Highlighted Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qatar Travel Guide

Qatar Travel Guide Zubarah fort, Qatar Qatar was previously a poor country. But with the help of oil and gas fields, the country has made a rapid economic progress. Initially, Qatar did not issue visas for the tourists. From 1989 onwards, they have started issuing them. The land of sand dunes, brilliant architecture, wonderful hotels, and rock carvings is now open to outsiders. Qatar is divided into nine municipalities namely Ad Dawhah, Al Khawr, Al Ghuwayriyah, Jarayan al Batinah, Madinat ash Shamal, Al Jumayliyah, Al Wakrah, Umm Salal, and Ar Rayyan. The official language of Qatar is Arabic. English is also widely spoken in Qatar. The capital city of Qatar is Doha. When you reach Qatar by plane, you are likely to land in Doha. The Qatar airways are the major airlines of Qatar. You can reach Qatar by car or bus from Saudi Arabia. Taxis, buses, and limousines will facilitate intra-country traveling. During the summer months the heat is unbearable. November and February offer pleasant weather for the tourists and are the months, when you should be looking to travel to Qatar. Some of the major tourist attractions in Qatar are: Qatar National Museum and Aquarium, Doha The Corniche, Doha City Center Mall, Doha Doha Ethnographic Museum Doha Fort Al Shaqab Stud farm Zubara Fort Doha Golf Club Getting In Qatar attracts travelers with its unique beauty and host of other attractions. Reaching Qatar by air is quite a convenient option because of the presence of an international airport in Doha. Here, the Qatar Airways has established a worldwide network. -

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012 Quality of Service REPORT Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 The purpose of the study is to evaluate and benchmark Quality Levels offered by Mobile Network Operators, Qtel and Vodafone, in the state of Qatar. The independent study was conducted with an objective End-user perspective by Directique and does not represent any views of ictQATAR. This study is the property of ictQATAR. Any effort to use this Study for any purpose is permitted only upon ictQATAR’s written consent. 2 Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 READER’S ADVICE ........................................................................................ 4 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 TEAM AND EQUIPMENT ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 VOICE SERVICE QUALITY TESTING ...................................................................... 6 2.3 SMS, MMS AND BBM MEASUREMENTS ............................................................ 14 2.4 DATA SERVICE TESTING ................................................................................... 16 2.5 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................... 23 3 INDUSTRY RESULTS AND INTERNATIONAL BENCHMARK ........................... 25 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Ceramics from Islamic Lands (Victoria and Albert Museum) - 19-23 July

H-Islamart CORRECTION: Online Conference - Ceramics from Islamic Lands (Victoria and Albert Museum) - 19-23 July Discussion published by Ashley Dimmig on Monday, June 21, 2021 Submitted by Mariam Rosser-Owen: Dear colleagues, CERAMICS FROM ISLAMIC LANDS CONFERENCE Hosted by the Victoria and Albert Museum - taking place online! 19-23 JULY *CORRECT LINK: https://www.vam.ac.uk/event/ZXZZjyXo/islamic-ceramics-online-conference-july-202 1 Please join us online in a month's time to discuss all things ceramic, from archaeology to contemporary practice! The conference programme is copied below, and you can also download it from our registration page. The conference is free to attend. Conference papers will be available to view to conference attendees from two weeks before and two weeks after the conference. The conference will then take the form of live online panel discussions, in the mornings and afternoons of 20th-23rd July, with the keynote lecture a live event on the evening of 19th July. All times are in BST. Please help us to spread the word by circulating this link to your networks, colleagues and students! If you have any queries, please send us an email at: [email protected]. We look forward to seeing you virtually at the V&A in a month's time! Provisional programme: Citation: Ashley Dimmig. CORRECTION: Online Conference - Ceramics from Islamic Lands (Victoria and Albert Museum) - 19-23 July. H-Islamart. 06-21-2021. https://networks.h-net.org/node/7636/discussions/7860124/correction-online-conference-ceramics-islamic-lands-victoria-and Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. -

List of Approved Ships for the Zeebrugge Lng Terminal

LIST OF APPROVED SHIPS FOR THE ZEEBRUGGE LNG TERMINAL (*) Daylight restriction not applicable if a sister vessel has called the Terminal before Next berhting only VESSEL Jetty 1 (EAST) Jetty 2 (WEST) under daylight conditions (*) Aamira Approved Adriano Knutsen Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Aamriya Approved Approved Al Areesh Approved Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Al Bahiya Approved Approved Al Bidda Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Dafna Approved Al Deebel Approved Al Gattara Approved Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Al Ghariya Approved Al Gharrafa Approved Approved Al Ghashamiya Approved Approved Al Hamla Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Huwaila Approved Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Al Jasra Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Karaana Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Approved Al Kharaitiyat Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Approved Al Khattiya Approved Approved Al Khor Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Khuwair Approved Approved Al Mayeda Approved Al Nuaman Approved Approved Al Oraiq Approved Approved Al Rayyan Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Ship-shore Interface Study Completed YES Al Ruwais Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Approved Al Sadd Ship-shore Interface Study Completed Approved Al Safliya Approved Al Sahla Approved Approved Al Shamal Approved Ship-shore Interface -

