2007 Cesar Chavez Day of Service and Learning Citrus Freeze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements

MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ, AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by ANDREA SHAN JOHNSON Dr. Robert Weems, Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2006 © Copyright by Andrea Shan Johnson 2006 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS Presented by Andrea Shan Johnson A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________________ Professor Robert Weems, Jr. __________________________________________________________ Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________________ Professor Jeffery Pasley __________________________________________________________ Professor Abdullahi Ibrahim ___________________________________________________________ Professor Peggy Placier ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to many people for helping me in the completion of this dissertation. Thanks go first to my advisor, Dr. Robert Weems, Jr. of the History Department of the University of Missouri- Columbia, for his advice and guidance. I also owe thanks to the rest of my committee, Dr. Catherine Rymph, Dr. Jeff Pasley, Dr. Abdullahi Ibrahim, and Dr. Peggy Placier. Similarly, I am grateful for my Master’s thesis committee at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, Dr. Annie Gilbert Coleman, Dr. Nancy Robertson, and Dr. Michael Snodgrass, who suggested that I might undertake this project. I would also like to thank the staff at several institutions where I completed research. -

Leroy Chatfield 1963-1973

LeRoy Chatfield 1963–1973 The NFWA, etc. Documentation Project “Cesar Chavez and His Farmworker Movement” Dedication: To each volunteer in the farmworker movement who worked with such energy, dedication, and self-sacrifice to build the first farm labor union in the history of the United States. If I have anything to say about it, your good work will not go undocumented. Chapter One Interview with Professor Paul Henggeler In Memoriam: Paul R Henggeler Professor of History, University of Texas–Pan American December 12, 2004 I never met Professor Henggeler in person nor talked with him on the telephone. Our only communication was by way of letter and email. He first wrote in November of 2002, asking for my cooperation by answering some of his questions about Cesar Chavez. I agreed to do so, but only in writing. For the next six months he asked pages of questions, and I answered them. It was this exchange with Professor Henggeler that laid the groundwork for the creation of the farmworker documentation project, which began in May of 2003. Now, 20 months later, 188 essays have been written, several thousand emails have been exchanged, and almost 1000 former farmworker movement volunteers have been identified and contacted. All of this can be traced back to the research of one young academic historian. But now he is gone. Not yet 50 years old, he died of an apparent heart attack on July 22, 2004. What a great loss. I know nothing about him personally, except that he was married. I know from our correspondence that he spent the past six years of his life researching and writing about “Cesar Chavez’s leadership of the farmworker movement.” In one of my last communications with Paul, he wrote, “Hi, LeRoy: I can’t thank you enough for the CD-ROM (the essays) and your decision to get folks ‘talking’ about their experiences in the UFW before it all evaporates.” For my part, I cannot thank Paul enough for his support, and affirmation of the documentation project. -

Cesar Chavez Newsletter

M A R C H 3 1 , 2 0 2 1 IN CELEBRATION OF CESAR CHAVEZ DAY I m a g i n e w a k i n g u p e v e r y d a y , h e a d i n g t o a j o b , w h e t h e r i t b e t h e b l a z i n g h o t s u n o r p o u r i n g r a i n , y o u w o r k e d i n d i r e c t c o n t a c t w i t h t h e e l e m e n t s . I m a g i n e f a c i n g t h e s e h a r s h c o n d i t i o n s e a c h d a y , k n o w i n g y o u w o u l d r e c e i v e u n f a i r w a g e s . T h i s i s w h a t f a r m w o r k e r s e n d u r e d . M e x i c a n - A m e r i c a n l a b o r l e a d e r a n d c i v i l r i g h t s a c t i v i s t C e s a r C h a v e z r o s e t o t h e o c c a s i o n t o b r i n g a w a r e n e s s a n d m a k e c h a n g e f o r f a r m w o r k e r s t h r o u g h o u t t h e U . -

Teacher Resources Guide

KinderCaminata Teacher Resources Guide Sample Career & College Readiness Aligned California State Content Standards Week-Long Sample Schedule Sample Classroom Lesson Plans & Activities KinderCaminata Event Information 1 DEDICATION We would like to express our sincere gratitude for the dedication of community and education leaders from Fullerton, Anaheim City and La Habra school districts, Fullerton College, Orange County Office of Education, and Los Amigos of Orange County who devoted their time to plan and coordinate an educational program that inspires thousands of young children to build dreams of a college education and expand their knowledge of the many different career opportunities available to them in the future. This resource guide is dedicated to our children – Our future! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2016 KinderCaminata Advisory Board K-12 School Partners Nancy Marcus, Educational Services Fullerton School District Yesenia Navarro, Parent Engagement Anaheim City School District Pam Cunningham, School Principal La Habra School District Orange County Office of Education Omar Guillen, English Language Development & Multi-Literacy Pathways Community Partner Adela Lopez, Los Amigos of Orange County & Fullerton College Faculty Emeritus Fullerton College Staff and Faculty Dr. Kathy Bakhit, Dean of Social Sciences Jane Ishibashi, Librarian Elsa Aguirre, Transfer Center Counselor Amber Gonzalez, Ethnic Studies Faculty Sharon Deleon, Early Childhood Education Faculty Jim McKamy, Director Campus Safety Pete Snyder, Physical Education Faculty Lisa -

Cesar Chavez Film Debuts March 28 “History Is Made One Step at a Time”

F MARCH 2014 “A VISION FOR THE FUTURE ” Cesar Chavez Film Debuts March 28 “History Is Made One Step At A Time” The most anticipated film about the most important Latino leader in the United States is coming to theaters on March 28, 2014. Phoenix is one of the lucky states to have a premiere of the film on Thursday, March 13, 2014 at the Orpheum Theater. The upcoming film directed by Diego Luna, goes in depth about the struggles farm workers faced and how Cesar Chavez community organizing was effective in fighting for fair wages, good working conditions, dignity and respect for the men and women in the fields. The film highlights important events in the history of the farmworkers movement and the sacrifices Cesar Chavez and others made for the cause through non-violence acts. This is a first class film with Michael Peña as Cesar Chavez, America Ferrera as Helen Chavez, Rosario Dawson as Dolores Huerta who with Cesar is co-founder of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) and John Malkovich co-stars as the owner of an industrial grape farm. The Si Se Puede attitude Cesar maintained during the hard times of the organizing efforts has transcended generations. I encourage you to watch this powerful film that will take you back to social history and where the fights against discrimination all began with Cesar Chavez. For more information about the film, please visit www.cesarechavezfoundation.org. “I am an organizer, not a union leader. A good organizer has to work hard and long. There are no shortcuts. -

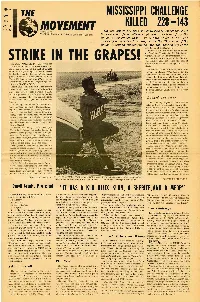

Strike in the Grapes!

MISSISSIPPI CHALLENGE OCT 1965 VOL 1 KILLED 228 -143 NO. 10 MOVEMENT Published by On September 17, 1965 the challenge to unseat the white The Student Nonviolent Coord inating ,Committee of Ca Iifornia Congressmen from Mississippi was dismissed from the House' of Representatives, by a vote of 228 to 143. The motion for dismissal, coming from the Chairman of the House Elections Subcommittee, did not mention any of the real issues of the Challenge. Instead the motion called for dismissal on "technical" grounds. The Mississippi Coqgressmen had valid certificates ofelec tion on file in the office of the Clerk of STRIKE IN THE GRAPES! 'the House; they had taken the oath of DELANO, CALIFORNIA - The cry in the office administered by the Speaker of the San Joaquin Valley north of Bakersfield, in House. the grape fiels now at the peak of harvest Moreover, as the official report for dis time, is Huelgal Huelgal It means Strikel missal complained, "The fact is that the in Spanish and is the cry of the roving contestants did not avail themselves of the picket lines of the independent National proper legal steps to challenge their al Farm Workers Association (FWA) and the leged exclusions from the registration books Agricultural Workers Organizing Com and ballots prior to election, nor did they mittee, AFL-CIO (AWOC). even attempt to challenge the issuance of According to one source it is the largest the Governor's certificate of election, in strike of agricultural workers in the Valley Federal District Court, after the election since the Modesto cotton strike of 1938. -

