ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 561 the STATUS of the Birds Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Leader Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge

Project Leader Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge Location Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial is located 1,300 miles from the main Hawaiian Islands and is part of the Northwestern Hawaiian Island chain. In addition to being a refuge and national memorial, Midway Atoll is also a part of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the largest protected areas in the world. Midway Atoll is recognized as globally important for breeding albatross and other seabirds, and for its historic and cultural significance. It is also home to Henderson Field, an FAA emergency stop airport for transpacific flights. The island is inhabited year round by a population of ~50 residents that are a mix of FWS employees, volunteers, interns, and contractors of various nationalities. It is a tight, close-knit community where residents work, live, and spend down time together. Skills/Specialized Experience The Project Leader position at Midway Atoll NWR is one of the most unique and challenging refuge management positions in the refuge system. The ideal candidate would have experience working in remote locations, managing a large and diverse group of people, and possess an ability to maintain calm and steady leadership in the face of unexpected challenges. We are looking for a leader who will prioritize the safety, security and wellness of the island residents above all else. Other exciting challenges include complicated logistics as all supplies and personnel must be flown or shipped to the island, working with a variety of partners who rely on the island for staging (Coast Guard), monitoring (NOAA, DOD, etc...) and mission critical amenities (FAA and airport), and managing an airfield, a robust biological program, and the logistics of supporting a remote community. -

OGC-98-5 U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Resources, House of Representatives November 1997 U.S. INSULAR AREAS Application of the U.S. Constitution GAO/OGC-98-5 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Office of the General Counsel B-271897 November 7, 1997 The Honorable Don Young Chairman Committee on Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: More than 4 million U.S. citizens and nationals live in insular areas1 under the jurisdiction of the United States. The Territorial Clause of the Constitution authorizes the Congress to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property” of the United States.2 Relying on the Territorial Clause, the Congress has enacted legislation making some provisions of the Constitution explicitly applicable in the insular areas. In addition to this congressional action, courts from time to time have ruled on the application of constitutional provisions to one or more of the insular areas. You asked us to update our 1991 report to you on the applicability of provisions of the Constitution to five insular areas: Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (the CNMI), American Samoa, and Guam. You asked specifically about significant judicial and legislative developments concerning the political or tax status of these areas, as well as court decisions since our earlier report involving the applicability of constitutional provisions to these areas. We have included this information in appendix I. 1As we did in our 1991 report on this issue, Applicability of Relevant Provisions of the U.S. -

Calophyllum Inophyllum (Kamani) Clusiaceae (Syn

April 2006 Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry ver. 2.1 www.traditionaltree.org Calophyllum inophyllum (kamani) Clusiaceae (syn. Guttiferae) (mangosteen family) Alexandrian laurel, beach mahogany, beauty leaf, poon, oil nut tree (English); beach calophyllum (Papua New Guinea), biyuch (Yap); btaches (Palau); daog, daok (Guam, N. Marianas); dilo (Fiji); eet (Kosrae); feta‘u (Tonga); fetau (Samoa); isou (Pohnpei); kamani, kamanu (Hawai‘i); lueg (Marshalls); rakich (Chuuk); tamanu (Cook Islands, Society Islands, Marquesas); te itai (Kiribati) J. B. Friday and Dana Okano photo: J. B. Friday B. J. photo: Kamani trees are most commonly seen along the shoreline (Hilo, Hawai‘i). IN BRIEF Growth rate May initially grow up to 1 m (3.3 ft) in height Distribution Widely dispersed throughout the tropics, in- per year on good sites, although usually much more slowly. cluding the Hawaiian and other Pacific islands. Main agroforestry uses Mixed-species woodlot, wind- break, homegarden. Size Typically 8–20 m (25–65 ft) tall at maturity. Main products Timber, seed oil. Habitat Strand or low-elevation riverine, 0–200 m (660 ft) Yields No timber yield data available; 100 kg (220 lb) in Hawai‘i, up to 800 m (2000 ft) at the equator; mean an- nuts/tree/yr yielding 5 kg (11 lb) oil. nual temperatures 18–33°C (64–91°F); annual rainfall 1000– Intercropping Casts a heavy shade, so not suitable as an 5000 mm (40–200 in). overstory tree; has been grown successfully in mixed-species Vegetation Occurs on beach and in coastal forests. timber stands. Soils Grows best in sandy, well drained soils. -

Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘A‘Ali‘I

6 Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘a‘ali‘i OTHER COMMON NAMES: ‘a‘ali‘i kū range of habitats from dunes at sea makani, ‘a‘ali‘i kū ma kua, kū- level up through leeward and dry makani, hop bush, hopseed bush forests and to the highest peaks SCIENTIFIC NAME: Dodonaea viscosa CURRENT STATUS IN THE WILD IN HAWAI‘I: common FAMILY: Sapindaceae (soapberry family) CULTIVARS: female cultivars such as ‘Purpurea’ and ‘Saratoga’ have NATURAL SETTING/LOCATION: indigenous, been selected for good fruit color pantropical species, found on all the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho‘olawe; grows in a wide Growing your own PROPAGATION FORM: seeds; semi-hardwood cuttings or air layering for selected color forms PREPLANTING TREATMENT: step on seed capsule to release small, round, black seeds, or use heavy gloves and rub capsules vigorously between hands; put seeds in water that has been brought to a boil and removed from heat, soak for about 24 hours; if seeds start to swell, sow imme- diately; discard floating, nonviable seeds; use strong rooting hormone on cuttings TEMPERATURE: PLANTING DEPTH: sow seeds ¼" deep in tolerates dry heat; tem- after fruiting period to shape or keep medium; insert base of cutting 1–2" perature 32–90°F short; can be shaped into a small tree or maintained as a shrub, hedge, or into medium ELEVATION: 10–7700' espalier (on a trellis) GERMINATION TIME: 2–4 weeks SALT TOLERANCE: good (moderate at SPECIAL CULTURAL HINTS: male and female CUTTING ROOTING TIME: 1½–3 months higher elevations) plants are separate, although bisex- WIND RESISTANCE: -

5 (Lql"~ (T~I ~ Fl'u<Y

~-----" (t~i ~ fl'U<y 5 (lql"~ MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT AMONG THE STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE AND THE u.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL OCEAN SERVICE AND NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE FOR PROMOTING COORDINATED MANAGEMENT IN THE NORTHWESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS University Of Hawaii School of Law Library - Jon Van Dyke Archives Collection I. BACKGROUND A. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) include a vast and remote chain of islands that are a part of the Hawaiian archipelago and provide habitat to numerous species found nowhere else on earth. These islands represent a nearly pristine ecosystem where habitats upon which marine species depend include both land and water. This area represents the majority of the coral reefs found in the United States' jurisdiction and supports more than 7,000 marine species, of which half are unique to the Hawaiian Islands chain. The area is rich in history and represents a place ofciilturaI-sfgnificahcelotheHtlativeHawaiians:lt is an-area that must be carefully managed to ensure that the resources are not diminished for future generations. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are also the most remote archipelago in the world. This isolation has resulted in need for integrated resource management of this vast and exceptional marine environment. There is a need for coordinated management in this unique and special pl~ce where various State and Federal agencies and advisory councils have a variety of authorities and jurisdiction. B. The area subject to this Agreement is the lands and waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands out to 50 nautical miles and includes all atolls, reefs, shoals, banks, and islands from Nihoa Island in the Southeast to Kure Atoll in the Northwest. -

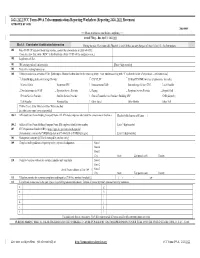

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (Reporting 2020 2021 Revenues) APPROVED BY OMB 3060-0855 >>> Please read instructions before completing.<<< Annual Filing -- due April 1, 20212022 Block 1: Contributor Identification Information During the year, filers must refile Blocks 1, 2 and 6 if there are any changes in Lines 104 or 112. See Instructions. 101 Filer 499 ID [If you don't know your number, contact the administrator at (888) 641-8722. If you are a new filer, write “NEW” in this block and a Filer 499 ID will be assigned to you.] 102 Legal name of filer 103 IRS employer identification number [Enter 9 digit number] 104 Name filer is doing business as 105 Telecommunications activities of filer [Select up to 5 boxes that best describe the reporting entity. Enter numbers starting with “1” to show the order of importance -- see instructions.] Audio Bridging (teleconferencing) Provider CAP/CLEC Cellular/PCS/SMR (wireless telephony inc. by resale) Coaxial Cable Incumbent LEC Interconnected VoIP Interexchange Carrier (IXC) Local Reseller Non-Interconnected VoIP Operator Service Provider Paging Payphone Service Provider Prepaid Card Private Service Provider Satellite Service Provider Shared-Tenant Service Provider / Building LEC SMR (dispatch) Toll Reseller Wireless Data Other Local Other Mobile Other Toll If Other Local, Other Mobile or Other Toll is checked describe carrier type / services provided: 106.1 Affiliated Filers Name/Holding Company Name (All affiliated companies must show the same -

