DARE to KNOW Chess in the Age of Reason

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

150520 WCHOF Press Kitupdated

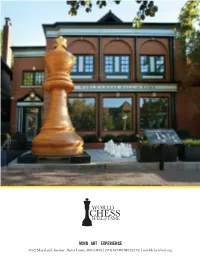

MIND • ART • EXPERIENCE 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314)367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org ABOUT THE WORLD CHESS HALL OF FAME The World Chess Hall of Fame creates engaging exhibitions celebrating the game of chess, its history, and its impact on art and culture. Through these exhibitions and innovative educational programming, the WCHOF hopes to popularize chess among a new and diverse audience. The WCHOF also seeks to serve as a repository for artifacts related to the rich history of the game of chess. MISSION The mission of the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) is to educate visitors, fans, players, and scholars by preserving, exhibiting, and interpreting the game of chess and its continuing cultural and artistic significance. HISTORY & IMPACT The World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) was created in 1986 by the United States Chess Federation in New Windsor, New York. Originally known as the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, the small museum contained a modest collection that included a book of chess openings signed by Bobby Fischer, the Paul Morphy silver set, and plaques honoring past grandmasters. The institution and its contents moved twice during the 1990s and early 2000s, first to Washington, D.C., and then to Miami. It found a permanent home in 2011 when it was decided to relocate to Saint Louis’ Central West End neighborhood due to the city’s renown as international center for the game. The World Chess Hall of Fame has an outstanding reputation for its displays of artifacts from the permanent collection as well as temporary exhibitions highlighting the great players, historic matches, and rich cultural history of chess. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Warrior-Bishops In

WARRIOR-BISHOPSIN LA CHANSON DE ROLAND AND POWA DE MI0 CID EARL R. ANDERSON ARCHBISHOP TURPIN, THE fighting bishop in La Chanson de Roland, is a character whose behavior and attitudes are contrary to modem assumptions about what a medieval clergyman should have been. The poet's first mention of him, it is true, represents him in a role that is consistent with conventional views about the clergy: he volunteers to travel to Marsilion's court as Charlemagne's peace ambassador (264-73)-but so do the barons Naimon, Roland, and Olivier (246-58). In each subsequent appearance in the poem, however, Brpin accompanies the Frankish rearguard not as a peaceable messenger of the Prince of Peace but more and more as one of Charlemagne's most ferocious warriors. In his "sermun" at Roncevaux, he admonishes the Franks to fight, "Chrestientet aidez a sustenir" '[to] help to sustain the Christian faith' (1129), and "Clamez vos culpes, si preiez Deumercit" 'confess your sins, and pray to God for mercy' (1132), and he promises absolution for sins in exchange for military service, and martyrdom in exchange for death on the battlefield (1134-38). He rides to battle on a horse once owned by Grossaille, a king whom he had killed in Denmark (1488-89). During the course of battle, Tbrpin kills the Berber Corsablix, the enchanter Siglorel, the African Malquiant, the infernally-named Saracen Abisme, and four hundred others, elsewhere striking a War, Literature, and the Arts thousand blows (1235-60, 1390-95, 1414, 1470-1509, 1593-1612, 2091-98). lbrpin and Roland are the last of the Franks to die in the battle. -

The Enlightenment A. Voltaire

MWH Unit 3: Revolutions Primary Sources: The Enlightenment A. Voltaire “Philosophical Dictionary: The English Model” 1764 The English constitution has, in fact, arrived at that point of excellence, in consequence of which all men are restored to those natural rights, which, in nearly all monarchies, they are deprived of. Those rights are, entire liberty of person and property; freedom of the press; the right of being tried in all criminal cases by a jury of independent men—the right of being tried only according to the strict letter of the law; and the right of every man to profess, unmolested, what religion he chooses, while he renounces offices, which the members of the Anglican or established church can hold. These are denominated privileges. And, in truth, invaluable privileges they are in comparison with the usages of most other nations of the world! What social, cultural or political issue is the author explicitly or implicitly addressing in the passage? What solution does he or she present? Has the solution brought the intended results by 2015? B. Immanuel Kant “ What is Enlightenment?” 1784 Enlightenment is man’s leaving his self-caused immaturity. Immaturity is the incapacity to use one’s intelligence without the guidance of another. Such immaturity is self-caused if it is not caused by lack of intelligence, but by lack of determination and courage to use one’s intelligence without being guided by another. Sapere Aude! Have the courage to use your own intelligence! is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment. What social, cultural or political issue is the author explicitly or implicitly addressing in the passage? What solution does he or she present? Has the solution brought the intended results by 2015? C. -