Keeping History Alive – Guide to Heritage Sites in Qatar Taking Qm Beyond the Walls Taking Qm Beyond the Walls – – Introduction Content

KEEPING HISTORY ALIVE – GUIDE TO HERITAGE SITES IN QATAR TAKING QM BEYOND THE WALLS TAKING QM BEYOND THE WALLS – – INTRODUCTION CONTENT From Bronze age settlements to medieval palaces, 19th century forts, villages, Heritage SITES Location MAP 7 towers and mosques, the Qatar Museums team excavates, restores, protects and promotes heritage sites of Qatar that flourished long ago. We put local communities, Archaeological Heritage 9 young and old, in touch with their past, reminding them of the skills, wisdom and the AL ZubaRAH ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE 10 struggles of their ancestors. FREIHA 16 RuwaYda 18 Our goals are to dig into the past and discover its traces, to protect heritage sites and safeguard them for future generations, and to develop them in order to attract MURwab 20 visitors and educate them about Qatar’s rich culture and history. Architectural Heritage 23 BARZAN TowERS 24 AL KHOR TowERS 28 THE WELL OF AIN HLEEtaN 30 OLD PALacE IN DOHA 32 AL REKAYat FORT 36 AL THAGHAB FORT 38 AL JUMAIL VILLAGE 40 Cultural AND natural heritage 43 AL JassasIYA Rock CARVING SITE 44 JAZIRat BIN GHANNAM 48 RAS ABROUQ, ZEKREET FORT AND 50 East-WEst/WEst-East BY RICHARD SERRA For general inquiries please contact QM Cultural Tourism Unit: OTHER Information 55 THINGS to havE IN MIND WHEN VISITING 56 Division of Cultural Heritage Cultural Tourism Unit [email protected] +974 4402 8305 School visit to Al Zubarah Fort OTHER INFORMATION – LOCATION MAP 4 5 TAKING QM BEYOND THE WALLS HERITAGE SITES LOCATION – – LEGEND LOCATION MAP AL RUWAIS PARKING Road -

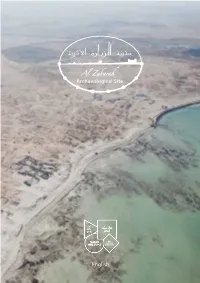

Al Zubarah Archaeological Site: Information Booklet

English Foreword The town of Al Zubarah, Qatar’s largest archaeological site, lies on the country’s northwest coast 85km from Doha. This now abandoned town was once a thriving cultural and political centre with an economy based on pearl fishing and trade. As one of the largest and best preserved examples of an 18th-19th century merchant town anywhere in the Arabian Gulf, Al Zubarah is an outstanding testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the Gulf Arabs. This booklet provides some basic information about the history of the site, the Al Zubarah Fort and the ongoing excavations. Qatar Museums invites you to visit and enjoy the first Qatari site inscribed into the UNESCO World Heritage List and learn about the heritage, traditions, history and development of Qatar. Most visitors arrive at the Al Zubarah Fort which is home to a new visitor centre. We suggest you begin your tour here, before exploring the archaeological site on the coast. Please follow the site rules and regulations to help us protect and preserve this important site for future generations. We hope you enjoy your visit. The Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project is an initiative by the Qatar Museums Chairperson H. E. Sheikha Al Mayassa Bint Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani and Vice-Chairman H. E. Sheikh Hassan Bin Mohammed Al Thani Cover image: Al Zubarah shore from the air 1 Contents Al Zubarah: The First World Heritage Site in Qatar Page 3 Al Zubarah Fort Food in Al Zubarah Page 5 Page 23 Qalat Murair Archaeological Site The Importance of Dates Page 7 Page 25 -