Photographing the Islands of Hawaii

Molokai Sea Cliffs - Molokai, Hawaii Photographing the Islands of Hawaii by E.J. Peiker Introduction to the Hawaiian Islands The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight primary islands and many atolls that extend for 1600 miles in the central Pacific Ocean. The larger and inhabited islands are what we commonly refer to as Hawaii, the 50 th State of the United States of America. The main islands, from east to west, are comprised of the Island of Hawaii (also known as the Big Island), Maui, Kahoolawe, Molokai, Lanai, Oahu, Kauai, and Niihau. Beyond Niihau to the west lie the atolls beginning with Kaula and extending to Kure Atoll in the west. Kure Atoll is the last place on Earth to change days and the last place on Earth to ring in the new year. The islands of Oahu, Maui, Kauai and Hawaii (Big Island) are the most visited and developed with infrastructure equivalent to much of the civilized world. Molokai and Lanai have very limited accommodation options and infrastructure and have far fewer people. All six of these islands offer an abundance of photographic possibilities. Kahoolawe and Niihau are essentially off-limits. Kahoolawe was a Navy bombing range until recent years and has lots of unexploded ordinance. It is possible to go there as part of a restoration mission but one cannot go there as a photo destination. Niihau is reserved for the very few people of 100% Hawaiian origin and cannot be visited for photography if at all. Neither have any infrastructure. Kahoolawe is photographable from a distance from the southern shores of Maui and Niihau can be seen from the southwestern part of Kauai. -

B: Other U.S. Island Possessions in the Tropical Pacific

Appendix B Other U.S. Island Possessions in the Tropical Pacific1 Introduction Howland, Jarvis, and Baker Islands There are eight isolated and unincorporated is- Howland, Jarvis and Baker are arid coral islands lands and reefs under U.S. control and sovereignty in the southern Line Island group (figure B-l). Aside in the tropical Pacific Basin. Included in this cate- from American Samoa, Jarvis Island is the only gory are: Kingman Reef, Palmyra and Johnston other U.S.-affiliated island in the Southern Hemi- Atolls in the northern Line Island group; Howland, sphere. These islands lie within one-half degree Baker and Jarvis Islands in the southern Line Is- from the equator, in the equatorial climatic zone. land group; Midway Atoll at the northwest end of During the 19th century the United States and the Hawaiian archipelago; and Wake Island north Britain actively exploited the significant guano de- of the Marshall Islands. Evidence indicates that posits found on these three islands. Jarvis Island some of these islands were not inhabited prior to was claimed by the United States in 1857, and sub- “Western” discovery; and today some remain unin- sequently annexed by Britain in 1889. Jarvis, Howland, habited. and Baker Islands were made territories of the These islands range from less than 1 degree south United States in 1936, and placed under the juris- latitude to nearly 29 degrees north latitude and from diction of the Department of the Interior. The is- 162 degrees west to 167 east longitude. The climate lands currently are uninhabited. regimes range from arid to wet and equatorial to These atolls were used as weather stations and subtropical. -

LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria Immutabilis

Alaska Seabird Information Series LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria immutabilis Conservation Status ALASKA: High N. AMERICAN: High Concern GLOBAL: Vulnerable Breed Eggs Incubation Fledge Nest Feeding Behavior Diet Nov-July 1 ~ 65 d 165 d ground scrape surface dip fish, squid, fish eggs and waste Life History and Distribution Laysan Albatrosses (Phoebastria immutabilis) breed primarily in the Hawaiian Islands, but they inhabit Alaskan waters during the summer months to feed. They are the 6 most abundant of the three albatross species that visit 200 en Alaska. l The albatross has been described as the “true nomad ff Pok e of the oceans.” Once fledged, it remains at sea for three to J ht ig five years before returning to the island where it was born. r When birds are eight or nine years old they begin to breed. y The breeding season is November to July and the rest of Cop the year, the birds remain at sea. Strong, effortless flight is commonly seen in the southern Bering Sea, Aleutian the key to being able to spend so much time in the air. The Islands, and the northwestern Gulf of Alaska. albatross takes advantage of air currents just above the Nonbreeders may remain in Alaska throughout the year ocean's waves to soar in perpetual fluid motion. It may not and breeding birds are known to travel from Hawaii to flap its wings for hours, or even for days. The aerial Alaska in search of food for their young. Albatrosses master never touches land outside the breeding season, but have the ability to concentrate the food they catch and it does rest on the water to feed and sleep. -

A Review of Recent Developmenets in Ocean and Coastal Law 2001-2002 Karla Black University of Maine School of Law

Ocean and Coastal Law Journal Volume 7 | Number 2 Article 6 January 2002 A Review Of Recent Developmenets In Ocean And Coastal Law 2001-2002 Karla Black University of Maine School of Law Denis Culley University of Maine School of Law Jeffrey Dolley University of Maine School of Law Gregory Domareki University of Maine School of Law Sara Edmonds University of Maine School of Law See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Karla Black, Denis Culley, Jeffrey Dolley, Gregory Domareki, Sara Edmonds, Kevin Fitzgerald, Rody Fowles, Michael Fuller, John Hatch, Katherin Joyce, Sean Kerwin, Jacqueline Lewy, Daniel Marra, Sarah McCready, John M. Ney, Jr., Chad Olcott, Mary Saunders, Vanessa Tondini, David Walker & Danielle West-Chuhta, A Review Of Recent Developmenets In Ocean And Coastal Law 2001-2002, 7 Ocean & Coastal L.J. (2002). Available at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj/vol7/iss2/6 This Recent Developments is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ocean and Coastal Law Journal by an authorized editor of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Review Of Recent Developmenets In Ocean And Coastal Law 2001-2002 Authors Karla Black; Denis Culley; Jeffrey Dolley; Gregory Domareki; Sara Edmonds; Kevin Fitzgerald; Rody Fowles; Michael Fuller; John Hatch; Katherin Joyce; Sean Kerwin; Jacqueline Lewy; Daniel Marra; Sarah McCready; John M. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

A Case Study of Threatened Boraginales J Ames S

Assessing the effectiveness of Madagascar’s changing protected areas system: a case study of threatened Boraginales J ames S. Miller and H olly A. Porter Morgan Appendix Provisional assignment of species of Malagasy Cordia subcordata Lam. (LC). Native, non-endemic, wide- Boraginales to IUCN Red List categories (see also Tables 1 & spread in the Old World from Africa through to tropical 2), with criteria (IUCN, 2001) and detailed comments. Asia and the Pacific to Hawaii. Varronia curassavica Jacq. (NE). Introduced and poten- Cordiaceae tially invasive. Coldenia procumbens L. (LC). Infrequently collected in western Madagascar but it is weedy and probably underrep- Ehretiaceae resented in collections. Furthermore, it is widespread in the Old World through Africa and tropical Asia to Australia. Ehretia australis J.S. Mill. (EN) B1b(i,ii,iii)2ab(i,ii,iii). Na- tive, endemic, with both EOO and AOO below the Cordia africana Lam. (NE). Introduced and cultivated. threshold for Endangered and occurring in habitats that Cordia caffra Sond. (LC). Widespread in dry forests of are under extreme threat. southern Madagascar and also occurs in South Africa: Ehretia cymosa Thonn. (LC). Native, non-endemic, wide- globally it is not threatened even though its Malagasy spread and common in Madagascar and also known from populations have an AOO below the threshold for large areas in Africa and the Mascarene Islands. Endangered. Ehretia decaryi J.S. Mill. (EN) B1b(i,ii,iii)2ab(i,ii,iii). Native, Cordia dentata Poir. (NE). Introduced and cultivated. endemic, with both EOO and AOO below the threshold for Cordia lowryana J.S. Mill.