Change and Continuity in the Financing of the 2016 U.S. Federal Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

Brief for Southeastern Legal Foundation, Inc., As

Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10405035, DktEntry: 127, Page 1 of 36 Docket No. 17-15589 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Ninth Circuit STATE OF HAWAII and ISMAIL ELSHIKH, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, JOHN F. KELLY, in his official capacity as Secretary of Homeland Security, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, REX W. TILLERSON, in his official capacity as Secretary of State and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendants-Appellants. _______________________________________ Appeal from a Decision of the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii, No. 1:17-cv-00050-DKW-KSC ∙ Honorable Derrick Kahala Watson BRIEF FOR SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDATION, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS AND REVERSAL Kimberly S. Hermann William S. Consovoy SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDATION CONSOVOY MCCARTHY PARK PLLC 2255 Sewell Mill Road, Suite 320 3033 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 700 Marietta, Georgia 30062 Arlington, Virginia 22201 (770) 977-2131 (703) 243-9423 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae Southeastern Legal Foundation COUNSEL PRESS ∙ (800) 3-APPEAL PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10405035, DktEntry: 127, Page 2 of 36 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Southeastern Legal Foundation has no parent company, and no publicly held company owns 10% or more of its stock. i Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10405035, DktEntry: 127, Page 3 of 36 TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT .......................................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... iii IDENTITY & INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ................................................. -

Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Talk “Like a Man”: Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Political Science by Jennifer J. Jones Dissertation Committee: Professor Kristen Monroe, Chair Professor Marty Wattenberg Professor Michael Tesler 2017 Chapter 4 c 2016 American Political Science Association and Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission. All other materials c 2017 Jennifer J. Jones TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review 5 2.1 Social Identity and Its Effect on Social Cognition . 6 2.1.1 Stereotypes and Expectations . 9 2.1.2 Conceptualizing Gender in US Politics . 13 2.2 Gender and Self-Presentation in US Politics . 16 2.2.1 Masculine Norms of Interaction in Institutional Settings . 16 2.2.2 Political Stereotypes and Leadership Prototypes . 18 2.3 The Impact of Political Communication in Electoral Politics . 22 2.4 Do Women Have to Talk Like Men to Be Considered Viable Leaders? . 27 3 Methods: Words are Data 29 3.1 Approaches to Studying Language . 30 3.2 Analyzing Linguistic Style . 34 3.2.1 Gendered Communication and the Feminine/Masculine Ratio . 37 3.2.2 Comparison with Other Coding Schemes . 39 3.3 Approaches to Studying Social Perception and Attitudes . 40 3.3.1 The Link Between Linguistic Style and Implicit Associations . 42 4 The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013 45 4.1 The Case of Hillary Clinton . -

Federal Election Commission 1 2 First General Counsel's

MUR759900019 1 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 3 FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL’S REPORT 4 5 MUR 7304 6 DATE COMPLAINT FILED: December 15, 2017 7 DATE OF NOTIFICATIONS: December 21, 2017 8 DATE LAST RESPONSE RECEIVED September 4, 2018 9 DATE ACTIVATED: May 3, 2018 10 11 EARLIEST SOL: September 10, 2020 12 LATEST SOL: December 31, 2021 13 ELECTION CYCLE: 2016 14 15 COMPLAINANT: Committee to Defend the President 16 17 RESPONDENTS: Hillary Victory Fund and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 18 treasurer 19 Hillary Rodham Clinton 20 Hillary for America and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 21 treasurer 22 DNC Services Corporation/Democratic National Committee and 23 William Q. Derrough in his official capacity as treasurer 24 Alaska Democratic Party and Carolyn Covington in her official 25 capacity as treasurer 26 Democratic Party of Arkansas and Dawne Vandiver in her official 27 capacity as treasurer 28 Colorado Democratic Party and Rita Simas in her official capacity 29 as treasurer 30 Democratic State Committee (Delaware) and Helene Keeley in her 31 official capacity as treasurer 32 Democratic Executive Committee of Florida and Francesca Menes 33 in her official capacity as treasurer 34 Georgia Federal Elections Committee and Kip Carr in his official 35 capacity as treasurer 36 Idaho State Democratic Party and Leroy Hayes in his official 37 capacity as treasurer 38 Indiana Democratic Congressional Victory Committee and Henry 39 Fernandez in his official capacity as treasurer 40 Iowa Democratic Party and Ken Sagar in his official capacity as 41 treasurer 42 Kansas Democratic Party and Bill Hutton in his official capacity as 43 treasurer 44 Kentucky State Democratic Central Executive Committee and M. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Look to the Governors— Federalism Still Lives by Karlyn H

