http://www.speakingtree.in/spiritual-forums Follow, Speaks, Seek and share with the masters http://www.speakingtree.in/srisri.ravishankar Sri Sri Ravi Shankar official web:- http://srisriravishankar.org/ http://www.artofliving.org/ http://www.speakingtree.in/deepakchopra1 Deepak Chopra https://www.deepakchopra.com/ http://www.speakingtree.in/sadhgurujaggi.vasudev Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev Only when you are in touch with the innermost core of who you are, you live a complete life – Sadhguru http://sadhguru.org/ • • • http://www.speakingtree.in/ashutoshmaharaj Ashutosh Maharaj Ji http://divinelight.info/index.html http://www.speakingtree.in/swamisukhabodhananda Swami Sukhabodhananda Peaks and valleys of life http://www.swamisukhabodhananda.net/ http://www.speakingtree.in/meena.om Meena Om Pranam movement dedicated to establish nature’s law of truth, love and light by the spiritual realization of ever-evolving universal pranam is a movement dedicated to establish nature’s law. http://pranam.org.in/ http://www.speakingtree.in/osho1 Osho “To leave oneself totally in the hands of God in utter surrender and trust is to be religious, is to be meditative, is to be prayerful.” http://www.osho.com/ http://www.oshoworld.com/ -

English Books

June 2006 I. NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books 000 GENERALITIES 1 Fadia, Ankit The ethical hacking guide to corporate security / Ankit Fadia.-- Delhi: Macmillan India, 2004. xviii, 250p.: tables: illus.; 24x18.5cm. ISBN : 1403-92445-7. 005.8 FAD-et B169714 2 Jeevan, V.K.J. Computers @ libraries / V.K.J. Jeevan.-- New Delhi: Ess Ess Publications, 2006. 506p.: figs.: tables: boxes; 22cm. Bibliography: p.476-494. ISBN : 81-7000-445-4. 025.04 JEE-c B174015 3 Chilana, Rajwant Singh, ed. Digital information resources and networks on India / edited by Rajwant Singh Chilana...[et.al].-- New Delhi: UBS Publishers Distributors, 2006. 264p.: figs.: plates: tables; 24cm. Essays in honour of Professor Jagindar Singh Ramdev on his 75th birthday. ISBN : 81-7476560-3. 025.040954 CHI-d B174220 4 Chatterji, Rimi B. Empires of the mind: a history of the Oxford University Press in India under the Raj / Rimi B. Chatterjee.-- New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006. v, 469p.: plates; 21.7cm. Bibliography: p.447-450. ISBN : 0-19-567474-x. 070.50954 P6 B174461 5 Gandhi, P. Jegadish Dr. Abdul Kalam's futuristic India / P. Jegadish Gandhi.- New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 2006. xxxiii, 166p.; 22cm. Bibliography: p.162-163. ISBN : 81-7629-839-5. 080 ABD-g B174040 6 Condolence messages on the passing away of Shri G.M.C. Balayogi, Speaker, Lok Sabha/ compiled by Table Office (B), Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi: [2006 ]. 108p.; 30.5cm. R 080 BAL-c C61030 (Ref.) 7 Bimal Prasad,ed. Jayaprakash Narayan: selected works / edited by Bimal Prasad; foreword by K.Jayakumar.-- New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 2005. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore