From Innovation to Provocation, China's Artists on a Global Path

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012

Bao Dong Rethinking Practices within the Art System: The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012 The Origin of the Term “Self-Organization” in China The term “self-organization” was first used in the context of contemporary Chinese art in 2005 at the Second Guangzhou Triennial curated by Hou Hanru, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Guo Xiaoyan. Self-organization was one of the special projects of the triennial, and there were two panel discussions on the topic. The exhibition theme “Beyond” focused on the topic of alternative modernity in China and non-Western countries, and the term self-organization was defined by the following statements: “A number of independent art organizations, institutions, and communities have taken an active role in artistic creation and practice” and “their projects are often diverse, flexible” and “self-induced in nature.”1 Altogether, twenty-four self- organized groups2 were included in this project, and for the curators, the concept of “self-organization” was used to differentiate independent and autonomous organizations from those attached to government systems or political parties. This feature is also the fundamental difference between the various artist-run autonomous organizations and the organizations within the conventional art system as constituted by Chinese Artists Association, along with the various academies of painting, art institutes, museums, and so on. In other words, self-organization is considered a force operating outside of the conventional art system, just as the inception, growth, and flourishing of contemporary Chinese art is believed to have been achieved outside of official systems. In terms of any independence from the conventional art system, self- organization is not a new phenomenon in the contemporary Chinese art scene. -

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art: In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao." China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu and Luke Vulpiani. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 73–86. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501300103.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 10:59 UTC. Copyright © Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, Luke Vulpiani and Contributors 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art Dong Bingfeng In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao Dong Bingfeng is regarded as one of the most active curators and art critics working on Chinese contemporary art and visual culture in mainland China today. In the past eight years he has worked at several different contemporary art museums, including the Guangdong Art Museum, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art and Iberia Center for Contemporary Art. At these leading art institutions, he explored the nature and ontology of the ‘moving image’ in its various forms – video art, new media art, video and film installations – pushing the boundaries of the various forms and decon- structing the moving image culture. Currently, Dong is the artistic director at the Li Xianting Film Fund, where he has implemented an intensive exploration into artists’ films shown in gallery spaces, or what has been recently referred to as ‘cinema of exhibition.’ China’s iGeneration co-editor Tianqi Yu interviewed Dong Bingfeng on the emerging field of ‘cinema of exhibition,’ and in the interview Dong shares some of his views on cinema and moving image culture, particularly among China’s current iGeneration. -

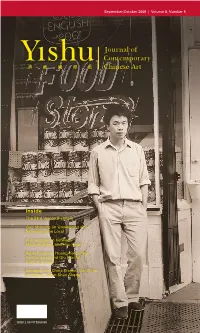

September/October 2017 Volume 16, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5 INSI DE 57th Venice Biennale Conversations with Tang Nannan, Liang Yue, Wong Ping Artist Features: Yin Xiuzhen, Fang Tong The April Photography Society US$12.00 NT$350.00 P RINTED IN TA I WAN 6 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 C ONT ENT S 28 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 On Continuum and Radical Disruption: The Venice Gathering Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker 14 Continuum—Generation by Generation: The Continuation of Artistic Creation at the 57th Venice Biennale: A Conversation with Tang 47 Nannan Ornella De Nigris 28 What Is the Sound of Failed Aspriations? Samson Young's Songs For Disaster Relief Yeewan Koon 37 Miss Underwater: A Conversation with Liang Yue Alexandra Grimmer 47 Sex in the City: Wong Ping in Conversation Stephanie Bailey 71 65 Yin Xiuzhen’s Fluid Sites of Participation: A Communal Space of Communication and Antagonism Vivian Kuang Sheng 78 The Constructed Reality of Immigrants: Fang Tong’s Contrived Photography Dong Yue Su 86 The April Photography Society: A Re-evaluation of Origins, Artworks, and Aims 87 Adam Monohon 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Wong Ping, The Other Side (detail), 2015, 2-channel video, 8 mins., 2 secs. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue 94 Gallery, Hong Kong. We thank JNBY and Lin Li, Cc Foundation and David Chau, Yin Qing, Chen Ping, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

JUNE 2005 SUMMER ISSUE Dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist

JUNE 2005 SUMMER ISSUE INSIDE Dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Huo Hanru on the 2nd Guangzhou Triennial On Curating Cruel/Loving Bodies The Yellow Box: Thoughts on Art before the Age of Exhibitions Interviews with Michael Lin and Hu Jieming From Iconic to Symbolic: Ah Xian’s Semiotic Interface Between China and the West Place and Displace: Three Generations of Taiwanese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Editor’s Note Contributors : Opening remarks Richard Vinograd p. 7 Re-Placing Contemporary Chinese Art Richard Vinograd Remarks Michael Sullivan : Prodigal Sons: Chinese Artists Return to the Homeland Melissa Chiu Between Truth and Fiction: Notes on Fakes, Copies and Authenticity in Contemporary Chinese Art Pauline J. Yao Ink Painting in the Contemporary Chinese Art World Shen Kuiyi Remarks p. 12 Richard Vinograd : Reflections on the First Chinese Art Seminar/Workshop, San Diego 1991 Zheng Shengtian Between the Worlds: Chinese Art at Biennials Since 1993 John Clark Between Scylla and Charybdis: The New Context of Chinese Contemporary Art and Its Creation since 2000 Pi Li Remarks: “Whose Stage Is It, Anyway?” Reflections on the Correlation of “Beauty” and International Exhibition Practices of Chinese Contemporary Art p. 83 Francesca Dal Lago : How Western People Support/Influence Contemporary Chinese Art Zhou Tiehai The Positioning of Chinese Contemporary Artworks in the International Art Market Uli Sigg Chinese Contemporary Art: At the Margin of the American Mainstream Jane Debevoise Remarks Britta Erickson p. 93 Artist Project: Zhou Tiehai WILL On the Edge Visiting Artists Program Britta Erickson On the Spot: The Stanford Visiting Artists Program Pauline J. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

China's Third Generation Art and Artists - Zhang Zhaohui (China Today) 2004-12-01

China's third generation art and artists - Zhang Zhaohui (China Today) 2004-12-01 Dramatic changes have taken place in the 25 years since China’s reform and opening. Since 1978 it has transmogrified from the isolated, indigent and unenlightened country of the cold war years to a world economic powerhouse. Accelerated integration into the international community has turned Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and China's other major cities into cradles for a new urbanized culture, of which consumption is a major aspect. Today's young Chinese people enjoy a level of education their parents could not even imagine. Labeled by the media and society as the "Cartoon," "New Breed," "Ultra New Human" and even "Post Human" generation, they express themselves in a manner so uninhibited as to be in direct contrast to that of their introverted and stoic elders. The broad scope of consumables available to them is manifest in their avant garde choices of clothes, hairstyles, cosmetics and jewelry, and a superior material environment and wider mental range gives them a natural affinity with European, American and Japanese popular culture. China's societal progress and economic development are reflected in its contemporary art. Representatives of the three generations of avant-garde artists that have emerged since 1978 have all achieved world acknowledgement. First was the New Wave Art Movement of the 1980s whose most famous exponents are Huang Yongping, Xu Bing, Cai Guoqiang and Gu Wenda. All born in the 1950s, these artists experienced the surreal agony of the "cultural revolution" as young adults and left for the West in the 1980s and 1990s in search of a kinder working environment. -

Ars Electronica Shows Exhibition in Shenzhen

40 Years of Humanizing Technology – Art, Technology, Society: Ars Electronica Shows Exhibition in Shenzhen (Linz, Shenzhen / October 29, 2019) With "40 Years of Humanizing Technology - Art, Technology, Society", Ars Electronica, the Chinese Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) and the Design Society Shenzhen will open their first joint exhibition at the museum of the Design Society Shenzhen on November 2, 2019. At the center of the show is the 40-year history of Linz-based Ars Electronica and thus the (media-) artistic effort to develop a technology that is primarily committed to us and to the concerns of our society(s) rather than to the economy. CAFA in turn contributes selected works from the Chinese media art scene to this debate. "40 Years of Humanizing Technology - Art, Technology, Society" can be seen at the Design Society museum in Shenzhen until February 16, 2020. From Automation to Autonomy The starting point of the exhibition is our global digital society here and now; 4.5 billion people who use the World Wide Web today to work, shop, play, share and learn. People in whose everyday lives technology is omnipresent and self-evident. And yet; this was just the beginning. Thanks to the computing power available today and the huge amounts of data produced by our digital society, artificial neural networks are for the first time unfolding their disruptive potential. We are experiencing the hour of "machine learning" and other applications of "artificial intelligence", which are no longer programmed by us, but "teach themselves from data". Even though these systems have no intelligence like we humans do, they still herald the transition from mere automation to autonomy. -

