Evolution of Game-Play in the Australian Football League from 2001 to 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your Guide to Corporate Suites and Experiences in 2018/19

Premium Experiences Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your guide to corporate suites and experiences in 2018/19. An Australian icon The Melbourne Cricket Ground was built in 1853 and since then, has established a marvellous history that compares favourably with any of the greatest sporting arenas in the world. Fondly referred to as the ‘G, Australia’s favourite stadium has hosted Olympic and Commonwealth Games, is the birthplace of Test Cricket and the home of Australian Rules Football. Holding more than 80 events annually and attracting close to four million people, the MCG has hosted more than 100 Test matches (including the first in 1877) and is home to a blockbuster events calendar including the traditional Boxing Day Test and the AFL Grand Final. MCG EST. 1853 EST. MCG THE PINNACLE OF TEST CRICKET AND THE HOME OF AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL CORPORATE SUITE LEASING Many of Australia’s leading businesses choose to entertain their clients and staff in the unique and relaxed environment of their very own corporate suite at the iconic MCG. CORPORATE SUITE LEASING 2018/19 CORPORATE Designed to offer first-class amenities, personal service and an exclusive environment, an MCG corporate suite is the perfect setting to entertain, reward employees or enjoy an event with friends in capacities ranging from 10-20 guests. Corporate suite holders are guaranteed access to all AFL home and away matches scheduled at the MCG, AFL Finals series matches including the AFL Grand Final, and international cricket matches at the MCG, headlined by the renowned Boxing Day Test. You will also enjoy; - Two VIP underground car park passes - Company branding facing the ground - Two additional suite entry tickets to all events - Non-match day access for business meetings THE YEAR AWAITS There are plenty of exciting events to look forward to at the MCG in 2018, headlined by the AFL Grand Final, and the Boxing Day Test. -

Club and AFL Members Received Free Entry to NAB Challenge Matches and Ticket Prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series Were Held at 2013 Levels

COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS DARREN BIRCH GENERAL MANAGER Club and AFL members received free entry to NAB Challenge matches and ticket prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series were held at 2013 levels. eason 2015 was all about the with NAB and its continued support fans, with the AFL striving of the AFL’s talent pathway. to improve the affordability The AFL welcomed four new of attending matches and corporate partners in CrownBet, enhancing the fan experience Woolworths, McDonald’s and 2XU to at games. further strengthen the AFL’s ongoing SFor the first time in more than 10 development of commercial operations. years, AFL and club members received AFL club membership continued free general admission entry into NAB to break records by reaching a total of Challenge matches in which their team 836,136 members nationally, a growth was competing, while the price of base of 3.93 per cent on 2014. general admission tickets during the In season 2015, the Marketing and Toyota Premiership Season remained the Research Insights team moved within the same level as 2014. Commercial Operations team, ensuring PRIDE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Fans attending the Toyota AFL Finals greater integration across membership, The Showdown rivalry between Eddie Betts’ Series and Grand Final were also greeted to ticketing and corporate partners. The Adelaide Crows and Port ticket prices at the same level as 2013, after a Research Insights team undertook more Adelaide continued in 2015, price freeze for the second consecutive year. than 60 projects, allowing fans, via the with the round 16 clash drawing a record crowd NAB AFL Auskick celebrated 20 years, ‘Fan Focus’ panel, to influence future of 53,518. -

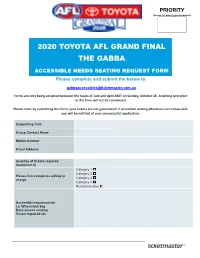

2020 TOYOTA AFL GRAND FINAL the GABBA ACCESSIBLE NEEDS SEATING REQUEST FORM Please Complete and Submit the Below To

PRIORITY (please list priority group number) 2020 TOYOTA AFL GRAND FINAL THE GABBA ACCESSIBLE NEEDS SEATING REQUEST FORM Please complete and submit the below to [email protected] Forms are only being accepted between the hours of 7am and 4pm AEST on Sunday, October 18. Anything sent prior to this time will not be considered. Please note: by submitting this form, your tickets are not guaranteed. If accessible seating allocations are exhausted, you will be notified of your unsuccessful application. Supporting Club Group Contact Name Mobile Number Email Address Quantity of tickets required (maximum 6) Category 1 ☐ Category 2 ☐ Please tick categories willing to Category 3 ☐ accept Category 4 ☐ Restricted View ☐ Accessible requirements: i.e. Wheelchair bay Easy access seating Vision impaired etc. It is a requirement from Queensland Health to provide the information for all members for contact tracing purposes. Please complete the information below for all members who you are wanting to attend the 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final with. Member #1 Priority Group ☐ Priority 1 ☐ Priority 2 ☐ Priority 3 Member Name Mobile phone number Email address Membership barcode number Companion card number (if applicable) ☐ You acknowledge that you are not entering The Gabba from a known banned area, hotspot or currently serving a mandated 14 day quarantine period & you accept the AFL’s acknowledgement of risk. To be able to book your tickets, please tick the box. Member #2 Priority Group ☐ Priority 1 ☐ Priority 2 ☐ Priority 3 Member Name Mobile phone number Email address Membership barcode number Companion card number (if applicable) ☐ You acknowledge that you are not entering The Gabba from a known banned area, hotspot or currently serving a mandated 14 day quarantine period & you accept the AFL’s acknowledgement of risk. -

The Media's Impact on Play in the Australian Football League

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT. STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.2478/pcssr-2018-0001 Managed Play: The Media’s Impact on Play in the Australian Football League Authors’ contribution: Samuel Keith Duncan A) conception and design of the study B) acquisition of data Holmesglen Institute, Australia, Victoria C) analysis and interpretation of data D) manuscript preparation E) obtaining funding ABSTRACT No industry has influenced the transformation of the Australian Football League (AFL) into a professional, commercial business more than the media. Today, the AFL players are paid more than ever and are used as marketing tools to promote and sell the game, often to new fans in new markets of Australia – namely New South Wales and Queensland - who haven’t traditionally played Australian Football, preferring the rugby codes instead. But perhaps the biggest change in the AFL is that the play element is now used as function of business. Put simply, winning leads to more money. As such, the play element is now manipulated more than ever. The game has more coaches implementing more tactics, strategies, game plans and set plays than ever before. These changes can be linked back to the media’s influence on the game. This paper utilises the combined observations and theories of Johan Huizinga and Pierre Bourdieu to create a theoretical lens through which we can understand the media’s growing influence in sport and its impact on play’s transformation. The theory will then be expounded through an extensive analysis of the media’s influence in the AFL, particularly its play element. This analysis will be supported with insights and views from AFL fans, members, commentators and theorists. -

A'court, BILL (West Adelaide)

A A’COURT, BILL (West Adelaide): Acourt was placed on Oliver and to keep this man from taking his sensational marks gives a man plenty to do. Acourt did not let him do too much, and played a good game beside.1 Father of star West Adelaide ruckman of the 1950s Fred A’Court (profiled below), Bill A’Court was a strong defender who also played with West. He debuted with the club in 1909, and was a key member that same year of its winning grand final team against Port Adelaide. He went on to play in the premiership sides of 1911 and 1912 as well. From 1909 to 1915 A’Court played 83 SAFL games and kicked four goals. A’COURT, FRED (West Adelaide): Fred A’Court was a stalwart of West Adelaide sides during the club’s nightmare decade of the 1950s, when four grand finals were contested without success, all against Port Adelaide. He commenced with West in 1949, and over the ensuing 11 seasons played a total of 159 league games and kicked 110 goals. In January 1954, A’Court applied for a clearance to VFL club Richmond, claiming that, if he made the move, he would be £15 a week better off financially, but West Adelaide refused the application and he continued to play for the Blood and Tars for the remainder of his career. A tough, tireless and talented ruckman, A’Court - popularly known as ‘Boof’ - represented South Australia eight times, kicking 10 goals. AAMODT, COLIN (North Adelaide): In a brainy display of football Aamodt showed all the fleetness of foot that enabled him to run a place in a Stawell Gift. -

1583378583-2020-Afl-Fixture.Pdf

2020 TOYOTA AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON ROUND 1 ROUND 7 ROUND 13 ROUND 19 Thursday, March 19 Friday, May 1 Thursday, June 11 Friday, July 24 Richmond vs. Carlton (MCG) (N) Collingwood vs. St Kilda (MRVL) (N) West Coast Eagles vs. Essendon (OS) (N) Port Adelaide vs. Hawthorn (AO) (N) Friday, March 20 Saturday, May 2 Friday, June 12 Saturday, July 25 Western Bulldogs vs. Collingwood (MRVL) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Adelaide Crows (MS) Hawthorn vs. Geelong Cats (MCG) (N) Carlton vs. West Coast Eagles (MCG) Saturday, March 21 Richmond vs. GWS GIANTS (MCG) Saturday, June 13 North Melbourne vs. Gold Coast SUNS (BA) Essendon vs. Fremantle (MRVL) Port Adelaide vs. Carlton (AO) (T) North Melbourne vs. Brisbane Lions (BA) Geelong Cats vs. Melbourne (GMHBA) (T) Adelaide Crows vs. Sydney Swans (AO) (T) Geelong Cats vs. Brisbane Lions (GMHBA) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. St Kilda (TIO) (T) GWS GIANTS vs. Sydney Swans (GS) (T) GWS GIANTS vs. Geelong Cats (GS) (N) Western Bulldogs vs. Hawthorn (MRVL) (N) Western Bulldogs vs. GWS GIANTS (MRVL) (N) Essendon vs. Adelaide Crows (MRVL) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Port Adelaide (MS) (N) Sunday, May 3 Sunday, June 14 Sunday, July 26 Adelaide Crows vs. Port Adelaide (AO) Sunday, March 22 Sydney Swans vs. North Melbourne (SCG) Richmond vs. Western Bulldogs (MCG) North Melbourne vs. St Kilda (MRVL) Byes: Carlton, Collingwood, Fremantle, Essendon vs. Melbourne (MCG) Brisbane Lions vs. St Kilda (G) Hawthorn vs. Brisbane Lions (MCG) West Coast Eagles vs. Fremantle (OS) (T) Melbourne, Richmond, Sydney Swans West Coast Eagles vs. Melbourne (OS) (T) Fremantle vs. -

Seven Secures Long-Term Partnership with the Australian Football League

Seven secures long-term partnership with the Australian Football League Seven signs new six year agreement for seasons 2017-2022 Seven signs all-encompassing agreement for broadcast television for Thursday Night Football, Friday Night Football, Saturday Night Football and Sunday Afternoon Football Seven secures AFL Finals Series, AFL Grand Final and Brownlow Medal and all major holiday “blockbuster” matches. 18 August 2015 --- The Seven Network, Australia’s most-watched broadcast television platform and a key business of Seven West Media, one of Australia’s leading integrated media and content creation companies, today confirmed the signing of an historic, long-term agreement for an all-encompassing coverage of the Australian Football League for seasons 2017-2022. The new agreement builds on Seven’s current agreement with the AFL for the 2012-2016 football seasons. Kerry Stokes, Chairman of Seven West Media, said: “Seven and the Australian Football League have a long-standing and deep connection. We are delighted to confirm our partnership with the AFL and look forward to working closely with them as we expand our coverage over the coming decade. “The signing of this agreement forms a key part of our company’s plans for development and underlines our commitment to the future of broadcast television as we build our media presence over the coming decade.” Seven’s agreement with the Australian Football League delivers free broadcast television for Thursday Night Football, Friday Night Football, Saturday Night Football and Sunday Afternoon Football. Seven has also secured the Australian Football League Finals Series and Grand Final along with the Brownlow Medal. -