THE BATTLE CRY Greater Greenville Hockey Association V1516.2

October 2015 THE BATTLE CRY Greater Greenville Hockey Association V1516.2 In this issue: How to Dress Your Youth Dressing Your Player Hockey Player for Practice Road Tripping Golf Scramble If Itech, Bauer, or CCM sound foreign to you, feel Travel Team Updates comforted by the fact that you are not alone. Now Pictures from the Road that you have an GGHA Hockey player, these House Updates names will become as familiar to you as your pet's Calendars/Contacts name. Over half a million youth play hockey in the United States each year and all of their parents had to learn the art of clipping, taping and tying hockey gear. Your child may be envisioning the Stanley Cup but you are probably envisioning the dent in your checkbook. Outfitting your child for hockey does not have to be a huge expense and there are fewer things cuter than your 5 year old dressed up in full hockey gear! Tips for saving on gear. #1—GGHA Hockey swap! Happens in August. Plan on it. Find used gear for CHEAP! 2. Second hand. One person’s gently used goods are another person’s treasure, especially when it comes to hockey. However, for safety reasons, it is important to use strict caution when purchasing sec- ond-hand gear, USA Hockey standards. 3. Purchase last year’s models. Best time is in late July or early August. 4. If you know family or friends who are involved in hockey, ask if they have equipment they no longer use. This is especially useful if younger kids have outgrown their lightly used gear 5. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

A Glimpse Into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Media Contact: Amanda Cook [email protected] 314-598-0544 A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015 July XX, 2014 (Saint Louis, MO) – From his earliest years as a child prodigy to becoming the only player ever to achieve a perfect score in the U.S. Chess Championships, from winning the World Championship in 1972 against Boris Spassky to living out a controversial retirement, Bobby Fischer stands as one of chess’s most complicated and compelling figures. A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer opens July 24, 2014, at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and will celebrate Fischer’s incredible career while examining his singular intellect. The show runs through June 7, 2015. “We are thrilled to showcase many never-before-seen artifacts that capture Fischer’s career in a unique way. Those who study chess will have the rare opportunity to learn from his notes and books while casual fans will enjoy exploring this superstar’s personal story,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Bobby Fischer, seen from above, Shannon Bailey. makes a move during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Several of the rarest pieces on display are on generous loan from Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, owners of a a collection of material from Fischer’s own library that includes 320 books and 400 periodicals. These items supplement highlights from WCHOF’s permanent collection to create a spectacular show. Highlights from the exhibition: Furniture from the home of Fischer’s mentor Jack Collins, which -

Media Contact: Brian Flowers (314) 243-1571 [email protected]

Media Contact: Brian Flowers (314) 243-1571 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibition Celebrates the Legacy of World-Renowned Artist Keith Haring The exhibition is the largest, solo collection of Haring’s work ever shown in Saint Louis SAINT LOUIS (November 13, 2020) - The World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) will host an opening reception for its newest exhibition, Keith Haring: Radiant Gambit, celebrating the legacy of world-renowned artist Keith Haring, on November 19, 2020, from 5:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. The reception will include bottled cocktails by Brennan’s on the WCHOF outdoor chess patio, timed curator-led tours of all three exhibitions and a virtual tour on the museum’s website, Facebook and YouTube channels. Keith Haring: Radiant Gambit features artwork by Haring, a world-renowned artist known for his art that proliferated in the New York subway system during the early 1980s. The exhibition includes a never-before-seen private collection of Haring’s works and photographs of the artist, bespoke street art chess sets from Purling London and newly- commissioned pieces by Saint Louis artists, all paying homage to the late icon. “The World Chess Hall of Fame is honored to present the art of Keith Haring in this exhibition, which includes work spanning the entirety of his career,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Shannon Bailey. “Haring’s influence, even though he passed away over 30 years ago, is still prevalent to this day. He believed art was for everybody, just as the World Chess Hall of Fame believes chess is for everybody.” The two-floor exhibition will feature 130 works, including a never-before-seen private collection of Keith Haring’s work via Pan Art Connections, Inc., loans from the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in Saint Louis and photographs of Haring by Allan Tannebaum. -

