Curiosity May Be Harmful to Cats, but How About to Unitarians? Clay Nelson © 23 February 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AJMP Vol 6-Min.Pdf

Academic Journal of Modern Philology Polish Academy of Sciences Wroclaw– Branch Philological School of Higher Education in Wroclaw– Academic Journal of Modern Philology e-ISSN 2353-3218 ISSN 2299-7164 Vol. 6 (2017) Editor-in-chief Piotr P. Chruszczewski Honorary Editor Franciszek Grucza Volume Editors Katarzyna Buczek Aleksandra R. Knapik Wrocław 2017 ACADEMIC JOURNAL OF MODERN PHILOLOGY Editor-in-chief Piotr P. Chruszczewski Honorary Editor Franciszek Grucza Volume Editors Katarzyna Buczek, Aleksandra R. Knapik Scientific Board of the Committee for Philology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Wrocław Branch: Piotr Cap (Łódź), Camelia M. Cmeciu (Galati, Romania), Piotr P. Chruszczewski (Wrocław), Marta Degani (Verona, Italy), Robin Dunbar (Oxford, UK), Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (Poznań), Francesco Ferretti (Rome, Italy), Jacek Fisiak (Poznań), James A. Fox (Stanford, USA), Stanisław Gajda (Opole), Piotr Gąsiorowski (Poznań), Franciszek Grucza (Warszawa), Philippe Hiligsmann (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium), Rafael Jiménez Cataño (Rome, Italy), Henryk Kardela (Lublin), Ewa Kębłowska-Ławniczak (Wrocław), Tomasz P. Krzeszowski (Warszawa), Barbara Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (Łódź), Ryszard Lipczuk (Szczecin), Lorenzo Magnani (Pavia, Italy), Marek Paryż (Warszawa), Michał Post (Wrocław), Stanisław Prędota (Wrocław), John R. Rickford (Stanford, USA), Hans Sauer (Munich, Germany), Aleksander Szwedek (Poznań), Elżbieta Tabakowska (Kraków), Marco Tamburelli (Bangor, Wales), Kamila Turewicz (Łódź), Zdzisław Wąsik (Wrocław), Jerzy Wełna (Warszawa), Roland -

Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models

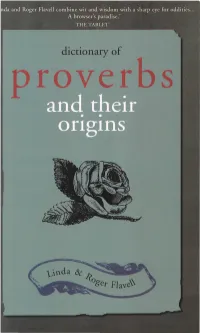

nda and Roger Flavell combine wit and wisdom with a sharp eye for oddities... A browser’s paradise.’ THE TABLET dictionary of DICTIONARY OF PROVERBS Linda Flavell completed a first degree in modern languages and has subsequent qualifications in both secondary and primary teaching. She has worked as an English teacher both in England and overseas, and more recently as a librarian in secondary schools and as a writer. She has written three simplified readers for overseas students and co-authored, with her husband, Current English Usage for Papermac and several dictionaries of etymologies for Kyle Cathie. Roger Flavell’s Master's thesis was on the nature of idiomaticity and his doctoral research on idioms and their teaching in several European languages. On taking up a post as Lecturer in Education at the Institute of Education, University of London, he travelled very widely in pursuit of his principal interests in education and training language teachers. In more recent years, he was concerned with education and international development, and with online education. He also worked as an independent educational consultant. He died in November 2005. By the same authors Dictionary o f Idioms and their Origins Dictionary o f Word Origins Dictionary o f English down the Ages DICTIONARY OF PROVERBS and their Origins L in d a and R o g er F lavell Kyle Books This edition reprinted in 2011 by Kyle Books 23 Howland Street London W IT 4AY [email protected] www.kylebooks.com First published in Great Britain in 1993 by Kyle Cathie Limited ISBN 978-1-85626-563-8 © 1993 Linda and Roger Flavell All rights reserved. -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World" -

The Portia Project: the Heiress of Belmont on Stage and Screen

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Portia Project: The Heiress of Belmont on Stage and Screen Ann Mccauley Basso University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Basso, Ann Mccauley, "The Portia Project: The Heiress of Belmont on Stage and Screen" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3000 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portia Project: The Heiress of Belmont on Stage and Screen by Ann McCauley Basso A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Sara Munson Deats, Ph.D. David Bevington, Ph.D. Denis Calandra, Ph.D. Robert Logan, Ph.D. Date of Approval March 4, 2011 Keywords: Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare, Performance, Theater History, Seana McKenna, Kelsey Brookfield, Marni Penning, Lily Rabe Copyright © 2011, Ann McCauley Basso Dedication To Giulio and Valentina, the two brightest stars in my universe. Acknowledgements I am profoundly grateful to Sara Deats, the most insightful, helpful, and utterly delightful director any dissertation writer could ever hope for. You have been my professor, my mentor, my supporter, and my friend, and you have enriched my life in countless ways. -

Curiosity / Reading List

CURIOSITY Below are excerpts from the syllabus. Students are provided with a number of different exercises that enable them to pay attention to things that they are not usually paying attention to. For example, they keep a record of their impressions involving a different sense every day for 5 days. They research the ideal creative organization or they suggest what that organization might be. They wander the campus in teams looking at all the buildings; studying architecture and the subjects taught in the different buildings. They then suggest what buildings and subjects might be combined to create a new course. They also use the founder of Soka schools, Daisaku Ikeda’s anti nuclear weapons proposal as a backdrop for developing strategies to get rid of nuclear weapons in the world. They use Edward Debono’s thinking hat technique to come up with solutions. Students are required to read a book from the list at the end of the syllabus, summarize it and write a POV re how the book relates to developing advertising strategy. At the end of the term, students work in teams to present something that they were incredibly curious about. They learn that that is what they will do for a brand if they are a strategist in an ad agency. Students leave the class far more inquisitive than when they started and they learn that curiosity is the basis of great planning. CURIOSITY FOR STRATEGISTS Required book; “The PRACTICAL POCKET GUIDE TO ACCOUNT PLANNING” By Chris Kocek Curiosity is common to human beings of all ages; from infancy to old age, and is easy to observe in many other animal species as well. -

Didacticism Meiosis Idioms Metonymy

Didacticism Idioms Charles Dickens frequently sought to educate Some of the most readers on the conditions the poor faced to raise commonly used idioms include: sympathy for those less fortunate. Such is the case in Oliver Twist: A penny for your thoughts. “So they established the rule that all poor people Add insult to injury. should have the alternative (for they would compel nobody, not they) of being starved by a gradual Back to the drawing board. process in the house, or by a quick one out of it. With this view, they contracted with the waterworks Beat around the bush. to lay on an unlimited supply of water, and with a corn-factor to supply periodically small quantities of Don’t judge a book by its cover. oatmeal, and issued three meals of thin gruel a Don’t cry over spilt milk. day, with an onion twice a week and half a roll on Sundays.” Curiosity killed the cat. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Feeling under the weather. It was a piece of cake. Make a long story short. See eye-to-eye. Taste of one’s own medicine. The last straw. Your guess is as good as mine. Metonymy Other stories include Aesop’s fables, which each contain a moral as to how one should behave. When people refer to celebrity life and culture as “Hollywood” or royalty as “the crown”, they are using metonymy (which is sometimes considered a specific form of synecdoche, or “the whole”). Meiosis Other examples include: Silicon Valley (the technology industry) Calling the period of violence in Northern Ireland The press (any media outlet) “The Troubles” or referring to the Civil War as “Our recent unpleasantness” are both examples of The Golden Arches (McDonald’s) meiosis.