MSNA Language Data Can Help Humanitarians Communicate Better with Affected People December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sambisa Final Draftnh

Total Aerial Count of Elephants and other Wildlife Species in Sambisa Game Reserve in Borno State, Nigeria By P. Omondi1, R. Mayienda2, Mamza, J.S.3, M.S. Massalatchi4 All correspondences E-mail: [email protected] JULY 2006 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY .................................................................................................................................. 6 STUDY AREA..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 CLIMATE ........................................................................................................................................................................... 7 SOIL................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 FLORA & FAUNA .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Monguno Bama Gwoza

DTM Flash Report Windstorm and rainfall damages to IDP sites Nigeria IOM DTM Rapid Assessment Monguno, Bama and Gwoza LGAs (Local Government Areas) 24 June 2021 SUMMARY PP PPPP 200 Households 671 Individuals 3 sites 130 Damaged shelters 11 Damaged toilets 8 Damaged shower points With the onset of the rainy season in Nigeria’s conflict-affected Kukawa Guzamala northeastern state of Borno, varying degrees of damages are expected to GGSS 431 Camp Gubio ± infrastructures (self-made and constructed) in camps and camp-like settings. Usually, heavy rainfalls are accompanied by strong winds Nganzai Monguno causing serious damage to shelters of IDPs. Marte Between 17 and 23 June 2021, IOM’s DTM programme carried out Ngala assessments to ascertain the level of damage sustained in camps and Magumeri camp-like settings due to heavy windstorms and rainfall. Overall, 2 Kala/Balge Mafa Jere camps and 1 collective settlement in the LGAs Monguno, Bama and Dikwa Gwoza LGAs were assessed. The worst-hit of the camps assessed was Maiduguri Goverment Girls Secondary School (GGSS) camp in Monguno LGA where a heavy rainfall damaged 33 shelters, affecting an estimated 431 GSSSS camp individuals. Konduga 225 Bama In total, 130 shelters were damaged by storms, leaving a total of 200 households without shelter. Additionally, a total of 11 toilets and 8 Gwoza showers were damaged by storms. There was no casualty as a result of 20 Housing XXX Affected population Damboa 15 Camp the storms. Per Location LGA Sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, Intermap, INCREMENT P, NRCan, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China 0 5 10 20 30 40 Affected LGAs (Hong Kong), Esri Korea, Esri (Thailand), NGCC, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Miles Community, Esri, HERE, Garmin, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS user community The maps in this report are for illustra�on purposes only. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

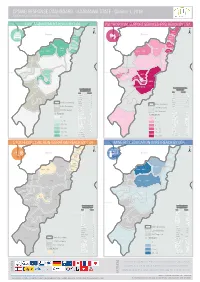

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

Gwoza 1917 987 4239 Bama 2143 1026 5250 Mobbar 1212 411

IDPs DATA S.O.E STATES BORNO, YOBE AND ADAMAWA FROM JANUARY TO MARCH, 2014 TOTAL - 129,624 77,077 37,870 244,070 5,376 249,446 3,161,887 Number of IDPs living Number of Number Of Number of Number of with host IDPs in Total Number Total Affected STATE LGA Affected Children Women Men families Camps of IDPs Population Date of ocuranceNature of Disaster Borno GWOZA 1917 1335 987 4239 4,239 276,568 11/01/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 2143 2081 1026 5250 5,250 270,119 13/01/2014 INSURGENCY MOBBAR 1212 727 411 2350 2,809 5,159 116,631 24/01/2014 INSURGENCY JERE 891 606 367 1864 1,864 209 24/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 97 88 24 209 209 233,200 26/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 118 113 38 269 567 836 836 26/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 330 287 131 748 748 748 22/01/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 1206 592 313 2111 2,111 157,322 02/02/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 1511 1007 603 3121 3,121 3,121 05/02/2014 INSURGENCY GWOZA 1723 1215 805 3743 3,743 3,743 13/02/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 2343 2099 1036 5478 5,478 5,478 14/02/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 65 67 30 162 162 162 14/02/2014 INSURGENCY GWOZA 4403 2423 1309 8135 8,135 8,135 19/02/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 2398 1804 911 5113 5,113 5,113 20/02/2014 INSURGENCY MMC 2289 1802 900 4991 4,991 4,991 01/03/2014 INSURGENCY KAGA 1201 582 303 2086 2,086 89,996 01/03/2014 INSURGENCY MAFA 2015 913 568 3496 3,496 3,496 02/03/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 1428 838 513 2779 2,779 2,779 03/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 2437 2055 1500 5992 5,992 5,992 04/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 170 133 57 360 360 360 05/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 406 343 211 960 960 960 06/03/2014 -

PSWG Actors Oct 2016

protectionsector COMPLETED AND W O R K I N G G R O U P NIGERIA: PROTECTION ACTORS ON-GOING ACTIVITIES N I G E R I A Agencies with registered projects in OCHA Online Project Systems (OPS) JAN - OCT 2016 COOPI (Cooperazione Internazionale) DRC (Danish Refugee Council) IOM (International Organization for Migration) POPULATION POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 3,168 REACHED 13,363 REACHED 92,911 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation 3,168 10,988 66,908 JERE DIKWA MAIDUGURI 28 MAIDUGURI DAMATURU DAMATURU POTISKUM KONDUGA BAMA FIKA GWOZA BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY CHIBOK GOMBE GOMBE MICHIKA GOMBE MUBI 2 Case Referrals NORTH GIRERI GIRERI BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY 54 Capacity Building BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY Unaccompanied and ADAMAWA 947 Multiple Needs ADAMAWA ADAMAWA 2 63 Livelihood Separated Children YOLA YOLA SOUTH NORTHYOLA Unaccompanied and YOLA Protection SOUTH 24 Multiple Needs 2,221 NORTH 82 Separated Children Mainstreaming FUFORE 2,375 25,975 175 Case Referrals 176 Awareness Raising / Sensitization 293 Capacity Building 271 Material Protection Assistance Psychosocial Distress Identification of 92,417 and Mental Disorder 3 6 1,727 Vulnerable Individuals 12 LOCAL GOVERNMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNIT COVERED UNIT COVERED 10,988 Dangers and Injuries UNIT COVERED NRC IRC (International Rescue Committee) NRC (Norwegian Refugee Council) Mercy Corps POPULATION POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 165,191 REACHED -

FEWS NET Special Report: a Famine Likely Occurred in Bama LGA and May Be Ongoing in Inaccessible Areas of Borno State

December 13, 2016 A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State This report summarizes an IPC-compatible analysis of Local Government Areas (LGAs) and select IDP concentrations in Borno State, Nigeria. The conclusions of this report have been endorsed by the IPC’s Emergency Review Committee. This analysis follows a July 2016 multi-agency alert, which warned of Famine, and builds off of the October 2016 Cadre Harmonisé analysis, which concluded that additional, more detailed analysis of Borno was needed given the elevated risk of Famine. KEY MESSAGES A Famine likely occurred in Bama and Banki towns during 2016, and in surrounding rural areas where conditions are likely to have been similar, or worse. Although this conclusion cannot be fully verified, a preponderance of the available evidence, including a representative mortality survey, suggests that Famine (IPC Phase 5) occurred in Bama LGA during 2016, when the vast majority of the LGA’s remaining population was concentrated in Bama Town and Banki Town. Analysis indicates that at least 2,000 Famine-related deaths may have occurred in Bama LGA between January and September, many of them young children. Famine may have also occurred in other parts of Borno State that were inaccessible during 2016, but not enough data is available to make this determination. While assistance has improved conditions in accessible areas of Borno State, a Famine may be ongoing in inaccessible areas where conditions could be similar to those observed in Bama LGA earlier this year. Significant assistance in Bama Town (since July) and in Banki Town (since August/September) has contributed to a reduction in mortality and the prevalence of acute malnutrition, though these improvements are tenuous and depend on the continued delivery of assistance. -

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde Madagali Maiha Mayo Belwa Michika Mubi North Mubi South Numan Toungo Shellenge Song Yola North Yola South PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Along Gombe Road, Demsa Town, Demsa Local Govt. Area Gurin Road, Adjacent Local Govt. Guest House, Fufore Local Govt. Area Along Federal Government College, Ganye Road, Ganye Lga Adjacent Local Govt. Guest Road, Girei Local Govt. Area Sangere Gombi, Aong Yola Road, Gombi L.G.A Palamale Nepa Ward Guyuk Town, Guyuk Local Govt. Area Opposite Cottage Hospital Shangui Ward, Hong Local Govt. Area Old Secretariat, Jada Along Ganye Road, Jada Lafiya Lamurde Road, Lamurde Local Govt. Area Palace Road, Gulak, Near Gulak Police Station, Madagali Lga Behind Local Govt. Secretariat, Mayonguli Ward, Maiha Jalingo Road Near Maternity Mayo Belwa Lga Michika Bye-Pass Zaibadari Ward Michika Lga Inside Local Govt. Secretariat, Mubi North Lumore Street, Opposite District Head's Palace, Gela, Mubi South Councilors Quarters, Off Jalingo Road, Numan Lga Barade Road, Oppoiste Sss Office, Toungo Old Local Govt Secretariat Street, Shelleng Town, Shelleng Lga Opp. Cattage Hospital Yola Road, Song Local Govt. Area No. 7 Demsawo Street, Demsawo Ward, Yola North Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga. -

Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020)