On Huang Yong Ping

September/October 2009 | Volume 8, Number 5 Inside The 53rd Venice Biennale Gao Shiming on Unweaving and Rebuilding the Local A Conversation between Michael Zheng and Hou Hanru Artist Features: Huang Yong Ping, Hu Xiaoyuan and Qiu Xiaofei, Chen Hui-chiao Reviews: The China Project, Qiu Zhijie, Ai Weiwei, Shan Shan Sheng US$12.00 NT$350.00 Ryan Holmberg The Snake and the Duck: On Huang Yong Ping “ lay sculpture is a term now used to describe an idea Isamu Huang Yong Ping, Tower Snake, 2009, aluminum, Noguchi began experimenting with in the late 930s: to use the bamboo, steel, 660 x 1189 x 1128 cm. Courtesy of the artist modernist vocabulary of sculptural form within the context of and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, P New York. leisure, recreation, and purposeless play. Most of what he designed was for children’s playgrounds and included angular swing sets in primary colors, cubistic climbing blocks, and biomorphic landscaping. At the same time, a fair number of these projects, none of which were realized in full before the 970s, have an atavistic subtext, from references to monuments of the ancient world to almost protozoan biological structures. As if to suggest that to play like a child is to reincarnate the most archaic forms of human civilization and the most primordial forms of life on earth. The same conceit resonates strongly in Tower Snake (2009), the newest work by Huang Yong Ping. First exhibited at Gladstone Gallery in New York in the summer of 2009, Tower Snake can be seen as a kind of “play sculpture” that links interactive amusement to ultimately atavistic fantasies. -

Ink Remix Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

墨 變 中 國 大 陸 臺 灣 香 港 當 Contemporary art 代 from mainland China, 藝 Taiwan and Hong Kong 術 INK REMIX Contemporary art from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong 墨 變 : 中 國 大 陸 臺 灣 香 港 當 代 藝 術 curated by Sophie McIntyre Published in association with the exhibition INK REMIX Contemporary art from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong 墨 變 : 中 國 大 陸 臺 灣 香 港 當 代 藝 術 Canberra Museum and Gallery 3 July – 18 October, 2015 Exhibition curator: Sophie McIntyre TOUR DATES Bendigo Art Gallery: 31 October 2015 – 7 February 2016 UNSW Galleries: 26 February – 21 May 2016 Museum of Brisbane: 16 September 2016 – 19 February 2017 Text © Sophie McIntyre, Pan An-yi, Eugene Wang 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or information retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. Exhibition website: www.inkremix.com.au ISBN is 978-0-9872457-3-1 Design: Coordinate Printing: Paragon Printers Australasia Canberra Museum and Gallery Cnr London Circuit and Civic Square, Canberra City, Australia www.museumsandgalleries.act.gov.au Cover Image: Ni Youyu, Galaxy, 2012-2015, 80 (approx.) painted coins, size variable (detail). Contemporary art from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong CONTENTS Chief Minister’s Foreword 墨 Andrew Barr, MLA, ACT Chief Minister 2 變 中 Director’s Foreword 國 Shane Breynard 4 大 陸 INK REMIX: Contemporary art from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong 臺 Sophie McIntyre 8 灣 All in the Name of Tradition: Ink Medium in Contemporary Chinese Art 香 港 Eugene Wang 14 當 Ink Art in Taiwan 代 An-yi Pan 20 藝 術 Artists’ Works & Essays Sophie McIntyre 27 List of Works 76 Artists’ Biographies 78 Writers’ Biographies 86 Curator’s Acknowledgements Sophie McIntyre 87 Museum Acknowledgements 89 1 INK REMIX CHIEF MINISTER’S FOREWORD I am delighted to introduce the exhibition, INK REMIX: Contemporary art from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong to Australian audiences. -

Reactivation—The 9Th Shanghai Biennale 2012 October 1, 2012–March 31, 2013

Barbara Pollack Reactivation—The 9th Shanghai Biennale 2012 October 1, 2012–March 31, 2013 The Power Station of Art, Shanghai. Courtesy of the Shanghai Biennale. igger than ever before and definitely more chaotic, the ninth edition of the Shanghai Biennale is simultaneously a great leap Bforward for China’s cultural scene and an incoherent curatorial jumble. The Biennale inaugurated a new location, the Power Station of Art, formerly the Nanshi power plant that served as the Pavilion of the Future at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. With nine thousand square meters of exhibition space within a thirty-one-thousand-square-meter facility—requiring a much bigger budget than provided by the Shanghai government—the new museum was still being renovated just two days before the opening, making it almost impossible to install on time the massive number of works by ninety artists and artists’ collectives from twenty-seven countries. Conceptual artist Qiu Zhijie, nominated this year for the Guggenheim’s prestigious Hugo Boss award, served as chief curator, and he directed a team that included Hong Kong gallerist/curator Johnson Chang Tsong-zung, media theorist Boris Groys, and former Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art director Jens Hoffmann. In addition to the exhibition at the Power Station of Art, the curators invited thirty cities, from Detroit to Auckland, 14 Vol. 12 No. 2 to host pavilions located in empty buildings along Nanjing Road, bringing over one hundred more artists to the event. Huang Yongping, Thousand Under the theme of Reactivation, Hands Kuanyin, 1997–2012, cast iron, steel, various items, a nod to its new home in a former 800 x 800 x 1800 cm.