M938s6 1913.Pdf

.- . -_ = WHAT THE WORKERS SAY OF SONGS OF SOCIALISM “Comrade Moyer is the Socialist Missing Link.‘S. Smith. “The greatest thing that has happened-to the Socialist Party.“- Nina E. Woods. “It is bound to be a success as a popular work.“--Gaylord Wilshire. “I am sure they will have a stirring and needed effect on the Socialist movement.“-&oroe D. Herron. “Quite a contrast to the other reform literature and poetry I get more or less of. A Capital idea to use the old familiar tunes.“-X. 0. Nelson. “We need the stirring and inspiring influence of music in the propa- ganda of Socialism and your efforts in this direction are most com- mendabie.“-Ezlgene V. Webs. “I am fully persuaded that ‘Songs of Socialism’ will play no mean part in awakening and stirring to action the sons and daughters of toil, for the emancipatron of mankind.“-]. &iahlolz Barnes. “You have produced just what the Socialists have been waiting for- a pieading for our cause in worthy words of song-without bitterness, without hate, only sweetness and hope. Wit, good sense, and inspiration to all who sing them are the marked features of these popular Socialist Songs.“-4Valter Thomas Mills, Artfhor of The Struggle for Existence. “Songs of Socialism” is by all odds the best thing that has yet appeared in the form of Socialist songs. It is a happy blending of senti- ment adapted to the practical, heaven-on-earth idea that is the result of modern thinking and scientnic investigation.-Chicago Socialisi. .“I- congratulate you on your new ‘Songs of Socialism.’ The collec- tion is the most inspiring and satisfying of any f have vet seen. -

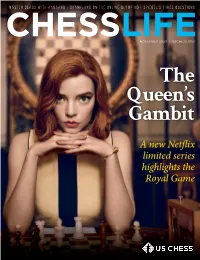

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Immanuel Kant: What Is Enlightenment?, 1784

Immanuel Kant: What is Enlightenment?, 1784 Was ist Äufklarung? Enlightenment is man's release from his self-incurred tutelage. Tutelage s man's inability to make use of his understanding without direction from another. Self- incurred is this tutelage when its cause lies not in lack of reason but in lack of resolution and courage to use it without direction from another. Sapere aude! "Have courage to use your own reason!"- that is the motto of enlightenment. Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why so great a portion of mankind, after nature has long since discharged them from external direction (naturaliter maiorennes), nevertheless remains under lifelong tutelage, and why it is so easy for others to set themselves up as their guardians. It is so easy not to be of age. If I have a book which understands for me, a pastor who has a conscience for me, a physician who decides my diet, and so forth, I need not trouble myself. I need not think, if I can only pay - others will easily undertake the irksome work for me. That the step to competence is held to be very dangerous by the far greater portion of mankind (and by the entire fair sex) - quite apart from its being arduous is seen to by those guardians who have so kindly assumed superintendence over them. After the guardians have first made their domestic cattle dumb and have made sure that these placid creatures will not dare take a single step without the harness of the cart to which they are tethered, the guardians then show them the danger which threatens if they try to go alone. -

Kant's Ostensible Anti-Thesis of "Public" and "Private" and the Subversion of the Language of Authority

KANT's OSTENSIBLE ANTITHESIS OF "PUBLIC" AND "PRIVATE" AND THE SUBVERSION OF THE LANGUAGE OF AUTHORITY IN U AN ANSWER TO THE QUESTION: .IWHAT Is ENLIGHTENMENT?'" Michael D. Royal Wheaton College 1 In U An Answer to the Question: 'What Is Enlightenment?'," writtenin1784, Kant brought to the table of philosophical discourse what previously had been merely a political concern -the manner in which enlightenment ought to proceed (Schmidt, "The Question" 270). His essay was one of tw02 historically significant responses to Protestant clergyman Johann Friedrich Zollner's query, posed in a footnote of an essay in the Berlinische Monatsschrif. "Whatis enlight enment? This question, which is almost as important as [the ques tion] What is truth? would seem to require an answer, before one engages in enlightening other people... ./1 (qtd. in Bahr 1-2). The topic of social enlightenment was widely debated as Europe searched· for a scientific identity, one which Kant was willing to supplywithwhathecalledhis own "Copernicanrevolution." Kant's line of reasoning in "What Is Enlightenment?/I is different and more compelling than those of his contemporaries in that Kant not only proposes bothdefinitionofandmethodforenlightenment, butconjoins the two in an intimate relationship, the essential link between them being free speech, but (as we will see) a qualified kind of free speech termed Ifthe public use of reason./I Consequently, Kant's argument is political in its aim but philosophical in its approach, appealing to the nature of the polis itself, the nature of historical progress, and the nature of reason. As such, its implications are deep and far-reaching.