2020 World Lng Report

2020 WORLD LNG REPORT Sponsored by RE Advertorial_International Gas Union - LNG Report_Print_FA.pdf 1 4/8/2020 11:16:51 PM IGU World LNG report - 2020 Edition 4 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2 3 IGU World LNG report - 2020 Edition Message from the Chapter 1: State of the Table Of Contents President of the LNG Industry International Gas Union 7 8 Chapter 2 : LNG Trade Chapter 3 : LNG and Gas Chapter 4 : Liquefaction Chapter 5 : Shipping Pricing Plants 2.1 Overview 4.1 Overview 5.1 Overview 2.2 LNG Exports by Market 4.2 Global Liquefaction Capacity and Utilisation 5.2 LNG Carriers 2.3 LNG Imports by Market 4.3 Liquefaction Capacity by Market 5 . 3 F l o a t i n g S t o r a g e a n d R e g a s i fi c a t i o n U n i t 2.4 LNG Interregional Trade 4.4 Liquefaction Technologies Ownership (FSRUs) 4.5 Floating Liquefaction 5.4 2020 LNG Orderbook Map: Global LNG Liquefaction Terminals 5.5 Vessel Costs and Delivery Schedule 4.6 Risks to Project Development 5.6 Charter Market 4.7 Update on New Liquefaction Plays 5.7 Fleet Voyages and Vessel Utilisation 4.8 Refrigeration Compressor Driver Map: Major LNG Shipping Routes Developments 5.8 Near Term Shipping Developments 10 22 28 52 Chapter 6 : LNG Receiving Chapter 7 : The LNG Chapter 8 : References Appendices Terminals Industry in Years Ahead 6.1 Overview 8.1 Data Collection for Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6 1. -

The LNG Industry

The LNG industry GIIGNL ANNUAL REPORT 2019 REPORT GIIGNL ANNUAL GIIGNL ANNUAL REPORT2019 GIIGNL is a non-profit organisation whose objective is to promote the development of activities related to LNG: purchasing, importing, processing, transportation, handling, re-gasification and its various uses. The Group constitutes a forum for exchange profile of information and experience among its 81 members to enhance safety, reliability and efficiency of LNG import activities and the operation of LNG import terminals in particular. GIIGNL has a worldwide focus and its membership is composed of nearly all companies in the world active in the import and regasification terminalling of LNG. Key Figures 02 LNG trade in 2018 04 Contracts concluded in 2018 06 Medium-term and long-term contracts in force in 2018 08 LNG shipping 14 LNG imports in 2018 24 Liquefaction plants 32 contents Regasification terminals 37 World LNG Maps 46 Retail LNG in 2018 50 About GIIGNL 51 © GIIGNL - International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers All data and maps provided in this publication are for information purposes and shall be treated as indicative only. Under no circumstances shall they be regarded as data or maps intended for commercial use. Reproduction of the contents of this publication in any manner whatsoever is prohibited without prior consent of the copyright owners. (Photo credits: © Elengy_Arnaud Brunet, Höegh LNG (cover) ; Inpex Corporation Mitsui O.S.K. Lines Ltd. ; Novatek ; Tokyo Gas Co. Ltd. ; AES) EDITORIAL The LNG industry in 2018 by the EU and US statement of intent in July or by the reciprocal tariff increase between US and China in September. -

World Heritage Youth Forum Qatar 2014

WORLD HERITAGE YOUTH FORUM QATAR 2014 Cultural Heritage of Qatar: Management, Preservation, Sustainability and Impact on Local Communities Al Zubarah and Doha, 04-15 June 2014 In conjunction with the 38th Session of the World Heritage Committee OBJECTIVES Understanding the 1972 Convention and the challenges of its implementation Raising awareness among participants of cultural heritage in their countries Explaining the role of public archaeology and local communities in heritage management Providing young people with skills related to preservation and conservation Explaining to young people how the World Heritage Committee works PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME Tuesday, 03-04 June 2014 [DOHA] 07:30 Morning and afternoon arrivals of participants in Doha: welcome at the dedicated UNESCO desk at the airport Transfer and check-in at Sharq Village and Spa Hotel 12:00 Lunch Registration 19:00 Dinner Wednesday, 04 June 2014 [DOHA] 14:00 Registration for late arrivals 16:30 General briefing 18:00 Tour of the hotel and facilities 19:00 Welcome dinner Thursday, 05 June 2014 [DOHA] 07:30 Breakfast at hotel 09:30 Opening ceremony Welcome addresses H.E. Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums Authority; H.E. Sheikh Hassan bin Mohammed Al-Thani, Vice Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Qatar Museums Authority Dr. Anna Paolini, Director of UNESCO Doha Office H.E. Mr. Ali Zainal, Ambassador and Permanent Delegate of the State of Qatar to UNESCO 10:00 Coffee Break 11:00 12:00 Introductory speeches The World Heritage Convention and the 38thSession of the WHC Framework and Objectives of the Youth Forum 12:00 14:00 Lunch at hotel 14:00 15:00 Group discussion and Plenary 15:00 16:30 Film on the Development of Qatar Presentation led by Ms. -