Chapter 4 Table 1: House Vote, By Income Group 1994 1996 1998 D R D R D R Less than $15,000 60% 37% 61% 36% 57% 39% $15,000-$30,000 50 48 54 43 53 44 $30,000-$50,000 44 54 49 49 48 49 $50,000-$75,000 45 54 47 52 44 54 $75,000+ 38 61 39 59 45 52 Source: Surveys by Voter News Service. tion, health care, Social Security. The effect was predictable: or more is growing rapidly and can’t be taken for granted a significant shift in support from Republican candidates to anymore. The GOP must decide what issues will allow it to Democratic ones. That result creates a dilemma for the GOP hold onto the gains made among non-affluent voters while not as it looks ahead to the next House elections. On the one hand, losing any more ground with the affluent. whatever the causes for the GOP’s loss of support among the affluent, those same causes apparently helped Republicans The extent to which the Republicans are successful, and gain enough ground with non-affluent voters to hold onto a the extent to which the Democrats can thwart their strategy, House majority. But the voter bloc of those making $75,000 could determine who controls the House in 2000. Look to the Governors— Federalism Still Lives By Karlyn H. Bowman In his 1988 book, Laboratories of Democracy, political Eight of the country’s ten most populous states have Republi- writer David Osborne urged readers to look beyond Washing- can governors. -

Virginia's Kaine Has Big Early Lead In

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: FEBRUARY 17, 2017 VIRGINIA’S KAINE HAS BIG EARLY LEAD IN SENATE RACE, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; TRUMP DEEP IN A JOB APPROVAL HOLE Two well-known Republican women who might challenge Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine for reelection in 2018 get no help from their sisters, as Kaine leads among women by 23 percentage points in either race, leaving him with a comfortable overall lead, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. Sen. Kaine leads Republican talk show host Laura Ingraham 56 – 36 percent among all voters and tops businesswoman Carly Fiorina 57 – 36 percent, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds. In the Kaine-Ingraham matchup, the Democrat leads 57 – 34 percent among women and 54 – 39 percent among men. He takes Democrats 98 – 1 percent and independent voters 54 – 32 percent. Republicans back Ingraham 86 – 8 percent. White voters are divided with 48 percent for Kaine and 45 percent for Ingraham. Non- white voters go to Kaine 74 – 15 percent. Kaine leads Fiorina 57 – 34 percent among women and 56 – 39 percent among men, 98 – 1 percent among Democrats and 55 – 32 percent among independent voters. Republicans back Fiorina 86 – 8 percent. He gets 49 percent of white voters to 45 percent for Fiorina. Non- white voters back Kaine 75 – 16 percent. “There is a certain similarity to how Virginia voters see Republican officials and potential GOP candidates these days. As was evident in the Quinnipiac University poll earlier this week that showed the Democratic candidates for governor were running better than their Republican counterparts, the same pattern holds true for President Donald Trump's job approval and for an early look at Sen. -

