Multicultural Capitalism and the Canadian Literary Prize Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury

1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS View this email in your browser Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury January 13, 2020 (Toronto, Ontario) – Elana Rabinovitch, Executive Director of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, today announced the five-member jury panel for the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Prize. The 2020 jury members are: Canadian authors David Chariandy, Eden Robinson and Mark Sakamoto (jury chair), British critic and Editor of the Culture segment of the Guardian, Claire Armitstead, and Canadian/British author and journalist, Tom Rachman. Some background on the 2020 jury: https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 1/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS Claire Armitstead is Associate Editor, Culture, at the Guardian, where she has previously acted as arts editor, literary editor and head of books. She presents the weekly Guardian books podcast and is a regular commentator on radio, and at live events across the UK and internationally. She is a trustee of English PEN. David Chariandy is a writer and critic. His first novel, Soucouyant, was nominated for 11 literary prizes, including the Governor General’s Award and the Scotiabank https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 2/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Brother Subscribe GillerPast Prize. His Issues second novel, , was nominated for fourteen prizes, winningTranslate RS the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and the Toronto Book Award. -

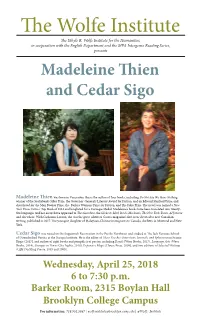

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents Madeleine Thien and Cedar Sigo Madeleine Thien was born in Vancouver. She is the author of four books, including Do Not Say We Have Nothing, winner of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Governor-General’s Literary Award for Fiction, and an Edward Stanford Prize; and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and The Folio Prize. The novel was named a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2016 and longlisted for a Carnegie Medal. Madeleine’s books have been translated into twenty- five languages and her essays have appeared in The Guardian, the Globe & Mail, Brick, Maclean’s, The New York Times, Al Jazeera and elsewhere. With Catherine Leroux, she was the guest editor of Granta magazine’s first issue devoted to new Canadian writing, published in 2017. The youngest daughter of Malaysian-Chinese immigrants to Canada, she lives in Montreal and New York. Cedar Sigo was raised on the Suquamish Reservation in the Pacific Northwest and studied at The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute. He is the editor of There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera on Joanne Kyger (2017), and author of eight books and pamphlets of poetry, including Royals (Wave Books, 2017), Language Arts (Wave Books, 2014), Stranger in Town (City Lights, 2010), Expensive Magic (House Press, 2008), and two editions of Selected Writings (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003 and 2005). Wednesday, April 25, 2018 6 to 7:30 p.m. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Death, Animals, and Ethics in David Bergen's the Time in Between

Document generated on 09/26/2021 1 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Death, Animals, and Ethics in David Bergen’s The Time in Between Katie Mullins Volume 38, Number 1, 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl38_1art013 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mullins, K. (2013). Death, Animals, and Ethics in David Bergen’s The Time in Between. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 38(1), 248–266. All rights reserved, ©2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Death, Animals, and Ethics in David Bergen’s The Time in Between Katie Mullins eath is a dominating presence in David Bergen’s Giller Prize-winning novel The Time in Between (2005). Although Charles Boatman’s suicide lies at the centre of the narrative, Dthe novel — and Charles himself — is also haunted by other deaths: the death of Charles’s ex-wife, Sara, the deaths of innocents in Vietnam, and the deaths of animals. It rotates around various absences and, as is frequently the case in Bergen’s fiction, highlights individual suffering and alienation within the family unit1: Charles returns to Vietnam in the hope of ascribing meaning to the “great field of nothing” that he has experienced since the war (38), while two of his children, Ada and Jon, travel to Vietnam to search for their missing father only to discover he has committed suicide. -

Download Full Issue

191CanLitWinter2006-4 1/23/07 1:04 PM Page 1 Canadian Literature/ Littératurecanadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number , Winter Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Laurie Ricou Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Kevin McNeilly (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New, Editor emeritus (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–2003) Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität Köln Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Leslie Monkman Queen’s University Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Élizabeth Nardout-Lafarge Université de Montréal Ian Rae Universität Bonn Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Penny van Toorn University of Sydney David Williams University of Manitoba Mark Williams University of Canterbury Editorial Laura Moss Playing the Monster Blind? The Practical Limitations of Updating the Canadian Canon Articles Caitlin J. Charman There’s Got to Be Some Wrenching and Slashing: Horror and Retrospection in Alice Munro’s “Fits” Sue Sorensen Don’t Hanker to Be No Prophet: Guy Vanderhaeghe and the Bible Andre Furlani Jan Zwicky: Lyric Philosophy Lyric Daniela Janes Brainworkers: The Middle-Class Labour Reformer and the Late-Victorian Canadian Industrial Novel 191CanLitWinter2006-4 1/23/07 1:04 PM Page 2 Articles, continued Gillian Roberts Sameness and Difference: Border Crossings in The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party Poems James Pollock Jack Davis Susan McCaslin Jim F. -