Nigeria: Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020) Number of Local Reporting PARTNERS PER TYPE Government Area Partners OF ORGANIZATIONS BREAKDOWN OF PEOPLE REACHED PER CATEGORY NGOs/UN People Reached PiN/Target IDP Returnee Host Agencies Community 21 Partners14 including 230,996 LGAs with ongoing International NGOs and activities 95,764 13,922 1,268 80,573 UN Agencies 11/3 212,433 DEMSA (4 Partners) MICHIKA (6 Partners) FSACI, IOM, JHF, WHO GZDI, IRC, JHF, PLAN, WHO, ZSF MADAGALI REACHED: 6,070 REACHED: 6,578 FUFORE (4 Partners) MUBI NORTH (7 Partners) MICHIKA GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, PLAN, IOM, JHF, UNICEF, WHO SWOGE, WHO REACHED: 17,309 REACHED: 6,924 MUBI NORTH GANYE (2 Partners) MUBI SOUTH (6 Partners) HONG JHF GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, RHHF, ZSF GOMBI MUBI SOUTH REACHED: - REACHED: 4,090 GIREI (4 Partners) NUMAN (1 Partner) SHELLENG JHF AGUF, IOM, JHF, WHO MAIHA REACHED: 22,348 REACHED: - SONG GUYUK GOMBI (3 Partners) SHELLENG (1 Partner) JHF GDZI, JHF, WHO LAMURDE REACHED: 220 REACHED: - GIREI GUYUK (2 Partners) SONG (2 Partners) NUMAN AGUF, JHF JHF DEMSA REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 YOLA SOUTH YOLA NORTH HONG (3 Partners) TOUNGO (1 Partner) GDZI, JHF, WHO JHF MAYO FUFORE REACHED: 423 REACHED: - BELWA JADA (1 Partner) YOLA NORTH (4 Partners) HARAF, IOM, JHF, UNICEF JHF JADA REACHED: - REACHED: 1,224 LAMURDE (1 Partner) YOLA SOUTH (4 Partners) GANYE JHF IOM, JHF, SWOGE, UNICEF Number of Organizations REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 (3 Partners) MADAGALI 1 7 JHF, PLAN, WHO TOUNGO REACHED: 4,537 MAIHA (2 Partners) JHF, WHO -

Site Suitability for Yam, Rice and Cotton Production in Adamawa State of Nigeria: a Geographic Information System (Gis) Approach

FUTY Journal of the Environment, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2009 45 © School of Environmental Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Yola-Nigeria. ISSN 1597-8826 © School of Environmental Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Yola-Nigeria. ISSN 1597-8826 SITE SUITABILITY FOR YAM, RICE AND COTTON PRODUCTION IN ADAMAWA STATE OF NIGERIA: A GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS) APPROACH. M. Ikusemoran and T. Hajjatu Department of Geography, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria. ABSTRACT This paper demonstrated the potentials of GIS technique for mapping and delineating the suitable sites for Yam, Rice and Cotton production in Adamawa State. Site suitability mapping is necessary to create data bank and to guide the farmers in decision making on sites for crop production in the state. The use of GIS for this decision making introduces reliability and saves time with a consequent increase in agricultural productivity. The six criteria that were used for the study include soil, topography, vegetation, temperature, annual rainfall and lengths of rainy season. A combination of Ilwis 3.0 Academics, Arcview GIS 3.0 and Idrisi 32 were used for data capture and analysis. Using Boolean operations on the six criteria, and based on the requirements for each crop, all the areas that met the six conditions were considered “most suitable”. The areas with five conditions were assigned “suitable”, while the areas with four and/or three criteria were considered “just suitable”. The areas that were considered unsuitable are those areas that met no condition or the areas that met only one or two conditions. The study revealed that yam production in the state is “most suitable” in only Ganye Jada and Toungo Local Government Areas (LGA) in the Southern part of the state, covering only 5.05% of the state land mass. -

Week 29 Report

CCCM - NIGERIA Multi Sector Tracker weekly report Date of report 29 July 2017 17 to 23 July 2017 (Week 29) INTRODUCTION The site tracker is a weekly gap analysis and monitoring of services tool used by the site facilitators and site management agencies, in support of the Government camp management agencies and in areas with no camp managers, to identify and refer gaps in delivery and assistance in IDP sites. It enables stakeholders to track activities and avoid duplication of eorts, in support of the sectors as a basis of follow-up on quality of services delivered. It contributes to speed up the time of response by concerned partners and avoid unnecessary delays. As of July 2017, over 87 camps are covered in Borno and Adamawa by the IOM site facilitators in support of the Government Site Managers, either dedicated or mobile team, to strengthen camp management mechanisms and coordination of delivery. The areas sites covered are located in the following LGAs: Girei,Yola South, Yola North and Fufore. The report must not be misconstrued to represent the situation of all IDP camps in North-eastern Nigeria and covers only the sites in review during the week. 17 Sites in, GIREI, YOLA NORTH and YOLA SOUTH LGAs in ADAMAWA State in review this week GIREI EYN CHURCH VINIKILANG, SEGERE DUTSE, CHEKAMIDERI, LOWCOST QUARTERS, NANA VILLA, UNGWAN ABUJA FUFORE DAWARE CAMP, WURO AHI, FUFORE CAMP YOLA ST. THERESAS CATHEDRAL NORTH YOLA MALKOHI CAMP, DOKKITILLA WUROCHEKKE, HULLERE, SABON DEAL NGURORE, MALKOHI VILLAGE, KILBAJE EXTENSION SOUTH Yobe Borno Adamawa