573KB***International Commercial Mediation: the Singapore Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPENING of the LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General

OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C. 11 January 2021 May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Justices of the Court of Appeal, Judges of the Appellate Division, Judges and Judicial Commissioners, Introduction 1. The past year has been an extremely trying one for the country, and no less for my Chambers. It has been a real test of our fortitude, our commitment to defend and advance Singapore’s interests, and our ability to adapt to unforeseen difficulties brought about by the COVID-19 virus. I am very proud of the good work my Chambers has done over the past year, which I will share with you in the course of my speech. I also acknowledge that the past year has shown that we have some room to grow and improve. I will outline the measures we have undertaken as an institution to address issues which we faced and ensure that we meet the highest standards of excellence, fairness and integrity in the years to come. 2. My speech this morning is in three parts. First, I will talk about the critical legal support which we provided to the Government throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Second, I will discuss some initiatives we have embarked on to future-proof the organisation and to deal with the challenges which we faced this past year, including digitalisation and workforce changes. Finally, I will share my reflections about the role we play in the criminal justice system and what I consider to be our grave and solemn duty as prosecutors. -

Singapore Judgments

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2021] SGCA 57 Civil Appeal No 113 of 2020 Between (1) Crest Capital Asia Pte Ltd (2) Crest Catalyst Equity Pte Ltd (3) The Enterprise Fund III Ltd (4) VMF3 Ltd (5) Value Monetization III Ltd … Appellants And (1) OUE Lippo Healthcare Ltd (formerly known as International Healthway Corporation Ltd) (2) IHC Medical Re Pte Ltd … Respondents In the matter of Suit No 441 of 2016 Between (1) OUE Lippo Healthcare Ltd (formerly known as International Healthway Corporation Ltd) (2) IHC Medical Re Pte Ltd … Plaintiffs And (1) Crest Capital Asia Pte Ltd (2) Crest Catalyst Equity Pte Ltd (3) The Enterprise Fund III Ltd (4) VMF3 Ltd (5) Value Monetization III Ltd (6) Fan Kow Hin (7) Aathar Ah Kong Andrew (8) Lim Beng Choo … Defendants JUDGMENT [Civil Procedure] — [Costs] [Civil Procedure] — [Judgment and orders] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 CONSEQUENTIAL ORDER ISSUE.............................................................3 BACKGROUND.................................................................................................3 THE PARTIES’ POSITIONS .................................................................................4 VMF3 and VMIII........................................................................................4 The respondents .........................................................................................5 OUR DECISION.................................................................................................7 -

OPENING of the LEGAL YEAR 2019 Speech by Attorney-General

OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2019 Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C. Monday, 7 January 2019 Supreme Court Building, Level Basement 2, Auditorium May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Judges of Appeal, Judges and Judicial Commissioners of the Supreme Court, Introduction: AGC in Support of the Government, for the People 1 2018 was a fast-paced year for the Government and for the Attorney-General’s Chambers. The issues occupying the thoughts of Singapore’s leaders were complex and varied, with several key themes coming to the fore. These themes shaped our work over the past year, as we strove to be a strategic partner in support of the Government’s plans and initiatives, for the benefit of our country and its citizens. I will touch on three of these themes. 2 The first theme was our Smart Nation. This initiative aims to tap on the ongoing digital revolution in order to transform Singapore through technology. The Smart Nation vision is for Singapore to be a world-class leader in the field of digital innovation, resting on the triple pillars of a digital economy, digital government, and digital society. The Smart Nation revolution will play a critical part in ensuring our continued competitiveness on the world stage, powered by digital innovation. 1 3 Data sharing was and continues to be a critical aspect of this initiative. To this end, a new law was passed in 2018 which introduced a data sharing regime among different agencies in the Singapore Government. The Public Sector (Governance) Act 2018, which was drafted by our Chambers in support of this initiative, underpins and formalises a data sharing framework for the Singapore public sector. -

Eighteenth Annual International Maritime Law

EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL MARITIME LAW ARBITRATION MOOT 2017 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY TEAM 10 ON BEHALF OF: AGAINST: INFERNO RESOURCES SDN BHD FURNACE TRADING PTE LTD AND IDONCARE BERJAYA UTAMA PTY LTD CLAIMANT RESPONDENTS COUNSEL Margery Harry Declan Haiqiu Ai Godber Noble Zhu TEAM 10 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... III LIST OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................................ V STATEMENT OF FACTS ................................................................................................................ 1 APPLICABLE LAW ......................................................................................................................... 2 I. SINGAPOREAN LAW APPLIES TO ALL ASPECTS OF THE DISPUTE ............................................... 2 A. Singaporean law governs the procedure of the arbitration ................................................... 2 B. Singaporean law is the substantive law applying to FURNACE and INFERNO’s dispute ....... 2 C. Singaporean law is also the substantive law applying to FURNACE and IDONCARE’s dispute ................................................................................................................................... 3 ARGUMENTS ON THE INTERIM APPLICATION FOR SALE OF CARGO ......................... 4 II. A VALID AND ENFORCEABLE LIEN -