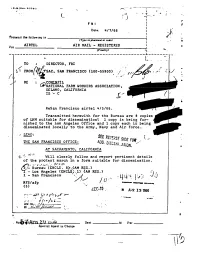

Cesar Chavez Part 2 of 17

ID ll How 5-22-C-I; »-. _ ,-92 -' I @- _ I Q nv 1'. _ 1* ' F B I D010: I-I/' 1/BE Transmit the following: in _ W J Type in ploinnsl or coda! _ AIRTEL AIR HAIL - REGISTERED Via. __ ___ __ H t __ _ __ __ _ § Priority! @---qu-»--$1--1--1;;-q.---|-t_1.--51-111--_--11--sq-1-@1 n- Q.C 54 92 'ro = nnu-:c'ron, FBI _ / _' .' - _ 3| rnonp sac, sax mmcxsco 00-55900! 1/ ." H, ,,,/ 2 / /1» .1 ll? at = cguiunz. ; @uA'r10uA1. man wonxzns ASSOCIATION , nsuwo, cnnzronum IS 1 C gr ReSan Francisco airtel H/S/66. Transmitted herewith for the Bureau are 8 copies ; of LHH suitable for dissemination! 1 copy is being fur- M nished to the Los Angeles Uffice and 1 copy each is being disseminated locally to the Army, Navy and Air Force -" F519 st: REVER 5- .=SIDE Fog , L "' THE ism FR{NCISCO_0FFIC§i ADD. D1-'S°£m..-AnQ;q_ 92 Ag SACR.f92§!fI£INT0,7 cA:..Irogn;§ Q v-"J" .-will92r'"92< closely follow and report pertinent details of the protest march in a form suitable for dissemination. d --H Bureau v-Jul-iv ENCLS.fr/--D 8_!:_-, REG.! AH - Los Angeles ENCI-S;--_.1! AH REG.! 1 - San Francisco L 1 l J . RPS/afp -._'_; - "-"""lII'I_|u---q ca 5 ~ iir-C-T9. , -i c -s A3-#2131956 I 1"?" Z-f¢;{i'u,_ ,- 6'"!-'I -HI-In - V -___-_" 1:-5': rY/"'/9.§.___ 1' mwrm- gy ___¢.:,',-"l5;',: I/'£1 " 92 . -

Food in American Culture and Literature

Food in American Culture and Literature Food in American Culture and Literature: Places at the Table Edited by Carl Boon, Nuray Önder and Evrim Ersöz Koç Food in American Culture and Literature: Places at the Table Edited by Carl Boon, Nuray Önder and Evrim Ersöz Koç This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Carl Boon, Nuray Önder, Evrim Ersöz Koç and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4739-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4739-1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Nuray Önder and Carl Boon Safety for Our Souls: Food Activism and the Environmental and Women’s Movements, 1960s–1980s ................................................... 7 Annessa Ann Babic and Tanfer Emin Tunc From a Commodity to an Instrument of Social Interaction: The Sociology of Coffee in the United States .......................................... 26 Gaye Gökalp Yılmaz The Addictive Foods of Neoliberal Capitalism: From the -

César E. Chávez Was an Activist Who Fought for Equal Rights for Farm Workers Across the United States Beginning in the 1960S Until His Death in 1993

2nd Annual César E. Chávez Contest “Honoring our Land, People, and All Living Creatures” César E. Chávez was an activist who fought for equal rights for farm workers across the United States beginning in the 1960s until his death in 1993. He, with Dolores Huerta, founded the United Farm Workers (UFW) Union where he fought for civil rights for Latinos and farmworkers. He believed in nonviolent demonstrations and civil disobedience, including protests, marches, and fasts, with his longest fast being 36 days. César E. Chávez inspired others to fight using nonviolent methods and to stand up for their rights. The infamous phrase “Si Se Puede” (It Can Be Done) was coined during this movement and is still used to unite the Latino community in their fight for la causa (the cause). We are pleased to introduce the 2nd annual celebration of the birth of César E. Chávez. This event focuses on educating our communities about the legacy of César E. Chávez, an unselfish advocate of social justice and respect for human dignity. The César E. Chávez Birthday Celebration is organized by a steering committee of community members, school representatives, corporate leaders, and Marcus Center staff. We are proud to begin the tradition of celebrating the life and work of César E. Chávez. The theme of the writing contest is “Honoring our Land, People, and All Living Creatures” Students may relate this theme to themselves or others in their family, school, neighborhood, or the world. How do you or your family show love and respect for the environment? How do you show respect to your family, teachers and friends? Eligibility/Categories The writing contest is open to students in grades K-12 who live in the city of Milwaukee, or are enrolled in a school, either public or private, within the city of Milwaukee. -

The New César E. Chávez National Monument!

César E. Chávez National Park Service National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior Welcome to the New César E. Chávez National Monument! President Barack Obama signed a Presidential Proclamation on October 8, 2012, creating the César E. Chávez National Monument. This peaceful “La Paz” site, in the Tehachapi Mountains northeast of Los Angeles, commemorates Cesar Chavez and the struggles and accomplishments of the farm worker movement. A visitor center and the memorial garden where Cesar Chavez is buried are open to the public. This new national monument was established through a process separate from the Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study, but was informed by the draft fi ndings of the study. The National Chavez Center offered to donate a portion of the property to the National Park Service. This donation created an opportunity for the President to use the Antiquities Act to take immediate action to protect and interpret this area as a national monument. President Barack Obama addresses the crowd. NPS photo. “Today, La Paz joins a long line of national monuments -- stretching from the Statue of Liberty to the Grand Canyon -- monuments that tell the story of who we are as Americans. It’s a story of natural wonders and modern marvels; of fi erce battles and quiet progress. But it’s also a story of people -- of determined, fearless, hopeful people who have always been willing to devote their lives to making this country a little more just and a little more free.” – from President Obama’s dedication of the monument Under a glorious blue sky on a crisp fall day, thousands of people gathered at La Paz, the headquarters of the United Farm Workers, DID YOU KNOW? to celebrate and witness the creation of the César E. -

Austin Fire Department Subject Guide

Austin Fire Department Subject Guide Sources of Information Relating to Austin Fire Department Austin History Center Austin Public Library Compiled by Rusty Heckaman, Bob Rescola, and Toni Cirilli, 2019 The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable research materials that document the Austin Fire Department. The materials in this resource guide are arranged by format, including textual and photographic items as well as audio and video. Austin Fire Department Subject Guide 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF AUSTIN FIRE DEPARTMENT .................................................................... 3 ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES COLLECTION .................................................................................... 4 ARCHIVES AND MANUSCRIPTS COLLECTION ............................................................................... 6 OVERSIZE ARCHIVES ................................................................................................................................. 8 AUSTIN FILES – SUBJECT: TEXT AND PHOTOGRAPHS ............................................................ 10 AUSTIN FILES – BIOGRAPHY: TEXT AND -

Historic Austin Location Since Its 1892 Renovation by Prominent Local Banker, Ira Evans

ONLINE AUSTIN HISTORY RESOURCES Austin History Center austinhistorycenter.org Austin Historical Survey Wiki austinhistoricalsurvey.org Austin Museum Partnership austinmuseums.org City of Austin austintexas.gov Preservation Austin preservationaustin.org Texas Historical Commission thc.state.tx.us Texas State Historical Association tshaonline.org/handbook Our Visitor Center welcomes you to Austin with maps, city information and walking tours. AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St. 512-478-0098 | austintexas.org Historic Sixth Street and The Driskill Hotel. DISCOVER AUSTIN’S RICH HISTORY. With 180 sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including 17 historic districts and 2 National Historic Landmarks, Austin puts you at the heart of Texas history. From the Texas State Capitol to the Paramount Theatre, The Driskill Hotel to Barton Springs, the heritage of the Lone Star State lives and breathes throughout our city. We invite you to explore, experience and enjoy Austin’s many memorable attractions and make our history part of yours. THE TEXAS STATE 1 CAPITOL COMPLEX TEXAS STATE CAPITOL BUILDING Detroit architect Elijah E. Myers’ 1888 Renaissance Revival design echoes that of the U.S. Capitol, but at 302 feet, the Texas State Capitol is 14 feet higher. The base is made of rusticated Sunset Red Texas granite; the dome is made of cast iron and sheet metal, topped by a Goddess of Liberty statue. The seals on the south façade commemorate the six governments that have ruled in Texas over time: Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the Confederate States of America and the United States. Myers also designed the state capitols of Michigan and Colorado.