September Issue

THURSDAY SEPTEMBER 3 2020 SPORT 43 Gabba final big boost to AFL in QLD Historic night for GF BRISBANE Lions captain Dayne Zorko says an AFL SAM LANDSBERGER Grand Final at the Gabba is the ideal platform to entice more THE AFL’s decision to Queensland juniors to play stage a historic night Grand Aussie rules. Final in Brisbane on Octo- With the Gabba expected to ber 24 could pave the way be confirmed as the venue for for a spectacular event this year’s AFL decider, Zorko under lights at the MCG predicted a surge in interest in next year. the sport in a rugby league- The league confirmed dominated state. footy’s worst-kept secret on “When I was a kid coming Wednesday when the up at school, I would have been Gabba was locked in to one of maybe four in the entire host the blockbuster as a school that played AFL (or) thank you to the Queens- that even followed AFL,” land government for saving Zorko told SEN. the season. “Now the fact that the city It will be the first time in of Brisbane will get the Grand VFL-AFL history the Final, I think there’s a real op- Grand Final has been portunity to grow the game staged outside of Victoria significantly up here. or at night. “My little fella’s going to hit The league is still to lock school next year, and I’m hop- in the starting time but AFL ing by the time he finishes boss Gillon McLachlan said school, he’s not the only one the first bounce will be at playing AFL and there’s about 6.30pm (5.30pm Queens- a couple of hundred that are land time) at the earliest. -

GEMBA | Sport & Entertainment Insights

Use Crop and rotate image when necessary COVID-19 and sport – latest Australian insights SPORT & ENTERTAINMENT INSIGHTS 20 AUGUST 2020 IF IT CAN’T BE HELD AT THE MCG, AFL FANS HAVE GIVEN THE GABBA IN BRISBANE THEIR BLESSING AS PREFERRED HOST FOR THE 2020 GRAND FINAL. BUT STATE-BASED PAROCHIALISM FOR A “HOME” FINAL REMAINS STRONG. MEANWHILE, THERE ARE STILL MIXED OPINIONS ON THE SUCCESS OF ARTIFICIAL CROWD NOISE IN LIVE SPORT BROADCASTS. AND OVER A THIRD OF AUSTRALIAN SPORTS FANATICS ARE SHOWING SIGNS OF DISCONNECTING FROM SPORT DURING COVID – PRESENTING A CHALLENGE AND OPPORTUNITY TO RE- ENGAGE THEM LEADING INTO 2021. GEMBA© 2020 2 With the 2020 AFL Grand Final unlikely to be played at the MCG, the Gabba has fans’ blessing as the preferred host PREFERRED LOCATION FOR THE 2020 AFL GRAND FINAL (IF NOT MCG) AFL Fanatics (national average) Victorians Brisbane: The Gabba 33% 42% Perth: Optus Stadium 28% 26% Adelaide: Adelaide Oval 20% 14% Sydney: ANZ Stadium 18% 19% Q - If the AFL Grand Final is not to be held at the MCG in Melbourne due to COVID, where would you prefer it to be played instead? GEMBA© 2020 3 But on a state by state basis, South Australians are the most parochial, with 84% calling for the Adelaide Oval to host the Grand Final PREFERRED LOCATION FOR THE 2020 AFL GRAND FINAL (IF NOT MCG) | BY STATE Western South Victoria NSW/ACT Queensland Australia Australia Brisbane: The Gabba 42% 72% Perth: Optus Stadium 64% Adelaide: Adelaide Oval 84% Sydney: ANZ Stadium 57% Q - If the AFL Grand Final is not to be held at the MCG in Melbourne -

