Implications of Hydroelectric Partnerships in Northern Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race Rocks (Xwayen) Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisher

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report Nicole Backe, Sarah Davies, Kevin Conley, Gabrielle Kosmider, Glen Rasmussen, Hilary Ibey, Kate Ladell Ecosystem Management Branch Pacific Region - Oceans Sector Fisheries and Oceans Canada, South Coast 1965 Island Diesel Way Nanaimo, British Columbia V9S 5W8 Marine Ecosystems and Aquaculture Division Fisheries and Oceans Canada Pacific Biological Station 3190 Hammond Bay Road Nanaimo, British Columbia V9T 6N7 2011 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2949 ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs 97-13/2949E ISSN 1488-5387 Correct citation for this publication: Backe, N., S. Davies, K. Conley, G. Kosmider, G. Rasmussen, H. Ibey and K. Ladell. 2011. Race rocks (XwaYeN) proposed marine protected area ecosystem overview and assessment report. Can. Manuscr. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2949: ii + 30 p. Executive Summary Background Race Rocks (XwaYeN), located 17 km southwest of Victoria in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, consists of nine islets, including the large main island, Great Race. Named for its strong tidal currents and rocky reefs, the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are a showcase for Pacific marine life. This marine life is the result of oceanographic conditions supplying the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area with a generous stream of nutrients and high levels of dissolved oxygen. These factors contribute to the creation of an ecosystem of high biodiversity and biological productivity. In 1980, the province of British Columbia, under the authority of the provincial Ecological Reserves Act, established the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. This provided protection of the terrestrial natural and cultural heritage values (nine islets) and of the ocean seabed (to the 20 fathoms/36.6 meter contour line). -

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

3. Strait of Juan De Fuca Ecosystem: Marine Shorelines

Clallam County SMP Update - Inventory and Characterization Report 3. STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA ECOSYSTEM: MARINE SHORELINES Clallam County marine shorelines are buffeted directly by wind and waves entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca from the Pacific Ocean. The shoreline is shaped by seasonal shifts in weather along with cycles of ocean temperature and long term climate change. The underlying geology of the Olympic Peninsula also affects the shape and character of the shoreline through erosion, landslides, sediment movement and beach formation. The protected coves, bays and river mouths along the Strait of Juan de Fuca have been the sites for human settlements for thousands of years. More recently, the weather and spectacular views of wildlife have attracted development along exposed bluffs and beaches. What happens along the marine shoreline—through natural or human-generated activities—affects the people who live along the shorelines as well as resource-based businesses and the many species that depend on the nearshore for food, cover from predators migrating to the ocean. The Strait of Juan de Fuca provides habitat and migration corridors for many species of Puget Sound and Fraser River salmon, marine mammals and thousands of migratory birds, including many State-identified “priority species” (Table 3-1). The nearshore ecosystem supports aquatic plants and animals that feed the upper levels of the food web. Table 3-1. Priority wildlife species mapped along the Clallam County, Strait of Juan de Fuca shorelines (Sources: WDFW, WDNR) Terrestrial -

Pimicikamak Okimawin Onasowewin the First Written Law Page 2

!"#"$"%&#&%'(%"#&)"*'(*&+,)-)"*'.'/'01-2'3,)&45+'6-$,7,*"8&1",*9' ' ' :;! ' ' <-*5;'=&-'=,++' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' /'3>-+"+'+?:#"11-5'1,'1>-'@&$?71;',A'B4&5?&1-'01?5"-+',A' ' 3>-'C*"D-4+"1;',A'E&*"1,:&' ' "*'2&41"&7'A?7A"7#-*1',A'1>-'4-F?"4-#-*1+',A'1>-'5-G4--',A' ' ' ' ' ' E/03H='(@'/=30' ' ' ' ' 6-2&41#-*1',A'I&1"D-'01?5"-+' ' C*"D-4+"1;',A'E&*"1,:&' ' <"**"2-G' ' ' ' ' ' ' "#$%&'()*!J!+,-,!.%!/012%!3#44' 56.70!#8!"#1*01*4! /:+14&$1' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' L' /$%*,)7-5G-#-*1+' '' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' M' 6-5"$&1",*'N'E-#,4"&#' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' O' ' P>&21-4'(*-Q'R*14,5?$1",*' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' S' ' 3>-'T?-+1",*U'1>-'T?&G#"4-' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' VK' ' !,+"1",*',A'1>-'=-+-&4$>-4'.'<>-4-'R'$,#-'A4,#' ' ' ' ' VM' ' <4"1"*G'W&$%' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' VX' ' 3>-'=&1",*&7-' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' VS' ' 6&1&'P,77-$1",*'.'3>-'!4,$-++'1>-'E-1>,5' ' ' ' ' ' KY' ' 3>-+"+'W4-&%5,)*' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ZY' P>&21-4'3),Q'!"#"$"%&#&%Q'3>-'[,$&1",*'<>-4-'E;'6&5'$,#-+'A4,#' ' ' ZV' ' E&*"1,:&'\;54,]'3>-'@7,,5]'3>-'I,41>-4*'@7,,5'/G4--#-*1'^I@/_' ' &*5'/++-41"*G'0,D-4-"G*1;' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' LZ' ' 3>-'I,41>-4*'@7,,5'/G4--#-*1'^I@/_' ' ' ' ' ' LS' ' ' 3>-'@"4+1'<4"11-*'[&)'.'(%"#&)"*'(*&+,)-)"*' ' ' ' ' MZ' ' \;54,'!&;#-*1'[&)' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' MO' ' P"1"8-*+>"2'[&)' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' MS' ' H7-$1",*'[&)' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' M`' ' P,*$7?+",*+' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' XV' P>&21-4'3>4--Q'P,#27-a"1"-+'"*'6-$,7,*"8&1",*' ' ' ' ' ' XZ' ' P,*$7?+",*+' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' SV' K P>&21-4'@,?4Q'/$>"-D"*G'#"*,b2"#&1"+")"*' ' ' ' ' ' ' SZ' ' R#2,41&*$-',A'P4--'[&*G?&G-' ' ' ' ' ' ' SM' ' R#2,41&*$-',A'H5?$&1",*'&*5'/$F?"4"*G'c*,)7-5G-' -

Securing the Border: Understanding the Threats and Strategies for the Northern Border”

Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area 300 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1300 Seattle, WA 98104 (206) 352-3600 fax (206) 352-3699 Prepared for the Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs “Securing the Border: Understanding the Threats and Strategies for the Northern Border” Testimony of Dave Rodriguez Director, Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) April 22, 2015 Chairman Johnson, distinguished members of this committee, my name is Dave Rodriguez and I have been the director of the Northwest HIDTA since June 1997. I first would like to thank the committee for its attention to exploring the national security threats facing our northern border. Additionally I wish to thank you for this opportunity for input from the Northwest HIDTA Program. The Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) incorporates 14 counties located on both the east and west sides of the Cascade Mountains. The western counties extend from the United States (US)-Canada border south to the Oregon border and include Clark, Cowlitz, King, Kitsap, Lewis, Pierce, Skagit, Snohomish, Thurston, and Whatcom County. The Eastern Washington counties include Benton, Franklin, Spokane, and Yakima. Within these vastly divergent jurisdictions, the Northwest HIDTA facilitates cooperation and joint efforts among more than 115 international, federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies. The Northwest HIDTA works with these agencies to identify drug threats and implement the strategies necessary to address them. Washington’s topography and location render it conducive to drug smuggling and production. The Washington section of the US-Canada border is approximately 430 miles in length, with 13 official ports of entry (POE). -

TARDIVEL-THESIS-2019.Pdf (1.146Mb)

NAVIGATING INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP IN A SETTLER COLONIAL WORLD: RON AND PATRICIA JOHN ‘COME HOME’ TO STÓ:LÕ POLITICS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN SASKATOON By Angélique Tardivel © Copyright Angélique Tardivel, April 2019. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Reference in this thesis to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the University of Saskatchewan. The views and opinions of the author do not state or reflect those of the University of Saskatchewan, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

Waters of the United States in Washington with Green Sturgeon Identified As NMFS Listed Resource of Concern for EPA's PGP

Waters of the United States in Washington with Green Sturgeon identified as NMFS Listed Resource of Concern for EPA's PGP (1) Coastal marine areas: All U.S. coastal marine waters out to the 60 fm depth bathymetry line (relative to MLLW) from Monterey Bay, California (36°38′12″ N./121°56′13″ W.) north and east to include waters in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Washington. The Strait of Juan de Fuca includes all U.S. marine waters: Clallam County east of a line connecting Cape Flattery (48°23′10″ N./ 124°43′32″ W.) Tatoosh Island (48°23′30″ N./124°44′12″ W.) and Bonilla Point, British Columbia (48°35′30″ N./124°43′00″ W.) Jefferson and Island counties north and west of a line connecting Point Wilson (48°08′38″ N./122°45′07″ W.) and Partridge Point (48°13′29″ N./122°46′11″ W.) San Juan and Skagit counties south of lines connecting the U.S.-Canada border (48°27′27″ N./ 123°09′46″ W.) and Pile Point (48°28′56″ N./123°05′33″ W.), Cattle Point (48°27′1″ N./122°57′39″ W.) and Davis Point (48°27′21″ N./122°56′03″ W.), and Fidalgo Head (48°29′34″ N./122°42′07″ W.) and Lopez Island (48°28′43″ N./ 122°49′08″ W.) (2) Coastal bays and estuaries: Critical habitat is designated to include the following coastal bays and estuaries in California, Oregon, and Washington: (vii) Lower Columbia River estuary, Washington and Oregon. All tidally influenced areas of the lower Columbia River estuary from the mouth upstream to river kilometer 74, up to the elevation of mean higher high water, including, but not limited to, areas upstream to the head of tide endpoint -

Chapter 11. Juan De Fuca Strait

Chapter 11. Juan de Fuca Strait - Physiography channels lead into Haro Strait. The lesser channels lead into Rosario Strait, Admiralty Inlet, and Deception Pas- Juan de Fuca Strait is a long, narrow submarine valley sage. For the most part, depths within Juan de Fuca Strait that originates along a depression bchvccn the resistant are appreciably less than those in the Strait of Georgia. lava flows and metamorphic rocks of southern Vancouver The coastline of the Strait is relatively uniform with a Island and thc Olympic Mountains (Fig. 11.1).Over the low rocky shoreline abutted against cliffs to 20 m high. last 1-2 million yr, the Strait has undergone excavation on Centuries of wave action have turned much of the shore at least four separate occasions, as continental ice sheets into rocky intertidal platforms that are often engulfed in moved seaward during periods of worldwide cooling. kelp in summer. Though sandy sediments are scarce due to East of the line bcnvccn Jordan River and Pillar the weather-resistant nature of the r, xks, numerous small Point, the region is characterized by a gcntly sloping U- beaches have developed which, in -he eastern portion, shapcd, cross-channel profile linked to recent glacial pro- consist mainly of pebble-cobble matiarid with logs at the cesses. A large terminal moraine, the Victoria-Green head of the beaches. In the western section there are many Point sill, marks the furthest point of advance of an an- small pocket beaches of coarse sediments and a few nar- cient ice sheet that once existed in the Strait. -

SEATTLE 5, WASHINGTON Universll~ of WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT of OCEANOGRAPHY (Formerly Oceanographic Laboratories) Seattle, Washington