Bukowski Agency Backlist Highlights

the bukowski agency backlist highlights 2010 www.thebukowskiagency.com CONTENTS Anita Rau Badami . 2 Judy Fong Bates . 4 Alan Bradley . 6 Catherine Bush . 8 Abigail Carter . 9 Wayson Choy . 10 Austin Clarke . 12 George Elliott Clarke . 14 Anthony De Sa . 15 John Doyle . 16 Liam Durcan . 17 Anosh Irani . 18 Rebecca Eckler . 20 Paul Glennon . 21 Ryan Knighton . 22 Lori Lansens . 24 Sidura Ludwig . 26 Pearl Luke . 27 Annabel Lyon . 28 D .J . McIntosh . 30 Leila Nadir . 31 Shafiq Qaadri . 32 Adria Vasil . 32 Eden Robinson . 33 Kerri Sakamoto . 34 Sandra Sabatini . 36 Cathryn Tobin . 37 Cathleen With . 38 CLIENTS . 39 CO-AGENTS . 40 Anita RAu BadamI Can You Hear the Nightbird Call? Can You Hear the Nightbird Call? traces the epic trajectory of a tale of terrorism through time and space 95,000 words hardcover / Finished books available RIGHTS SOLD Canada: Knopf, September 2006 Italy: Marsilio, Spring 2008 France: Éditions Philippe Rey, India: Penguin, January 2007 March 2007 Australia: Scribe, March 2007 Holland: De Geus, Spring 2008 • Longlisted for the 2008 IMPAC Dublin Literary Award • Shortlisted for the Ontario Library Association 2007 Evergreen Awards The Hero’s Walk The Hero’s Walk traces the terrain of family and forgiveness through the lives of an exuberant cast of characters bewildered by the rapid pace of change in today’s India 368 pages hardcover / Finished books available RIGHTS SOLD US: Algonquin, 2001 Canada: Knopf, 2000 US: Paperback: Ballantine Greece: Kastaniotis Editions UK: Bloomsbury, 2002 Poland: Wydawnictwo Dialog France: -

Fall 2013 / Winter 2014 Titles

INFLUENTIAL THINKERS INNOVATIVE IDEAS GRANTA PAYBACK THE WAYFINDERS RACE AGAINST TIME BECOMING HUMAN Margaret Atwood Wade Davis Stephen Lewis Jean Vanier Trade paperback / $18.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 ANANSIANANSIANANSI 978-0-88784-810-0 978-0-88784-842-1 978-0-88784-753-0 978-0-88784-809-4 PORTOBELLO e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 978-0-88784-872-8 978-0-88784-969-5 978-0-88784-875-9 978-0-88784-845-2 A SHORT HISTORY THE TRUTH ABOUT THE UNIVERSE THE EDUCATED OF PROGRESS STORIES WITHIN IMAGINATION FALL 2013 / Ronald Wright Thomas King Neil Turok Northrop Frye Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $14.95 978-0-88784-706-6 978-0-88784-696-0 978-1-77089-015-2 978-0-88784-598-7 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $14.95 WINTER 2014 978-0-88784-843-8 978-0-88784-895-7 978-1-77089-225-5 978-0-88784-881-0 ANANSI PUBLISHES VERY GOOD BOOKS WWW.HOUSEOFANANSI.COM Anansi_F13_cover.indd 1-2 13-05-15 11:51 AM HOUSE OF ANANSI FALL 2013 / WINTER 2014 TITLES SCOTT GRIFFIN Chair NONFICTION ... 1 SARAH MACLACHLAN President & Publisher FICTION ... 17 ALLAN IBARRA VP Finance ASTORIA (SHORT FICTION) ... 23 MATT WILLIAMS VP Publishing Operations ARACHNIDE (FRENCH TRANSLATION) ... 29 JANIE YOON Senior Editor, Nonfiction ANANSI INTERNATIONAL ... 35 JANICE ZAWERBNY Senior Editor, Canadian Fiction SPIDERLINE .. -

Dictionaries Were, However, Better – and Were Relentlessly Promoted in Canada’S Middlebrow Media by Their Editor, the Jolly Mediævalist Katherine Barber

The right reason to write a book Anger. Or is that the wrong reason? Either way, it is what drove me to write Organizing Our Marvellous Neighbours. But let me start out with a bit of personal history. I was always a good speller. On the only occasion I lost a spelling bee in grade school, the word that did me in was beau, ironically enough. One year, we had a weekly writing lesson in which I sat at the front of the class spelling words on demand for my fellow students. Thirty years have passed, but I still notice spelling. I notice spelling mistakes. Those aren’t always important (perfect spelling in your chat window does not make your instant messages perfect), but spelling mistakes, punctuation errors, and the like will jump right out at me. They’re often the first thing I notice when I look at a page – a phenomenon that carried through to the publication of my first book, where I noticed the mistakes before anything else. But I’ve noticed other things beyond misspellings. I noticed across-the- board American spellings in Canadian publications – and, much more often, all- British spellings. I noticed those things, but that’s all I did. The year 2002 would be a turning point. I’d been watching TV captioning for 30 years, but it was in 2002 that CBC agreed to closed-caption 100% of its programming on two networks, CBC Television and Newsworld. That came about as the result of a human-rights complaint that CBC had lost. -

Women Writing Translation in Canada Les Actes De Passage : Les Femmes Et « L’Écriture Comme Traduction » Au Canada Alessandra Capperdoni

Document generated on 10/01/2021 3:41 a.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, rédaction Acts of Passage: Women Writing Translation in Canada Les actes de passage : les femmes et « l’écriture comme traduction » au Canada Alessandra Capperdoni TTR a 20 ans I Article abstract TTR Turns 20 I This article discusses the relationship of writing and translation in Canadian Volume 20, Number 1, 1er semestre 2007 feminist poetics, specifically experimental. As feminist poetics collapsing the boundaries between theory and creative act, “writing as translation” is a mode URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018505ar of articulation for female subjectivity and a strategy for oppositional poetics. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/018505ar The article engages with the practice of “writing as translation” in the works of two leading avant-garde artists, the francophone Nicole Brossard and the anglophone Daphne Marlatt, located respectively in Montreal and Vancouver. See table of contents Building on the groundbreaking critical work of Barbara Godard, Kathy Mezei and Sherry Simon, it situates these practices in the socio-political and intellectual context of the 1970s and 1980s, which witnessed the emergence of Publisher(s) women’s movements, feminist communities and feminist criticism, and in relation to the politics of translation in Canada. This historicization is Association canadienne de traductologie necessary not only to understand the innovative work of Canadian feminist poetics but also the political dissemination of a feminist culture bringing ISSN together English and French Canada. 0835-8443 (print) 1708-2188 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Capperdoni, A. (2007). Acts of Passage: Women Writing Translation in Canada. -

150 Canadian Books to Read

150 CANADIAN BOOKS TO READ Books for Adults (Fiction) 419 by Will Ferguson Generation X by Douglas Coupland A Better Man by Leah McLaren The Girl who was Saturday Night by Heather A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews O’Neill A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Across The Bridge by Mavis Gallant Helpless by Barbara Gowdy Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Home from the Vinyl Café by Stuart McLean All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese And The Birds Rained Down by Jocelyne Saucier The Island Walkers by John Bemrose Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje The Jade Peony by Wayson Choy Annabel by Kathleen Winter jPod by Douglas Coupland As For Me and My House by Sinclair Ross Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay The Back of the Turtle by Thomas King Lives of the Saints by Nino Ricci Barney’s Version by Mordecai Richler Love and Other Chemical Imbalances by Adam Beatrice & Virgil by Yann Martel Clark Beautiful Losers by Leonard Cohen Luck by Joan Barfoot The Best Kind of People by Zoe Whittall Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese The Best Laid Plans by Terry Fallis Mercy Among The Children by David Adams The Birth House by Ami McKay Richards The Bishop’s Man by Linden MacIntyre No Great Mischief by Alistair Macleod Black Robe by Brian Moore The Other Side of the Bridge by Mary Lawson Blackfly Season by Giles Blunt The Outlander by Gil Adamson The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill The Piano Man’s Daughter by Timothy Findley The Break by Katherena Vermette The Polished Hoe by Austin Clarke The Cat’s Table by Michael Ondaatje Quantum Night by Robert J. -

Book Club Kit Discussion Guide Handmaid's Tale by Margaret

Book Club Kit Discussion Guide Handmaid’s Tale By Margaret Atwood Author: Margaret Atwood was born in 1939 in Ottawa, and grew up in northern Ontario and Quebec, and in Toronto. She received her undergraduate degree from Victoria College at the University of Toronto and her master’s degree from Radcliffe College. Margaret Atwood is the author of more than forty books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays. Her latest book of short stories is Stone Mattress: Nine Tales (2014). Her MaddAddam trilogy – the Giller and Booker prize- nominated Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009), and MaddAddam (2013) – is currently being adapted for HBO. The Door is her latest volume of poetry (2007). Her most recent non-fiction books are Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth (2008) and In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination (2011). Her novels include The Blind Assassin, winner of the Booker Prize; Alias Grace, which won the Giller Prize in Canada and the Premio Mondello in Italy; and The Robber Bride, Cat’s Eye, The Handmaid’s Tale – coming soon as a TV series with MGM and Hulu – and The Penelopiad. Her new novel, The Heart Goes Last, was published in September 2015. Forthcoming in 2016 are Hag-Seed, a novel revisitation of Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, for the Hogarth Shakespeare Project, and Angel Catbird – with a cat-bird superhero – a graphic novel with co-creator Johnnie Christmas. (Dark Horse.) Margaret Atwood lives in Toronto with writer Graeme Gibson. (From author’s website.) Summary: In the world of the near future, who will control women's bodies? Offred is a Handmaid in the Republic of Gilead.