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Www. George Wbush.Com

Post Office Box 10648 Arlington, VA 2221 0 Phone. 703-647-2700 Fax: 703-647-2993 www. George WBush.com October 27,2004 , . a VIA FACSIMILE (202-219-3923) AND CERTIFIED MAIL == c3 F Federal Election Commission 999 E Street NW Washington, DC 20463 b ATTN: Office of General Counsel e r\, Re: MUR3525 Dear Federal Election Commission: On behalf of President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard B. Cheney as candidates for federal office, Karl Rove, David Herndon and Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc., this letter responds to the allegations contained in the complaint filed with the Federal Election Commission (the “Commission”) by Kerry-Edwards 2004, Inc. The Kerry Campaign’s complaint alleges that Bush-Cheney 2004 and fourteen other individuals and organizations violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 197 1, as amended (2 U.S.C. $ 431 et seq.) (“the Act”). Specifically, the Kerry Campaign alleges that individuals and organizations named in the complaint illegally coordinated with one another to produce and air advertising about Senator. Kerry’s military service. 1 Considering that no entity by the name of Bush-Cheney 2004 appears to exist, 1’ Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc. (“Bush Campaign”) presumes that the Kerry Campaign mistakenly filed its complaint against a non-existent entity and actually intended to file against the Bush Campaign. Assuming that the foregoing presumption is correct; the Bush Campaign, on behalf of itself and President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. Cheney, Karl Rove, David Herndon (the “Parties”), responds as follows: Response to Allegations Against President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. -

Rejected Write-Ins

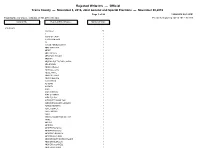

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Hillary Clinton's Campaign Was Undone by a Clash of Personalities

64 Hillary Clinton’s campaign was undone by a clash of personalities more toxic than anyone imagined. E-mails and memos— published here for the first time—reveal the backstabbing and conflicting strategies that produced an epic meltdown. BY JOSHUA GREEN The Front-Runner’s Fall or all that has been written and said about Hillary Clin- e-mail feuds was handed over. (See for yourself: much of it is ton’s epic collapse in the Democratic primaries, one posted online at www.theatlantic.com/clinton.) Fissue still nags. Everybody knows what happened. But Two things struck me right away. The first was that, outward we still don’t have a clear picture of how it happened, or why. appearances notwithstanding, the campaign prepared a clear The after-battle assessments in the major newspapers and strategy and did considerable planning. It sweated the large newsweeklies generally agreed on the big picture: the cam- themes (Clinton’s late-in-the-game emergence as a blue-collar paign was not prepared for a lengthy fight; it had an insuf- champion had been the idea all along) and the small details ficient delegate operation; it squandered vast sums of money; (campaign staffers in Portland, Oregon, kept tabs on Monica and the candidate herself evinced a paralyzing schizophrenia— Lewinsky, who lived there, to avoid any surprise encounters). one day a shots-’n’-beers brawler, the next a Hallmark Channel The second was the thought: Wow, it was even worse than I’d mom. Through it all, her staff feuded and bickered, while her imagined! The anger and toxic obsessions overwhelmed even husband distracted. -

Strategic Communications Workshop

WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM Overview Strategic Communications Workshop Market Research Analysis NASA Message Architecture Outreach Strategies New Message Platform Next Steps 3 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM 4 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM The Office of Communications Planning (OCP) is charged with developing long-term communication strategies and plans for increasing public awareness and understanding of NASA’s mission and goals. 5 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM What is a Strategic Communications Framework? A Guide to implement Strategic Communications • It is a document which includes message architecture, target audiences, new outreach mechanisms, and strategies for implementation. • It can be used to build support throughout the Agency for Strategic Communications plans and activities. • It is an actionable document that evolves. A Strategic Communications Framework Guides the Agency’s Communications 6 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM Purpose • You are here today for the presentation of the NASA Strategic Communications Framework. • We are requesting your inputs by Monday, November 27, 2006. Together, we embark on a new Communications Approach for the Agency. Today is the first step. 7 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM Process Strategic Market Research Communications Analysis Workshop Formulation Validation Rollout Testing 8 WWW.NASAWATCH.COM WWW.NASAWATCH.COM Schedule ACTIVITY OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB DEVELOP FRAMEWORK FORMULATION PHASE 11-13 STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS WORKSHOP MARKET RESEARCH