Political Defamation and the Normalization of a Statist Rule of Law

Washington International Law Journal Volume 20 Number 2 3-1-2011 The Singapore Chill: Political Defamation and the Normalization of a Statist Rule of Law Cameron Sim Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Cameron Sim, The Singapore Chill: Political Defamation and the Normalization of a Statist Rule of Law, 20 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 319 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol20/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compilation © 2011 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association THE SINGAPORE CHILL: POLITICAL DEFAMATION AND THE NORMALIZATION OF A STATIST RULE OF LAW Cameron Sim† Abstract: Recent cases involving opposition politicians and foreign publications, in which allegations of corruption leveled against both the executive and the judiciary were found to be defamatory and in contempt of court, struck at the heart of Singapore’s ideological platform as a corruption-free meritocracy with an independent judiciary. This article examines the implications of these cases for the relationship between the courts, the government, and the rule of law in Singapore. It is argued that judicial normalization of the government’s politics of communitarian legalism has created a statist and procedural rule of law that encourages defamation laws to chill political opposition. -

Part a Bar Course 2014 Company Law

PART A BAR COURSE 2014 COMPANY LAW Associate Professor Dan W. Puchniak Assistant Professor Umakanth Varottil Assistant Professor Wee Meng Seng LECTURE 1 INTRODUCTION AND SEPARATE PERSONALITY DOCTRINE Assistant Professor Wee Meng Seng PART A BAR COURSE 2014 COMPANY LAW Introduction and Separate Personality Doctrine Tan Cheng Han (ed) Walter Woon on Company Law (Rev 3rd edn, 2009) Chapters 1 & 2 Some of the cases cited below can be found in Sealy & Worthington (ed) Sealy and Worthington’s Cases and Materials in Company Law (10th edn, 2013) (S&W), and David Kershaw Company Law in Context: Text and Materials (2nd edn, 2012) 1. Introduction To a lay person the company is a form of business organisation, much like a sole proprietorship or partnership. This is of course true of most companies. But unlike a sole proprietorship or partnership, a company can be used for purposes other than a business vehicle, for eg, in education, charity or other fields of human activity. A company is a versatile form of organisation, but for the purposes of this course, we shall focus on the company as a business vehicle. Company law is one of the most dynamic branches of law. It has seen substantial reforms in various jurisdictions in recent years. For example, UK undertook a mammoth review of its Companies Act which culminated in the enactment of its Companies Act of 2006. Closer home, the Company Legislation and Regulatory Framework Committee (‘CLRFC’) was appointed by the Government in 1999 and submitted its report recommending substantial reforms in 2002. Most of its recommendations have since become law. -

Chan Sek Keong the Accidental Lawyer

December 2012 ISSN: 0219-6441 Chan Sek Keong The Accidental Lawyer Against All Odds Interview with Nicholas Aw Be The Change Sustainable Development from Scraps THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE FACULTY OF LAW Contents DEAN’S MESSAGE A law school, more so than most professional schools at a university, is people. We have no laboratories; our research does not depend on expensive equipment. In our classes we use our share of information technology, but the primary means of instruction is the interaction between individuals. This includes teacher and student interaction, of course, but as we expand our project- based and clinical education programmes, it also includes student-student and student-client interactions. 03 Message From The Dean MESSAGE FROM The reputation of a law school depends, almost entirely, on the reputation of its people — its faculty LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS THE DEAN and staff, its students, and its alumni — and their 05 Benefactors impact on the world. 06 Class Action As a result of the efforts of all these people, NUS 07 NUS Law in the World’s Top Ten Schools Law has risen through the ranks of our peer law 08 NUS Law Establishes Centre for Asian Legal Studies schools to consolidate our reputation as Asia’s leading law school, ranked by London’s QS Rankings as the 10 th p12 09 Asian Law Institute Conference 10 NUS Law Alumni Mentor Programme best in the world. 11 Scholarships in Honour of Singapore’s First CJ Let me share with you just a few examples of some of the achievements this year by our faculty, our a LAWMNUS FEATURES students, and our alumni. -

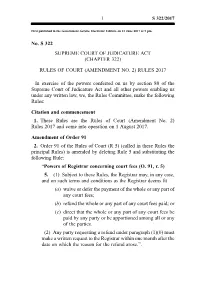

Rules of Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 2017

1 S 322/2017 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 21 June 2017 at 5 pm. No. S 322 SUPREME COURT OF JUDICATURE ACT (CHAPTER 322) RULES OF COURT (AMENDMENT NO. 2) RULES 2017 In exercise of the powers conferred on us by section 80 of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act and all other powers enabling us under any written law, we, the Rules Committee, make the following Rules: Citation and commencement 1. These Rules are the Rules of Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 2017 and come into operation on 1 August 2017. Amendment of Order 91 2. Order 91 of the Rules of Court (R 5) (called in these Rules the principal Rules) is amended by deleting Rule 5 and substituting the following Rule: “Powers of Registrar concerning court fees (O. 91, r. 5) 5.—(1) Subject to these Rules, the Registrar may, in any case, and on such terms and conditions as the Registrar deems fit — (a) waive or defer the payment of the whole or any part of any court fees; (b) refund the whole or any part of any court fees paid; or (c) direct that the whole or any part of any court fees be paid by any party or be apportioned among all or any of the parties. (2) Any party requesting a refund under paragraph (1)(b) must make a written request to the Registrar within one month after the date on which the reason for the refund arose.”. S 322/2017 2 Amendment of Appendix B 3. Appendix B of the principal Rules is amended — (a) by deleting paragraph (2) of item 63; and (b) by inserting, immediately after item 64, the following sub‑heading and item: Document to be No. -

Lord Phillips in Singapore SAL Annual Lecture 2006

MICA (P) No. 076/05/2006 September — October 2006 interSINGAPOREinterSINGAPORE ACADEMYACADEMY seseOFOF LAWLAW SALSAL AnnualAnnual LectureLecture 2006:2006: LordLord PhillipsPhillips inin SingaporeSingapore ChiefChief JusticeJustice ChanChan VisitsVisits thethe MalaysianMalaysian CourtsCourts InIn Summary:Summary: SAL’sSAL’s StrategicStrategic PlanningPlanning RetreatRetreat BDFQMQDPNIBTUIFTPMVUJPOUPZPVSBSDIJWJOHOFFET8JUI PVSTVQFSJPSTDBOUPGJMFTFSWJDFT ZPVOFWFSIBWFUPXPSSZ BCPVUVOXBOUFEQBQFSCVMLBHBJO 4FSWJDFTJODMVEF "UP"TJ[FQBQFSTDBO )JHI3FTPMVUJPOTDBOOJOH 4BWFUP1%'GPSNBU EJHJUBMmMFBSDIJWJOHIBTOFWFSCFFONBEFFBTJFS Powered by g Image Logic® GPSNPSFJOGPSNBUJPO WJTJUXXXBDFQMQDPNTH www.oce.com.sg [email protected] BDFQMQDPN1UF-UE FQSJOUJOHTDBOOJOHIVC 5FMFORVJSZ!BDFQMQDPNTH INTER ALIA The tragic events of 9/11 starkly remind us that the world now lives in a much more uncertain time. With this in mind, the legal profession in Singapore gathered this year, on 29 August 2006, for the 13th Singapore Academy of Law Annual Lecture delivered by The Right Honourable The Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. The lecture titled “Terrorism and Human Rights” highlighted the struggles facing the United Kingdom in balancing the right of a sovereign state to protect those within its territory from acts of terror, with the right of every individual to free access to and due process of the law – regardless of which side of the law an individual happens to fall. Lord Phillips illustrated, through detailed references to UK legislation and case law, how the UK courts have mediated between the Government’s responses to threats to national security and the need for such responses to be sensitive to the regime of human rights law applicable in the UK. In this issue of Inter Se, we feature highlights from Lord Phillips’s timely and thoughtful lecture together with excerpts from an interview with Lord Phillips on other changes taking place in the UK legal sphere. -

Poondy Radhakrishnan and Another V Sivapiragasam S/O Veerasingam

Poondy Radhakrishnan and Another v Sivapiragasam s/o Veerasingam and Another [2009] SGHC 228 Case Number : OS 904/2008 Decision Date : 09 October 2009 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Belinda Ang Saw Ean J Counsel Name(s) : Manimaran Arumugam (Mani & Partners) for the plaintiffs; B Ganeshamoorthy (Colin Ng & Partners LLP) for the defendants Parties : Poondy Radhakrishnan; Visvalingam Naidu s/o Munisamy — Sivapiragasam s/o Veerasingam; Megatech System & Management Pte Ltd Companies 9 October 2009 Belinda Ang Saw Ean J: 1 This is an application under s 216A of the Companies Act (Cap 50, 2006 Rev Ed) (“the Act”) for leave to bring a derivative action in the name and on behalf of the second defendant, Megatech System & Management Pte Ltd (“Megatech System”) against the first defendant, Sivapiragasam s/o Veerasingam (“Sivapiragasam”) for the breach of fiduciary duties as a director of Megatech System. I allowed the application on 26 March 2009 and the defendants have since appealed against my decision. I now set out my reasons for doing so. Background 2 Megatech System was incorporated on 11 June 1994 with Sivapiragasam and one Ganapathy s/o P S Sundram holding one share each. At all material times, Sivapiragasam was the managing director of Megatech System. Later on, Sivapiragasam invited the plaintiffs to join Megatech System as part of an effort to secure funding for the company. Funding was required because the company was operating at a loss. At that time, Megatech System was involved in the business of providing security guard services and scaffolding for ship repairs. The plaintiffs did become shareholders and were subsequently appointed directors on 9 February 1999. -

Singapore's Fifth CEDAW Periodic Report

SINGAPORE’S FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT TO THE UN COMMITTEE FOR THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN October 2015 SINGAPORE’S FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT TO THE UN COMMITTEE FOR THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN Published in October 2015 MINISTRY OF SOCIAL AND FAMILY DEVELOPMENT REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior consent from the Ministry of Social and Family Development. ISBN 978-981-09-7872-3 FOREWORD 03 FOREWORD This year marks the 20th anniversary of Singapore’s accession to CEDAW. It is also the year Singapore celebrates the 50th year of our independence. In this significant year, Singapore is pleased to present its Fifth Periodic Report on the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). This Report covers the initiatives Singapore introduced from 2009 to 2015, to facilitate the progress of women. It also includes Singapore’s responses to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s (Committee) Concluding Comments (CEDAW/C/SGP/CO/4/Rev.1) at the 49th CEDAW session and recommendations by the Committee’s Rapporteur on follow-up in September 2014 (AA/follow-up/Singapore/58). New legislation and policies were introduced to improve the protection of and support for women in Singapore. These include the Protection from Harassment Act to enhance the protection of persons against harassment, and the Prevention of Human Trafficking Act to criminalise exploitation in the form of sex, labour and organ trafficking. -

Small Law Firms 92 Social and Welfare 94 Solicitors’ Accounts Rules 97 Sports 98 Young Lawyers 102 ENHANCING PROFESSIONAL 03 STANDARDS 04 SERVING the COMMUNITY

OUR MISSION To serve our members and the community by sustaining a competent and independent Bar which upholds the rule of law and ensures access to justice. 01 OUR PEOPLE 02 GROWING OUR PRACTICE The Council 3 Advocacy 51 The Executive Committee 4 Alternative Dispute Resolution 53 Council Report 5 Civil Practice 56 The Secretariat 7 Continuing Professional Development 59 President’s Message 8 Conveyancing Practice 61 CEO’s Report 15 Corporate Practice 63 Treasurer’s Report 27 Criminal Practice 65 Audit Committee Report 31 Cybersecurity and Data Protection 68 Year in Review 32 Family Law Practice 70 Statistics 48 Information Technology 73 Insolvency Practice 74 Intellectual Property Practice 76 International Relations 78 Muslim Law Practice 81 Personal Injury and Property Damage 83 Probate Practice and Succession Planning 85 Publications 87 Public and International Law 90 Small Law Firms 92 Social and Welfare 94 Solicitors’ Accounts Rules 97 Sports 98 Young Lawyers 102 ENHANCING PROFESSIONAL 03 STANDARDS 04 SERVING THE COMMUNITY Admissions 107 Compensation Fund 123 Anti-Money Laundering 109 Professional Indemnity 125 Inquiries into Inadequate Professional Services 111 Report of the Inquiry Panel 113 05 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 06 PRO BONO SERVICES 128 132 07 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 227 This page is intentionally left blank. OUR PEOPLE The council (Seated L to R): Lim Seng Siew, M Rajaram (Vice-President), Gregory Vijayendran (President), Tito Shane Isaac, Adrian Chan Pengee (Standing L to R): Sui Yi Siong (Xu Yixiong), Ng Huan Yong, Simran Kaur Toor,