I ~: .~:::::::iii~:i:::~\' SEATTLE 5, WASHINGTON UNIVERSll~ OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF OCEANOGRAPHY (Formerly Oceanographic Laboratories) Seattle, Washington ',' THE SURFACE WINDS OVER PUGET SOUND AND THE STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA AND THEIR OCEANOGRAPHIC EFFECTS by Russell G. Harris and .v10e Rattray Jr. Technical Report No. 37 Office of Naval Research Contract N8onr-520/II1 Project NR 083 012 '~~.r<~,_ ~ ~ R~f6rence 54-27 .. 11';Cl July 1954 ichard H. Fleming ~ ecutive Officer ABSTRACT The surface winds which occur over the waters of Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca present a complex picture. Strongly affected by topography, they cannot be predicted or fully explained solely by consideration of the changing atmospheric pressure patterns over or near the region. A detailed summary of accumulated surface wind reports is de- sirable, therefore, to satisfy the increasing demand for a reasonably accurate climatic picture of the surface flow over this region througll- out the year. In particular, oceanographic and fishery investiga- ~ions being conducted in these waters have shown the need for more detailed and comprehensive information of this sort than is presently available. This report attempts to partially satisfy this need in two ways. First, all available wind report summaries have been accumu- lated in the form of monthly wind roses for each reporting station. Secondly, a determination has been made of the frequency and maximum duration of surface winds of above average velocity at selected sta- tions over a three year period. Particular meteorological situations have been selected and discussed, to serve as examples of the general or unusual flow pat- terns derived from the summarized data. -

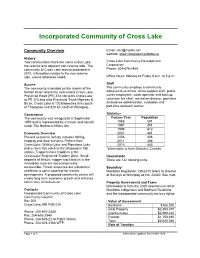

Incorporated Community of Cross Lake

Incorporated Community of Cross Lake Community Overview Email: [email protected] website: www.crosslakemanitoba.ca History Two communities share the name Cross Lake, Cross Lake Community Development the reserve and adjacent non-reserve side. The Corporation community of Cross Lake was incorporated in Phone: 204-676-2465 2010. Information relates to the non-reserve side, unless otherwise noted. Office hours: Monday to Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Access Staff The community is located on the shores of the The community employs a community Nelson River where the river enters Cross Lake. administrative officer, office support staff, public Provincial Road (PR) 374 connects Cross Lake works employees, water operator and backup, to PR 373 and onto Provincial Trunk Highway 6. volunteer fire chief, recreation director, part-time By air, Cross Lake is 120 kilometres (km) south ambulance administrator, custodian and of Thompson and 520 km north of Winnipeg. part-time outreach worker. Governance Statistics The community was recognized in September Census Year Population 1970 and is represented by a mayor and council 1985 581 under The Northern Affairs Act. 1991 401 1996 412 Economic Overview 2001 481 Present economic activity includes fishing, 2006 406 trapping and local services. Fishers from 2011 388 Cross Lake, Walker Lake and Pipestone Lake 2016 443 deliver their fish catch to the Wabowden fish *information is from Statistics Canada station. Trappers have traplines in the Cross Lake Registered Trapline Zone. Small Households deposits of lithium, copper and titanium in the There are 142 housing units. immediate area are not economically recoverable. Forest resources are substantial Boundary and there is some potential for market Manitoba Regulation 135/2010 refers to Director development. -

Response Capability Analysis for U.S. and Canadian Shared Waters Report to Congress May 29, 2014

Response Capability Analysis for U.S. and Canadian Shared Waters Report to Congress May 29, 2014 This page was intentionally left blank Foreword I am pleased to present the following report, “Response Capability Analysis for U.S. and Canadian Shared Waters,” which has been prepared by the U.S. Coast Guard. The Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010 (Pub. L. 111-281), Section 711(a), directs the Commandant to submit recommendations based on updates to the comparability analysis which serves as the basis for the Cooperative Vessel Traffic Service agreement between the United States and Canada for the management of maritime traffic in Puget Sound, the Strait of Georgia, Haro Strait, Rosario Strait, and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Pursuant to Congressional requirements, this report is being provided to the following members of Congress: The Honorable Bill Shuster Chairman, House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure The Honorable Nick J. Rahall II Ranking Member, House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure The Honorable John D. Rockefeller IV Chairman, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation The Honorable John Thune Ranking Member, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. I am happy to answer any further questions you may have, or your staff may contact my Senate Liaison Office at (202) 224-2913 or House Liaison Office at (202) 225-4775. Sincerely, U. S. Coast Guard i Table of Contents I. Legislative Language 1 II. Background 2 III. Report 4 ii I. Legislative Language This report responds to the language set forth in Section 711(a) of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010 (Pub.