New Decree Offers Big Incentives to Investors

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Barshim in shortlist for top INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-7, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 QFC is eyeing IAAF prize REGION 8 BUSINESS 1-7, 12-16 Turkish businesses 23,552.33 8,014.71 57.09 ARAB WORLD 8 CLASSIFIED 8-12 +13.14 -112.18 +1.45 INTERNATIONAL 9-21 SPORTS 1-8 +0.06% -1.38% +2.61% in a big way Latest Figures TUESDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10630 November 7, 2017 Safar 18, 1439 AH www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals GULF TIMES Emir meets Volkswagen chairman New decree In brief offers big QATAR | Religion Prayer for rain to be performed on Thursday The Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs has called on all Muslims in the incentives State to perform Istisqa (rain-seeking) prayer on Thursday (20 Safar 1439/ November 9) in line with the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). In a statement, the ministry called His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met yesterday at the Emiri Diwan with Volkswagen Group Supervisory for the performance of the prayer at Board Chairman Hans Dieter Poetsch. The meeting dealt with boosting co-operation ties. the State’s mosques at 06.01am. to investors QATAR | Event Emir issues Decree Law No 21 of 2017, amending some Safety and security provisions of Law No 34 of 2005 on Investment Free Zones meet kicks off today is Highness the Emir Sheikh ated the local, regional and interna- Under the patronage of HE the Prime Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani is- tional developments for achieving Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Qatar Airways buys 9.6% H sued yesterday Decree Law No the nation’s economic targets and at- Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa al- 21 of 2017, amending some provisions tract local and foreign investments. -

2018 78 Member Companies in 26 Countries

The LNG industry GIIGNL ANNUAL REPORT 2018 78 MEMBER COMPANIES IN 26 COUNTRIES GIIGNL (International Group of LNG Importers) is the worldwide association of LNG importers. EUROPE 30 Founded in 1971, at the outset of the LNG industry, AMERICAS members ASIA its membership has grown to 78 companies worldwide, 11 37 members members comprising nearly all companies active in LNG imports or in the operation of LNG terminals. It is a non-profit organization and its resources only come from the membership fees. The association constitutes a forum for exchange of experience among its members, with a view to enhance safety, reliability and efficiency of LNG imports. GIIGNL members are coming from 26 countries headquartered in the main three regions: Americas, 11 members, Asia, 37, Europe, 30. Full Members Elengy S.A. Guangdong Dapeng LNG Company, Ltd. National Grid Grain LNG, Ltd. Southern LNG Company, L.L.C. Associate Members BOTAŞ Enagas Hazira LNG Private Ltd. Nippon Gas Co., Ltd. South Hook LNG Terminal Company, Ltd. EDF Trading Limited BP Global LNG Enel Trade SpA Hiroshima Gas Co., Ltd. N.V. Nederlandse Gasunie Sumitomo Corporation ENN LNG Trading Company Limited Centrica LNG Company ENGIE Höegh LNG Osaka Gas Co., Ltd. TEPCO Fuel & Power, Inc. Gazprom Marketing & Trading Limited Cheniere Energy, Inc. ENGIE Gas and LNG, LLC Hokkaido Gas Co., Ltd. Pakistan LNG Limited (PLL) The Chugoku Electric Power Co., Inc. GSPC LNG Limited Chubu Electric Power Co., Inc. Eni S.p.A. Iberdrola Generación España, S.A.U. Petronet LNG Limited The Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc. INPEX Corporation CNOOC Gas & Power Trading & Excelerate Energy L.P. -

Al Zubarah Archaeological Site (Qatar) No 1402Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Al Zubarah Archaeological Site Fund for preparing the Nomination None (Qatar) No 1402rev Date received by the World Heritage Centre 31 January 2011 31 January 2013 Background Official name as proposed by the State Party This is a referred back nomination. Al Zubarah Archaeological Site At its 36th session (Saint-Petersburg, 2012), the World Location Heritage Committee adopted the following decision: Madinat Ash Shamal Municipality State of Qatar Decision: 36 COM 8B.19 Brief description The World Heritage Committee, The walled coastal town of Al Zubarah flourished for a 1. Having examined Documents WHC-12/36.COM/8B and short period of some fifty years in the late 18th and early WHC-12/36.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Refers the nomination of Al Zubarah Archaeological Site, 19th centuries, when it was one of the most important Qatar, back to the State Party, in order to allow it to: pearling and trading centres in the Persian Gulf. a) Further develop its understanding of how the fabric of Al What distinguishes Al Zubarah from other towns is the Zubarah and its desert hinterland were an exceptional fact that it was abandoned and its layout has been testimony to a specific interaction between nomadic preserved under the desert sands. The remains of the herders, pearl divers, fishermen and traders that once entire town, still within its desert hinterland, are a characterised the way of life in the Gulf by: reflection of the development of an eighteenth- and i. Presenting the results of surveys and excavations carried out in the property and its wider setting, nineteenth-century trading society in the Gulf region and including underwater archaeology, that have already its interaction with the surrounding coastal and desert permitted the understanding of the origins of the settlements.