Important Information Related to Covid-19

IMPORTANT INFORMATION RELATED TO COVID-19 During your attendance at the 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final, you must comply with any direction given by the AFL (or AFLEO on behalf of the AFL) and the venue, including in relation to social distancing requirements, and any direction or guidance given by the government, including any and all directions of the Queensland Government Chief Health Officer’s under section 362B of the Public Health Act 2005 (Qld), in relation to the current COVID-19 outbreak. Notwithstanding any other provision of these terms and conditions, should the 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final be cancelled due to COVID-19, you will receive a refund of payment made to AFLEO for your package. Should crowd numbers at the 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final need to be reduced for any reason, including due to a Queensland State Government adjustment to COVID-19 social distancing restrictions, any 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final package purchase may be subject to either a reduction in quantity or full cancellation. Any customer who has their package either reduced or cancelled will receive a refund proportionate to their reduced package numbers, or in the event of cancellation a full refund for the that package. Individual name, mobile number and email (or address where individual does not have an email account) will be required for all patrons purchasing The Verandah, Premiers Lounge, The Ultimate, Before the Bounce and the Grand Final Series Pass. Please be prepared with this information before proceeding with a booking. You will not be able to complete your booking without providing this information. -

Deal Done on Mcg Grand Final Contract Extension

Wednesday, 2 September 2020 DEAL DONE ON MCG GRAND FINAL CONTRACT EXTENSION The Victorian Government has agreed to the relocation of the AFL Grand Final from the home of football – the MCG – to Brisbane for one year, with that year to be added to the MCG’s decades-long Grand Final contract. The 2020 AFL Grand Final will be played at the Gabba on Saturday, 24 October with the AFL agreeing to schedule a start time that does not clash with the 100th running of the WS Cox Plate at Moonee Valley. The coronavirus pandemic means it is impossible to plan with certainty for an event to be held with crowds in Melbourne in late October. Accepting this situation, the Victorian Government acted to ensure that football’s greatest spectacle would not be denied a crowd while delivering more guaranteed games for Victorian supporters. Confirmation of the Grand Final date also means that the Government can lock in the popular AFL Grand Final eve public holiday for Friday, 23 October – a “Thank You Day” for Victorians who have made so many sacrifices as part of the community effort to contain the spread of coronavirus. The MCG first hosted the Grand Final in 1902 and under the terms of the new agreement between the Government and the AFL confirmed last night, the match will be played at the ground until at least 2058 – a one-year extension on the existing contract. In addition, the MCG has been guaranteed an extra two contracted games in each of the 2022 and 2023 seasons, taking the minimum number of AFL games at the ground in each year to 45. -

The Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) Was Established in 1853 When Lieutenant- Governor La Trobe Provided 10 Acres of Land in Yarra Park to the Melbourne Cricket Club

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Melbourne Cricket Ground Other Names: MCG, The G Place ID: 105885 File No: 2/11/033/0159 Primary Nominator: Nomination Date: Principal Group: Recreation and Entertainment Status Legal Status: 02/11/2005 - Indicative place Admin Status: 15/11/2005 - Under assessment by AHC--Australian place Assessment Assessor: Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: Heritage Victoria : Entered in State Heritage List Location Nearest Town: Jolimont Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 7 Address: Brunton Av, Jolimont, VIC 3002 LGA: Melbourne City (Current) VIC Location/Boundaries: About 7ha, Brunton Avenue, Jolimont, being that area entered in the Victorian Heritage Register on 12 April 2001 and identified as: 1. All land marked L1 on Diagram 1928 held by the Executive Director being all of the land contained in Crown Grant Volume 5925, Folio 828. 2. All the buildings and features marked as follows on Diagram 1928 held by the Executive Director: B1 Members Pavilion, B2 Northern (Olympic) Stand, B3 Western (WH Ponsford) Stand, B4 Great Southern Stand, B5 Light Towers (6). Assessor's Summary of Significance: The Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) was established in 1853 when Lieutenant- Governor La Trobe provided 10 acres of land in Yarra Park to the Melbourne Cricket Club. In the intervening 150 years the MCG has developed into one of the largest, most recognisable and modern sports stadiums in the world. The MCG is the home of the Melbourne Cricket Club, the first cricket club in Victoria and a major contributor to the development of cricket in Victoria and Australia from the middle of the nineteenth century.