Issues and Challenges Related to Local Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention 2012 News in This Issue!

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association APRIL 2012 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Watching TV Outside on a Rare Warm Evening in March SEE SOME REALLY NICE CENTRAL AMERICAN DX PHOTOS IN THIS MONTH’S PHOTO NEWS MORE CONVENTION 2012 NEWS Visit Us At www.wtfda.org IN THIS ISSUE! THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info _______________________________________________________________________________________ Welcome to the April VUD! It seems that summer has kicked into gear in many parts of North America a little early. The grass is turning green, the trees are beginning to bud and the snow shovels are put away for the season. There’s been a little bit of tropo. There’s been a little bit of skip in the south. There’s also been some horrible storms and tornados in places. We hope everyone is okay and stayed out of danger. This month we find that Ken Simon (Lake Worthless, FL) has rejoined the club. -

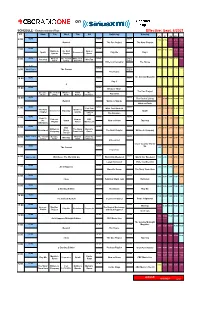

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Broadcasting & Convergence

1 Namnlöst-2 1 2007-09-24, 09:15 Nordicom Provides Information about Media and Communication Research Nordicom’s overriding goal and purpose is to make the media and communication research undertaken in the Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – known, both throughout and far beyond our part of the world. Toward this end we use a variety of channels to reach researchers, students, decision-makers, media practitioners, journalists, information officers, teachers, and interested members of the general public. Nordicom works to establish and strengthen links between the Nordic research community and colleagues in all parts of the world, both through information and by linking individual researchers, research groups and institutions. Nordicom documents media trends in the Nordic countries. Our joint Nordic information service addresses users throughout our region, in Europe and further afield. The production of comparative media statistics forms the core of this service. Nordicom has been commissioned by UNESCO and the Swedish Government to operate The Unesco International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, whose aim it is to keep users around the world abreast of current research findings and insights in this area. An institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordicom operates at both national and regional levels. National Nordicom documentation centres are attached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. NORDICOM Göteborg -

Independent Broadcaster Licence Renewals

February 15, 2018 Filed Electronically Mr. Chris Seidl Secretary General Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0N2 Dear Mr. Seidl: Re: Select broadcasting licences renewed further to Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2017-183: Applications 2017-0821-5 (Family Channel), 2017-0822-3 (Family CHRGD), 2017- 0823-1 (Télémagino), 2017-0841-3 (Blue Ant Television General Partnership), 2017-0824-9 (CHCH-DT), 2017-0820-8 (Silver Screen Classics), 2017-0808-3 (Rewind), and 2017-0837-2 (Knowledge). The Writers Guild of Canada (WGC) is the national association representing approximately 2,200 professional screenwriters working in English-language film, television, radio, and digital media production in Canada. The WGC is actively involved in advocating for a strong and vibrant Canadian broadcasting system containing high-quality Canadian programming. Given the WGC’s nature and membership, our comments are limited to the applications of those broadcasters who generally commission programming that engages Canadian screenwriters, and in particular those who significantly invest in programs of national interest (PNI). The WGC conditionally supports the renewal of the above-noted services, subject to our comments below. Executive Summary ES.1 The Commission set out its general approach to Canadian programming expenditure (CPE) and PNI requirements in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2015-86, Let’s Talk TV: The way forward - Creating compelling and diverse Canadian programming (the Create Policy). In it, the Commission was clear that CPE was a central pillar of the regulatory policy framework for Canadian television broadcasting, and that the guiding principle for setting CPE levels for independent broadcasters would be historical spending levels. -

Summary of the Corporate Plan

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Summary of the Corporate Plan for the period 1999/00 to 2003/04 1.1.1.1.1 The Corporate 1.1.1.1.2 Su August 1999 OPENING REMARKS In a fast-changing and often turbulent world, the role of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation has remained constant -- from its creation as an Act of Parliament in 1936 to its rejuvenation at the turn of a new century. The CBC exists to serve Canadians. That duty is as simple in its definition as it is complex in its execution. The CBC is preparing to enter the most innovative and perhaps most challenging era of broadcast history, with a five-year Corporate Plan to chart its course, a clear vision and a strengthened resolve. Technology has unleashed a multi-channel and multimedia universe, one that cannot be held back by either artificial barriers or by well-meaning national sentiment. Never before has it been more important that Canadians have an established and trusted vehicle to carry their voices and their stories to each other and to the world at their fingertips. Never before has it been more essential that the CBC be given the flexibility and the freedom to grow alongside the people who depend upon it. After more than a decade of uncertainty, the CBC faces a future based more on the opportunities before it than the limitations that clouded its past. Stable federal funding has aided our ability to plan but the overall financial imperatives have been permanently altered and challenges will continue. We are confident, however, that our plans will allow the CBC to build upon its strengths and extend its reach within the familiar forms of radio and television and outward to the dynamic and evolving realm of cyberspace that will determine Canada’s place in the 21st century. -

CMCRP : the Growth of the Network Media Economy in Canada

THE GROWTH OF THE NETWORK MEDIA ECONOMY IN CANADA, 1984-2017 REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 (UPDATED JANUARY 2019) Canadian Media Concentration Research Project Research Canadian Media Concentration www.cmcrp.org 2 Candian Media Concentration Research Project The Canadian Media Concentration Research project is directed by Professor Dwayne Winseck, School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University. The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and aims to develop a comprehensive, systematic and long-term analysis of the media, internet and telecom industries in Canada to better inform public and policy-related discussions about these issues. Professor Winseck can be reached at either [email protected] or 613 769- 7587 (mobile). Open Access to CMCR Project Data CMCR Project data can be freely downloaded and used under Creative Commons licens- ing arrangements for non-commercial purposes with proper attribution and in accor- dance with the ShareAlike principles set out in the International License 4.0. Explicit, written permission is required for any other use that does not follow these principles. Our data sets are available for download here. They are also available through the Dat- averse, a publicly-accessible repository of scholarly works created and maintained by a consortium of Canadian universities. All works and datasets deposited in Dataverse are given a permanent DOI, so as to not be lost when a website becomes no longer avail- able—a form of “dead media”. Acknowledgements Special thanks to Ben Klass, a Ph.D. student at the School of Journalism and Communi- cation, Carleton University, Lianrui Jia, a Ph.D student in the York Ryerson Joint Gradu- ate Program in Communication and Culture and Han Xiaofei, also in the Ph.D. -

The Magazine for TV and FM Dxers

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association JUNE 2010 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Ch4 Santa Marta Colombia(Caracol) Ch2 Caracas Venezuela(Tves) May 3rd Double Hop E skip! Bill Hepburn Sees Colombia and Venezuela in Color! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org Cover Photos by Bill Hepburn THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info JUNE 2010 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 5 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 12 secure way to join or renew your membership FCC Facilities Changes 16 in the WTFDA. Just logon to Paypal and send Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 20 your dues to [email protected]. Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 22 Use the address above to either join the 6 meters…Peter Baskind 33 WTFDA or renew your membership in North Eastern TV DX…Nick Langan 34 America’s only TV and DX organization. -

The Public/Private Tension in Broadcasting the Canadian Experience with Convergence

The Public/Private Tension in Broadcasting The Canadian Experience with Convergence John D. Jackson & Mary Vipond Canada’s Broadcasting Act designates Canadian broadcasters, public and private alike, as a single system to which the Act and all subsequent regula- tions apply. The Act is based on the premise that the airwaves are public property, but allows for the existence of a private sector within the whole (Canada, 1991). Thus does it signal: (1) the tension between the public good and private gain; (2) the fact of a particular relation between private and public broadcasting in Canada; and (3) the possibility that the relationship may simultaneously address issues of national sovereignty and benefit capi- tal accumulation. These themes will be placed in the context of Canada’s economic culture and the current process of corporate convergence. Though convergence is presently taking place on several fronts – across media plat- forms, within media platforms, and across distribution technologies – we concentrate on the first of these and on the implications for the public remit. The convergence of broadcasting, production, distribution and print raise two important issues. First there is a very real anxiety over the possibility that cross-media convergence will reduce the variety of voices expected from an open broadcasting system (public and private alike). Secondly, there is concern that national and regional public broadcasting units may, in the end, carry the principal responsibility for ensuring a multiplicity of voices. Indeed, and somewhat ironically, national public broadcasting may well be the sole defence against monopoly. Convergence within specific media platforms, across media platforms, and across modes of delivery has reduced the sheer number of independent and competitive players in the market. -

Of Analogue: Access to Cbc/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery

THE END(S) OF ANALOGUE: ACCESS TO CBC/RADIO-CANADA TELEVISION PROGRAMMING IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL DELIVERY by Steven James May Master of Arts, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Applied Arts (Honours), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1999 Bachelor of Administrative Studies (Honours), Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1997 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Steven James May, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The End(s) of Analogue: Access to CBC/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery Steven James May Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University, 2017 This dissertation -

Of Logos, Owners, and Cultural Intermediaries: Defining an Elit

Of Logos, Owners, and Cultural Intermediaries: Defining an Elite Discourse in Re-branding Practices at Three Private Canadian Television Stations Christopher Ali University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the relationship between local television stations and na - tional networks through a careful study of station re-branding. The relationship is explored through case studies of the three privately owned English-speaking television stations in Win - nipeg, Canada. Through in-depth interviews with station and network executives, the author investigates the critical factors that facilitated the re-branding of Canada’s private television networks between 1997 and 2005. This period saw many English-speaking television networks unite their respective affiliate stations under a single logo and brand. Influenced by branding theory and scholarship on Canadian broadcasting, this article examines the shift away from local identification in Canadian broadcasting and the benefits, challenges, and resistances therein. KEYWORDS Canadian broadcasting; Local television; History of broadcasting; Branding RÉSUMÉ Cet article explore le rapport entre les stations de télévision locales et les réseaux nationaux au moyen d’un examen méticuleux des changements de marque des stations. Pour ce faire, l’auteur a mené des études de cas sur les trois stations de télévision privées de langue anglaise à Winnipeg, Manitoba. En se fondant sur des entretiens en profondeur avec des cadres de stations et de réseaux, l’auteur explore les facteurs critiques qui ont permis les changements de marque des réseaux de télévision privés au Canada entre 1997 et 2005. C’est durant cette période que plusieurs réseaux de télévision anglophones ont uni leurs stations affiliées respectives sous la bannière d’un seul sigle et d’une seule marque. -

1 Modernisms on the Air: CBC Radio in the 1960S Jeremy Strachan

Modernisms on the Air: CBC Radio in the 1960s Jeremy Strachan, Cornell University To reflect a nation’s culture—and help create it—a broadcasting system must not minister solely to the comfort of the people. It must not always play safe. Its guiding rule cannot be to give the people what they want, for at best this can be only what the broadcasters think the people want; they may not know, and the people themselves may not know. One of the essential tasks of a broadcasting system is to stir up the minds and emotions of the people, and occasionally to make large numbers of them acutely uncomfortable. —Report of the Committee on Broadcasting (the Fowler Report), 19651 Introduction In the 1960s, contemporary music became a more audible part of Canadian life. The Canadian Music Centre and the Canada Council for the Arts had emerged as bulwarks of support for Canadian composers, who had relied on patchwork networks for resources, promotion, and advocacy2; adventurous independent presenters such as Ten Centuries Concerts in Toronto and the Société de musique contemporain du Québec in Montreal had begun to stake out territory on concert stages, programming concerts of new and “unheard of” musics;3 and, the centennial celebrations of 1967 produced nearly 130 new musical works by Canadian composers.4 Throughout the decade, CBC Radio and Radio-Canada5 played a central part in disseminating musical modernisms with weekly programs such as World of Music (until 1963) and Music of Today (from 1964 through to 1977), in addition to special programs, live concert broadcasts, and in 1967, Canada’s centennial year, the ambitious seventeen-LP series Music and Musicians of Canada produced by the CBC’s International Service in partnership with RCA Victor. -

Canadian Television 2020: Technological and Regulatory Impacts

Canadian Television 2020: Technological and Regulatory Impacts Nordicity Peter Miller, P. Eng., LL.B Prepared for: ACTRA Canadian Media Guild Directors Guild of Canada Friends of Canadian Broadcasting Unifor December 2015 Peter H. Miller, P. Eng., LL.B. Preamble This report was prepared by Nordicity and Peter Miller, P. Eng., LL.B. for ACTRA, Canadian Media Guild, Directors Guild of Canada, Friends of Canadian Broadcasting and Unifor. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this report are those of the Authors and not necessarily those of the commissioning parties. ABOUT NORDICITY Nordicity is a leading consulting firm specializing in policy, strategy, and economic analysis in the media, creative and information and communications technology sectors. Over the last three decades, Nordicity has become widely recognized as one of the leading international consultancies specializing in economic analysis and business planning within the television broadcasting sector. ABOUT PETER MILLER Peter is an engineer and communications lawyer with 25 years of creative and telecommunications industry experience, in both private practice and executive positions. Since 2005, he has acted as an advisor for select clients in both the public and private sectors, and has authored numerous reports on technological and policy trends and their impact on the media landscape. Peter H. Miller, P. Eng., LL.B. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Part A. Environmental Scan 14 1. Objective of Study 14 2. Summary of Research and Analysis 16 2.1 Gradually then Suddenly: